Flamboyant

Flamboyant (from French: flamboyant, lit. 'flaming') is an ornate architectural style developed in Europe in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, from around 1375 to the middle 16th century.[1] Part of the tradition of Gothic architecture, it is characterized by double-curves forming flame-like shapes in the bar-tracery, which give the style its name.[1][2] A form of Late Gothic architecture, Flamboyant tracery is recognizable for its flowing forms, influenced by the earlier Curvilinear tracery of the Second Gothic (or Second Pointed) styles.[1] Very tall and narrow pointed arches and gables, particularly double-curved ogee arch are common in buildings of the Flamboyant style.[2] In most regions of Europe, Late Gothic styles like the Flamboyant displaced or transformed earlier traditions.[3]

Particularly popular in Continental Europe, through theoretical texts, architectural drawings, travel, and expertise architects and masons of the 15th and 16th centuries exchanged architectural knowledge across cultures. (e.g. between the Kingdom of France, the Principality of Catalonia, the Duchy of Milan, and Central Europe among others).[4][5] These factors helped transmit Flamboyant ornament and design across Europe.[6][7] Notable examples of Flamboyant style are the west porch of the parish Church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen, (c.1500–14), the west front of Troyes Cathedral, and the Great West Window of York Minster.[1] Further major examples include the Chapel of the Constable of Castile (Spanish: Capilla del Condestable) at Burgos Cathedral (1482–94); Notre-Dame de l'Épine in Champagne; the north spire of Chartres Cathedral (1500s–); and Segovia Cathedral (1525–).[8]

Central Europe began to lead the emergence of the new, international style with the construction of the new Prague Cathedral (1344–) under the direction of Peter Parler.[9] This model of rich and variegated tracery and intricate reticulated rib-vaulting was definitive in the Late Gothic of continental Europe, emulated not only by the collegiate churches and cathedrals, but by urban parish churches which rivalled them in size and magnificence.[9] Use of ogees was especially common.[10]

Flamboyant forms spread from France to the Iberian Peninsula, where the Isabelline style became the dominant mode of prestige construction in the Crown of Castile during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, contemporary with the Manueline style occurred during the same period in the Kingdom of Portugal. In Central Europe, the Sondergotik ("Special Gothic") style was contemporary with the Flamboyant in France and the Isabelline in Spain.

_Notre-Dame_020.jpg)

The term was first used by the French artist Eustache-Hyacinthe Langlois (1777–1837) in 1843,[11] and then the English historian Edward Augustus Freeman in 1851.[12] In architectural history, the Flamboyant is considered the last phase of French Gothic architecture, and appeared the last decades of the 14th century, succeeding the Rayonnant style, and prevailing until its gradual replacement by Renaissance architecture during the first third of the 16th century.[13]

Notable examples of Flamboyant ecclesiastical monuments in France include the Saint-Chapelle de Vincennes; the west front of the Trinity Abbey, Vendôme. Significant examples of civil architecture include the Palace of Jacques Cœur in Bourges and the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris.

In addition to the Flamboyant style, similar and related developments occurred in England during the same general period, which are typically referred to as the Decorated style and Perpendicular Gothic.[13]

Origins

Although the precise origins of the Flamboyant style remain unclear,[14] it likely emerged in northern France and the County of Flanders during the late fourteenth century.[15] Parts of these lands were involved in the cloth trade with the Kingdom of England or were under the control of John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, regent of France for his nephew Henry VI, King of France from 1422 to 1453.[15] Through this direct connection, the flickering, flame-like tracery motifs after which the style is named may have been “inspired by the English Decorated style.”[15] In addition, the Duchy of Normandy was in personal union with England until the 13th century, while during the Hundred Years War Rouen, capital of Normandy, was again English territory from 1419 until 1449.[16] Earlier in the conflict John, Duke of Berry was taken hostage in England.[17] The ongoing war provided many opportunities for exchange as evidenced by the fireplace in the ducal palace in Poitiers and the paneled, screen-like upper parts of the west façade of Rouen Cathedral.[18]

