Gospel of James

The Gospel of James, also known as the Protoevangelium of James, and the Infancy Gospel of James, is an apocryphal gospel probably written around the year AD 145, which expands backward in time the infancy stories contained in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, and presents a narrative concerning the birth and upbringing of Mary herself. It is the oldest source to assert the virginity of Mary not only prior to, but during (and after) the birth of Jesus.[2] The ancient manuscripts that preserve the book have different titles, including "The Birth of Mary", "The Story of the Birth of Saint Mary, Mother of God," and "The Birth of Mary; The Revelation of James."[3] It is also referred to as "Genesis of Mary".[4]

| Gospel of James | |

|---|---|

| Date | ~140-170 AD |

| Attribution | James, brother of Jesus |

| Location | Jerusalem, likely within the province of Roman Palestine |

| Sources | Gospel of Matthew, Gospel of Mark, Gospel of Luke, Gospel of John,[1] Septuagint, extracanonical traditions |

| Manuscripts | various, mostly Byzantine |

| Audience | Jewish Christian |

| Theme | Virginity of Mary, Betrothal of Mary and Joseph, and the birth of Jesus |

Authorship and date

The protoevangelium presents itself as written by a source of moral and ecclesiastical authority, ending with the declaration: "I, James, wrote this history in Jerusalem."[5] The purported author is thus James, the brother of Jesus, who held considerable influence within the early Christian community. However, textual scholarship has indicated that the text is a work of pseudepigrapha, a common literary style to this period. It was likely composed some time in the mid-second century.[6]

Although earlier scholars claimed the author(s) had a Jewish background (due to references to the duties of the Jewish priestly office, various temple rituals and protocols, and Jewish legal practices common to the Second Temple period),[7] in fact the author(s) appear to have been poorly informed about Jewish practices (e.g. "Joachim is forbidden to offer his gifts first because of childlessness; Mary is taken to be a ward of the Temple; Joseph plans to go from Bethlehem to Judea"; further, the "water of jealousy" was not administered to men and Simeon was not a high‐priest in the Bible).[8] Many scholars have debated the issue and the text's relation to Judaism.[9]

The style of the language that has been employed supports the argument that the text dates from the second century. The author describes various Jewish social and ecclesiastical activities that are heavily contested by scholars.[10]

The consensus is that it was composed sometime in the middle of the second century. The first mention of it is in the early third century by Origen of Alexandria, who says the text, like that of a Gospel of Peter, was of dubious, recent appearance and shared with that book the claim that the "brethren of the Lord" were sons of Joseph by a former wife.[11]

Although a number of church councils condemned it as an inauthentic writing of the New Testament, this did little to diminish its popularity. Pope Innocent I condemned this Gospel of James in his third epistle ad Exuperium in 405 AD, and the so-called Gelasian Decree also excluded it as canonical around 500 AD.[12] Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologiae, rejects the Protevangelium of James teaching that midwives were present at Christ's birth, and invokes Jerome as contending that the words of the canonical gospels show that Mary was both mother and midwife, that she wrapped up the child with swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger. And thus concludes, "These words prove the falseness of the apocryphal ravings."[13]

It does appear to have helped inform the Islamic tradition of the lives of Mary and Christ, and appears to directly relate to the references made to her piety in the pages of the Quran.[14][15]

Literary genre

The Protoevangelium of James is one of several surviving Infancy Gospels within early Christian literature. The majority scholarly consensus is that it was composed by the early church to expand upon the canonical gospels in more extensive way, granting more details about the early life of Christ.[16] The term 'Protoevangelium' stems from the Koine Greek cognate, meaning 'prior to the gospel', 'pre-gospel' or 'infancy gospel'. It is a title attributed to the text, but not explicitly used by the author(s).

