Groffdale Conference Mennonite Church

The Groffdale Conference Mennonite Church, also called Wenger Mennonite, is the largest Old Order Mennonite group to use horse-drawn carriages for transportation. Along with the automobile, they reject many modern conveniences, while allowing electricity in their homes and steel-wheeled tractors to till the fields. Initially concentrated in eastern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, their 10,000 members resided in eight other states as of 2008/9.

History

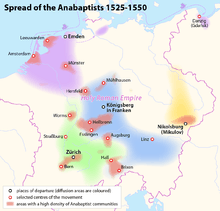

The Groffdale Conference Mennonites have their roots in the Anabaptist movement of Switzerland and Southwest Germany, including the German-speaking Alsace, that came under French rule starting in the 17th century. In the first two centuries or so this movement was known by the name Swiss Brethren but later adopted the name Mennonite.

Anabaptist beginnings

The early history of the Mennonites starts with the Anabaptists in the German and Dutch-speaking parts of central Europe. These forerunners of modern Mennonites were part of the Protestant Reformation, a broad reaction against the practices and theology of the Roman Catholic Church. Its most distinguishing feature is the rejection of infant baptism, an act that had both religious and political meaning since almost every infant born in western Europe was baptized into the Roman Catholic Church. Other significant theological views of the Mennonites developed in opposition to Roman Catholic views or to the views of other Protestant reformers such as Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli.

Some of the followers of Zwingli's Reformed church thought that requiring church membership beginning at birth was inconsistent with the New Testament. They believed that the church should be completely removed from government (the proto–free church tradition), and that individuals should join only when willing to publicly acknowledge belief in Jesus and the desire to live in accordance with his teachings. At a small meeting in Zurich on January 21, 1525, Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz, and George Blaurock, along with twelve others, baptized each other.[1]

Despite strong repressive efforts of the state churches, the movement spread slowly around western Europe, primarily along the Rhine. Officials killed many of the earliest Anabaptist leaders in an attempt to purge Europe of the new sect.

In the early days of the Anabaptist movement, Menno Simons, a Catholic priest in the Low Countries, heard of the movement and started to rethink his Catholic faith. In 1536, at the age of 40, Simons left the Roman Catholic Church. He soon became a leader within the Anabaptist movement, and was wanted by authorities for the rest of his life. His name became associated with scattered groups of nonviolent Anabaptists whom he helped to organize and consolidate.

Migration to North America

In the 18th century, about 100,000 Germans mainly from the Palatinate emigrated to Pennsylvania, where they became known collectively as the Pennsylvania Dutch. Of these immigrants, around 2,500 were Mennonites and 500 were Amish. These two groups settled mainly in southeast Pennsylvania, many of them in the Lancaster and adjacent counties.

During the Colonial period, Mennonites were distinguished from other Pennsylvania Germans in three ways:[2] their opposition to the American Revolutionary War, which other German settlers participated in on both sides; resistance to public education; and disapproval of religious revivalism. Contributions of Mennonites during this period include the idea of separation of church and state, and opposition to slavery.

From 1812 to 1860, another wave of Mennonite immigrants from Europe settled farther west in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Missouri. These Mennonites, along with another wave of Amish, came from Switzerland, Southwest Germany and the Alsace-Lorraine area.

Old Order Movement

The Groffdale Conference has its roots in the Old Order divisions, that occurred in Indiana in 1872, and in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1893, over the question of English language preaching, Sunday Schools and other questions. The trigger for the split in Lancaster County was a quarrel about a pulpit, that was to be installed in church instead of the traditional preacher's table.[3]

The modernizing trends that changed the form of religious practice were pushed among the Mennonites especially by two men: John F. Funk and John S. Coffman. The Groffdale Conference Mennonites still call modernized Mennonites Funkeleit, that is Funk people.[4] The traditional minded people left the old conferences to form new ones, not the modernizers.[5][6]

The emergence of the Groffdale Conference

The Groffdale Conference arose in 1927 at the conclusion of a seventeen-year disagreement within the Weaverland Old Order Mennonite Conference, over use of the automobile.[7] Five hundred of the more traditional members of the Weaverland conference, about half of the congregation, formed this group in order to retain horse-drawn transportation. The name of the conference comes from the Groffdale churchhouse where Joseph O. Wenger led the first worship services.[8]

