Halocarpus bidwillii

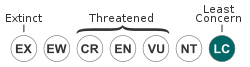

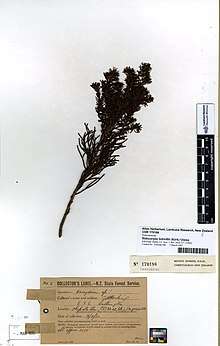

Halocarpus bidwillii, the mountain pine or bog pine, is a species of conifer in the family Podocarpaceae. It is native and endemic to New Zealand.

| Halocarpus bidwillii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Podocarpaceae |

| Genus: | Halocarpus |

| Species: | H. bidwillii |

| Binomial name | |

| Halocarpus bidwillii | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

It is an evergreen shrub favouring both bogs and dry stony ground, seldom growing to more than 3.5 m (11 ft) high. The leaves are scale-like on adult plants, 1–2 mm (0.039–0.079 in) long, arranged spirally on the shoots; young seedlings and occasional shoots on older plants have soft strap-like leaves 5–10 mm (0.20–0.39 in) and 1–1.5 mm (0.039–0.059 in) broad. The seed cones are highly modified, berry-like, with a white aril surrounding the single 2–3 mm (0.079–0.118 in) long seed.

Species Description

Although it is called a pine, the mountain pine is more like a shrub, anywhere from 2–12 feet high[3] or up to 3.5 meters high,[4] and with a short trunk that “rarely exceeds” 1 foot in diameter[3] and more commonly has a thickness up to 38 cm.[4] Bark takes on a red to brown appearance[5] and leaves have a green color when fresh, but can become brown to red when they are dried out.[3] Sometimes as the horizontal branches grow, they form roots forming a "bush" around the parent shrub which creates a vast mini-forest that looks like a huge, low tree or shrub.[4] The parent tree may die, leaving its outliers intact which are thin and red.[4] Thus from a distance, it may seem that one mountain pine is actually a whole forest of trees, perhaps explaining where the name “pine” arose to describe this short shrub.

Depending on the maturity of a mountain pine, the shrubs take on rather drastic differences in leaf appearance. In the juvenile state, leaves are linear, flat and spreading[3] much like a pine tree, while in the mature state, leathery leaves 1-2mm long[4] take on an overlapping scaled appearance, much like the scales of a fish.[3] In the flowering months of October to December[6] small male cones 3-5mm in length, take on a brown to red appearance at the end of the mountain pine’s scale like leaves,[4] and stomata are able to be seen by the naked eye as white spots.[4] Pollen particles are solitary, terminal, ca. 3–5 mm long. Appendage is adnate to base of carpel, cortex, inverted, with a drooping ovule. The fruit of mountain pine consists of a dark brown, black-brown to purple-brown seed in a fleshy, waxy white cup.[7] Seeds are 2–3 mm long, subglobose, compressed, with a white to yellow aril.[4] The aril is V-shaped under the seed. Seeds are hairless, smooth, 3.0-4.5 mm long (including arils), and take on a dark brown or dark brown to dark purple brown appearance; seeds are also typically shiny, oval oblong, and compressed.[4]

In his initial discovery of the species, Kirk identified 2 forms of mountain pine within the species that he differentiated mostly on the basis of branch shape. The alpha or erecta form of mountain pine has flat and ribbed leaves with branches being slender, while the beta or reclinata form has distinct mid-rib leaves and stout branches.[3] These two forms are very difficult however to differentiate and as such these species-specific distinctions aren’t made in current descriptions and literature of the species.