Tracery patterns of the fourteenth century seem to fall into either the category of rich, flame-like forms inspired by the English Decorated (e.g. west façade of York Minster) or the “paneled severity” of English Perpendicular style (e.g. King's College Chapel, Cambridge).[19] According to Robert Bork, “continental builders borrowed almost exclusively from the Decorated style, which had largely passed out of fashion in England by 1360, rather than from the more current Perpendicular style.”[17] The clear rejection of the grid-like forms in France indicates some awareness of the contrasting styles.[17] Still, the emergence of the Flamboyant style was a gradual process. What has been termed “proto-Flamboyant” appeared at the royal abbey-church of Saint-Ouen in Rouen in the inner wall of the north transept between 1390-1410.[5] No flowing, double-curved forms were used there, but the “eight double lancet panels seem to spin around a quatrefoil center.”[5] Although this rose motif appears dynamic and in motion, its design was not based on the double-curve. Nevertheless, it is an early example of experimentation with tracery forms that anticipates the use of flowing, double-curve forms in Normandy. More so than the great churches of northern France, palaces constructed by royal and elite patrons provided more "fertile grounds for innovation"[18] with curvilinear tracery in France while England turned to the Perpendicular style.

France

The term "Flamboyant" was not used to describe architecture during the Middle Ages, but was coined later in the early nineteenth century "primarily to refer to French monuments"[20] with flame-like curvilinear tracery constructed between circa 1380 and 1515. The Flamboyant style appeared in France at a particularly difficult time, during the Hundred Years War against England (1337-1444), but nonetheless construction of new cathedrals, churches, and civil structures—as well as additions to existing monuments—went ahead in France, and continued throughout the early 16th century. In addition to richly articulated façades, very high, lavishly decorated porches, towers, and spires were particular features of the Flamboyant style. Although wealthy patrons were initially reluctant to shift away from the elegance and visual logic of the older Rayonnant style and its association with king Louis IX, formative examples of the Flamboyant style in France appeared first in royal palaces.[21] These initial experiments consisted of deploying curvilinear tracery for John, Duke of Berry, in his castle chapel (1382) at Riom and the fireplace in the great chamber (1390s) of the ducal palace at Poitiers, and in the La Grange chapels (c. 1375)[22] at Amiens Cathedral.[21]

Royal and elite palaces were also some of the earliest monuments constructed completely in the Flamboyant style. Located in Bourges, the Palace of Jacques Cœur, the treasurer of the King, constitutes a key example. Constructed between 1444 and 1451, it features a combination of residential and official wings richly decorated with gables, turrets, and chimneys arranged around a central courtyard.[23] The Château de Châteadun, which was transformed between 1459 and 1468 by Jehan de Dunois, the half-brother of king Charles VI, is another striking example and among the earliest residences built essentially for leisure in France.[24] In addition to featuring one of the seven remaining Sainte-Chapelle chapels, the château also includes an elegant spiral staircase. The corresponding façade is decorated with characteristic flame-like tracery in the windows and also includes dormers with fleur-de-lys, indicating that the owner of the building is a descendant of Charles V. Another notable example is the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris, originally the residence of the abbot of Cluny, now the Museum of the Middle Ages. Fine flamboyant details are found in the chapel, the doorways, windows, tower, and roofline.[23] A late example of Flamboyant civil architecture in France is the Parlement de Normandie, now the Palais de Justice, of Rouen (1499-1528), with slender, crocketed pinnacles and lucarnes terminated with fleurons designed by architects Roger Ango and Roulland Le Roux.[25]

.jpg) Flamboyant openwork tracery, fireplace and chimney, Salle des pas perdus, Palace of Poitiers (c. 1390)

Flamboyant openwork tracery, fireplace and chimney, Salle des pas perdus, Palace of Poitiers (c. 1390) Chapels commissioned by Jean de la Grange, northwest corner, Amiens Cathedral (c. 1375). Note the use of curvilinear mouchettes and soufflets at the top of the windows.

