Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip (Serbian Cyrillic: Гаврило Принцип, pronounced [ɡǎʋrilo prǐntsiːp]; 25 July 1894 – 28 April 1918) was a Bosnian Serb member of Young Bosnia who sought an end to Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the age of 19, he assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and the Archduke's wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Princip and his accomplices were arrested and implicated as a nationalist secret society, which initiated the July Crisis and led to the outbreak of World War I.

Gavrilo Princip | |

|---|---|

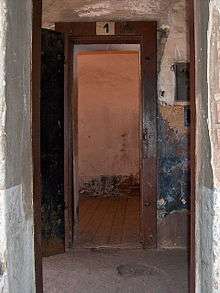

.jpg) Gavrilo Princip in his prison cell at the Terezín fortress | |

| Born | 25 July 1894 |

| Died | 28 April 1918 (aged 23) |

| Resting place | Vidovdan Heroes Chapel, Sarajevo 43°52′0.76″N 18°24′38.88″E |

| Known for | The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which contributed to the outbreak of World War I |

| Signature | |

| |

At his trial, Princip stated that: "I am a Yugoslav nationalist, aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs, and I do not care what form of state, but it must be freed from Austria."[1] Princip was sentenced to twenty years in prison, the maximum for his age, and was imprisoned at the Terezín fortress. He died on 28 April 1918 from tuberculosis exacerbated by poor prison conditions which had already caused the loss of his right arm.

Early life

Gavrilo Princip was born in the remote hamlet of Obljaj, near Bosansko Grahovo, on 25 July [O.S. 13 July] 1894. He was the second of his parents' nine children, six of whom died in infancy. Princip's mother Marija wanted to name him after her late brother Špiro, but he was named Gavrilo at the insistence of a local Eastern Orthodox priest, who claimed that naming the sickly infant after the Archangel Gabriel would help him survive.[2]

A Serb family, the Princips had lived in northwestern Bosnia for many centuries[3] and adhered to the Serbian Orthodox Christian faith.[4] Princip's parents, Petar and Marija (née Mićić), were poor farmers who lived off the little land that they owned.[5] They belonged to a class of Christian peasants known as kmeti (serfs), who were often oppressed by their Muslim landlords.[6]

Petar, who insisted on "strict correctness," never drank or swore and was ridiculed by his neighbours as a result.[5] In his youth, he fought in the Herzegovina Uprising against the Ottoman Empire.[7] Following the revolt, he returned to being a farmer in the Grahovo valley, where he worked approximately 4 acres (1.6 ha; 0.0063 sq mi) of land and was forced to give a third of his income to his landlord. In order to supplement his income and feed his family, he resorted to transporting mail and passengers across the mountains between northwestern Bosnia and Dalmatia.[8]

Despite Petar's opposition, Gavrilo Princip began attending primary school in 1903, aged nine. He overcame a difficult first year and became very successful in his studies, for which he was awarded a collection of Serbian epic poetry by his headmaster.[7] At the age of 13, Princip moved to Sarajevo, where his elder brother Jovan intended to enroll him into an Austro-Hungarian military school.[7] However, by the time Princip reached Sarajevo, Jovan had changed his mind after a friend advised him not to make Gavrilo "an executioner of his own people." Princip was enrolled into a merchant school instead.[9] Jovan paid for his tuition with the money he earned performing manual labour, carrying logs from the forests surrounding Sarajevo to mills within the city.[10] After three years of study, Gavrilo transferred to a local gymnasium.[9] In 1910, he came to revere Bogdan Žerajić, a Bosnian Serb revolutionary who attempted to assassinate Marijan Varešanin, the Austro-Hungarian Governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, before taking his own life.[10] In 1911, Princip joined Young Bosnia (Serbian: Mlada Bosna), a society that wanted to separate Bosnia from Austria-Hungary and unite it with the neighbouring Kingdom of Serbia.[9] Because the local authorities had forbidden students to form organizations and clubs, Princip and other members of Young Bosnia met in secret. During their meetings, they discussed literature, ethics and politics.[10]

