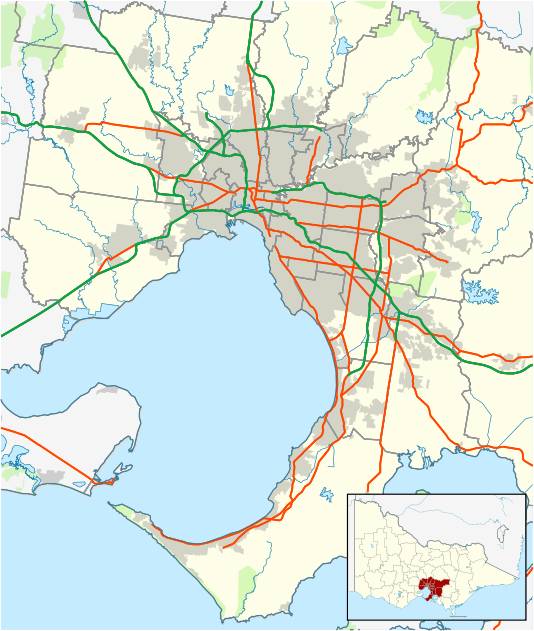

Greensborough, Victoria

Greensborough is a suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 17 km north-east from Melbourne's Central Business District.[2] Its local government areas are the City of Banyule and the Shire of Nillumbik. At the 2016 Census, Greensborough had a population of 20,821.[1]

| Greensborough Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Aerial view from the north, Greensborough Bypass just in foreground, Greensborough Plaza in centre of image, and Greensborough railway station to left. | |||||||||||||||

Greensborough | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37.686°S 145.117°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 20,821 (2016)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,843/km2 (4,772/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3088 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 11.3 km2 (4.4 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 17 km (11 mi) from Melbourne CBD | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | |||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Jagajaga | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The suburb was named after settler Edward Bernard Green, who was also the district mail contractor.[3] Formerly it was known as Keelbundoora.[4]

Aboriginal Heritage

The Wurundjeri willam people from the Kulin nation are the traditional owners of the land north-east of Melbourne, including the area which is the Banyule City Council.[5] They belong to the Woiworung speaking people and had connections with other clans and lands.[5] The Wurundjeri willam were divided into three smaller groups.[6] The group present around the Yarra, that includes Banyule were called Bebejan's Mob.[6] This area was described as 'tract at Heidelberg, up Yarra to Mt. Baw Baw, about Yering'[7]

Woiworung clans were based on the Yarra River and its catchments.[5] The Kulin nation was divided into clans from south-central Victoria and six language groups, including the Woiworung.[5]

The Wurundjeri willam, like all Kulin, were multilingual.[5] It was considered respectful to speak the hosts language when visiting allied clans from south-central Victoria.[5]

The Kulin clans were divided in two subdivisons : one group the Waa (crow) moiety (group defined according to spiritual or totemic association), the other group Bunjil (eagle hawk) moiety.[8] Waa was the Wurundjeri william moiety.[5]

It was important that when women and men came of age that they marry from the opposite moiety. That is, both men and women from the Bunjil moiety had to marry a partner from the Waa moiety.[5] This law ensured intermarriage between different clans. Relationships of this kind in the entire Kulin nation, connected families and allowed the first nations peoples to move through different clan lands when needed.[8]

The clans were connected in a variety of ways through language, marriage and religious beliefs.[8] Due to white settlement in the mid 1830s, the Kulin way of life was disrupted quickly and dramatically, there is little documentation about the Wurundjeri willam spiritual life.[8] We can only assume that it was rich and complex.[8]

Significant Historical Figures

Here is a small list of significant historical figures in the Wurundjeri willam history. These Indigenous clans men had all witnessed or participated in the signing of Batman's Treaty.

Bebejan

Bebejan, was a Ngurungaeta (headman), during the time the Europeans invaded Kulin nation. In June 1835, he was one of the eight Wurundjeri willam who put their mark on the Batman Treaty.[8] His son was William Barak.