Chapels commissioned by Jean de la Grange, northwest corner, Amiens Cathedral (c. 1375). Note the use of curvilinear mouchettes and soufflets at the top of the windows.- Palace of Jacques Coeur, Bourges (1444-1451)

.jpg) The Dunois staircase, Château de Châteaudun (1459-1468)

The Dunois staircase, Château de Châteaudun (1459-1468)- Gable window of the Hotel de Cluny, Paris (15th century)

Lucarne, west façade of the former Parliament of Normandy, now the Palais de Justice, Rouen (1499-1507)

Lucarne, west façade of the former Parliament of Normandy, now the Palais de Justice, Rouen (1499-1507)

.jpg)

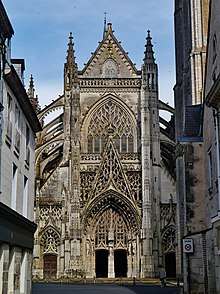

In the fifteenth century, there were relatively few churches constructed entirely in the Flamboyant style in France, where it was more common to commission new, major additions or repairs to older, extant monuments. One significant exception to this trend was the parish Church of Saint-Maclou in Rouen. Commissioned by the Dufour family during the English occupation of Rouen, the remarkably homogenous design of the new parish church reflects the vision of Pierre Robin, the sole master mason hired in 1434 to draft the drawings that governed all construction until the church was consecrated in 1521.[26] Referred to as "monumental architecture in the miniature," the church has elegant double-tiered flying buttresses, fully developed transept façades with portals, curvilinear rose windows, and a projecting polygonal west porch featuring flickering openwork ogee gables—all of which showcase the principles of the Flamboyant style.[27] The influence of Pierre Robin's innovative design was "far reaching in Rouen and Normandy" and lasted into the sixteenth century,[5] when Roulland Le Roux oversaw work on the upper parts of the Tour de Beurre ("Butter Tower") (1485-1507) and the central portal (1507-1510) of Rouen Cathedral.[2] Increasing specialization in Gothic workshops and lodges led to the sophisticated forms characteristic of structures completed in the early sixteenth century, such as the south façade and porch of the church of Notre-Dame de Louviers (1506-1510) and the north tower of Chartres Cathedral designed by architect Jean de Beauce (1507-1513).[28]

The style was also prevalent in other regions, such as the Île-de-France, where the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes, a royal chapel constructed by King Charles V of France, serves as a notable example. It was located just outside Paris, next to the massive Château de Vincennes. It took its inspiration from the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, but in this case the structure had one single floor, and the windows consisting of curvilinear tracery covered nearly all of the walls. It was begun in 1379, but construction was halted by the Hundred Years War; it was not completed until 1552.[29] One significant Flamboyant landmark in Paris is the Tour Saint-Jacques, all that remains of the Church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie ("Saint James of the butchers"), built 1509-23, located close to Les Halles, the Paris central market.[upper-alpha 1]

The Butter Tower of Rouen Cathedral (1485-1507)

The Butter Tower of Rouen Cathedral (1485-1507) South porch of Notre-Dame de Louviers (1506-1510)

South porch of Notre-Dame de Louviers (1506-1510).jpg) Detail of the North Tower of Chartres Cathedral (1507-1513)

Detail of the North Tower of Chartres Cathedral (1507-1513)- Facade of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes (begun 1379, finished 1480)