Taxonomy

Etymology

This species was named in honour of the botanist and explorer John Carne Bidwill.[8]

Geographic Distribution

Natural global range

Mountain pine is a species endemic to New Zealand.[6][3]

New Zealand range

Mountain pine are native to New Zealand and grow from Coromandel to the extreme south; as the latitude increases, they are found at lower altitudes.[9] In the North Island, mountain pine can be found in Taupo county near Rotoaira[3] and in the central volcanic plateau and Kaingaroa plains.[6] In the South Island, as the name implies, mountain pine are common in mountainous regions in Nelson, Canterbury, and Otago,[3] with some plants found as high as 4500 ft above sea level in the Canterbury alps.[3] Mountain pine can also be found on Stewart Island directly at sea level.[3][6]

Habitat Preferences

The mountain pine has a wide range of habitats, but mostly prefers montane to subalpine habitats from 39º latitude southward.[9] Within its range, the annual average temperature is 8.5℃, the coldest month average minimum temperature is -0.8℃, and the annual average precipitation is 2458 mm.[10] In the North Island, mountain pine are found exclusively in montane to alpine habitats[6] and usually between 600 –1500m elevation.[4] However, mountain pine can also thrive in low land conditions, and their presence on Stewart Island at sea level serves as an example for this.[6] Mountain pine are also hardy plants growing in a wide range of ground conditions. Mountain pine can grow in both bog environments and in dry stony ground, with mountain pine growing extremely well in the Te Anau stony ground environment[4] and just as effectively in wetland margins, frost flats, and riverbeds.[6]

Life Cycle

Like all conifers, the mountain pine life cycle is dependent on cones. Male and female flowers are found on separate trees[3] – male cones 3-5mm long are at the tips of branches [4] and female flowers grow solo or in pairs and form just below the tips of the branches.[3] From the time of seeding, male conifers will take about 2–3 years to reach maturity. When they have matured, male cones appear during the flowering season which runs from October to December,[6] but most often occurs during October and November.[4] Depending on the exact location, cone development can vary with North Island mountain pine producing cones more toward the October end of the range.[4] By the end of November, the once juvenile reddish cones take on more brown character and begin to shed pollen.[4] Around this same time, ovules grow at the tips of the branches and once fertilized by the pollen they develop a white aril at the base.[4] Seeds begin to develop in the following months up until the fruiting season, which occurs from February to June.[6] By February, green fruits mature, but do not ripen until mid to early March.[4] Once they begin to ripen, fruits ripen quickly and take on a purple to black color[4] similar to the shade of an eggplant.

The seeds themselves are only 3-4mm long and have regular grooves stretching the length of the seed.[7] Mountain pine can often be confused with closely related H. biformis, but a key difference between these 2 species’ seeds is that mountain pine seeds are typically smaller and squatter than those of H. biformis.[7]

Diet and Foraging

Mountain pine are one of the three most frost resistant types of conifers, and can typically resist frosts beyond -7 °C.[11] Similarly resilient, mountain pine are often found in poor soils.[11] True of many conifers, mountain pine actually prefer leached, low nutrient, and poorly drained soils, with many pollen diagrams showing that mountain pines thrive in infertile bogs.[11]

Although tolerant of frosts past -7 °C, mountain pines are typically found in environments with a mean annual temperature of 8.5 °C and an average minimum temperature of -0.8 °C.[12][10] Mountain pine also live in environments that average 2458mm of precipitation a year.[12][10]

Predators, Parasites, and Diseases

Thriving without true fruits, the mountain pine has few predators which are mostly herbivorous insects. Briefly, the 4 main categories of insects that prey on mountain pine are: beetles, sucking bugs, caterpillars, and mites. Weevils, a specific type of beetle, feed on all Podocarpaceae (mountain pine’s taxonomic family), and larvae thrive in any kind of decaying wood, including mountain pine.[13] More specific, scale insects, Eriococcus dacrydii, live on the stems and leaf scales of the Halocarpus species,[14] and even more specific, (Dugdale, 1996) found a species of conifer associated moth that uses the mountain pine as its host plant, appropriately named Chrysorthenches halocarpi.[15] The caterpillars of Chrysorthenches halocarpi feed on the mountain pine shoots and when too many are present, the mountain pine appears bronze and growth can be stunted.[15][16] Finally, Tuckerella flabellifera, red mites with white scales from Tasmania, live on young mountain pine plants[17] and presumably feed on the young leaves and wood.