Further history

The John W. Martin Mennonites, a group of Old Order Mennonites from Indiana, merged with the Groffdale Conference in 1973.[9]

In 1974 a new settlement in Yates County, New York, was started. It grew quickly and steadily and with a population of more than 3,000 in 2015 it was almost as large as the Lancaster County settlement.[10]

The Wenger Mennonites ("Joe Wengers", "Wengerleit", "Fuhre Mennischte") or Groffdale Conference Mennonites experienced several smaller splits during their history:

- 1942: Dozens of members refrained from communion because of the CPS issue, later several more conservative Old Order groups were founded or joined by these people: directly founded: Reidenbach Mennonites, joined: Phares Stauffer Pike Mennonites, then Aaron Martin Pike Mennonites and further groups in Snyder County-

- 1990s: Electricity issues and permission for the ministry as for the laity before also created a separate group: John Martin (Groffdale Conference) Mennonites. This group never grew much.

- 1993: Steel Wheel issues also were almost creating a split around 1993 when the rubber belt issue was at its height, the steel wheel issue also played oftentimes a role in conflicts with the state(see Mitchell Couty vs. Zimmerman).

- 2000s: After decades of trying to establish a well-grounded and growing(which never happened) ultraconservative Groffdale Conference Mennonite subgroup(moving therefore from counties in Penna to Kentucky), Jacob Oberholtzer after becoming finally bishop in Casey County split off. This group is located close to Spencer, Tennessee currently after moving away from Casey County.

All these former splits were smaller ones, in 2019 a big one happened:

- 2019: The split resulted from the computer issue in 2019, while several other reasons played also a role in it. This effected Missouri, Kentucky, New York and Indiana, where bishops, preachers and deacons left the Wenger Mennonites with a big amount of laity, but still minority and formed a loosely connected Midwest Conference. In 2016 already some problems were made public when a bishop of Missouri added some pages to the annual printing of Calendars and later this edition had to be destroyed and a second printing was distributed to the laity (of course without these pages).Some of the conservative split-offs before and even some Stauffer Mennonite current split-offs (Arthur Martin movement) work together with the new formed Midwest Conference.

Belief and practice

The black carriages of the Wenger Mennonites distinguish them from the Amish in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, who use gray ones.[11] They are mainly rural people, who work small farms. Initially concentrated in eastern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, they resided in eight other states as of 2002.[12]

Church members use modern self-propelled farm machinery and lawn mowers that have been refitted with steel wheels. Starting in the 1970s, some farmers used rubber belts and blocks to give wheels more traction, provide a smoother ride and reduce damage to public roads. This practice caused considerable debate within the community, which was resolved in 1999 with a compromise that allows limited use of rubber in the structure of steel wheels.[13] Hard rubber or pneumatic tires are allowed on bicycles and machinery not requiring a driver, such as walk-behind equipment and wagons. Use of steel wheels ensures tractors are not used as a substitute for automobiles to run errands or to make more extensive trips than are convenient with horse-drawn carriages. The steel wheel rule prevents large agricultural operations, reinforcing an emphasis on small farms that provide manual labor for all of the family members.

The German language is used for Bible reading and singing in worship services and Pennsylvania German is used in worship services for preaching and is spoken at home and with other Old Orders.[14] They meet in plain church buildings to worship, but do not have Sunday schools. Practicing nonresistance like other traditional Mennonite groups, during World War II they advised young men not qualifying for a farm deferment to accept jail terms instead of Civilian Public Service, the alternate used by other Anabaptist conscientious objectors.[12]

Demographics

The group consisted of about 500 members in their beginning in 1927 and grew to about 1,200 members in 1954.[15] In 1957 there were 1,450 members.[16] In 1992 there was an estimated membership of 5,464.[17]

As of 2002, the conference has grown to 49 congregations with 8,542 members and a total population of 17,775 with 20% and 66% of population below 5 years and below 21 years respectively.[18] The population has an annual growth rate of 3.7 percent, doubling about every 19 years.[11] In 2008/9 membership was 10,000 in 50 congregations.[19]

