French occupation of Moscow

The Occupation of Moscow by the Great Army[K 1] under the command of the Emperor Napoleon lasted a little more than a month, from September 14 to October 20, 1812, and became a turning point in the Patriotic War of 1812. During the occupation, the city was looted and devastated by fire, the causes of which are controversial among historians. The last time before this, Moscow was occupied by foreign troops exactly 200 years before.

Background

After the Battle of Borodino, in which the Russian army suffered heavy losses, Commander-in-Chief Kutuzov ordered on September 8, 1812, to retreat towards Moscow to Mozhaysk with the firm intention to save the army.

On the afternoon of September 13, 1812, a military council was held in the village of Fili, near Moscow, on a plan for further action. Despite the fact that the majority of generals, primarily General Bennigsen, spoke out in favor of giving Napoleon a new general battle near the walls of Moscow, Kutuzov, on the basis of the main task of preserving the army, interrupted the meeting of the military council and ordered to retreat, surrendering Moscow to the French.

Having estimated the difficult and dangerous situation of the Russian army stretched across Moscow, burdened with a large number of wounded and numerous convoys, and also not having the ability to hold the enemy for a long time on its approaches, the commander of the Russian rearguard infantry general Mikhail Miloradovich decided to enter into negotiations with the commander of the French vanguard, Marshal Joachim Murat. To this end, Miloradovich sent to Murat the captain of the Life Guards of the Hussar Regiment, Fyodor Akinfov, with a note signed by the duty general of the General Staff of the Russian Army, Colonel Paisiy Kaysarov, which said: "The wounded left in Moscow are entrusted to the humanity of the French troops".[1] In words, Miloradovich ordered on his behalf to convey to Murat that[2][3]

If the French want to occupy Moscow as a whole, they must, without advancing strongly, let us calmly leave it with artillery and a convoy; otherwise, General Miloradovich will fight to the last man before Moscow and in Moscow and, instead of Moscow, will leave the ruins.

Akinfov's task also included staying in the enemy's camp for as long as possible to gain time.[2][3]

On the morning of September 14, Akinfov, with a trumpeter from Miloradovich's convoy, drove up to the enemy forward chain just at the time when the shooting had resumed and Murat had already ordered his cavalry to attack the Russian positions.[4] Colonel of the 1st Horse-Jaeger Regiment, Clément Louis Elyon de Villeneuve, who went into the chain at the signal of a trumpeter, sent Akinfov to the commander of the 2nd Cavalry Corps, General Horace François Bastien Sébastiani. The latter himself proposed to transmit the letter to Murat, but Akinfov said that he was instructed not only to personally deliver the letter to the Neapolitan King, but also to convey something to him in words. Then Sebastiani nevertheless ordered to send the Russian parliamentarians to Murat.[3]

After reading the note, Murat objected: "In vain to entrust the sick and wounded to the generosity of the French troops; the French in captive enemies no longer see enemies".[5][6] In response to the demand of Miloradovich, he said that the offensive could be stopped only after the appropriate order of Napoleon himself, after which he instructed his adjutant to conduct Akinfov to the French emperor. However, when Akinfov and the trumpeter traveled about 200 steps, Murat unexpectedly ordered the Russian parliamentarians to be returned and told Akinfov that "wanting to save Moscow" he would accept Miloradovich's conditions and would advance "as quietly" as the Russians, but with the condition that French troops could take the city on the same day. In addition, during the dialogue, Murat asked Akinfov, as a native of Moscow, to persuade the residents of the city to remain calm, ensuring that they would not be harmed and not taken the slightest indemnity.[2][3]

The Great Army began to enter Moscow on September 14 in the afternoon, essentially following the heels of the Russian army leaving it. It happened that cavalry from the French vanguard mixed with the Cossacks of the Russian rearguard, while not only not showing hostile relations to each other, but also sometimes showing mutual respect.[7]