Tour Saint-Jacques, (1509-1523) Paris

Tour Saint-Jacques, (1509-1523) Paris

Beyond northern France, churches were also enlarged and updated with additions in the Flamboyant style. Due to its size and decoration, the abbey-church of Saint-Antoine in Saint-Antoine-l’Abbaye (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes) is one of the most significant examples of Gothic architecture in southeast France. The abbey-church was a key pilgrimage site in the Middle Ages because it contained the relics of Saint Anthony the Great. The relics housed in the five-aisled church were especially sought out by those who were suffering from “Saint Anthony’s Fire” (ergot poisoning). Royal figures also visited the abbey-church, including Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor (1415), Louis XI of France (1475), and Anne of Brittany (1494).[30] The most prominent architectural feature of the church is its monumental west façade completed in the Flamboyant style in the fifteenth century. The façade has a central portal flanked by secondary portals and a large lancet window with curvilinear tracery, including triskeles. Additional ornamentation in the form of naturalistic vegetation, gables, pinnacles, and delicate sculpture niches are further testaments of the talents of the masons’ workshop.[31] However, work on the façade stopped before it was completed, as there is no evidence of the iron hooks needed to attach figural sculptures.[31]

At Lyon Cathedral, the Bourbons chapel, built during the last decades of the fifteenth century by the Cardinal Charles II, Duke of Bourbon and his brother Pierre de Bourbon, son-in-law of Louis XI, is a key example of the trend of expanding existing Gothic churches in the newer Flamboyant style.[32] Consisting of two bays, it features a small oratory and a sacristy. The pendant vaults are decorated with finely carved keystones. The mouldings of the transverse ribs are decorated with the monograms of Charles de Bourbon, Pierre de Bourbon, and his wife, Anne of France.

- West façade, Abbey-church of Saint-Antoine, Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye (15th century)

.jpg) Bourbons chapel, Lyon Cathedral, engraving by Ebenezer Challis after a drawing by Thomas Allom (19th century)

Bourbons chapel, Lyon Cathedral, engraving by Ebenezer Challis after a drawing by Thomas Allom (19th century) Pendant vaults and mouldings with monograms, Bourbons chapel, Lyon Cathedral (late 15th century)

Pendant vaults and mouldings with monograms, Bourbons chapel, Lyon Cathedral (late 15th century)

Transition between Flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance (1495-1530)[upper-alpha 2]

The transition from Flamboyant Gothic to early French Renaissance began during the reign of Louis XII (1495) and lasted until roughly 1525-1530. This is a brief transition period in which the ogee arch and naturalism of the Gothic style was blended with round arches, flexible forms, and stylized antique motifs typical of Renaissance architecture. Notably, a good deal of Gothic decoration is apparent at the Château de Blois, but it is totally absent from the tomb of Louis XII housed in the abbey-church of Saint-Denis.

In 1495 a colony of Italian artists was established in Amboise and worked in collaboration with French master masons. This date is generally considered to be the starting point of the period of interaction between the Flamboyant Gothic and early French Renaissance styles. In general, theories of building design and structure remained French while surface decoration became Italian. However, there were connections between French architectural production and other stylistic traditions, including Plateresque in Spain and the decorative arts (e.g. painting and stained glass) of the north—especially Antwerp.[33]

The limits of this style, called style Louis XII in French, were variable—especially outside the Loire Valley. In addition to the seventeen-year reign of Louis XII (1498-1515), this period included the end of the reign of Charles VIII and the beginning of that of Francis I, whose rule corresponded with a definitive stylistic turn. Indeed, the creation of the School of Fontainebleau in 1530 by Francis I is generally considered the turning point of the acceptance and establishment of the Renaissance style in France.[34] Early evidence of the intermingling of Flamboyant and classicizing decorative motifs can be found at the Château de Meillant, which was transformed by Charles II d’Amboise, governor of Milan, in 1473. The structure remained fully medieval, but the superposition of the windows in bays connected to each other by extended cord-like pinnacles foreshadows the grid designs of the façades of early French Renaissance monuments. Other notable features include the entablature with classical egg-and-dart motifs surmounted by a Gothic balustrade and the treatment of the upper part of the helical staircase with a semicircular arcade equipped with shells.[35]

In the final years of the reign of Charles VIII, experimentation with Italian ornamentation continued to enrich and mix with the Flamboyant repertoire.[36] With the ascendancy of Louis XII, French masons and sculptors were further exposed to new, classicizing motifs popular in Italy.[36]

In architectural sculpture, the systematic contribution of Italian elements and even the "Gothic" reinterpretation of Italian Renaissance works is evident in the Abbey of Saint-Pierre in Solesmes, where the Gothic structure takes the form of a Roman triumphal arch flanked by pilasters with Lombard candelabra. Gothic foliage, now more jagged and wilted as seen at the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris, mingles with portraits of Roman emperors in medallions at the Château de Gaillon.[37] The maison des Têtes (1528-1532) in Valence is still another striking example where Flamboyant blind tracery and foliage mix with classicizing figures, medallions, and portraits of Roman emperors.

