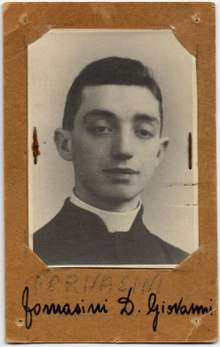

Giovanni Fornasini

Giovanni Remo Fornasini (Pianaccio, 23 February 1915 – San Martino di Caprara, 13 October 1944) was an Italian priest, anti-fascist and patriot in Bologna. He was murdered by a German Nazi Waffen SS soldier and was posthumously awarded Italy's Gold Medal of Military Valour. As of 2018, he is being investigated by the Catholic Church towards his possible canonisation.

Giovanni Remo Fornasini | |

|---|---|

Don Giovanni Fornasini | |

| Born | 23 February 1915 Pianaccio, Lizzano in Belvedere, Bologna, Italy |

| Died | 13 October 1944 (aged 29) San Martino di Caprara, Marzabotto, Bologna, Italy |

| Burial place | San Tommaso a Sperticano, Marzabotto |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Priest |

| Awards | |

Biography

An editorial comment on the sources

The sources are fragmentary. None gives a complete account of Fornasini's life. Although they are broadly consistent, they sometimes differ in detail.[Note 1] Where they disagree, their varying accounts are set out below as numbered alternatives.

Early years

Fornasini was born in Pianaccio, a frazione of the Italian comune Lizzano in Belvedere, in the then Province of Bologna, Kingdom of Italy.[1][Note 2] His parents were Angelo (a.k.a. Anselmo) Fornasini (1887-1938), a charcoal burner, and his wife Maria née Guccini (1887-1951). He had an elder brother, Luigi (born 1912).[2] In 1924[3] or 1925,[4][5][6] the family relocated to Porretta Terme, Bologna. Angelo had been gassed in World War I, and could no longer carry on his trade; instead, he became a postman, delivering letters. Maria got a job as an attendant at a thermal bath in the town.[3][6] Giovanni studied at Collegio Albergati in Porretta Terme;[2][6] but did not graduate,[3] and is recorded as not having been a good student.[4][5] After leaving school, he worked for some time as a lift boy in the Grand Hotel, Bologna.[3]

He seems to have discovered a vocation. In 1931, he entered the seminary of Borgo Capanne.[5][6][Note 3] That seminary closed in 1932, and he transferred to the Archepiscopal Seminary of Bologna at Villa Revedin, and later to the Pontifical Seminary of the Region of Bologna.[6] On 2 February 1934, he made his priestly vow,[2] and continued his theological studies. On 29 March 1940, he was ordained subdeacon;[1] on 7 June 1941, deacon;[3] and on 28 June 1942, priest (by Cardinal Giovanni Nasalli Rocca di Corneliano, in San Petronio Basilica, Bologna).[7][10][11] On being made subdeacon, he was appointed assistant to Don Giovanni Roda, parish priest of Sperticano, a frazione of Marzabotto, Bologna,[2] a parish of about 400 people;[1] and on being made priest, assistant priest (Italian: vicario coadiutore) in Sperticano.[1] He celebrated his first spoken Masses at Pianaccio, at San Luca and at Porretta;[6] and his first solemn (i.e. sung) Mass on 12 July 1942, in the church of San Tommaso a Sperticano.[2] In his homily at Porretta [6] or at Sperticano [3] he said, "The Lord has chosen me to be an urchin among the urchins" (Italian: Il Signore mi ha scelto monello fra i monelli).[Note 4]