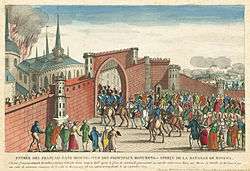

Entrance of the French to Moscow

On September 14, 1812, at 2 pm on Tuesday, Napoleon arrived at Poklonnaya Gora, which was 3 miles away from Moscow (within its borders for 1812).[K 2] There, by order of the Neapolitan King Murat, the vanguard of the French troops were formed into battle formation. Here Napoleon waited for half an hour, and then, not seeing any enemy action from Moscow, ordered a shot from a cannon to give a signal to the further movement of the French troops to Moscow. Cavalry and artillery on horses galloped at full speed, and the infantry ran. After reaching about a quarter-hour of the Dorogomilovskaya outpost, Napoleon dismounted at the Kamer-Kollezhsky shaft and began to pace back and forth, waiting for a delegation or bringing of city keys from Moscow. Infantry and artillery to the music began to enter the city.

After about ten minutes of waiting, a young man in a blue overcoat and a round hat approached Napoleon and, after talking with Napoleon for a few minutes, entered the outpost. According to an eyewitness Fyodor Korbaletsky, this young man told the French emperor that the Russian army and residents left the city. This news, spread among the French, at first aroused bewilderment in them, which over time grew into despondency and grief. Napoleon was out of balance.

At that time, suitable French troops began to split before approaching the Dorogomilovskaya outpost into two parts and bypass Moscow along the Kamer-Kollezhsky shaft to the right and left to enter the city through other outposts.

An hour later, having regained consciousness, Napoleon mounted his horse and rode into Moscow. He was followed by cavalry, which had not entered Moscow before. Having passed the Dorogomilovskaya Yamskaya Sloboda and reaching the banks of the Moscow River, Napoleon stopped. At this time, the vanguard crossed the Moscow River, infantry and artillery began to cross the river over the bridge, and the cavalry began to ford. After crossing the river, the army began to break up into small detachments, taking guard on the river bank, along the main streets and side streets of the city.

The streets of the city were deserted. In front of Napoleon, at a distance of a hundred fathoms, two squadrons of horse guards rode. The retinue of Napoleon was very numerous. The difference between the diversity and richness of the decoration of the uniforms of the people surrounding Napoleon and the simplicity of the decoration of the uniform of the emperor himself was striking. On Arbat, Napoleon saw only the owner of the pharmacy with his family and the wounded French general, who was at their stand.

Having reached the Borovitsky gate of the Kremlin, Napoleon, looking at the Kremlin walls, said with a sneer: "What a scary wall!".[8] Ober-Stalmeister Armand de Caulaincourt, who was with the emperor, wrote:[9]

In the Kremlin, just like in most private mansions, everything was in place: even the clock went on, as if the owners remained at home. A city without inhabitants was surrounded by gloomy silence. Throughout our long journey we did not meet a single local resident; the army held positions in the vicinity; some corps were placed in barracks. At three o'clock the emperor mounted his horse, traveled around the Kremlin, was in the Educational Home, visited the two most important bridges and returned to the Kremlin, where he settled in the ceremonial chambers of Emperor Alexander.

Subsequently, as the contemporaries of those events wrote, seeing both the Russian government and the Russian people hatred and self-neglect, who decided to better cede their ancient capital to him than to bow before him, Napoleon ordered that instead of horses, Russians of both sexes should be used to bring edibles to the Kremlin, not analyzing either state or years.[10] According to historian Alexander Martin, Muscovites in general, however, chose not to accept the occupation, but to flee the city. By the beginning of 1812, according to police, there were 270,184 residents in Moscow.[11] According to her report, during the occupation, only about 6,200 civilians remained in the capital, that is, 2.3% of the pre-war population of the city.[12] According to Vladimir Zemtsov in occupied Moscow there were more than 10 thousand inhabitants. In addition, from 10 to 15 thousand Russian wounded and sick soldiers remained in it.[13]

During the occupation, cases of looting by the French army and the local population became more frequent, first caused by a desire to profit (in particular, servants and serfs robbed landlords' homes), and subsequently by a desire to survive in hunger. There were killings by the military of the civilian population. There was practically no rape, since the Muscovites who remained in the city, suffering from hunger, lack of housing and an atmosphere of violence, mostly made contact with the military voluntarily. Actually, the French were often considered by the local population as the least prone to drunkenness and robbery part of the Napoleonic army, in contrast to representatives of other ethnic groups. According to some Muscovites, the French command tried to combat violations of army discipline, although it did not succeed. However, under the influence of government propaganda, which depicted the French as godless, and the news of the desecration of local shrines, the local population sometimes called the French "pagans" or even "basurmans".[14][15]

Moscow Fire

When the French entered Moscow on September 14, 1812, arson was carried out in different places of the city.[16] The French were sure that Moscow was set on fire by order of the Moscow governor – Count Rostopchin.