Such a work was intended to be "apologetic, doctrinal, or simply to satisfy one's curiosity".[17] The literary genre that these works represent shows stylistic features that suggest dates in the 2nd century and later. Other infancy gospels in this tradition include The Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (based on the Protevangelium of James and on the Infancy Gospel of Thomas), and the so-called Arabic Infancy Gospel, all of which were regarded by the Church as apocryphal.

Manuscript tradition

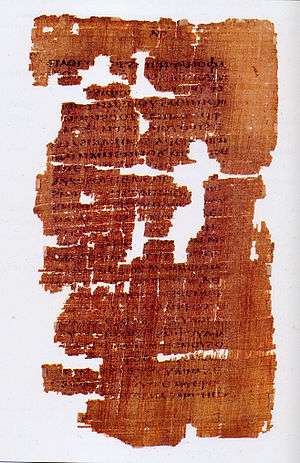

Some indication of the popularity of the Infancy Gospel of James may be drawn from the fact that over 150 Greek manuscripts containing it have survived. The Gospel of James was translated into Syriac, Ethiopian, Coptic, Georgian, Old Church Slavonic, Armenian, Arabic, Gaelic, and Vulgar Latin. Though no early Latin versions are known, it was relegated to the apocrypha in the Gelasian Decretal, so it must have been known in the Western church before the fifth century, though the vast majority of the manuscripts come from the 10th century or later. The earliest known manuscript of the text, a papyrus dating to the third or early fourth century, was found in 1958; it is kept in the Bodmer Library, Geneva (Papyrus Bodmer 5). Of the surviving Greek manuscripts, the fullest text is a 10th-century codex in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris (Paris 1454),

Content of the text

The Protoevangelium of James is divided into twenty-four chapters, broken down into three sections:

- The first contains the story of the miraculous birth of Mary to Anna, who is infertile, and Mary's childhood and dedication to the temple.

- The second starts when she is twelve years old, and through the direction of an angel, Joseph is selected to become her husband.

- The third relates the Nativity of Jesus, with the visit of midwives, hiding of Jesus from Herod the Great in a feeding trough and the parallel hiding in the hills of John the Baptist and his mother (Elizabeth) from Herod the Great.

One of the work's high points is the Lament of Anna. A primary theme is the work and grace of God in Mary's life, Mary's personal purity, and her perpetual virginity before, during and after the birth of Jesus, as confirmed by the midwife after she gave birth, and tested by Salome who is perhaps intended to be Salome, later the disciple of Jesus who is mentioned in the Gospel of Mark as being one of the women at the crucifixion. The check of Mary's virginity by Salome is the first written record of a gynecological examination. In theme with Mary's perpetual virginity, Salome's hand catches on fire as punishment for attempting to touch the Virgin Mary.[18]

This is also the earliest text that explicitly claims that Joseph was a widower, with children, at the time that Mary is entrusted to his care. This feature is mentioned in the text of Origen, who adduces it to demonstrate that the 'brethren of the Lord' were sons of Joseph by a former wife.[11]

Among further traditions not present in the four canonical gospels are the birth of Jesus in a cave, the martyrdom of John the Baptist's father Zechariah during the Massacre of the Innocents and Joseph's being elderly when Jesus was born. The Nativity reported as taking place in a cave remained in the popular imagination; many Early Renaissance Sienese and Florentine paintings of the Nativity continued to show such a setting, which is practically universal in Byzantine, Greek and Russian icons of the Nativity. The Gospel also describes the narrative of Mary’s early childhood in the holiest part of the temple, which was later also mentioned in the Qur’an.[19] The Quran does not, specifically, say that Mary lived and grew up in a temple as the word miḥ'rāb in Surah 3:36 in its literal meaning refers to a private prayer chamber[20] or a private chamber in general.[21] Outside of this Surah there is no hint or any mention of a temple in which Mary supposedly grew up.

