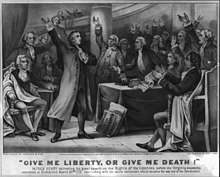

Give me liberty, or give me death!

"Give me liberty, or give me death!" is a quotation attributed to Patrick Henry from a speech he made to the Second Virginia Convention on March 23, 1775,[1] at St. John's Church in Richmond, Virginia.

Henry is credited with having swung the balance in convincing the convention to pass a resolution delivering Virginian troops for the Revolutionary War. Among the delegates to the convention were future U.S. Presidents Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

Publication

The speech was not published until The Port Folio printed a version of it in 1816.[2] The version of the speech that is known today first appeared in print in Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry, a biography of Henry by William Wirt in 1817.[2] There is debate among historians as to whether and to what extent Henry or Wirt should be credited with authorship of the speech and its famous closing words.[2][3]

Reception

According to Edmund Randolph, the convention sat in silence for several minutes afterward. Thomas Marshall told his son John Marshall, who later became Chief Justice of the United States, that the speech was "one of the boldest, vehement, and animated pieces of eloquence that had ever been delivered."[4] Edward Carrington, who was listening outside a window of the church, requested that he be buried on that spot. In 1810, he got his wish. The drafter of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, George Mason, said, "Every word he says not only engages but commands the attention, and your passions are no longer your own when he addresses them."[4] More immediately, the resolution, declaring the United Colonies to be independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain, passed, and Henry was named chairman of the committee assigned to build a militia. Britain's royal governor, Lord Dunmore, reacted by seizing the gunpowder in the public magazine at Williamsburg—Virginia's equivalent of the battles of Lexington and Concord.[4] Whatever the exact words of Henry were, "scholars, understandably, are troubled by the way Wirt brought into print Henry's classic Liberty or Death speech," wrote historian Bernard Mayo. "Yet . . . its expressions. . . seemed to have burned themselves into men's memories. Certainly, its spirit is that of the fiery orator who in 1775 so powerfully influenced Virginians and events leading to American independence."[4]

Precursors

There had been similar phrases used preceding Henry's speech. The 1713 play, Cato, a Tragedy, was popular in the Colonies and well known by the Founding Fathers, who would quote from the play. George Washington had this play performed for the Continental Army at Valley Forge.[5] It contains the line, "It is not now time to talk of aught/But chains or conquest, liberty or death" (Act II, Scene 4). The phrase "Liberty or Death" also appears on the Culpeper Minutemen flag of 1775.[6]

In the opera Artemisia (1657) there is an aria called "Dammi morte o libertà" (lit:"Give me death or freedom") but the context is different, since in this aria with "Freedom" isn't meant political freedom: Oronta is asking Amor (personification of love) to either free her from love's bonds or to kill her, since, love's pains are too hard for her to suffer. This is explained in the first stanza (translated: Give me death or freedom / Oh blind Amor, that so much sufferings, / So much troubles, so much chains / the heart can't bear).

In Handel's oratorio Judas Maccabeus, the hero sings 'Resolve, my sons, on liberty or death' (1746).

"Liberty or death" in other contexts

Phrases equivalent to liberty or death have appeared in a variety of other places:

The national anthem of Uruguay, "Orientales, la Patria o la Tumba", contains the line "¡Libertad o con gloria morir!" (Liberty or with glory to die!).[7]

The national anthem of Chile, "Canción Nacional", contains the line "Que oh la tumba serás de los libres, o el asilo contra la opresión" (May the tomb of the free will you be, or a refuge against the oppression)

The Declaration of Arbroath made in the context of Scottish independence in 1320 as a letter to the Pope contained the line "It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself". The Declaration is commonly cited as an inspiration for the United States Declaration of Independence by many, including the US Senate[8] and it is possible that Henry knew of the Declaration when he wrote his speech.

The motto of Greece is "Liberty or Death" (Eleftheria i thanatos). It arose during the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s, where it was a war cry for the Greeks who rebelled against Ottoman rule.[9]

A popular (and possibly concocted) story in Brazil relates that in 1822, the emperor Pedro I uttered the famous "Cry from [the river] Ipiranga", "Independence or Death" (Independência ou Morte), when Brazil was still a colony of Portugal.[10]

During the Russian Civil War, the flag used by Makhno's anarchist Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine had the dual slogans "Liberty or Death" and "The Land to the Peasants, the Factories to the Workers".[11]

In March 1941 the motto of the public demonstrations in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia against signing the treaty with Nazi Germany was "Better grave than slave" (Bolje grob nego rob).[12]

During the Indonesian National Revolution the Pemuda (youth) used the phrase "Merdeka atau Mati" which means "Freedom or Death".[13]

In 2012, in China, Ren Jianyu, a 25-year-old former college student "village official" was given a two-year re-education through labor sentence for an online anti-CPC speech. A T-shirt of Ren's saying "Give me liberty or give me death!" (in Chinese) has been taken as evidence of his anti-social guilt.[14][15]

See also

- Liberty or Death (disambiguation)

- Join, or Die

- Live Free or Die

- Liberté, égalité, fraternité

- Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death

References

Footnotes

- Hart, James D.; Leininger, Phillip (1995). The Oxford Companion to American Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 286. ISBN 9780195065480.

- Cohen (1981), p. 702n2.

- Cohen (1981), pp. 703–04, 710ff.

- "Patrick Henry and His Famous Speech". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2014 – via iCitizen Forum. Excerpt from Aron, Paul (2008). "John Adams". We Hold These Truths. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, in association with The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. pp. 86–88.

- Randall (1997), p. 43.

- "Culpepper Flags".

- History about the Anthem of Uruguay Embassy of Uruguay in Argentina

- "Senate Resolution 155 – Designating "National Tartan Day"". US Congress. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- Crampton, William (1991). Complete Guide to Flags. Gallery Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8317-1605-9.

- Barman, Roderick J. (1988). Brazil: The Forging of a Nation, 1798–1852. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8047-1437-2.

- Eikhenbaum, Vsevolod M. (Volin), The Unknown Revolution, 1917-1921: Book III: Struggle for the Real Social Revolution, Part II: Ukraine (1918-1921), Free Life Editions (1974), ISBN 0-914156-07-1, ISBN 978-0-914156-07-9

- Job, Cvijeto (March 15, 1992). "Requiem for a Nation". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Padmodiwiryo, Suhario (2015). Student Soldiers: A Memoir of the Battle that Sparked Indonesia's National Revolution. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. p. 165. ISBN 9789794619612. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Yu Jincui (October 12, 2012). "Punishing Criticisms Outdated in Today's China". Global Times. Beijing. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- "Chongqing Village "Liberty or Give Me Death" T shirt Is Evidence for Detention". 大河报 (in Chinese). October 11, 2012. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

Works cited

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Cohen, Charles (October 1981). "The 'Liberty or Death' Speech: A Note on Religion and Revolutionary Rhetoric". The William and Mary Quarterly. 38 (4): 702–717. doi:10.2307/1918911. JSTOR 1918911.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nelson, Craig (2006). Thomas Paine, Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03788-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Randall, William (1997). George Washington: A Life. New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-2779-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raphael, Ray (2004). Founding Myths: Stories that Hide Our Patriotic Past. New York: New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-921-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wirt, William (1816). Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry. Philadelphia: Webster. OCLC 4519869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Give me liberty, or give me death! |