On the night of September 15 to 16, a strong wind rose, continuing, without weakening, for more than a day. The flames of fire swept the center near the Kremlin, Zamoskvorechye, Solyanka, the fire swept almost simultaneously at the most distant places of the city. The fire[K 3] raged until September 18 and destroyed most of Moscow.

Up to 400 citizens from the lower classes were shot by a French military court on suspicion of arson.

The fire on Napoleon made a gloomy impression. According to an eyewitness,[17] he said: "What a terrible sight! It is they themselves! So many palaces! What an incredible solution! What kind of people! These are Scythians!".

By the night of September 16, the fire intensified so much that Napoleon was forced to leave the Kremlin early in the morning of September 16, having moved to the Petrovsky Palace. Count Ségur wrote:[9]

We were surrounded by a sea of flame; it threatened all the gates leading from the Kremlin. The first attempts to get out of it were unsuccessful. Finally, an exit to the Moscow River was found under the mountain. Napoleon came out through him from the Kremlin with his retinue and the old guard. Coming closer to the fire, we did not dare to enter these waves of the sea of fire. Those who managed to get to know the city a little did not recognize the streets disappearing in smoke and ruins. However, it was necessary to decide on something, because with every moment the fire intensified more and more around us. A strong heat burned our eyes, but we could not close them and had to stare forward. The suffocating air, the hot ashes and the flame of the spiral escaping from everywhere, our breath, short, dry, constrained and suppressed by smoke. We burned our hands, trying to protect our face from the terrible heat, and cast off the sparks that showered and burned the dress.

Napoleon and his entourage drove along the burning Arbat to the Moscow River, then, as Academician Tarle wrote, he moved along a relatively safe route along its shore.

Napoleon's stay in Moscow

On September 18, Napoleon returned to the Kremlin. From Moscow, he continued to manage his empire: he signed decrees, decrees, appointments, movements, awards, and the dismissal of officials and dignitaries. After his return to the Kremlin, the French emperor made the decision, which he announced publicly, to remain in the winter apartments in Moscow, which, as he believed at that time, even in its current state would give him more adapted buildings, more resources and more money, than any other place. He ordered, in accordance with this, to bring the Kremlin and the monasteries surrounding the city into a condition suitable for defense, and also ordered reconnaissance of the surroundings of Moscow to develop a defense system in winter.

To manage the city in the house of Chancellor Nikolai Rumyantsev on Maroseyka 17, a self-government body was opened – the Moscow municipality. Quartermaster Lesseps instructed the local merchant Dulong to select his members from among those remaining in the city of philistinism and merchants. During the 30 days of its activity, a municipality of 25 people was searching for food in the vicinity of the city, helping the poor, saving burning churches. Since the members of the municipality worked in it involuntarily, after Napoleon left the city, almost none of them were punished for collaboration.

To ensure order in the city on October 12, 1812, the French created the municipal police – French: police génèral.

Napoleon himself almost daily traveled around various parts of the city and visited the monasteries surrounding it. Including Napoleon visited the Orphanage and talked with his boss, Major General Tutolmin. At the request of Tutolmin for permission to write a report on the condition of the pupils to the Empress Maria, Napoleon not only allowed, but suddenly added: "I ask you to write to Emperor Alexander, whom I respect as before, that I want peace". On the same day, September 18, Napoleon ordered the official of the Orphanage to go through the French guard posts, with whom Tutolmin sent his report to Saint Petersburg.