In architecture, the use of brick and stone on buildings from the sixteenth century can be observed (e.g. Louis XII wing of the Château of Blois). The French high roofs with turrets in the corners and the façades with helical staircases perpetuated the Gothic tradition, but the systematic superposition of the bays, the removal of the lucarnes, and the appearance of loggias influenced by the villa Poggio Reale and the Castel Nuovo of Naples are evidence of a new decorative art in which the structure remains deeply Gothic. The spread of ornamental vocabularies from Pavia and Milan also played major roles. Equally important is the fact that Italians also designed formal gardens and fountains to complement French monuments as seen at the Château de Blois in 1499 and the Château de Gaillon shortly thereafter.

The incorporation of Flamboyant Gothic with the classicizing forms of Italy produced eclectic, hybrid structures that were rooted in traditional French building practices yet modernized through the application of imported antique motifs and surface decoration. These transitional monuments led to the birth of French Renaissance architecture.

Louis XII wing of the Château de Blois (1498-1503)

Louis XII wing of the Château de Blois (1498-1503) Fusion of Flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance exterior decoration at Château de Gaillon (1502-1510)

Fusion of Flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance exterior decoration at Château de Gaillon (1502-1510).jpg) Burial of Christ, Solesmes Abbey (1496)

Burial of Christ, Solesmes Abbey (1496)- Chapel vault with classicizing decoration, church of Saint-Pierre, Caen, by Hector Sohier (1518-1545)

Southeast side of the church of Saint-Pierre, Caen, showing combinations of Flamboyant Gothic and antique forms

Southeast side of the church of Saint-Pierre, Caen, showing combinations of Flamboyant Gothic and antique forms The Longueville staircase, Château de Châteaudun, showing juxtaposition of Flamboyant Gothic and antique decoration

The Longueville staircase, Château de Châteaudun, showing juxtaposition of Flamboyant Gothic and antique decoration Detail of the Longueville staircase, Château de Châteaudun, showing juxtaposition of Flamboyant Gothic and antique decoration

Detail of the Longueville staircase, Château de Châteaudun, showing juxtaposition of Flamboyant Gothic and antique decoration Maison des Têtes (1528-1532), Valence

Maison des Têtes (1528-1532), Valence

Belgium

Flamboyant had little influence in England, where the Perpendicular style prevailed, but variations of Flamboyant, influenced by France but with their own characteristics, began to appear in other parts of continental Europe.[38]

Flamboyant had a particularly strong influence in Belgium, which was then part of the Spanish Netherlands, but was also a part of the Catholic diocese of Cologne. Extraordinarily high towers were a particular feature of the Belgian style. In the 15th century Belgian architects produced remarkable examples of both religious and secular Flamboyant architecture. Major examples include the tower of St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen (1452-1520), built both as a bell tower and a watch-tower for the defence of the city. The tower is 167 meters high, and was designed to have an even taller spire, 77 meters high, but only seven meters of the spire were actually built. Other notable Flamboyant cathedrals include Antwerp Cathedral, with a tower 123 metres (404 ft) high, and an unusual dome on pendentives decorated with a Flamboyant rib vault. It was never finished but was consecrated in 1521. Other notable Flamboyant cathedrals in Belgium include the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, Brussels, and Liege Cathedral.[38]

Tower of St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen (1452-1520)

Tower of St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen (1452-1520) Lantern tower, Antwerp Cathedral, consecrated 1521