Parish priest

Don Giovanni Roda was elderly. The sources relating to his death are inconsistent. (1) He died on 21 August 1942.[2] Don Giovanni Fornasini had been named his likely successor on 20 July,[2][10] and was appointed spiritual adviser in Sperticano on 21 August.[11] (2) Don Giovanni Roda died on 20 July. The same day, Don Giovanni Fornasini was appointed spiritual adviser in Sperticano. On 21 August, he was nominated as the new parish priest.[3][4][5] (3) On 21 August, Don Giovanni Fornasini succeeded Don Giovanni Roda as parish priest after the latter's death.[1] (4) All sources agree that Don Giovanni Fornasini was formally installed as parish priest in Sperticano on 27 September.[3][4][5]

Fornasini's pastoral work began during a turbulent time for Italy during World War II.[4][6] He opened a school similar to the one he had attended as a boy in Porretta. He also soon gained a reputation as a man of action.[3][6] Don Angelo Serra, another parish priest in Bologna, said that the parish of Sperticano was transformed by Don Giovanni's zeal.[1] Don Lino Cattoi, who had been his fellow student, said of his time in Sperticano, "I cannot explain the life he led there: he seemed always to be running. He was always around trying to free people from their difficulties, and to solve their problems. He had no fear. He was a man of great faith, and was never shaken" (Italian: Io non so spiegarmi la vita che ha fatto quell'uomo lì: correva dappertuto. Era sempre in giro per cercare di liberare la gente dalle difficoltà, di risolvere i loro problemi. Non aveva paura. Era un uomo di gran fede e sempre coerente).[12]

On 25 July 1943, Italian dictator Mussolini was overthrown. Fornasini ordered his church bells to be rung in celebration.[8][10][16]

Bologna was a city of strategic military importance during World War II. It was heavily bombed by the Allies three times during 1943: on 24 July, 25 September and 27 November. On 3 September, the Kingdom of Italy signed an armistice with the Allies; but the north of Italy, including Bologna, was still under German (i.e. Nazi) control. Perhaps unsurprisingly, accounts of Fornasini's pastoral activities during that time are incomplete. It has been said that his chief characteristic was, that he was everywhere (Italian: Sua caratteristica principale fu l'ubiquità).[3] After at least one of those bombings, he gave shelter to survivors in his own rectory.[6][7] Riding his beloved bicycle, he gave assistance in nearby parishes;[6] including San Cristoforo di Vedegheto, whose priest who had left for health reasons.[1] After the bombing of Reno, Bologna on 27 November, he was to be seen everywhere, smiling, comforting people in distress.[3][6] Serra said: "On the sad day of 27 November 1943, when 46 of my parishioners were killed in Lama di Reno by Allied bombs, I remember Don Giovanni working as hard in the rubble with his pickaxe as if he had been trying to rescue his own mother" (Italian: Venne il triste 27 novembre 1943 col suo bombardamento a falciare 46 dei miei parrocchiani a Lama di Reno. Lo ricordo don Giovanni col piccone in mano lavorare con tanta forza come se dovesse scavare da quelle macerie la mamma sua).[1]

Several sources say that he had some sort of connection with Italian partisans who were fighting the Nazis. The sources do not agree with each other; and one source warns that the truth may no longer be possible to determine.[17] (1) He was chaplain to a partisan brigade, Brigata Partigiana Stella Rossa.[3][18] (2) He declared, "I am pastor to all, no-one excepted. The partisans too are among the baptised, just like my parishioners; and if they will not come down, I will go up" (Italian: Io sono parroco di tutti, nessuno escluso. Anche i partigiani sono dei battezzati, come i miei parrocchiani; se loro non scendono, io salgo).[Note 5] He rebuked the brigade's leader, Mario Musolesi (nicknamed Il Lupo, "The Wolf"), because men under his command had killed Italians – and, he was listened to. He was posthumously said to have been a partisan from 13 November 1943 until the day of his death.[3] (3) He was connected to that brigade.[8][10][19] (4) He was close to the partisans; or, he cohabited with, but did not collaborate with, them.[17]