In total, Napoleon made three attempts to inform the king about his peace intentions, but never received an answer to them. In particular, he tried to convey such an offer through the wealthy Russian landowner Ivan Yakovlev, father of Alexander Herzen, who was forced to stay in Moscow with his young son and his mother during the occupation of Moscow by Napoleon. Napoleon made his last attempt on October 4, when he sent to the Kutuzov camp (in Tarutino) the Marquis of Loriston, who was the ambassador to Russia before the war.[K 4]

Some Soviet historians (for example, Yevgeny Tarle) believed that Napoleon cherished plans for liberating the peasants from serfdom as the last resort to the Russian tsar, which the Russian nobility was most afraid of;[K 5] the occupation itself caused a certain undermining of the established social structure (there are cases when serfs declared to their landlords, especially those who were about to flee, that they no longer consider themselves bound by their obligations).[14]

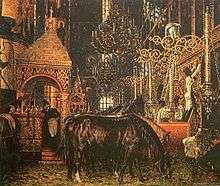

Sacrilege

During their stay in Moscow, the French did not particularly stand on ceremony with Russian shrines; stables were set up in a number of churches. As stoves were heated with window frames, bird nests were twisted under the ceiling of buildings. In some churches, melting furnaces were set up for the smelting of gold and silver utensils.[18] After the Russians returned, the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin had to be sealed so that the crowd could not see what was done inside outrage:

I was overwhelmed with horror, finding this revered temple, which spared even the flame, now put upside down the godlessness of the unbridled soldier, and made sure that the state in which it was needed to be hidden from the eyes of the people. The relics of the saints were disfigured, their tombs filled with sewage; decorations from tombs are torn off. The images adorning the church were stained and split.

Another memoirist notes that rumors about the blasphemous actions of the French in relation to Orthodox shrines were exaggerated by rumors, because "most of the cathedrals, monasteries and churches were turned into guard barracks" and "no one was allowed to enter the Kremlin under Napoleon".[20][K 6] The most revered shrines were hidden before leaving the city: "In the Miracle Monastery there were no crayfish of Saint Alexei, it was taken out and hidden by Russian piety, as well as the relics of Saint Tsarevich Demetrius, and I found only one cotton paper in the tomb".[20]

Alexander Shakhovskoy cites the only case of a deliberate insult to the feelings of Orthodox believers: "a dead horse was dragged into the altar of the Kazan Cathedral and put in place of the thrown throne".[20]

Abandonment of Moscow by Napoleon

On October 18, 1812, Napoleon realized the futility of concluding peace agreements with the Russians and the impossibility of providing food for the French troops stationed in Moscow and the surrounding area, as a result of actively opposing attempts to establish supplies to the French army both from the Russian army and from the civilian population. After that, Napoleon decided to leave Moscow. To make such a decision, the French emperor was also prompted by sharply worsened weather with early frosts.

The reasons why Napoleon abandoned his initial plans to spend the winter in Moscow are causing controversy among historians. In addition to problems with foraging and warm clothing, the emperor was disturbed by looting and drunkenness of the army, its general decomposition in the absence of real combat prospects. In this state, he could not lead the fighters to the capital of the empire – Saint Petersburg.

On October 18, part of Kutuzov's army clashed with units of the French army commanded by Murat, who were in an observing position on the Chernishna River in front of Tarutino, where Kutuzov's headquarters were located. The attack was carried out by General Bennigsen against the will of Kutuzov. This clash unfolded into a battle, later called the Battle of Tarutino, and ended with Murat being driven back to the village of Spas-Kuplya. This episode showed Napoleon that Kutuzov intensified after Borodin, and further initiatives of the Russian army could be expected.

Napoleon gave the order to Marshal Mortier, who was appointed by him the Moscow Governor General, to set fire to wine shops, barracks and all public buildings in the city, with the exception of the Orphanage, before setting fire to Moscow, to set fire to the Kremlin palace and put gunpowder under the Kremlin walls. The Kremlin explosion was to follow the departure of the last French troops from the city.