In 1912, Princip was expelled from school for being involved in a demonstration against Austro-Hungarian authorities.[7] A student who witnessed the incident claimed that "Princip went from class to class, threatening with his knuckle-duster all the boys who wavered in coming to the new demonstrations."[11] Princip left Sarajevo shortly after being expelled and made the 280-kilometre (170 mi) journey to Belgrade on foot. According to one account, he fell to his knees and kissed the ground upon crossing the border into Serbia. In Belgrade, Princip volunteered to join the Serbian guerrilla bands fighting the Ottoman Turks, under the leadership of Major Vojislav Tankosić.[12] Tankosić was a member of the Black Hand, the foremost conspiratorial society in Serbia at the time.[9]

At first, Princip was rejected at a recruitment office in Belgrade because of his small stature. Enraged, he tracked down Tankosić himself, who also told him that he was too small and weak.[13] Humiliated, Princip returned to Bosnia and lodged with his brother in Sarajevo. He spent the next several months moving back and forth between Sarajevo and Belgrade. In Belgrade he met Živojin Rafajlović, one of the founders of the Serbian Chetnik Organization, who sent him (along with 15 other Young Bosnia members) to the Chetnik training centre in Vranje.[14] There, they met with school manager Mihajlo Stevanović-Cupara. He lived in Cupara's house, which is today located on Gavrilo Princip Street in Vranje. Princip practiced shooting, using bombs and the blade, after which training was completed and he returned to Belgrade.[15]

In 1913, while Princip was staying in Sarajevo, Austria-Hungary declared a state of emergency, implemented martial law, seized control of all schools, and prohibited all Serb cultural organizations.[12]

Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

.jpg)

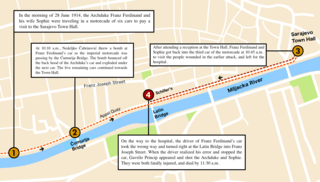

On 28 June 1914, Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, Duchess Sophie Chotek. The royal couple arrived in Sarajevo by train shortly before 10 a.m. and rode in the third car of a six-car motorcade towards Town Hall.[16] Their car's top was rolled back in order to allow the crowds a good view of its occupants.[17]

Princip and the five other conspirators lined the route. They were spaced out along the Appel Quay, each one with instructions to assassinate the Archduke when the royal car reached their position. The first conspirator on the route to see the royal car was Muhamed Mehmedbašić. Standing by the Austro-Hungarian Bank, Mehmedbašić lost his nerve and allowed the car to pass without taking action. At 10:15 a.m., when the motorcade passed the central police station, nineteen-year-old student Nedeljko Čabrinović hurled a hand grenade at the Archduke's car. The driver accelerated when he saw the object flying towards him, and the bomb, which had a 10-second delay, exploded under the fourth car. Two of the occupants were seriously wounded.[18] After Čabrinović's failed attempt, the motorcade sped away and Princip and the remaining conspirators failed to act due to the motorcade's high speed.[19]

After the Archduke gave his scheduled speech at Town Hall, he decided to visit the victims of Čabrinović's grenade attack at the Sarajevo Hospital.[20] In order to avoid the city centre, General Oskar Potiorek decided that the royal car should travel straight along the Appel Quay to the hospital. However, Potiorek forgot to inform the driver, Leopold Lojka, about this decision.[20] On the way to the hospital, Lojka incorrectly turned onto a side street where Princip had positioned himself in front of a local delicatessen. After realizing his mistake, Lojka braked and began to reverse. As he did so the engine stalled and the gears locked. Princip stepped forward, drew his FN Model 1910,[21][22] and at point-blank range fired twice into the car, first hitting the Archduke in the neck, and then hitting the Duchess in the abdomen.[23][24] They both died shortly after.[24]

Arrest and trial

Princip attempted to shoot himself, but the pistol was wrestled from his hand before he had a chance to fire another shot.[25] At his trial, he said he regretted the killing of the Duchess and meant to kill Potiorek, but was nonetheless proud of what he had done.[26][27] He further stated that: "I am a Yugoslav nationalist, aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs, and I do not care what form of state, but it must be freed from Austria."[1] The Black Hand was implicated in the assassination which led Austria-Hungary to issue a démarche to Serbia known as the July Ultimatum which led up to the outbreak of World War I.[28]

