Gates of Alexander

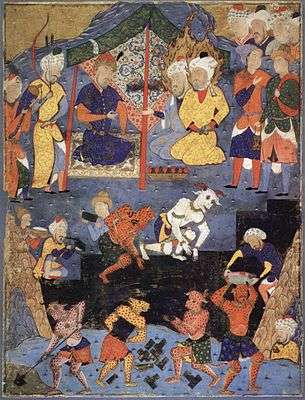

The Gates of Alexander was a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog[1]) from invading the land to the south. The gates were a popular subject in medieval travel literature, starting with the Alexander Romance in a version from perhaps the 7th century.

The wall, also known as the Caspian Gates, has been identified with two locations: the Pass of Derbent, Russia, or with the Pass of Dariel, a gorge forming a pass between Russia and Georgia with the Caspian Sea to the east. Tradition also connects it to the Great Wall of Gorgan (Red Snake) on its south-eastern shore.

These fortifications were historically part of the defence lines built by the Sasanians of Persia, while the Great Wall of Gorgan may have been built by the Parthians.

A similar story about such wall is mentioned on al-Kahf ("The Cave"), the 18th chapter of Quran. According to this narrative, Gog and Magog (Arabic: يأجوج ومأجوج Yaʾjūj wa-Maʾjūj) were walled off by Dhul-Qarnayn (possessor of the Two Horns), a righteous ruler and conqueror who reached the farthest point of the Earth. The barrier was constructed with melted iron sheets like red flames.[2]

Literary background

The name Caspian Gates originally applied to the narrow region at the southeast corner of the Caspian Sea, through which Alexander actually marched in the pursuit of Bessus, although he did not stop to fortify it. It was transferred to the passes through the Caucasus, on the other side of the Caspian, by the more fanciful historians of Alexander.

Josephus, a Jewish historian in the 1st century, is known to have written of Alexander's gates, designed to be a barrier against the Scythians. According to this historian, the people whom the Greeks called Scythians were known (among the Jews) as Magogites, descendants of Magog in the Hebrew Bible. These references occur in two different works. The Jewish War states that the iron gates Alexander erected were controlled by the king of Hyrcania (on the south edge of the Caspian), and allowing passage of the gates to the Alans (whom Josephus considered a Scythic tribe) resulted in the sack of Media. Josephus's Antiquities of the Jews contains two relevant passages, one giving the ancestry of Scythians as descendants of Magog son of Japheth, and another that refers to the Caspian Gates being breached by Scythians allied to Tiberius during the Armenian War.[lower-alpha 1][3]

The Gates are also mentioned in Procopius' History of the Wars: Book I. Here they are mentioned as the Caspian Gates and they are a source of diplomatic conflict between the Byzantines and the Sassanid Persians. When the current holder of the gates passes away, he bequeaths it to Emperor Anastasius. Anatasius, unable and unwilling to finance a garrison for the gates, loses them in an assault by the Sassanid King Cabades (Kavadh I). After peace, Anastasius builds the city of Dara, which would be a focus point for war during the reign of Justinian and site of the Battle of Dara. In this war, the Persians once again bring up the gates during negotiations, mentioning that they block the pass to the Huns for the benefit of both Persians and Byzantines and deserve to be compensated for their service[4].

The Gates occur in later versions of the Alexander Romance of Pseudo-Callisthenes, in the interpolated chapter on the "Unclean Nations" (8th century). This version locates the gates between two mountains called the "Breasts of the North" (Greek: Μαζοί Βορρά[5]). The mountains are initially 18 feet apart and the pass is rather wide, but Alexander's prayers to God causes the mountains to draw nearer, thus narrowing the pass. There he builds the Caspian Gates out of bronze, coating them with fast-sticking oil. The gates enclosed twenty-two nations and their monarchs, including Goth and Magoth (Gog and Magog). The geographic location of these mountains is rather vague, described as a 50-day march away northwards after Alexander put to flight his Belsyrian enemies (the Bebrykes,[6] of Bithynia in modern-day North Turkey).[7][8]

A similar story also appears in the Qur'an, Surat al-Kahf 83–98. The Qur'an describes a figure known as Dhul Qarnayn, widely believed to be Alexander the Great, who built a wall made of iron between two mountains to defend the people from Yajuj and Majuj.[9]