See also

- Castelseprio - early fresco depiction of the Trial by water

- History of Joseph the Carpenter

- New Testament apocrypha

- Pseudepigraphy

- Textual criticism

- Meeting of Joachim and Anne at the Golden Gate

References

- Porter, J. R. (2010). The Lost Bible. New York: Metro Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4351-4169-8.

- Gambero, Luigi (11 June 1999). Mary and the Fathers of the Church: The Blessed Virgin Mary in Patristic Thought. Ignatius Press. ISBN 9780898706864 – via Google Books.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2 October 2003). Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It into the New Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743681 – via Internet Archive.

lost scriptures.

- Brent Nongbri, The Archaeology of Early Christian Manuscripts, Ancient Near East Today (ANET), American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR), April 2019, Vol. VII, No. 4. Accessed 18 April 2019

- Trowbridge, Geoff. "The Infancy Gospel of James". maplenet.net.

- Barriger, Lawrence. "American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese of North America - The Protoevangelium of St. James". www.ACROD.org. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Lowe, Malcolm (1981). "Ἰουδαῖοι of the Apocrypha: A Fresh Approach to the Gospels of James, Pseudo-Thomas, Peter and Nicodemus". Novum Testamentum. 23 (1): 56–90. doi:10.2307/1560751. JSTOR 1560751.

- The Apocryphal New Testament: A collection of apocryphal Christian literature in an English translation. Elliott, James Keith. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1993. chap. 5. ISBN 0198261829. OCLC 26975279.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Vuong, Lily C. (25 June 2019). The Protevangelium of James. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 21–28. ISBN 9781532656170.

- Horner, T.J. (Fall 2004). "Jewish Aspects of the Protoevangelium of James". Journal of Early Christian Studies. Johns Hopkins University Press. 12 (3): 313–335. doi:10.1353/earl.2004.0041.

- Origen of Alexandria. "The Brethren of Jesus". Ante-Nicene Fathers. Origen's Commentary on Matthew 10.17. IX. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

But some say, basing it on a tradition in the Gospel according to Peter, as it is entitled, or The Book of James, that the brethren of Jesus were sons of Joseph by a former wife, whom he married before Mary. Now those who say so wish to preserve the honour of Mary in virginity to the end, so that that body of hers which was appointed to minister to the Word which said, "The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee and the power of the Most High shall overshadow thee," might not know intercourse with a man after that the Holy Ghost came into her and the power from on high overshadowed her.

- Betsworth, Sharon (2014). Children in early Christian literature: Children as characters, metaphors, and types in early ... T & T Clark. p. 169. ISBN 978-0567235466.

- Aquinas, Thomas. "Summa Theologiae". New Advent. Kevin Knight. Third Part. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Horn, Cornelia M. (2006). "Intersections: The Reception History of the Protoevangelium of James in Sources from the Christian East and in the Qu'rān". Apocrypha. 17: 113–150. doi:10.1484/J.APOCRA.2.302050.

- Horn, Cornelia B. (2007). "Mary between Bible and Qur'an: Soundings into the transmission and reception history of the Protoevangelium of James on the basis of selected literary sources in Coptic and Copto-Arabic and of art-historical evidence pertaining to Egypt". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. 18 (4): 509–538. doi:10.1080/09596410701577332.

- http://www.maplenet.net/~trowbridge/infjames.htm

- "Toschi, O.S.J., Larry M. Toschi."St. Joseph in Apocrypha", Oblates of St. Joseph". Osjusa.org. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- 1978-, Vuong, Lily C. (2013-11-19). Gender and purity in the Protevangelium of James. Tübingen, Germany. ISBN 9783161523373. OCLC 864435188.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "The smashers of Mary's images are acting more against statues than against her". The Economist. 30 Nov 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "Quran 3:37 "mih'rab" translated as (prayer) chamber".

- "Quran translation by Yusuf Ali".

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Early Christian Writings website: Infancy Gospel of James

- St. Joseph in Apocrypha, from "Oblates of St. Joseph".

- The Protoevangelium of James