Accounts of the last few months of his life are consistent in essence, but differ in detail. (1) On 24 June 1944, he gave Christian burial to the four or five murdered victims of the Nazi atrocity of 22 June at Stazione di Pian di Venola, Marzabotto; even though the Nazis had ordered that no such ceremony take place; and, he delivered a moving eulogy.[1] At some later date, partisans blew up a train in a railway tunnel near Misa, and the Nazis took Italian civilians as hostages. On 30 July, Fornasini intervened to secure their release. In August, he was again at Pian di Venola, this time offering his own person in exchange for captives of the Nazis. In September, he and Don Gabriele Bonani helped three British prisoners to escape. He was arrested at Pioppe di Salvaro. On 5 September, he buried the dead at Ca' di Biguzzi. On 8 September, the Nazis garrisoned (i.e. installed soldiers in) his rectory. The same day, he wrote his last will and testament.[3] (2) He wrote his last will and testament on 10 September.[6] (3) In July 1944, the Germans took 30 Italian civilians prisoner at Pioppe di Salvaro. He intervened, offering his own person in exchange. The Germans murdered only 12 of them.[1][13] On 30 July, a train loaded with fuel blew up. Two German soldiers died, and the Germans took 20 Italians as hostages. He gathered evidence which persuaded the Germans that the explosion had been an accident; and, the hostages were released. He subsequently convinced the Germans that several other acts of sabotage had been committed by Tuscan partisans, and that local people had not been involved; thus saving many lives.[13] He did not manage to intervene before the massacre at Corsaglia (Marzabotto); the place where he later lost his own life.[13] (4) According to Don Angelo, Don Giovanni persuaded the German commander to rescind his order to lay waste to Marzabotto by the gift of money and a pig. However, the barbarians had come to rend the sheep; and, as the Gospels teach, the good shepherd lays down his life for his sheep.[1]

On 12 October, he intervened to protect one or more women who were being maltreated by one or more Germans. (1) An SS officer had designs on one of the girls sheltered in Fornasini's rectory. Fornasini was forced to attend a squalid German party to celebrate her birthday; where, despite insults and mockery, he protected her.[1][6] (2) Two young women were being abused by several SS soldiers. He made them desist.[3][Note 6][Note 7] (3) A Nazi official tried to drag a girl away, but Fornasini faced him down.[12][18][19]

Death and burial

The best contemporary account may be in the diary of Don Amadeo Girotti (1881/82-1974), parish priest of San Michele Arcangelo di Montasico in Bologna. He knew Fornasini well: he had made confession to him at least twice, and shortly after the murder called him "Don Fornasini, dearest to me" (Italian: il mio carissimo Don Fornasini).[9][Note 8]

Between 29 September and 5 October 1944, Waffen SS troops carried out near Bologna a mass killing of Italian civilians remembered as the Marzabotto massacre. The number of deaths is estimated to have been 770. Fornasini's brother priest Don Ubaldo Marchioni was among the first victims, murdered in Marzabotto on 29 September.[20]

Fornasini died on 13 October 1944.[1][2][21] The circumstances of his death are shrouded in mystery.[4][5][6][Note 9] (1) On 18 May 1945, Don Amadeo said that a Nazi officer had given Fornasini permission to bury the dead at San Martino del Sole, Marzabotto on 13 October 1944; but that he had been cynically murdered there; that his body was identified on 14 October; and that he had been shot in the chest.[3][9] (Don Amadeo had learned of the death on 18 October 1944.)[9] (2) On 13 October, Fornasini followed the Germans to Caprara.[6] (3) While burying the dead at Casaglia di Caprara, which the Nazis had forbidden, he accused a Nazi officer of complicity in the Marzabotto massacre, and was at once shot down.[8] (4) He accused an officer in the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division Reichsführer-SS of complicity in the Marzabotto massacre. He was shot at point-blank range and decapitated.[10] (5) He accused a German officer of being responsible for the massacre. The officer replied, that that was a lie, and invited Fornasini to inspect Marzabotto; where he shot him in the head, among all the other corpses there.[13]