On October 19, by order of Napoleon, the army from Moscow moved along the Old Kaluga Road. Only the corps of Marshal Mortier remained in Moscow. Initially, Napoleon intended to attack the Russian army and, having defeated it, get into the war-ravaged regions of the country to provide its troops with food and fodder. Napoleon made his first stop at night in the village of Troitsky on the banks of the Desna River. Here for several days was his main apartment. While here, he abandoned his original plan – to attack Kutuzov, since in this case he had to withstand a battle like Borodinsky, with even more unclear prospects for victory than in Borodino. But even if the new battle ended in victory for Napoleon, it could no longer change the main thing: the abandonment of Moscow by him. Napoleon foresaw the impression that his departure from Moscow would make in Europe, and was afraid of this impression.

Napoleon decided to turn right from the Old Kaluga Road, bypass the location of the Russian army, go out onto the Borovskaya Road, go through the untouched places along the Kaluga Governorate to the south-west, moving to Smolensk. He intended, calmly reaching Maloyaroslavets and Kaluga to Smolensk, to winter in either Smolensk or Vilna, and to continue the war with Russia in the future.

Undermining the Kremlin

"I left Moscow, ordering to blow up the Kremlin", Napoleon wrote to his wife on October 10. The night before he had sent from his main apartment in the village of Troitsky, Marshal Mortier, the order to finally leave Moscow and immediately join the army with his corps, and to blow up the Kremlin before the performance. This order was only partially fulfilled, as in the bustle of a sudden speech, Mortier did not have enough time to properly deal with this matter. To its foundation, only the Vodovzvodnaya Tower was destroyed, the Nikolskaya Tower, 1st Bezymyannaya and Petrovskaya Towers, the Kremlin wall and part of the arsenal were badly damaged. The Faceted Chamber burned from the explosion.

As contemporaries noted with malice, when trying to undermine the tallest building in Moscow, Ivan the Great Bell Tower, it remained unharmed, unlike the later outbuildings:[20]

The huge annex to Ivan the Great, torn off by the explosion, collapsed beside it and at its feet, and it stood just as majestically as it had just erected by Boris Godunov to feed his workers in hungry times, as if mocking at the barren fury of the barbarism of the 19th century.

Return of the Russians

After the French left Moscow, the cavalry vanguard of the Russian army was the first to enter the city under the command of Alexander Benkendorf (whose commander Wintzingerode was then captured by Marshal Mortier). On October 26, Benckendorf wrote to Mikhail Vorontsov:[21]

We entered Moscow on the evening of the 11th. The city was given for plunder to peasants, who flocked a great many, and all drunk; Cossacks and their foremen completed the rout. Entering the city with hussars and life-Cossacks, I considered it a duty to immediately take command over the police units of the unfortunate capital: people killed each other on the streets, set fire to houses. Finally, everything calmed down and the fire was extinguished. I had to endure several real battles.

Other memoirists also report that the Russian army found in the city crowds of peasants engaged in drunkenness, robbery and vandalism.[14][22] Here, for example, the testimony of Alexander Shakhovskoy:[20]

The peasants near Moscow, of course, are the most idle and quick-witted, but the most depraved and greedy in all of Russia, assured of the enemy's exit from Moscow and relying on the turmoil of our entry, arrived on carts to capture the unlawed, but Count Benckendorf calculated differently and ordered to be loaded onto their carts and carrion and taken out of town to places convenient for burial or extermination, which saved Moscow from the infection, its inhabitants from peasant robbery, and peasants from sin.

Moscow Chief Police Officer Ivashkin, in a report to Rostopchin dated October 16, estimates the number of corpses removed from the streets of Moscow at 11,959, and horse – at 12,546.[18] Upon returning to the city, Rostopchin ordered not to arrange a property redistribution and leave the looted goods to those in whose hands it fell,[K 7] limiting itself to compensation for the victims. Learning about this order, the people rushed to the Sunday market near the Sukharev Tower: "On the first Sunday the mountains of the looted property blocked a huge area, and Moscow surged into the unprecedented market!" (Gilyarovsky). In the imperial manifesto of August 30, 1814, an amnesty was declared for most of the crimes committed during the Napoleonic invasion.[14]

See also

- War and Peace – the novel contains paintings of the French-occupied Moscow.