Billibellarg

Billibellarg, was the head of his clan of one of the Wurundjeri willam peoples of the Woi worung language.[8] He was one of the most influential clan heads of the Eastern Kulin in the 1840s.[8] Billibellarg was a custodian of the Mount William stone axe quarry. He is the brother of Bebejan and his name is listed on the Batman Treaty.[8]

William Barak

Beruk, the son of Bebejan spent his childhood learning the heritage of his ancestors.[5] In 1835, twelve year old Beruk, watched the signing of John Batman's Treaty with his father and uncle (Billibellarg).[5] When he was older, he changed his name to William Barak, and became, arguably the most significant historical figure to pursue a better life for his people.[5] One of the last clans head of the Wurundjeri willam, he established the settlement of Corranderrk where many Woi Wurrung lived until the 1920s.[6] His petitions to parliament won support from settlers, journalists, church leaders and politicians.[5] William Barak was instrumental in preserving the Kulin nation culture and documented his knowledge with anthropologist Alfred Howitt.[5]

European Settlement

There is much debate over the precise location of the signing of the Batman's Treaty. Some say the settlement of the Port Phillip District is linked with the story of Greensborough.[9] That John Batman traveled to the East side of the Plenty River to negotiate the Treaty and that the location was within or close to Banyule.[10] However, it is difficult to follow Batman's itinerary and his description is too general,[6] there are possibly other places such as Merri Creek or Darebin Creek.[5]

John Batman made his treaty claiming 600,000 acres of Kulin land for a few trinkets and blankets.[9] It is inconceivable to the Kulin that they would sell off their land.[5] The land and the Kulin are deeply connected.[8] They believed they were participating in a Tanderrum ceremony.[5] A ceremony asking for temporary access to the land.[6] There is no official status in John Batman's attempt to take lands in Victoria for gifts and trinkets.[11]

Within a year of Batman's arrival there were 26,500 sheep grazing and the village of Bearbass (later to be renamed Melbourne) consisted of three weatherboard, two slate and eight turf huts.[9]

The Governor of New South Wales received instructions to disallow Batman's Treaty with the Wurundjeri willam and to remove all trespassing settlers.[9] This was unsuccessful. The Port Phillip District was surveyed, and on the 12 September 1838, the first action of Kulin land was sold in Sydney.[9]

The decimation and eventual destruction of the Wurundjeri willam came with the founding of Melbourne in 1835.[6] In less than 30 years of the settlement of Melbourne, the First Peoples population had been severely reduced due to the effects of disease, alcohol and conflicts over access to land and livestock.[6]

By 1860 the surviving Wurundjeri william were take away from the Melbourne area and forced to live on mission stations throughout the colony.[6]

The treatment of the Indigenous population by the colonial government will remain contentious. European settlement is not legitimate because the British administrators refused to acknowledge the traditional owners.[11] There was no negotiation for appropriate treaties or any compensation for the settlement of the Kulin nation by European settlers.[11] This refusal of recognition of the Wurundjeri willam as traditional owners gave little opportunity to observe and record the culture and lifestyle of the local people.[6] Therefore, the rapid demise of the peoples traditional lifestyle following European settlement would soon be lost forever.

In Banyule the discovery of Aboriginal archaeological sites adds a historical dimension to the municipality.[6] These sites are significant compared to other municipalities because Banyule has had minimal urban development.[6] Some other local governments outside Banyule may lack field survey and archaeological investigation.[6] Banyule's Aboriginal archaeology represents part of the history of the Wurundjeri willam and therefore has several important roles. These include:

- providing a material link between the Wurundjeri willam's past use of land and its resources and the present day Aboriginal community, particularly the descendants of the Wurundjeri willam.[6]

- providing a source of scientific data that allows for the reconstruction of the Wurundjeri willam life-ways prior to European settlement.[6]

- presenting a means of educating the general public on the cultural history of the Wurundjeri willam as a group of Melbourne's indigenous people and indeed on the early history of white settlement and the development of contemporary political and social values.[6]

Today, the Aboriginal custodians of Banyule and the Kulin Nations preserve their powerful cultural heritage through the Wurundjeri Tribe Land Compensation and Cultural Heritage Council Incorporated.

History

In 1838, Henry Smythe, a Crown grantee, purchased 259 hectares for 544 pounds, from John Alison.[10] The boundaries of this land included Gold Street in the North, Macorna Street in the West, Grimshaw Street in the South and Plenty River in the East.[10] In 1841 he sold this land for 1600 pounds to Edward Bernard Green and it was from Green that Greensborough derived its name.[10]

The township was established in the late 1850s, with the Post Office opening on 17 July 1858.[12] In 1842, Charteris Lieutenant, Robert Whatmough started his own orchard. Whatmough's knowledge of botany was extensive and had published a comprehensive book on Botany after arriving in Australia.[13] Trees can still be found growing in Greensborough, along the Plenty River Trail. By 1871, Greensborough had a population of 167 and by 1933 had grown to 940.[14]

In 1845 a small private school was established.[10] The school was a slab hut with a large fireplace that filled the end wall.[9] Mr. Purcell, the teacher charged two shillings, per week for each of his twenty pupils.[9] The building was destroyed by fire and another school did not re-open until 1854.[10] There is very little information about the school or the teaching methods of Mr. Purcell.

