Dragon robe

Dragon robes (袞龍袍, pinyin: gǔn lóng páo, hangul: 곤룡포) were the everyday dress of the emperors or kings of China (since the Tang dynasty), Korea (Goryeo and Joseon dynasties), Vietnam (Nguyễn dynasty) and the Ryukyu Kingdom.

China

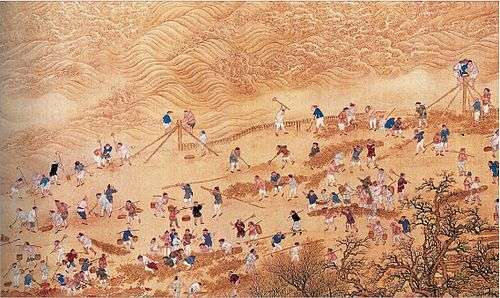

Based on circular-collar robe of West Asia, dragon robe was first adopted by the Tang dynasty (618–906 CE),[1] which embellished the robe with dragons to symbolize imperial power. The Mongols were the first to codify their use as emblems on court robes. As a result, the subsequent Ming emperors shunned them on formal occasions.[2] Though only royals could wear dragons, honoured officials could be granted the privilege of wearing "python robes" (蟒袍 or 蟒衣), which resembled dragons, only with four claws instead of five.[3]

Dragon robe of Tang dynasty

Dragon robe of Tang dynasty Dragon robe of Ming dynasty

Dragon robe of Ming dynasty Dragon robe of Qing dynasty

Dragon robe of Qing dynasty

A common misconception among Han Chinese was that Manchu clothing was entirely separate from Hanfu. In fact, Manchu clothes were simply modified Ming Hanfu but the Manchus promoted the misconception that their clothing was of different origin. Manchus originally did not have their own cloth or textiles and the Manchus had to obtain Ming dragon robes and cloth when they paid tribute to the Ming dynasty or traded with the Ming. These Ming robes were modofied, cut and tailored to be narrow at the sleeves and waist with slits in the skirt to make it suitable for falconry, horse riding and archery. [4] The Ming robes were simply modified and changed by Manchus by cutting it at the sleeves and waist to make them narrow around the arms and waist instead of wide and added a new narrow cuff to the sleeves.[5] The new cuff was made out of fur. The robe's jacket waist had a new strip of scrap cloth put on the waist while the waist was made snug by pleating the top of the skirt on the robe.[6] The Manchus added sable fur skirts, cuffs and collars to Ming dragon robes and trimming sable fur all over them before wearing them.[7] Han Chinese court costume was modified by Manchus by adding a ceremonial big collar (da-ling) or shawl collar (pijian-ling).[8] It was mistakenly thought that the hunting ancestors of the Manchus skin clothes became Qing dynasty clothing, due to the contrast between Ming dynasty clothes unshaped cloth's straight length contrasting to the odd-shaped pieces of Qing dynasty long pao and chao fu. Scholars from the west wrongly thought they were purely Manchu. Chao fu robes from Ming dynasty tombs like the Wanli emperor's tomb were excavated and it was found that Qing chao fu was similar and derived from it. They had embroidered or woven dragons on them but are different from long pao dragon robes which are a separate clothing. Flaired skirt with right side fastenings and fitted bodices dragon robes have been found[9] in Beijing, Shanxi, Jiangxi, Jiangsu and Shandong tombs of Ming officials and Ming imperial family members. Integral upper sleeves of Ming chao fu had two pieces of cloth attached on Qing chao fu just like earlier Ming chao fu that had sleeve extensions with another piece of cloth attached to the bodice's integral upper sleeve. Another type of separate Qing clothing, the long pao resembles Yuan dynasty clothing like robes found in the Shandong tomb of Li Youan during the Yuan dynasty. The Qing dynasty chao fu appear in official formal portraits while Ming dynasty Chao fu that they derive from do not, perhaps indicating the Ming officials and imperial family wore chao fu under their formal robes since they appear in Ming tombs but not portraits. Qing long pao were similar unofficial clothing during the Qing dynasty.[10] The Yuan robes had hems flared and around the arms and torso they were tight. Qing unofficial clothes, long pao, derived from Yuan dynasty clothing while Qing official clothing, chao fu, derived from unofficial Ming dynasty clothing, dragon robes. The Ming consciously modeled their clothing after that of earlier Han Chinese dynasties like the Song dynasty, Tang dynasty and Han dynasty. In Japan's Nara city, the Todaiji temple's Shosoin repository has 30 short coats (hanpi) from Tang dynasty China. Ming dragon robes derive from these Tang dynasty hanpi in construction. The hanpi skirt and bodice are made of different cloth with different patterns on them and this is where the Qing chao fu originated.[11] Cross-over closures are present in both the hanpi and Ming garments. The eighth century Shosoin hanpi's variety show it was in vogue at the tine and most likely derived from much more ancient clothing. Han dynasty and Jin dynasty (266–420) era tombs in Yingban, to the Tianshan mountains south in Xinjiang have clothes resembling the Qing long pao and Tang dynasty hanpi. The evidence fron excavated tombs indicates that China had a long tradition of garments that led to the Qing chao fu and it was not invented or introduced by Manchus in the Qing dynasty or Mongols in the Yuan dynasty. The Ming robes that the Qing chao fu derived from were just not used in portraits and official paintings but were deemed as high status to be buried in tombs. In some cases the Qing went further than the Ming dynasty in imitating ancient China to display legitimacy with resurrecting ancient Chinese rituals to claim the Mandate of Heaven after studying Chinese classics. Qing sacrificial ritual vessels deliberately resemble ancient Chinese ones even more than Ming vessels.[12] Tungusic people on the Amur river like Udeghe, Ulchi and Nanai adopted Chinese influences in their religion and clothing with Chinese dragons on ceremonial robes, scroll and spiral bird and monster mask designs, Chinese New Year, using silk and cotton, iron cooking pots, and heated house from China.[13]

