George Brown (Canadian politician)

George Brown (November 29, 1818 – May 9, 1880) was a Scottish-Canadian journalist, politician and one of the Fathers of Confederation; attended the Charlottetown (September 1864) and Quebec (October 1864) conferences.[1] A noted Reform politician, he is best known as the founder and editor of the Toronto Globe, Canada's most influential newspaper at the time. He was an articulate champion of the grievances and anger of Upper Canada (Ontario). He played a major role in securing national unity. His career in active politics faltered after 1865, but he remained a powerful spokesman for the Liberal Party promoting westward expansion and opposing the policies of Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald.

George Brown | |

|---|---|

| |

| Premier of Canada West | |

| In office August 2, 1858 – August 6, 1858 | |

| Preceded by | John A. Macdonald |

| Succeeded by | John A. Macdonald |

| Senator for Lambton, Ontario | |

| In office December 16, 1873 – March 25, 1880 | |

| Appointed by | Alexander Mackenzie |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 29, 1818 Alloa, Clackmannanshire, Scotland |

| Died | May 9, 1880 (aged 61) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Political party | Clear Grit Party |

| Profession | Journalist, publisher, politician |

| Signature | |

Biography

George Brown was born in Alloa, Clackmannanshire, Scotland, on November 29, 1818. His father, an evangelical Presbyterian, was committed to civil and religious liberty, progress, and laissez-faire economics. He was an enemy of Tory aristocratic privilege, and provided a good education for his son, who brought similar beliefs to the New World.[2]

New York City

The family emigrated to New York in 1837, and began publishing newspapers.[2]

Brown discovered he appreciated British parliamentarianism more than American republicanism. He visited Canada several times and was invited to move there in 1843 by Presbyterians.

Toronto

Brown began the Toronto Banner in 1843. It was a Presbyterian weekly supporting Free Kirk principles and political reform. Brown's father raised the money and founded a weekly newspaper, The Globe in 1844, and later became a daily news source. Filled with strong editorials on religious and political affairs, The Globe quickly became the leading Reform newspaper in the Province of Canada. In 1848, he was appointed to head a Royal Commission to examine accusations of official misconduct in Provincial Penitentiary of the Province of Upper Canada at Kingston. The "Brown Report", which Brown drafted early in 1849, included sufficient evidence of abuse to set in motion the termination of warden Henry Smith.[2] Brown's revelations of poor conditions at the Kingston penitentiary were heavily criticized by John A. Macdonald and contributed to the tense relationship between the two rival politicians.

Issues

Brown attacked slavery in the United States and in 1850, helped found the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada. This society was founded to end the practice of slavery in North America, and individual members aided former American slaves reach Canada via the Underground Railroad.[3] As a result, black Canadians enthusiastically supported Brown's political ambitions.

Catholics, however, were another matter. He vehemently ridiculed and denounced the Catholic Church, Jesuits, priests, nunneries, etc. His newspaper promoted the strident speeches of ex-Catholic priest Alessandro Gavazzi, which incited mob violence in 1853 with nine dead in Montreal.[4]

Brown was elected to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada in 1851. He reorganized the Clear Grit (Liberal) Party in 1857, supporting, among other things, the separation of church and state, the annexation of Rupert's Land, and a small government. But the most important issue for George Brown was representation by population, where electoral districts would be divided so that each one contained a roughly equal number of electors.[2]

From the Act of Union in 1840, the Canadian colonial legislature had been composed of an equal number of members from Canada East (Lower Canada, Quebec) and Canada West (Upper Canada, Ontario, Canada). In 1841, Francophone-dominated Lower Canada had a larger population, and the British colonial administration hoped that the Canadiens in Lower Canada would be legislatively pacified by a coalition of Loyalists from Lower Canada with the Upper Canadian side. But during the 1840s and 1850s, as the population of Upper Canada grew larger than the Canadien population of Lower Canada, the opposite became true. Brown believed that the larger population deserved to have more representatives, rather than an equal number from Upper and Lower Canada. Brown's pursuit of this goal of righting what he perceived to be a great wrong to Canada West[5] was accompanied at times by stridently critical remarks against French Canadians[6] and the power exerted by the Catholic population of Canada East over the affairs of largely Protestant Canada West, referring to the position of Canada West as "a base vassalage to French-Canadian Priestcraft."[6]

.jpg)

Premier

For a period of four days in August 1858, political rival John A. Macdonald lost the support of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada on a non-confidence vote and his cabinet had to resign. After Alexander Galt declined the opportunity, George Brown attempted to form a ministry with Antoine-Aimé Dorion. At the time, newly appointed ministers had to resign their seats and run in by-elections. When members of Brown's ministry resigned their seats to get re-elected, supporters of Macdonald called for a vote of non-confidence, which passed and thus forced Brown and his government to resign before they had re-taken their seats. Brown was the de facto premier of Province of Canada in 1858. The short-lived administration was called the Brown-Dorion government, named after the co-premiers George Brown and Antoine-Aimé Dorion. This episode was termed the "double shuffle."[7]

Confederation

George Brown resigned from the Coalition in 1865 because he was not happy with the United States. Brown thought Canada should pursue free trade, while the conservative government of John A. Macdonald and Alexander Galt thought Canada should increase tariffs.