During the Middle Ages, the Gates of Alexander story was included in travel literature such as the Travels of Marco Polo and the Travels of Sir John Mandeville. The identities of the nations trapped behind the wall are not always consistent, however; Mandeville claims Gog and Magog are really the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, who will emerge from their prison during the End Times and unite with their fellow Jews to attack the Christians. Polo speaks of Alexander's Iron Gates, but says the Comanians are the ones trapped behind it. He does mention Gog and Magog, however, locating them north of Cathay. Some scholars have taken this as an oblique and confused reference to the Great Wall of China, which he does not mention otherwise. The Gates of Alexander may represent an attempt by Westerners to explain stories from China of a great king building a great wall. Knowledge of Chinese innovations such as the compass and south-pointing chariot is known to have been diffused (and confused) across Eurasian trade routes.

The medieval German legend of the Red Jews was partially based on stories of the Gates of Alexander. The legend disappeared before the 17th century.

Geographical identifications

(

It is not clear which precise location Josephus meant when he described the Caspian gates. It may have been the Gates of Derbent (lying due east, nearer to Persia), or it may have been the Darial Gorge, lying west, bordering Iberia, located between present-day Ingushetia and Georgia.

However, neither of these were within Hyrcania, but lay to the north and west of its boundaries. Another suggestion is some mountain pass in the Taurus-Zagros Mountains, somewhere near Rhaegae, Iran, in the heart of Hyrcania.[10]

Derbent

The Gates of Alexander are most commonly identified with the Caspian Gates of Derbent, whose thirty north-looking towers used to stretch for forty kilometers between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus Mountains, effectively blocking the passage across the Caucasus.

Derbent was built around a Sassanid Persian fortress, which served as a strategic location protecting the empire from attacks by the Gokturks. The historical Caspian Gates were not built until probably the reign of Khosrau I in the 6th century, long after Alexander's time, but they came to be credited to him in the passing centuries. The immense wall had a height of up to twenty meters and a thickness of about 10 feet (3 m) when it was in use.

Darial

The Pass of Dariel or Darial has also been known as the "Gates of Alexander" and is a strong candidate for the identity of the Caspian Gates.[11]

Wall of Gorgan

An alternative theory links the Caspian Gates to the so-called "Alexander's Wall" (the Great Wall of Gorgan) on the south-eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, 180 km of which is still preserved today, albeit in a very poor state of repair.[12]

The Great Wall of Gorgan was built during the Parthian dynasty simultaneously with the construction of the Great Wall of China and it was restored during the Sassanid era (3rd–7th centuries)[13]

See also

- Alexander in the Qur'an

- Cyrus the Great in the Qur'an

- Cilician Gates

- Iron Gate (Central Asia)

Notes

- Explanatory notes

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 1.123 and 18.97; The Jewish War 7.244-51

- Citations

- Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius 8; Alexander Romance, epsilon recension 39.

- Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. 57, fn 3.

- Bietenholz 1994, p. 122.

- History of the Wars Books I and II https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16764/16764-h/16764-h.htm

- Anderson 1932, p. 37.

- Anderson 1932, p. 35.

- Stoneman, Richard (tr.), ed. (1991), The Greek Alexander Romance, Penguin, pp. 185–187

- Anderson (1932), p. 11.

- Dathorne, O. R. (1994). Imagining the World: Mythical Belief Versus Reality in Global Encounters. Greenwood. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0897893646. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 11.

- Anderson (1932), p. 15–20.

- Kleiber 2006

- Omrani Rekavandi, H., Sauer, E., Wilkinson, T. & Nokandeh, J. (2008), The enigma of the red snake: revealing one of the world’s greatest frontier walls, Current World Archaeology, No. 27, February/March 2008, pp. 12–22. PDF 5.3 MB. p. 13

References

- Anderson, Andrew Runni (1932), Alexander's Gate, Gog and Magog: And the Inclosed Nations, p. 11

- Bietenholz, Peter G. (1994). Historia and fabula: myths and legends in historical thought from antiquity to the modern age. Brill. ISBN 9004100636.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Artamonov, Mikhail. "Ancient Derbent" (Древний Дербент). in: Soviet Archaeology, №8, 1946.

- Kleiber, Katarzyna (July 2006). "Alexander's Caspian Wall – A Turning-Point in Parthian and Sasanian Military Architecture?". Folia Orientalia. 42/43: 173–95.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Donzel, Emeri J.; Schmidt, Andrea Barbara (2010). Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources: Sallam's Quest for Alexander's Wall. Brill. ISBN 9004174168.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)