Notes

- The use of the term "French" in relation to the army of Napoleon is conditional. Italians, Württemberg, Westphalian, Hessian were no less active in the sack of Moscow. Relatively high levels of discipline were distinguished by Poles, Bavarians, Saxons.

- The official of the Russian Ministry of Finance, Fyodor Korbeletsky, who was captured by the French on August 30 and was at Napoleon's main headquarters for 3 weeks, left detailed notes on what was happening during this period. Notes by Korbeletsky "A Brief Narrative About the French Invasion of Moscow and Their Stay in It. With the Appendix of an Ode in Honor of the Victorious Russian Army" were published in Saint Petersburg in 1813.

- There are several versions of the fire – organized arson when leaving the city (usually associated with the name of Fyodor Rostopchin), arson by Russian scouts (several Russians were shot by the French on such a charge), uncontrolled actions by the invaders, a random fire that spread due to the general chaos in the abandoned city. There were several pockets of fire, so it is possible that all versions are true to one degree or another.

- Kutuzov received Loriston at headquarters, refused to negotiate peace or armistice with him, and only promised to bring Alexander's proposal to Napoleon. But, as it is known, Alexander I also ignored this proposal of Napoleon.

- The rationale is that Napoleon intended to look for information about Pugachev in the Moscow archive, asked to sketch the manifesto for the peasantry, wrote to Evgeny Bogarne, that it would be nice to cause an uprising of peasants.

- Of course, the guards did not keep order in the temples. According to Shakhovsky's recollections, "wine flowing out of broken barrels was dirty in the Archangel's Cathedral, junk was thrown out of the palaces and the Armory, among other things, two naked stuffed animals representing old armor".

- Rostopchin and Ivashkin themselves profit from the distribution of property confiscated from the stores of foreigners who chose to leave Moscow with the retreating French army.

References

- Arthur Chuquet (1911). Lettres de 1812. Paris: Éditions Honoré Champion. p. 31.

- Popov 2009, p. 634–635.

- Zemtsov 2010, p. 7–8.

- Clemens Cerrini de Monte Varchi (1821). Die Feldzüge der Sachsen, in den Jahren 1812 und 1813. Dresden: Arnold. p. 388.

- 1812 in Diaries, Notes, and Memoirs of Contemporaries: Materials of the Military Scientific Archive of the General Staff. 1. Vilna: Printing House of the Headquarters of the Vilnius Military District. Compiled by Vladimir Kharkevich. 1900. pp. 206–208.

- Zemtsov 2015, p. 233.

- Zemtsov 2016, p. 224.

- The Son of the Fatherland, a Historical and Political Journal. Part Seven. Saint Petersburg, in the Printing House of Friedrich Drechsler, 1813. Page 109

- "Napoleon in Moscow – Walks in Moscow". Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Napoleon in Russia Through the Eyes of Russians. Moscow: Zakharov, 2004. Page 161

- Zemtsov 2018, p. 78.

- Martin 2002, p. 473.

- Zemtsov 2015, p. 244; Zemtsov 2018, p. 78–79.

- Martin 2002.

- See also the section Sacrilege

- Vladimir Zemtsov. Napoleon and the Fire of Moscow

- Fire in Moscow

- Sergey Teplyakov. "Moscow in 1812"

- Alexander Benckendorf. Scrapbook

- Alexander Shakhovskoy. The First Days in Burnt Moscow. September and October 1812. According to the Notes of Prince Alexander Shakhovsky // Fire of Moscow. According to the Memoirs and Notes of Contemporaries: Part 2 – Moscow: Education, 1911. Pages 95, 99

- Alexander Benckendorf. Scrapbook

- Sergey Bakhrushin. Moscow in 1812. Edition of the Imperial Society of History and Antiquities of Russia at Moscow University, 1913. Page 26

Sources

- 1812 in the Memoirs of Contemporaries (Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences ed.). Moscow: Science. Executive Editor Andrei Tartakovsky. 1995. p. 202. ISBN 5-02-009607-5.