Princip was nineteen years old at the time and too young to receive the death penalty, as he was twenty-seven days shy of the twenty-year minimum age limit required by Habsburg Law.[29] Instead, he received the maximum sentence of twenty years in prison.[30]

Imprisonment and death

Princip was chained to a wall in solitary confinement at the Terezín fortress, where he lived in harsh conditions and suffered from tuberculosis.[31][28] The disease ate away his bones so badly that his right arm had to be amputated.[29] In January 1916, Princip unsuccessfully attempted to hang himself with a towel.[32] From February to June 1916, Princip met with Martin Pappenheim, a psychiatrist in the Austro-Hungarian army, four times.[32] Pappenheim wrote that Princip believed the World War was bound to happen, independent of his actions, and that he "cannot feel himself responsible for the catastrophe."[31]

Gavrilo Princip died on 28 April 1918, three years and ten months after the assassination. At the time of his death, weakened by malnutrition and disease, he weighed around 40 kilograms (88 lb; 6 st 4 lb).[33][34]

Fearing his bones might become relics for Slavic nationalists, Princip's prison guards secretly took the body to an unmarked grave, but a Czech soldier assigned to the burial remembered the location, and in 1920 Princip and the other "Heroes of Vidovdan" were exhumed and brought to Sarajevo, where they were buried together beneath the Vidovdan Heroes Chapel "built to commemorate for eternity our Serb heroes" at the Holy Archangels Cemetery[35] which includes a citation from the Montenegrin poet Njegoš: "Blessed is he who lives forever. He had something to be born for."[36]

Legacy

Princip's legacy is still disputed. He is celebrated as a hero by Serbs but regarded as a terrorist by many Bosniaks.[37][38]

In socialist Yugoslavia, Gavrilo Princip was venerated as a national hero and a freedom fighter who fought to liberate all the peoples of Yugoslavia from Austrian rule;[39] however, in the modern day, many Croats and Bosniaks have now expressed viewpoints characterizing Princip as a murderer.[39] Asim Sarajlic, a senior MP of the Bosniak nationalist Party of Democratic Action, stated that Princip brought an end to "a golden era of history under Austrian rule" and that "we are strongly against the mythology of Princip as a fighter of freedom."[39]

However, Serbs continue to venerate his memory, with Nenad Samardžija, governor of East Sarajevo, saying that the assassination was not a terrorist act but "a movement of young people who wanted to liberate themselves from colonial slavery."[40] During the Yugoslavian era, Latin Bridge, the site of the assassination, was renamed Princip's Bridge in remembrance.[41][42]

Memorials and commemoration

The house where Princip lived in Sarajevo was destroyed during World War I. After the war, it was rebuilt as a museum in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia was conquered by Germany in 1941 and Sarajevo became part of the Independent State of Croatia. The Croatian Ustaše destroyed the house again. After the establishment of Communist Yugoslavia in 1944, the house of Gavrilo Princip became a museum again and there was another museum dedicated to him within the city of Sarajevo.[36] During the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, the house of Gavrilo Princip was destroyed and then rebuilt for the third time in 2015.[43]

Princip's pistol was confiscated by the authorities and eventually given, along with the Archduke's bloody undershirt, to Anton Puntigam, a Jesuit priest who was a close friend of the Archduke and had given the Archduke and his wife their last rites. The pistol and shirt remained in the possession of the Austrian Jesuits until they were offered on long-term loan to the Museum of Military History in Vienna in 2004. It is now part of the permanent exhibition there.[44]

There have been many short-lived memorials to Gavrilo Princip.[45] In 1917, a pillar was constructed at the corner of where the assassination took place. It was destroyed the following year.[45] In the 1940s, a plaque commemorating Princip was removed when the German Army invaded,[45] and after World War II, a new plaque went up which incorrectly claimed that "Gavrilo Princip threw off the German occupiers."[45] During the Bosnian War, embossed footprints marking where Princip fired the fatal shots were torn out.[45]