In addition to insect predators, mountain pine also suffers from a nematode disease which is caused by the pine wood nematode. Infected trees are characterized by having yellow to brown or red to brown needles, wilting, and stopped resin secretion. In extreme cases, this disease can lead to death in which the wood takes on a blue appearance.[18] Treatments for the disease are mostly done after tree death and consist of cleaning and cutting dead wood.

Nomenclature

The epithet bidwillii is in honor of John Carne Bidwill (1815-1853) who was an Australian botanist born in England and became the first director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. However, H. bidwilli did not always identify with its current name. Kirk first discovered the species in 1877 under the name Dacrydium bidwillii,[3] a name that is still presently used at times to reference the species, and this naming was suggested by Sir Joseph Hooker.[3] It wasn’t until 1982 when C.J. Quinn proposed an alternative taxonomy for the species based on ovule morphology and orientation, that the species obtained the current scientific name of Halocarpus bidwillii.[19]

Identification

Bog pines are easily recognized when fruiting by the waxy white (very slightly yellowish) arils subtending the seed. Vegetatively compared with other species of Halocarpus, mountain pine have the growth habits of smaller multibranched shrubs to small trees, weak keel-shaped leaves, and more slender, initially quadrangular branchlets. The seeds of mountain pine are distinguished from H. biformis (with which it most often confused) by the ventral and dorsal surfaces which are usually significant longitudinally grooved (sometimes only on the ventral surface).[7]

Uses of Mountain Pine

When Kirk first described the mountain pine, he declared it to be of “little economic value” except perhaps for firewood.[3] Perhaps he was unaware at the time, but Kirk should’ve specified that mountain pine could only be used for firewood without its bark. Mountain pine is one of the few New Zealand conifers that is able to resist fire, mostly because of its thick bark, but also because of its ability to recover through basal resprouting after a fire event.[11] Other uses of the raw wood include timber production for use in buildings and railway sleepers.[20]

Another potential use for mountain pine could be for decoration. Kirk commented on the “attractive character” of mountain pine, citing its symmetrical growth, and suggested that it could become an ornamental plant.[3] Aside from decoration and perhaps firewood, no other uses of mountain pine or its products have been described to date.

Insecticidal Activity

One trait of the mountain pine that is recently receiving academic attention, but has not yet been realized by the commercial sector is the use of mountain pine plant extract as an insecticide. Extracts of mountain pine foliage have shown the presence of organic compounds like diterpenes, phyllocladane and isophyllocladene[5] and extracts of mountain pine leaves were shown to have been toxic to the codling moth, and partially toxic to the housefly.[21] In these experiments milled leaf powders of several conifers (including the mountain pine) were incorporated into the diet of several insects and the mountain pine powder had over 75% mortality rate on the codling moths tested, and 55-75% mortality on the houseflies tested.[21] Potentially toxic effects of mountain pine extract have also been studied in the germination of lettuce seeds. Foliage extracts from mountain pine significantly (p < 0.01) reduced germination when the extract came from both juvenile and adult pines, which did not differ from each other.[22] Aside from germination, both juvenile and adult pines inhibited root hair growth.[22] (Perry, 1995) hypothesized that these inhibitory effects of mountain pine might be due to allelopathic potential, since mountain pine often grow without any other vegetation below their shrubs.[22] Further research is needed before mountain pine extract becomes of any commercial value.

References

- Farjon, A. (2013). "Halocarpus bidwillii". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2013: e.T42478A2981942. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42478A2981942.en.