Lantern tower, Antwerp Cathedral, consecrated 1521.jpg) Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, Brussels (1485-1519)

Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, Brussels (1485-1519)

While the cathedrals were remarkable, the town halls, many built by the prosperous textile merchants of Flanders, were even more flamboyant. They were among the last great statements of Gothic style as the Renaissance gradually came to Northern Europe, designed to showcase the wealth and splendour of their cities. Major examples include the town hall of Leuven (1448), with its multiple, almost fantastic towers;[38], and the town halls of Oudenaarde, Ghent (1518) and Mons (1458).[38]

- Leuven Town Hall (1448)

- Detail of the facade of Leuven Town Hall

Oudenaarde Town Hall (1526-36)

Oudenaarde Town Hall (1526-36)

Central Europe

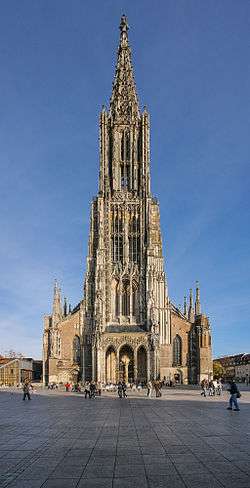

Architects in central Europe adopted some forms and elements of Flamboyant in the late 14th century and added many innovations of their own. The Late Gothic buildings of Austria, Bavaria, Saxony and Bohemia are sometimes called Sondergotik. The high triple west porch of Ulm Minster was placed at the base of the tower and was designed by Ulrich von Ensingen. The porch which was in the center of the facade, a break from earlier Gothic styles. Work on the tower was continued by Ensingen's son after 1419, and much more decoration was added in 1478-92 by another architect, Matthaus Boblinger. The spire was not added until 1881-90, which made it the tallest tower in Europe.[39]

Other remarkable towers appeared, constructed like openwork webs of stone. These included the additions to the tower of Freiburg Minster begun in 1419 by Johannes Hultz, which featured an open spiral staircase and a lacework octagonal spire.

West porch and tower of Ulm Minster (begun late 14th century, completed 19th)

West porch and tower of Ulm Minster (begun late 14th century, completed 19th) Detail of the tower of Ulm Minster, 19th century.

Detail of the tower of Ulm Minster, 19th century. Detail of the tower of Freiburg Minster

Detail of the tower of Freiburg Minster Looking up into the spire of Freiburg Minster (after 1419)

Looking up into the spire of Freiburg Minster (after 1419)

British Isles

Flamboyant architecture was not common in the British Isles, but examples are nonetheless numerous. The flame-like window tracery appeared at Gloucester Cathedral before it appeared in France.[40] In the Kingdom of Scotland, Flamboyant detailing was employed at Melrose Abbey in window tracery of the northern side of the nave and for the west window which completed the construction of Brechin Cathedral.[41] Melrose Abbey had been destroyed during the English invasion of Scotland (1385), and the initial rebuilding followed the traditions of masons from England; from c.1400, the Parisian master-builder John Morow began work on the Abbey, leaving an inscription identifying him in the church's south transept.[41] Morow had possibly been brought to Great Britain by Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas, for whom he also worked on Lincluden Collegiate Church.[42] The design of some windows in both Brechin and Melrose are so similar it is possible that Morow or his team of Continental masons worked on both. Comparison can also be made with the chapel (1379–) of the Château de Vincennes, a castle and royal residence near Paris.[41] Somewhat later, further Flamboyant work was done on the western bays of Brechin Cathedral.[41] In the Kingdom of England the contemporary Late Gothic (or Third Pointed) style, Perpendicular Gothic was prevalent from the middle 14th century, but examples Flamboyant building included the Great West Window in York Minster – the cathedral of the Archbishop of York – and the Flamboyant curvilinear bar-tracery of St Matthew's Church at Salford Priors, Warwickshire.[1][43]