During the Quebec Conference, Brown argued strongly in favour of an appointed Senate. Like many reformers of the time, he saw Upper Houses as inherently conservative in function, serving to protect the interests of the rich, and wished to deny the Senate the legitimacy and power that naturally follows with an electoral mandate.[8]

The success of the Quebec Conference pleased Brown particularly by the prospect for the end of Lower Canadian interference in the affairs of Canada West. "Is it not wonderful?" he wrote to his wife Anne after the Quebec Conference, "French-Canadianism is entirely extinguished."[9][10][11][12] By this he may have meant either that he was of the view that English-speaking Canada West had emerged triumphant over French Canadians[13] or that Confederation would put an end to French Canadian domination of the affairs of what would become the province of Ontario.[12]

Brown realized, nevertheless, that satisfaction for Canada West would not be achieved without the support of the French-speaking majority of Canada East. In his speech in support of Confederation in the Legislature of the Province of Canada on February 8, 1865, in which he spoke glowingly of the prospects for Canada's future,[14] Brown insisted that "whether we ask for parliamentary reform for Canada alone or in union with the Maritime Provinces, the views of French Canadians must be consulted as well as ours. This scheme can be carried, and no scheme can be that has not the support of both sections of the province".[15] Following the speech, Brown was praised by the Quebec newspaper Le Canadien[16] as well as by the Rouge paper, L'Union Nationale.[16] Although he supported the idea of a legislative union at the Quebec Conference,[17] Brown was eventually persuaded to favour the federal view of Confederation, closer to that supported by Cartier and the Bleus of Canada East, as this was the structure that would ensure that the provinces retained sufficient control over local matters to satisfy the need of the French-speaking population in Canada East for jurisdiction over matters essential to its survival.[16] However Brown, like Macdonald, remained a proponent of a stronger central government, with weaker constituent provincial governments.[16]

In 1867, Brown ran for a seat in the House of Commons of Canada. As leader of the provincial Liberals, he also ran for a seat in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. His intention was to become Premier but he failed to win election to either chamber. He was widely seen as the leader of the federal Liberals in the 1867 federal election. The Liberals were officially leaderless until 1873, but Brown was considered the party's "elder statesman" even without a seat in the House of Commons, and was regularly consulted by leading Liberal parliamentarians. Brown was made a senator in 1873.[18]

Post-parliamentary career and death

Brown fought endless battles with the typographical union from 1843 to 1872. He paid union wages, not because of generosity but only when the power of the union forced it upon him.[19]

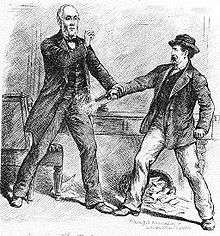

On March 25, 1880, a former Globe employee, George Bennett, dismissed by a foreman, shot George Brown at the Globe office. Brown caught his hand and pushed the gun down, but Bennett managed to shoot Brown in the leg. What seemed to be a minor injury turned gangrenous, and seven weeks later, on May 9, 1880, Brown died from the wound. Brown was buried at Toronto Necropolis.[20] Bennett was hanged for the crime.

His wife, Anne Nelson, returned to Scotland thereafter where she died in 1906. She is buried on the southern terrace of Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh. The grave also commemorates George Brown. In 1885 his daughters Margaret and Catherine were two of the first women to graduate from University of Toronto.

Legacy

After an accident involving a horse-drawn sleigh where Brown nearly drowned in the Don River, Brown took William Peyton Hubbard under his wing and encouraged his political career. Popular legend has it that Brown was rescued by Hubbard, but Hubbard stated he was not present at that event and that he only agreed to work for Brown as a favour to his brother, who operated the livery service. Hubbard went on to 13 straight years as alderman for the elite Ward 4, sitting on the powerful Board of Control, and become Toronto's first black deputy mayor, functioning as acting mayor on several occasions.[21]

Brown's residence, formerly called Lambton Lodge and now called George Brown House, at 186 Beverley Street in Toronto, was named a National Historic Site of Canada in 1974. It is now operated by the Ontario Heritage Trust as a conference centre and offices.[22]

Brown also maintained an estate, Bow Park, near Brantford, Ontario. Bought in 1826, it was a cattle farm during Brown's time and is currently a seed farm.[23]

Toronto's George Brown College (founded 1967) is named after him.[24] A statue of George Brown can be found on the front west lawn of Queen's Park[25] and another on Parliament Hill in Ottawa (sculpted by George William Hill in 1913).[26]

Brown married Anne Nelson (d. 1906) in 1862 and had three children. After his death, Anne and the children moved to her hometown of Edinburgh in Scotland, where one of his sons, George Mackenzie Brown (1869–1946), became a Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom, representing Edinburgh Central.[27][28]

He was portrayed by Peter Outerbridge in the 2011 CBC Television film John A.: Birth of a Country.[29]

George Brown appears on a Canadian postage stamp issued on August 21, 1968.[30]

References

- "BROWN, The Hon. George". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- Careless, J.M.S. (1972). "BROWN, GEORGE". In Hayne, David (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. X (1871–1880) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- Baker, Nathan (February 13, 2018). "Anti-Slavery Society of Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Careless, Brown of the Globe 1:172-74

- Waite, P. B. (2001). The Life and Times of Confederation 1864-1867 (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 98–99.