Greensborough Hotel

In 1864, the Greensborough Hotel, formally known as the Farmers Arms Hotel, was built by Englishman James Iredale. It served as a stopping point for travelers on their way to the goldfields further north. By law, a lit lantern was required as a sign of welcome to those needing a well earned rest or to refresh their horses. [15]It was later demolished and rebuilt in 1925, by then owner Denis Monahan to make way for the newer version.[16] Greensborough Hotel, by architects Sydney Smith, Ogg and Serpell, 349 Collins Street, Melbourne, has been well thought out, and the three sources of income - the bar, the dining room and the residential section, although all under easy supervision from the office, are kept absolutely distinct, so that visitors to any of these three sections are separate.[17] Greensborough Hotel is the second hotel to occupy this site and represents a continuation of use spanning close to 150 years.[18] The Greensborough Hotel is aesthetically significant as an unusual example of the inter-War Spanish Mission style hotel in the suburb of Greensborough.[18] It is one of the few early Twentieth Century buildings remaining in the area and has become an attractive landmark in the commercial centre of Greensborough. Greensborough Hotel is located on the corner of Main Street and The Circuit, Greensborough.

A telegraph line connecting Greensborough and Diamond Creek with Heidelberg was completed in 1888.[10] From 27 July 1888 a telephone link across the line was added so that telegrams could be sent or received by telephone.[10]

During the 1880s and 1890s Diamond Valley became popular with excursionists from inner Melbourne.[10] Tourism increased with the advent of the railway line in the twentieth century.[10] Greensborough was noted for its fishing (cod, perch, blackfish and eels). Another leisure pursuit that was taken up by visitors was shooting. Rabbit and hares were plentiful and the hotel provided accommodation for weekend visitors.[10]

The Diamond Valley Football Association was formed 1922 at Diamond Creek and initially consisted of teams from Kangaroo Ground, Eltham, Diamond Creek, Templestowe, Greensborough, and Warrandyte.[10]

Geography

Greensborough borders the beginning of the Green Wedge, an area of bush land that runs northward into Eltham and Diamond Creek. The Plenty River, a tributary of the Yarra River, runs through Greensborough, joining the Yarra at Templestowe.

Amenities

One of the major buildings in Greensborough is the Lend Lease owned Greensborough Plaza. Greensborough Plaza is a major regional shopping centre commonly regarded as the main retail hub servicing Melbourne's north-eastern suburbs. It was built in 1976 and has since undergone numerous renovations which have changed it from a small, basic shopping centre into a multi-level facility. The shopping centre's major tenants include Coles, Kmart, Target, Aldi and JB Hi-Fi as well as a Hoyts Cinema complex.

The Plaza is not the only shopping option as the adjacent Main Street offers many shops of different varieties.

In 2009, the Greensborough Town Centre was set to receive a major upgrade although most of the improvements were delayed or cancelled due to the global financial crisis. However, in the prevailing years a new state-of-the-art aquatic centre, WaterMarc, has been built alongside an upgraded multi-level car park and Greensborough Walk, a new pedestrian promenade connecting Main Street with Watermarc. In 2017, the Banyule City Council moved their main offices to Greensborough from Ivanhoe[19] as part of the wider "One Flintoff" project which included new offices and community facilities that were built above WaterMarc.[20] However, due to historical considerations council meetings continue to be held at the Old Heidelberg Town Hall in Ivanhoe.[21]

The Nillumbik Shire offices are also located in Greensborough at the site of the former Diamond Valley offices, next to the Diamond Valley library.

Diamond Valley Library, Civic Drive, Greensborough is operated by Yarra Plenty Regional Library

Transport

Greensborough and the surrounding suburbs is serviced by a network of roads including the Greensborough Highway, which bypasses the town centre and connects to the Metropolitan Ring Road. The main street is Main Street which runs into Diamond Creek Road, while other main arterials include Para Road which runs south and Grimshaw Street which runs west.