As the centenary of the assassination neared, a plaque at the corner where the assassination took place was put up, which states: "From this place on 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia."[45][46] On 21 April 2014, a bust of Princip was unveiled in Tovariševo,[47] and on the centenary itself, a statue was erected in East Sarajevo.[48][49]

A year later, a statue of Princip was unveiled in Belgrade by the President of Serbia Tomislav Nikolić and the President of Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik, as a gift from Republika Srpska to Serbia.[50] At the unveiling Nikolić gave a speech, saying in part: "Princip was a hero, a symbol of liberation ideas, tyrant-murderer, idea-holder of liberation from slavery, which spanned through Europe."[50]

See also

References

- Dedijer 1966, p. 341.

- Dedijer 1966, pp. 187–188.

- Fromkin 2007, pp. 121–122.

- Roider 2005, p. 935.

- Fabijančić 2010, p. xxii.

- Schlesser 2005, p. 93.

- Kidner et al. 2013, p. 756.

- Schlesser 2005, p. 95.

- Roider 2005, p. 936.

- Schlesser 2005, p. 96.

- Malcolm 1994, p. 154.

- Schlesser 2005, p. 97.

- Glenny 2012.

- Documentary History of the War. 2. London: Printing House Square. 1917. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Irić, Radoman (2 October 2013). "Ovde je Gavrilo Princip učio da puca " [This is where Gavrilo Princip learnt to shoot]. Blic (in Serbian). Belgrade. p. 21. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Burns, Tracy. "June 28, 1914: The first attempt". www.private-prague-guide.com/. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Donnelley 2012, p. 33.

- Dedijer 1966, ch. XIV, footnote 21.

- Dedijer 1966, p. 15.

- Shapiro, Ari (27 June 2014). "A Century Ago In Sarajevo: A Plot, A Farce And A Fateful Shot". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Manfried Rauchensteiner, Manfred Litscher (ed.): Das Heeresgeschichtliche Museum in Wien. [Museum of Military History in Vienna] Graz, Wien 2000, page 63.

- Belfield 2011, p. 241.

- Greenspan, Jesse. "The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, 100 Years Ago". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Remak 1959, pp. 137–142.

- Duffy, Michael (22 August 2009). "Who's Who – Gavrilo Princip". www.firstworldwar.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Man accused of murdering Archduke Ferdinand goes on trial – archive, 1914". The Guardian. 17 October 2017. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Dedijer 1966, p. 346.

- Johnson 1989, pp. 52–54.

- Butcher, Tim (30 August 2013). "The man who started the First World War". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Butcher, Tim (29 June 2014). "The man who started WWI: 7 things you didn't know". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Gavrilo Princip Speaks: 1916 Conversations with Martin Pappenheim | Carl Savich". 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Pappenheim, Martin (1916). "Gavrilo Princip, a participant in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand". The British Library. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "101st Anniversary of the Sarajevo Assassination that caused the World War I". Sarajevo Times. 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- DeVoss, David. "Searching for Gavrilo Princip" (PDF). Smithsonian Magazine. August 2000: 42–53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2004.

- Pokop.ba. "Sveti Arhangeli Georgije i Gavrilo" (in Bosnian). Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- "GAVRILO PRINCIP – SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE". Meet the Slavs. 29 June 2014. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Beasley-Murray, Benjamin (26 June 2014). "Gavrilo Princip's Legacy Still Contested". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "Gavrilo Princip: hero or villain?". The Guardian. 6 May 2014. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019.

- MacDowall, Andrew (27 June 2014). "Villain or hero? Sarajevo is split on archduke's assassin Gavrilo Princip". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Matt Robinson; Daria Sito-Sucic (11 March 2004). "An assassin divides his native Bosnia 100 years on". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Slobodan G. Markovich. "Anglo-American Views of Gavrilo Princip" (PDF). Balcanica XLVI (2015). p. 298. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2017 – via Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Maja Slijepčević (October 2016). "From the Monument of Assassination Towards Gavrilo Princip's Monuments" (PDF). Heritage of the First World War: Representations and Reinterpretations (International Symposium). p. 71. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2020 – via University of Ljubljana.