In 2015 the group had a total population of 22,305 people of which 9,620 lived in Pennsylvania, 995 in Indiana, 600 in Iowa, 1,112 in Kentucky, 300 in Michigan, 1,545 in Missouri, 3,934 in New York, 1,805 in Ohio and 2,395 in Wisconsin.[9][20]

The Groffdale Conference Mennonites have a growth rate of 3.7 percent a year which is comparable to the growth rate of the Old Order Amish.[11]

See also

References

- Strasser, Rolf Christoph (2006). "Die Zürcher Täufer 1525" [The Zurich Anabaptists 1525] (PDF) (in German). EFB Verlag Wetzikon. p. 30. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- Samuel Floyd Pannabecker: Open Doors: A History of the General Conference Mennonite Church, Newton, Kansas, 1975, page 12.

- Stephen Scott: An Introduction to Old Order: and Conservative Mennonite Groups, Intercourse, PA 1996, pages 20-24.

- Donald B. Kraybill and James P. Hurd: Horse-and-Buggy Mennonites - Hoofbeats of Humility in a Postmodern World, University Park, PA, 2006, page 24.

- Stephen Scott (1996). An Introduction to Old Order: and Conservative Mennonite Groups. Good Books, Intercourse, PA. pp. 12–27.

- Old Order Mennonites at Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online.

- Donald B. Kraybill and James P. Hurd: Horse-and-Buggy Mennonites - Hoofbeats of Humility in a Postmodern World, University Park, PA, 2006, pages 63-74.

- Donald B. Kraybill and James P. Hurd: Horse-and-Buggy Mennonites - Hoofbeats of Humility in a Postmodern World, University Park, PA, 2006, page 21.

- Donald B. Kraybill (2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hurtterites and Mennonites. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 157.

- Reid, Judson (2019-11-16). "Old Order Mennonites in New York: Cultural and Agricultural Growth". Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies. 3 (2): 212–221. ISSN 2471-6383.

- Donald B. Kraybill and James P. Hurd: Horse-and-Buggy Mennonites - Hoofbeats of Humility in a Postmodern World, University Park, PA, 2006, pages 2-3.

- Landis 1959.

- Donald B. Kraybill and James P. Hurd: Horse-and-Buggy Mennonites - Hoofbeats of Humility in a Postmodern World, University Park, PA, 2006, Chapter 3, Mobility and Identity, pages 63-89.

- Groffdale Old Order Mennonite Conference at Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online.

- Landis 1957.

- Old Order Mennonites at Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online.

- Stephen Scott: An Introduction to Old Order: and Conservative Mennonite Groups, Intercourse, PA 1996, page 30.

- Kraybill, Donald B; Hurd, James P. (2006). Horse-and-Buggy Mennonites Hoofbeats of Humility in a Postmodern World. University Park, PA. p. 3.

- Donald B. Kraybill (2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hurtterites and Mennonites. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 258.

- Simon J. Bronner and Joshua R. Brown (edit.): Pennsylvania Germans: An Interpretive Encyclopedia, Baltimore, 2017, pages 126-7.

Literature

- Donald B. Kraybill and James P. Hurd: Horse-and-Buggy Mennonites - Hoofbeats of Humility in a Postmodern World, University Park, PA, 2006. (This 362-page book about the Groffdale Conference Mennonites is the most in depth study of any Old Order Mennonite group)

- Stephen Scott: An Introduction to Old Order and Conservative Mennonite Groups. Intercourse, PA 1996.

- Donald B. Kraybill and Carl Bowman: On the Backroad to Heaven: Old Order Hutterites, Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren. Baltimore 2001.

- Thomas J. Meyers and Steven M. Nolt: An Amish patchwork: Indiana's Old Orders in the Modern World. Bloomington, IN et al. 2005.

- Donald B. Kraybill: Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites. Baltimore 2010.

- Donald B. Kraybill and C. Nelson Hostetter: Anabaptist World USA. Scottdale, PA and Waterloo, Ontario 2001.