World War II neared its end; the Nazis had withdrawn from Italy; and the winter snows had melted. (1) On 21 April 1945, Luigi recovered the body of his brother Giovanni, and some days later gave it makeshift burial at Sperticano.[3] (2) Luigi discovered the body of his brother on 22 April.[6][9] (3) The body had been decapitated.[14][24] (4) That temporary burial took place on 24 April.[2] (5) All sources agree that on 13 October 1945, Fornasini was given Christian burial in his own church of San Tommaso a Sperticano.[2][3][9]

Posthumous recognition

On 19 May 1950, the President of Italy, Luigi Einaudi, conferred upon Fornasini posthumously Italy's Gold Medal of Military Valour,[2][3] a high distinction. The award was presented to his mother, Maria, on 2 June 1951.[5][Note 10] The citation reads:[25]

Nella sua parrocchia di Sperticano, dove gli uomini validi tutti combattevano sui monti per la libertà della Patria, fu luminoso esempio di cristiana carità. Pastore di vecchi, di madri, di spose, di bambini innocenti, più volte fece loro scudo della propria persona contro efferati massacri condotti dalle SS. germaniche, molte vite sottraendo all’eccidio e tutti incoraggiando, combattenti e famiglie, ad eroica resistenza. Arrestato e miracolosamente sfuggito a morte, subito riprese arditamente il suo posto di pastore e di soldato, prima tra le rovine e le stragi della sua Sperticano distrutta, poi a San Martino di Caprara dove, pure, si era abbattuta la furia del nemico. Voce della Fede e della Patria, osava rinfacciare fieramente al tedesco l’inumana strage di tanti deboli ed innocenti richiamando anche su di sé le barbarie dell’invasore e venendo a sua volta abbattuto, lui Pastore, sopra il gregge che, con estremo coraggio, sempre aveva protetto e guidato con la pietà e con l’esempio. – S. Martino di Caprara, 13 ottobre 1944

An English translation:

In his parish of Sperticano, where all true men fought in the mountains for the freedom of their Fatherland, he was a shining example of Christian charity. Pastor to the old, to the mother, to the bride, to the innocent child, he several times shielded them with his own body against the heinous atrocities of the German SS, saving many lives from death and encouraging all, both the fighters and their families, to heroic resistance. Arrested, miraculously escaping death, he at once and boldly resumed his role as pastor and soldier, first among the ruins and massacres of his destroyed Sperticano, then at San Martino di Caprara; where, however, he was struck down by the ferocity of the enemy. The voice of Faith and of Fatherland, he had dared fiercely to condemn the inhuman German massacres of so many of the weak and of the innocent, thereby calling down upon himself the barbarity of the invader and being slain; he, the Shepherd who had always with the utmost courage protected and guided his flock by his piety and by his example. – San Martino di Caprara, 13 October 1944

An elementary school in Porretta Terme, Scuola Primaria "Don Giovanni Fornasini", is named in his honour.[8][10][26] A street in Bologna, Via Don Giovanni Fornasini, commemorates his name;[8] as do other places in the Province of Bologna.[3][8][10]

Fornasini has been called "the angel of Marzabotto" (Italian: l'angelo di Marzabotto);[1][2][3] and also, together with his murdered fellow priests Ferdinando Casagrande and Ubaldo Marchioni, one of "the three martyrs of Monte Sole" (Italian: il tre martiri di Monte Sole).[8][27][28]

On 13 October 1978, inhabitants of Marzabotto began to press for official recognition by the Church of il tre martiri di Monte Sole.[15] Their arguments did not go unheard. On 19 August 1998, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints granted permission for inquiries to be opened into the lives and works of those three priests.[4][29][30] On 18 October 1998, in Marzabotto, Cardinal Giacomo Biffi opened formal proceedings for their beatification.[6][8][10] Since that day, all three have been entitled to be honoured as Servants of God. On 20 November 2011, Cardinal Carlo Caffarra formally declared in San Petronio Basilica, Bologna to a full congregation (which included, among others, both civic dignitaries and relatives of the murdered priests) that the Archdiocese of Bologna had completed all three investigations, and that their findings would be communicated to the Holy See for further processing.[7][14][31]