The Spencer Museum of Art has six long pao robes that belonged to Han Chinese nobility of the Qing dynasty.[14] Ranked officials and Han Chinese nobles had two slits in the skirts while Manchu nobles and the Imperial family had 4 slits in skirts. All first, second and third rank officials as well as Han Chinese and Manchu nobles were entitled to wear 9 dragons by the Qing Illustrated Precedents. Qing sumptuary laws only allowed four clawed dragons for officials, Han Chinese nobles and Manchu nobles while the Qing Imperial family, emperor and princes up to the second degree and their female family members were entitled to wear five clawed dragons. However officials violated these laws all the time and wore 5 clawed dragons and the Spencer Museum's 6 long pao worn by Han Chinese nobles have 5 clawed dragons on them.[15]

Korea

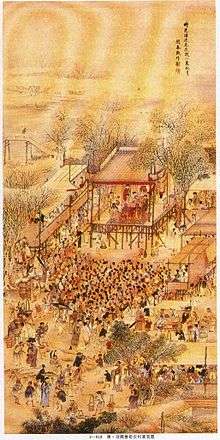

Korean kingdoms of Silla and Balhae first adopted the circular-collar robe, dallyeong, from Tang dynasty of China in the North-South States Period for use as formal attires for royalty and government officials. Kings of Goryeo dynasty used yellow dragon robes, which symbolized an equal status with the emperors of Chinese dynasties. Even after Goryeo was subjugated by the Mongol Empire into a vassal state, Goryeo kings were allowed to wear yellow dragon robes as the Mongols promised cultural autonomy of Goryeo. Goryeo kings at the time sometimes used the Mongol attire instead. Joseon dynasty once again adopted the style from Ming dynasty of China, then known in China as hwangnyongpo (hangul: 황룡포; hanja: 黃龍袍), as gonryongpo. Joseon dynasty ideologically submitted itself to Ming dynasty of China as a tributary state, and thus used red instead of yellow for its dragon robes, as yellow symbolized the emperor and red symbolized the king.

There was normally a dragon embroidered in a circle on gonryongpos. When a king or other member of the royal family wore a gonryongpo, they also wore an ikseongwan (익선관, 翼善冠)(a kind of hat), a jade belt, and mokhwa (목화, 木靴) shoes. They wore hanbok under gonryongpo. During the winter months, a fabric of red silk was used, and gauze was used during the summer. Red indicated strong vitality.

Gonryongpos have different grades divided by their color and belt material and a Mandarin square reflecting the wearer's status. The king wore scarlet gonryongpos, and the crown prince and the eldest son of the crown prince wore dark blue ones. The belts were also divided into two kinds: jade and crystal. As for the circular, embroidered dragon design of the Mandarin square, the king wore an ohjoeryongbo (오조룡보, 五爪龍補)--a dragon with 5 toes—the crown prince wore a sajoeryongbo (사조룡보, 四爪龍補)--a dragon with 4 toes—and the eldest son of the crown prince wore a samjoeryongbo (삼조룡보, 三爪龍補)--a dragon with three toes.[17]

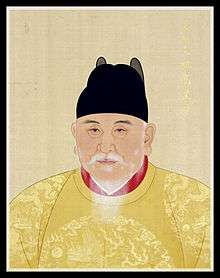

Taejo of Joseon's Gonryongpo

Taejo of Joseon's Gonryongpo Yeongjo of Joseon's Gonryongpo

Yeongjo of Joseon's Gonryongpo Gojong of the Korean Empire's Gonryongpo

Gojong of the Korean Empire's Gonryongpo

Vietnam

It is a casual dress worn by an emperor during an emperor Li or Nguyen dynasties.

Ryukyu

References

- Lee, Tae-ok. Cho, Woo-hyun. Study on Danryung structure. Proceedings of the Korea Society of Costume Conference. 2003. pp.49-49.

- Valery M. Garrett, Chinese Clothing: An Illustrated Guide (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 7. (cited in Volpp, Sophie (June 2005). "The Gift of a Python Robe: The Circulation of Objects in "Jin Ping Mei"". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 65 (1): 133–158. doi:10.2307/25066765. JSTOR 25066765.)

- Volpp, Sophie (June 2005). "The Gift of a Python Robe: The Circulation of Objects in "Jin Ping Mei"". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 65 (1): 133–158. doi:10.2307/25066765. JSTOR 25066765.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 0520300297.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 158. ISBN 0520300297.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 0520300297.

- Schlesinger, Jonathan (2017). A World Trimmed with Fur: Wild Things, Pristine Places, and the Natural Fringes of Qing Rule. Stanford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 1503600688.

- Chung, Young Yang Chung (2005). Silken threads: a history of embroidery in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam (illustrated ed.). Harry N. Abrams. p. 148. Retrieved Dec 4, 2009.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 103. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 104. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 105. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 106. ISBN 1555952380.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0521477719.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 115. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 117. ISBN 1555952380.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 149. ISBN 0520300297.

- (in Korean) Hanbok's rebirth Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine Kim Min-ja,《Koreana》No.22(Number 2)

- Gonryongpo Global Encyclopedia / Daum