Perpendicular Gothic

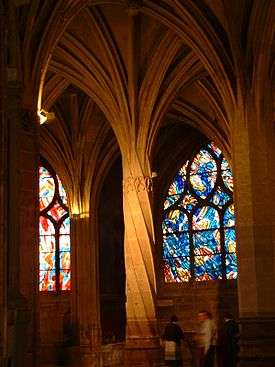

The Flamboyant Gothic of Continental Europe was distinct from, and contemporary with, Perpendicular Gothic. Both styles are categorized as Late Gothic. Unique to England, a style which emphasized great height had appeared as early as the mid-14th century, at Gloucester Cathedral.[44] The interiors of these cathedrals seemed to be great cages of glass, with an elimination of horizontal levels such as triforia. The vaults in the Perpendicular style were particularly complex, divided by extra decorative ribs into multiple compartments and further decorated with hanging gilded and painted ornaments called bosses.[44] The fan vault, with a multitude of spreading ribs, also appeared in England during this period. An early example was found in the cloister of Gloucester Cathedral (1331-1357). Gloucester also featured tracery in free-standing screens of mullions in front of the windows. Other major examples of this early Perpendicular include the nave of Canterbury Cathedral (1379-1405) and Winchester Cathedral (1394-1450).[44]

King Henry VI of England rebelled against what he considered the excesses of Decorated Gothic. In 1447 he wrote that wanted his own chapel "to proceed in large form, clean and substantial, setting apart superfluity of too great curious works of entail and busy moulding." In response to this, the King's architect, John Wastell, designed the King's College Chapel, Cambridge, with towering fan faults (1508-15). The walls seem to be composed entirely of glass, slender columns and tracery. The weight of the elaborate vaults is carried by enormous buttresses on the outside, hidden by side chapels placed between them.[45] Another monument of the late English Gothic is the Henry VII Chapel of Henry VII of England, at the east end of Westminster Abbey, which showed evidence of the influence of the French Flamboyant style.[45] The suspended pendants of the chapel are combined with cone-shaped fan vaults, supported by traverse arches with decorated edges, and decorated with octagonal turrets and trefoil oriel windows. The King's own tomb, in the centre of the chapel, was carved in 1512-18 by the Italian Pietro Torrigiano, and is among the first works of Renaissance art in England.[45]

High Altar of Gloucester Cathedral (1331-1357)

High Altar of Gloucester Cathedral (1331-1357) Windows of King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446-1451) occupy almost all the walls

Windows of King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446-1451) occupy almost all the walls Fan Vaults of King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446-1536)

Fan Vaults of King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446-1536) Pendant vaults of the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey (1503-09)

Pendant vaults of the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey (1503-09)

Spain

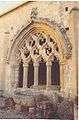

Before the unification of Spain, monuments were constructed in the Flamboyant style in the Crown of Aragon and Kingdom of Valencia. Marc Safont was among the most important architects of the of the Late Middle Ages in the region. He was commissioned to repair the Palau de la Generalitat de Catalunya in Barcelona and worked on this project from 1410 to 1425.[46] He designed the courtyard and elegant galleries of the building.[47] Also notable is the Chapel of Sant Jordi (1432-34), which features a striking façade consisting of an entry portal flanked by windows resplendent with both blind and openwork Flamboyant tracery.[46] The interior of the chapel includes a lierne vault with a keystone depicting Saint George and the dragon.

Following an earthquake in 1428, a replacement Flamboyant rose window on the west façade of the Basílica de Santa Maria del Mar in Barcelona was completed by 1459. Additional examples of the Flamboyant style include the cloister of the Convent of Sant Doménec in the Kingdom of Valencia.