- Nikolay Muravyov. Notes // Russian Archive, 1885, No. 9, Page 23

- "The French in Moscow". Russian Memoirs. Favorite Pages. 1800–1825 // Moscow. Publisher: Pravda, 1989. Pages 164–168

- Fedor Korbeletsky. A Short Story About the French Invasion of Moscow and Their Stay in It. With the Application of an Ode in Honor of the Victorious Russian Army – Saint Petersburg. 1813

- Zemtsov, Vladimir (2010). 1812 Year. Moscow Fire. 200th Anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812. Moscow: Book. p. 138. ISBN 978-5-91899-013-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zemtsov, Vladimir (2016). Moscow Under Napoleon: the Social Experience of Cross-Cultural Dialogue (PDF). 4 (Quaestio Rossica ed.). Yekaterinburg: Ural Federal University Named After Boris Yeltsin. pp. 217–234. ISSN 2311-911X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zemtsov, Vladimir (2014). Napoleon in Moscow. 200th Anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812. Moscow: Media Book. p. 323. ISBN 978-5-91899-071-1.

- Zemtsov, Vladimir (2018). Napoleon in Russia: The Sociocultural History of War and Occupation. The Era of 1812. Moscow: ROSSPEN. p. 431. ISBN 978-5-8243-2221-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zemtsov, Vladimir. Napoleon and the Fire of Moscow // Patriotic War of 1812. Sources. Monuments. Problems. Pages 152–162

- Zemtsov, Vladimir (2015). "The Fate of the Russian Wounded Left in Moscow in 1812" (PDF). Borodino and the Liberation Campaigns of the Russian Army of 1813–1814: Materials of the International Scientific Conference (Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation ed.). Borodino: Borodino Military History Museum-Reserve. Compiled by Alexander Gorbunov. pp. 225–250. ISBN 978-5-904363-13-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zemtsov, Vladimir (2015). "The Fate of the Russian Wounded Abandoned in Moscow in 1812". 28 (3) (The Journal of Slavic Military Studies ed.). Routledge: 502–523. ISSN 1351-8046. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

- Zemtsov, Vladimir (2015). "The Fate of the Russian Wounded Abandoned in Moscow in 1812". 28 (3) (The Journal of Slavic Military Studies ed.). Routledge: 502–523. ISSN 1351-8046. Cite journal requires

- Nikolay Kiselev. The Case of Officials of the Moscow Government, Established by the French, in 1812 // Russian Archive, 1868 – 2nd Edition – Moscow, 1869 – Columns 881–903

- Moscow Monasteries During the French Invasion. A Modern Note for Presentation to the Minister of Spiritual Affairs, Prince Alexander Golitsyn // Russian Archive, 1869 – Issue 9 – Columns 1387–1399

- Maria Pavlova, Olga Rozina (2018). "Moscow City Administration During the French Occupation (September–October 1812)". Actual Issues of Local Self-Government in the Russian Federation: a Collection of Scientific Articles Based on the Results of the 1st All-Russian Scientific-Practical Conference Dedicated to the Day of Local Self-Government (April 26–27, 2018). Sterlitamak: Publishing House of the Sterlitamak Branch of Bashkir State University. pp. 92–97.

- Popov, Andrey (2009). "The French in Moscow in 1812". Patriotic War of 1812. Russian Historical Library. 2: Napoleon's Invasion of Russia. Moscow: Past. Compilation, Introduction, Notes by Sergey Nikitin. pp. 625–807. ISBN 978-5-902073-70-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Osip Reman (1812). The Voice of a Moscow Resident. Moscow. p. 16.

- Yevgeny Tarle. Chapter 13. Napoleon's Invasion of Russia in 1812 // Napoleon

- Andrey Tartakovsky (1973). "The Population of Moscow During the French Occupation". Historical Notes. 92 (Institute of History, Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union ed.). Moscow: Science. pp. 356–379.

- Peter Shalikov (1813). Historical News of the Stay of the French of 1812 in Moscow. Moscow. p. 64.

- Martin, Alexander (2002). "The Response of the Population of Moscow to the Napoleonic Occupation of 1812". The Military and Society in Russia, 1450–1917. pp. 469–489.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)