In the 2009 film The Man Who Will Come (Italian: L'uomo che verrà) (which concerns the Marzabotto massacre), actor Raffaele Zabban portrayed the small role of Fornasini.[32]

In 2014, Italian musician Alessandro Berti created what he called a spettacolo,[Note 11] a work consisting of a spoken narration with musical sung and instrumental accompaniment, which relates the story of the last year of Fornasini's life. It is called Un cristiano: Don Giovanni Fornasini, l'angelo di Marzabotto, or, Un cristiano: Don Giovanni Fornasini a Monte Sole. It has been performed more than once.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40]

Notes

- This is perhaps not surprising for someone from such a humble background – and also for events during wartime, when accurate records may not have been kept or may not have survived. Some sources supply what look like factual items of information about parts of his life, but elsewhere what may be subjective opinions. Until an authoritative biography is written, readers must form their own judgments. An encyclopaedia must avoid original research, and must not combine sources to infer something which no individual source says.

- There is a question concerning his date of birth. Some sources say that he was born on 23 February 1915.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] Other sources say that he was born on 23 November 1915.[1][10][11][12] Other sources say that he was 29 when he died; which is consistent with February 1915, but not with November 2015.[13][14][15] Although the November date may have arisen from a misreading of 23.ii.1915 as 23.11.1915, this question can only be settled for certain by inspection of contemporary written records.

- His family was poor. It seems unlikely that they had the money to finance him during his religious studies. He may have been supported by a charitable grant. No record which might answer this question seems to have survived, or to be easily accessible.

- The Italian word monello is not easy to translate into a single English word. In addition to "urchin", Google Translate also suggests "brat", "guttersnipe", "rascal" and "scamp". However, all those words relate to, and in English Wikipedia some redirect to, street children.

- An uphill journey of 9 kilometres (5.6 miles); Don Giovanni sometimes made it twice a day.[1]

- The month in this passage in this source is in doubt. It says that that confrontation between Fornasini and the Nazi or Nazis occurred on 12 September, and that Fornasini was killed the next day, i.e. on 13 September. All other sources say that he was killed on 13 October, after the Marzabotto massacre; as does this same source, elsewhere.

- The Italian word abusassero ("abusing") in this source is broad enough to include verbal, mental, or some kind of physical abuse.

- Only part of that diary is accessible online; the uploaded part breaks off at 18 October 1944.

- Some sources include more details of how he died than those included in the main text.[8][13][22][23] Such sources should be perhaps approached with caution – they are not contemporary, and they are inconsistent both with each other and with earlier sources. Warnings in other sources about the 'shroud of mystery' surrounding his death should also be kept in mind.

- Maria died three weeks later, on 23 June 1951.[2]

- According to Google Translate, the Italian word spettacolo translates into English as "show", "spectacle" or "performance". The article it:Spettacolo in Italian Wikipedia suggests that none of those English words quite catches the meaning of the Italian word.