- Rodna kuća Gavrila Principa: Obnovljena i zaboravljena Archived 10 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine (in Serbian)

- Connolly, Kate (22 June 2004). "Found: the gun that shook the world". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- Shapiro, Ari (27 June 2014). "The Shifting Legacy Of The Man Who Shot Franz Ferdinand". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Kuper, Simon (21 March 2014). "Sarajevo: the crossroads of history". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "DA SE NE ZABORAVI: Meštani Tovariševa sami podigli spomenik Principu!" [NOT FORGETTING: villagers themselves erected a monument to Princip!]. Telegraf. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Monument to Gavrilo Princip unveiled in East Sarajevo Archived 22 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, B92, 27 June 2014 (retrieved 22 June 2015).

- Serbia: Belgrade's monument to Franz Ferdinand assassin Archived 3 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 8 June 2015 (retrieved 22 June 2015).

- "Ne dozvoljavam vređanje poklanih Srba" [I do not allow insults to slaughtered Serbs]. B92. 28 June 2015. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

Bibliography

- Belfield, Richard (2011). A Brief History of Hitmen and Assassinations. Constable & Robinson, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-849018-05-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Christopher (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06219-922-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1966). The Road to Sarajevo. Simon and Schuster. ASIN B0007DMDI2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donnelley, Paul (2012). Assassination!. ISBN 978-1-908963-03-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fabijančić, Tony (2010). Bosnia: In the Footsteps of Gavrilo Princip. Edmonton: University of Alberta. ISBN 978-0-88864-519-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fromkin, David (2007). Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-42578-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilbert, Martin (1995). The First World War. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-637666-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–2012: New and Updated (revised ed.). Penguin. ISBN 978-1-77089-274-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, Lonnie (1989). Introducing Austria: A short history. ISBN 0-929497-03-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kidner, Frank; Bucur, Maria; Mathisen, Ralph; McKee, Sally; Weeks, Theodore (2013). Making Europe: The Story of the West Since 1550. 2 (2th ed.). Boston: Wadsworth Cengage. ISBN 978-1-111-84134-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malcolm, Noel (1994). Bosnia: A Short History. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5520-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Remak, Joachim (1959). Sarajevo: The Story of a Political Murder. Criterion. ASIN B001L4NB5U.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roider, Karl (2005). "Princip, Gavrilo (1894–1918)". In Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (eds.). The Encyclopedia of World War I : A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schlesser, Steven (2005). The Soldier, the Builder & the Diplomat. Seattle: Cune Press. ISBN 978-1-885942-07-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stokesbury, James (1981). A Short History of World War I. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-061763-61-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 978-2-8251-1958-7.

- Brescia, Anthony M (1965). The Role Gavrilo Princip in the Greater Serbian Movement.

- Butcher, Tim (2014). The Trigger: Hunting the Assassin who Brought the World to War. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-8793-4.

- Ljubibratić, Dragoslav (1959). Gavrilo Princip. Nolit.

- Savary, Michèle (2004). Sarajevo 1914: vie et mort de Gavrilo Princip. L'AGE D'HOMME. ISBN 978-2-8251-1891-7.

- Villiers, Peter (2010). Gavrila Princip: The Assassin Who Started the First World War. Unknown Publisher. ISBN 978-0-9566211-0-8.

- Wolfson, Robert; Laver, John (30 December 2001). Years of Change, European History 1890–1990 (3 ed.). Hodder Murray. p. 117. ISBN 0-340-77526-2.

- Gavrilo Princips Bekenntnisse. Zwei Manuscripte Princips, Aufzeichungen Seines Gefängnispsychiaters Dr. Pappenheim Aus Gesprächen Von Feber ... Über Das Attentat, Princips Leben und Seine Politischen und Sozialen Anschauungen. Mit Einführung und Kommentar Von R.P. Wien: Lechner und Son. 1926.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gavrilo Princip. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gavrilo Princip |