Greensborough railway station is the only passenger train station in the suburb, located on the Hurstbridge railway line. The suburb serves as a major hub for bus services for the surrounding area, with most services departing from the Main Street terminal. To this end, pedestrian links between the station and Main Street were due to be upgraded in between 2010 and 2015 as part of the Greensborough Project development to improve public transport connectivity. The(se) link(s) have not yet been re-proposed by either local, state or federal governments.

Education

The first government primary school opened in 1875.[14] Greensborough College is a high school with over approximately 518 students, located between Greensborough and Watsonia. Greensborough is also home to several primary schools including Greensborough Primary School, established in 1878, St Mary's Catholic Primary School, St Thomas the Apostle Catholic Primary School, Greenhills Primary School, Watsonia Heights Primary School and Apollo Parkways Primary School.

The Greensborough Melbourne Polytechnic campus reopened in 2017 aided by a $10 million state government investment after initially closing in 2013.[22]

Sport and recreation

Greensborough has an AFL team playing in the Northern Football League. Diamond Valley United Soccer Club also play at Partington's Flat and currently compete in Victorian State League Division 2.

Greensborough has a polyurethane athletic track at Willinda Park, which is the home of the Diamond Valley Little Athletics Centre, the largest Little Athletics Centre in Victoria with over 750 athletes, the Diamond Valley Athletic Club and the Ivanhoe Harriers.

The DVE Aquatic Club also operates out of Watermarc.

Parks, gardens and reserves

Andrew Yandell Reserve, Greensborough is located at 37 St. Helena Road, Greensborough, Victoria. The site occupies over six hectares of indigenous bushland maintained by the City of Banyule.[23] The Yandell Habitat Reserve is of local historic, scientific, social, and aesthetic significance to the City of Banyule.

See also

- Shire of Diamond Valley - Greensborough was previously within this local government area.

- City of Banyule - Greensborough is currently within this local government area.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Greensborough (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Postcode for Greensborough, Victoria (near Melbourne) - Postcodes Australia".

- "Prahran Mechanics' Institute – Greensborough, Victoria, Australia – History". pmi.net.au. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- "Darebin Parklands – History". dcmc.org.au. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- Sutherland, Phillippa. "Heartland of the Wurundjeri willam". Banyule Council Aboriginal Heritage.

- Marshall, Brendan (1999). Aboriginal Heritage Study: Banyule City Council. https://www.banyule.vic.gov.au/Services/Planning/Heritage/Aboriginal-Heritage: Austral Heritage Consultants. pp. 10, 14, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39.

- Barwick, Diane E. (January 2011). "Mapping the past: an atlas of Victorian clans 1835–1904". Aboriginal History. 8. doi:10.22459/ah.08.2011.08. ISSN 0314-8769.

- Presland, Gary. (2010). First people : the Eastern Kulin of Melbourne, Port Phillip and Central Victoria. Melbourne, Vic.: Museum Victoria Pub. ISBN 9780980619072. OCLC 651616247.

- Greensborough State School. (1954). Centenary of education in Greensborough, 1854-1954. [The School]. OCLC 220829503.

- Edwards, Dianne H. (Dianne Helen), 1949- (1979). The Diamond Valley story. Diamond Valley Shire (Vic.). Greensborough, Vic.: Shire of Diamond Valley. ISBN 0959542205. OCLC 8280660.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mansell, Michael, 1951- (2016). Treaty and statehood : Aboriginal self-determination. Sydney. ISBN 9781760020835. OCLC 961474048.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- "Newspaper clipping - A True Son of The Pioneers - Victorian Collections". victoriancollections.net.au. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Greensborough | Victorian Places". www.victorianplaces.com.au. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- Shanahan, Brittany (7 April 2017). "Historic photographs of Greensborough's booming heart". Leader Community News North – via Herald-Sun.

- "A walk down valley's memory lane". www.heraldsun.com.au. 7 April 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Greensborough Hotel, Greensborough, Victoria". Hotels and their making: what Australia lacks. Federation Builders' Association of Australia. 38: 60. 12 July 1926 – via Trove.

- "Greensborough Hotel". Victorian Heritage Database. 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010. Retrieved https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/124140.

|first=missing|last=(help); Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - "New civic office opens". www.banyule.vic.gov.au. 10 April 2017.

- "The Greensborough Project". www.banyule.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Banyule Council has finally moved into its 'Taj Mahal' head office". www.banyule.vic.gov.au. 25 April 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Melbourne Polytechnic Greensborough Campus Unveiled". www.melbournepolytechnic.edu.au. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Andrew Yandell Reserve". www.banyule.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 23 May 2019.