References

- "Don Giovanni Fornasini – L'angelo di Marzabotto". bibliotecapersicetana.it (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Stefano (3 December 2013). "don Fornasini Biografia". montesole.eu (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Fornasini Giovanni Remo". Storia e memoria di Bologna (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Zompì, Gabriele. "Pianaccio e don Giovanni Fornasini". ilcomuneinforma.it (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "I sacerdoti". paxchristibologna.it (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Servo di Dio Giovanni Fornasini Sacerdote e martire". santiebeati.it (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Bologna: tre martiri verso la beatificazione". Zenit (in Italian). 17 November 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Don Giovanni Fornasini". Associazione Nazionale dei Partigiani d'Italia (in Italian). 25 July 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Stefanato, Cesare Romano (2000). "L'angelo di Marzabotto don Giovanni Fornasini". Boccia "Bocia Cesarin": An Historical Link Italy - Australia. Little Red Apple. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-1875329199. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Cousin, Roger (11 February 2013). "Fornasini Giovanni" (in French). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Ex-alunni". seminarioflaminio.it (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Lucà, Marco. "Il corragio di essere giusti, storia di don Giovanni". agesci.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Garibaldi, Luciano (31 May 2016). "Memorie di un'epoca – Preti martiri in Emilia: una storia da riscoprire". riscossacristiana.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Andrini, Stefano (12 November 2011). "Il sangue e l'altare a Monte Sole". avvenire.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Mele, Nicodemo (21 November 2011). "I tre sacerdoti eroi verso la beatificazione | Morirono a Marzabotto". ilrestodelcarlino.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Lorenzetto, Stefano (9 November 2007). "Caro direttore ti racconto il tuo funerale". Il Giornale (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "The beatification of Father Giovanni Formasini". historiana.eu. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Biagi, E. "L'uccisione di don Fornasini". bibliotecasalaborsa.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Di Pietrantonio, Luciano (28 September 2014). "70 anni dalla strage di Marzabotto: occorre ricordare". abitarearoma.net (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Servo di Dio Ubaldo Marchioni". santiebeati.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Processo di beatificazione dei tre sacerdoti trucidati a Monte Sole". Bologna (in Italian). 18 November 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Jennings, Christian (22 September 2016). At War on the Gothic Line: Fighting in Italy 1944–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1472821645. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Marchione, Margherita (2001). Yours Is a Precious Witness: Memoirs of Jews and Catholics in Wartime Italy. ISBN 9780809140329. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "1944 – Settembre 29.30 – Strage di Marzabotto". anpireggioemilia.it (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Fornasini Don Giovanni". Quirinal Palace (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Scuola Primaria "Don Giovanni Fornasini"". comuniecitta.it (in Italian). Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "I tre sacerdoti "martiri" di Montesole". Bologna Seminary (in Italian). 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Martiri di Monte Sole" (in Italian). Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "A Roma la causa di beatificazione dei tre parroci assassinati a Marzabotto" (in Italian). 18 November 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Servo di Dio Don Giovanni Fornasini, Sacerd. sec. + 1944". chiesadibologna.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Tre nuovi "Beati" per la Chiesa di Bologna". Bologna Today (in Italian). 21 November 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- The Man Who Will Come (2009) on IMDb

- ""Un cristiano" Don Giovanni Fornasini a Montesole. Spettacolo teatrale a Marzabotto". unioneappennino.bo.it (in Italian). 26 June 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ""UN CRISTIANO" spettacolo su don Giovanni Fornasini tournée autunno 2014". Associazone cattolica esercenti cinema (in Italian). 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Pièce teatrale "Un cristiano: Don Giovanni Fornasini a Monte Sole" - ore 20.45 Parrocchia Quarto Inferiore" (in Italian). 2 October 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "A TEATRO NELLE CASE 2014 FESTIVAL D'AUTUNNO SENTIRE VICINO, GUARDARE LONTANO UN CRISTIANO. Don Giovanni Fornasini a Monte Sole". teatrodelleariette.it (in Italian). 2 October 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Un cristiano. Don Giovanni Fornasini a Monte Sole". anpi-anppia-bo.it (in Italian). 20 April 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Marino, Massimo; Brighenti, Matteo (27 April 2017). "Resistenza!" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Un parroco a Monte Sole. "Un cristiano" di Alessandro Berti". bolognateatri.net (in Italian). 8 May 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Cipriani, Antonio (4 December 2016). "Il coraggio di un cristiano, don Giovanni eroe semplice di Marzabotto". globalist.it (in Italian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.