- "Flora of New Zealand - Taxon Profile - Halocarpus bidwillii". Flora of New Zealand. Landcare Research New Zealand. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Kirk, Thomas, 1828-1898. (1889). The forest flora of New Zealand. Govt. Printer. OCLC 223639237.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Salmon, John T. (John Tenison), 1910-1999. (1996). The native trees of New Zealand (Rev. ed.). Auckland [N.Z.]: Reed. ISBN 0790005034. OCLC 39106847.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hayman, Alan R.; Weavers, Rex T. (January 1990). "Terpenes of foliage oils fromHalocarpus bidwillii". Phytochemistry. 29 (10): 3157–3162. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(90)80178-j. ISSN 0031-9422.

- "Halocarpus bidwillii" (PDF). New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. 2013.

- Webb, C. J. (Colin James) (2001). Seeds of New Zealand gymnosperms and dicotyledons. Manuka Press. ISBN 0958329931. OCLC 50704696.

- Eagle, Audrey (2008). Eagle's complete trees and shrubs of New Zealand volume one. Wellington: Te Papa Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780909010089.

- Flora of New Zealand. Allan, H. H. (Harry Howard), 1882-1957., Moore, Lucy B., Edgar, Elizabeth., Healy, A. J. (Arthur John), 1917-2011., Webb, C. J. (Colin James), Sykes, W. R. (William Russell), 1927-. Wellington, N.Z.: Government Printer. 1961–2000. ISBN 0477010563. OCLC 80820075.CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Biffin, E.; Brodribb, T. J.; Hill, R. S.; Thomas, P.; Lowe, A. J. (22 January 2012). "Leaf evolution in Southern Hemisphere conifers tracks the angiosperm ecological radiation". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1727): 341–348. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0559. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3223667. PMID 21653584.

- McGlone, Matt S.; Richardson, Sarah J.; Burge, Olivia R.; Perry, George L. W.; Wilmshurst, Janet M. (16 November 2017). "Palynology and the Ecology of the New Zealand Conifers". Frontiers in Earth Science. 5. doi:10.3389/feart.2017.00094. ISSN 2296-6463.

- "Halocarpus bidwillii". The Gymnosperm Database. 2019.

- Kuschel, G. (2003). Nemonychidae, Belidae, Brentidae (Insecta:Coleoptera:Curculionoidea). Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. Lincoln, N.Z.: Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research. ISBN 0478093489. OCLC 52819011.

- Hoy, J.M. (1962). Eriococcidae (Homoptera: Coccoidea) of New Zealand. New Zealand: Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

- Dugdale, J. S. (January 1996). "Chrysorthenchesnew genus, conifer‐associated plutellid moths (Yponomeutoidea, Lepidoptera) in New Zealand and Australia". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 23 (1): 33–59. doi:10.1080/03014223.1996.9518064. ISSN 0301-4223.

- "Host Report With Reasons for Halocarpus bidwillii". Plant SyNZ. 2009.

- Collyer, E (1969). "Two species of Tuckerella (Acarina: Tuckerellidae) from New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Science. 12: 811–814.

- IUCN (11 January 2011). "Halocarpus bidwillii: Farjon, A.: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T42478A2981942". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011-01-11. doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2013-1.rlts.t42478a2981942.en.

- Quinn, Cj (1982). "Taxonomy of Dacrydium Sol. Ex Lamb. Emend. De Laub. (Podocarpaceae)". Australian Journal of Botany. 30 (3): 311. doi:10.1071/BT9820311. ISSN 0067-1924.

- Mabberley, D. J., author. (22 June 2017). Mabberley's plant-book : a portable dictionary of plants, their classification and uses. ISBN 9781107115026. OCLC 982092200.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Singh, Pritam; Fenemore, Peter G.; Dugdale, John S.; Russell, Graeme B. (June 1978). "The insecticidal activity of foliage from New Zealand conifers". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 6 (2): 103–106. doi:10.1016/0305-1978(78)90033-9.

- Perry, N. B.; Foster, L. M.; Jameson, P. E. (December 1995). "Effects of podocarp extracts on lettuce seed germination and seedling growth". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 33 (4): 565–568. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1995.10410629. ISSN 0028-825X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Halocarpus bidwillii. |