- Gwyn, Richard (2009). John A: The Man Who Made Us. Toronto: Random House Canada. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-3073-7135-5. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

What has French-Canadianism been denied? Nothing. It bars all it dislikes – it extorts all its demands – and it grows insolent over its victories. Letter from George Brown

- Careless, JMS (1967). The Union of the Canadas. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Ltd.

- Moore, Christopher (1997). 1867: How the Fathers Made a Deal. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-1-5519-9483-3.

- Brown Papers, George Brown to Anne Brown, October 15, 1864.

- Careless, J.M.S. (1996). "George Brown and the Mother of Confederation". Careless at Work: Selected Canadian historical studies. Toronto: Dundurn. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4597-1340-6.

- Careless, J.M.S. (1960). George Brown and the Mother of Confederation. Report of the Annual Meeting. Canadian Historical Association. p. 71.

- Gwyn (2009), p. 319

- Waite (2001), p. 113

- Waite (2001), p. 139

- "George Brown on Confederation". The Quebec History Encyclopedia. Marianopolis College. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- Waite (2001), p. 140

- Gwyn (2009), p. 330

- Carlyle, Edward Irving (1901). . Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Sally Zerker, "George Brown and the Printers Union," Journal of Canadian Studies (1975) 10#1 pp 42-48.

- "Historicist: The Assassination of George Brown". Torontoist. May 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2009..

- Gray, Jeff (October 21, 2016). "Park to be named after William Peyton Hubbard, the first black person elected to Toronto city council". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "George Brown House (Toronto)". Ontario Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- Bow Farms Archived January 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "History". George Brown College. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "George Brown Statue, 1884". Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Explore the statues, monuments and memorials of the Hill". Public Works and Government Services Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Skikavich, Julia (July 7, 2015). "Anne Brown". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Mr George Brown (Hansard)". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Weekes, Renee (September 15, 2011). "John A: Birth of a Country – Two-Hour Political Thriller Airs on CBC Television Monday, September 19 at 8:00 p.m. (8:30 p.m. NT)" (Press release). Veritas Canada. Retrieved November 27, 2018 – via Cision.

- "OTD: George Brown co-founds Anti-Slavery Society of Canada". Canadian Stamp News. February 26, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

Further reading

- Bélanger, Claude. "George Brown", in L’Encyclopédie de l’histoire du Québec / The Quebec History Encyclopedia. (Marianopolis College, March 2006) online

- Careless, J.M.C. Brown of the Globe: Volume One: Voice of Upper Canada 1818-1859 (1959) online

- Careless, J.M.C. Brown of the Globe: Volume Two: Statesman of Confederation 1860-1880. (Vol. 2. Dundurn, 1996) excerpt

- Careless, J. M. S. "BROWN, GEORGE," in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 18, 2015, online

- Careless, J.M.C. "George Brown and Confederation," Manitoba Historical Society Transactions, Series 3, Number 26, 1969-70 online

- Caron, Jean-François. George Brown: la Confédération et la dualité nationale, Québec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 2017.

- Creighton, Donald G. "George Brown, Sir John Macdonald, and the "Workingman"." Canadian Historical Review (1943) 24#4 pp: 362-376.

- Gauvreau, Michael. "Reluctant Voluntaries: Peter and George Brown: The Scottish Disruption and the Politics of Church and State in Canada." Journal of religious history 25.2 (2001): 134-157.

- Mackenzie, Alexander. The life and speeches of Hon. George Brown (Toronto, Globe, 1882)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Brown (politician born 1818). |

- Meet the Browns: A Confederation Family, online exhibit on Archives of Ontario website

- George Brown family fonds, Archives of Ontario

- George Brown – Parliament of Canada biography

- A website for an upcoming documentary film on George Brown

- George Brown at Project Gutenberg (Biography by John Lewis)

- George Brown at Find a Grave

- Photograph: Hon. George Brown in 1865. McCord Museum

- Photograph: Hon. George Brown in 1865. McCord Museum

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir John A. Macdonald |

Joint Premiers of the Province of Canada – Canada West August 2–6, 1858 |

Succeeded by Sir John A. Macdonald |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by none |

Leader of the Liberal Party of Canada West/Ontario Liberal Party 1857–1873 |

Succeeded by Archibald McKellar |

| Preceded by Robert Baldwin as Reformer Leader |

Leader of the Liberal Party of Canada unofficial 1857–1873 |

Succeeded by Alexander Mackenzie |