Spain was united by the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469, and saw the conquest of Granada, the last stronghold of Moorish occupation, in 1492. Charles V became the Holy Roman Emperor expulsion of the Moors in 1492. Charles V of Spain became Holy Roman Emperor This was followed by a great wave of construction of new cathedrals and churches in what became known as the Isabelline style, after the queen. This late Spanish Gothic style included a mixture of French-inspired Flamboyant tracery and vaulting features, Flemish features, such as fringed arches, and other elements possibly borrowed from Islamic architecture, such as the crossed rib vaults and pierced openwork tracery of Burgos Cathedral.[48] To this Spanish architects, such as Juan Guas, added distinctive and original new features, as seen Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo (1488-1496), and the Colegio de San Gregorio (completed 1487.[49]

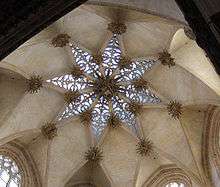

Juan de Colonia and his son Simón de Colonia, originally from Cologne, are other notable figure of the Isabelline style. They were in turn the chief architects the flamboyant features of Burgos Cathedral (1440-1481), including the open work towers and the remarkable tracery in the star vault in the Chapel of the Constable.[49]

Façade of the Saint George chapel in the Generalitat Palace, Barcelona (1432-1434)

Façade of the Saint George chapel in the Generalitat Palace, Barcelona (1432-1434)- Vault of the Saint George chapel in the Generalitat Palace, Barcelona

Rose window, west façade, Basílica de Santa Maria del Mar, Barcelona (1459)

Rose window, west façade, Basílica de Santa Maria del Mar, Barcelona (1459) Cloister of the Convent of Sant Doménec, Valencia

Cloister of the Convent of Sant Doménec, Valencia Colegio de San Gregorio (Completed 1487)

Colegio de San Gregorio (Completed 1487).jpg) Decoration of Colegio de San Gregorio (1488-1496)

Decoration of Colegio de San Gregorio (1488-1496)- Vaults of the lower cloister of the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo (1477-1504)

Facade and openwork spires of Burgos Cathedral (1440-1481) by Juan de Colonia and Simon de Colonia

Facade and openwork spires of Burgos Cathedral (1440-1481) by Juan de Colonia and Simon de Colonia Star vault in the Constable Chapel of Burgos Cathedral by Simón de Colonia

Star vault in the Constable Chapel of Burgos Cathedral by Simón de Colonia

Portugal

The Manueline style was named for King Manuel I of Portugal (reigned from 1495-1523). The style was created in particular to show that Portugal was architecturally as well as politically independent of Spain. Batalha Monastery, begun in 1387 to celebrate the victory of Portugal over King Juan of Castile which brought independence, was modified after 1400 in a Flamboyant style. In the same building included elements borrowed by the English Perpendicular style, tracery inspired by French Flamboyant, and German-inspired openwork steeples.[50]

In 1495 Portuguese navigators opened a sea-route to India, and also began trading with Brazil, Goa, and Malacca, bringing enormous wealth into Portugal. King Manuel funded a series of new monasteries and churches covered with decoration inspired by banana trees, sea shells, billowing sails, seaweed, barnacles and other exotic elements, as a monument to the Portuguese navigator Vasco de Gama, and to celebrate Portugal's overseas empire. The most lavish example of this decoration is found on the Convent of Christ in Tomar (1510-1514).[51]

Batalha Monastery (1386-1517)

Batalha Monastery (1386-1517)- Flamboyant window of Batalha Monastery (1386-1517)

- Jeronimos Monastery, Belem (1501-158)

.jpg) Marine themed decoration of the Chapter House window of the Convent of Christ (Tomar) (1510-1514)

Marine themed decoration of the Chapter House window of the Convent of Christ (Tomar) (1510-1514)

Characteristics

Tracery

The flamboyant tracery designs were the most characteristic feature of the style.[52] They appeared not only in the stone mullions or framework of the windows, but also in complex pointed blind arcades and arched gables that were stacked one over the other, and which often covered the entire façade. They were also used in balustrades and other features.[53] Interlocking openwork gables and balustrades, as seen on the west porch of the church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen, were often used to disguise or diffuse the mass of buildings.

Flamboyant windows were often composed of two arched windows, over which was a pointed oval design divided by curving lines, called soufflets and mouchettes. Good examples are found in the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen.[54] Mouchettes and soufflets were also applied in openwork form to gables, as seen on the west façade of Trinity Abbey, Vendôme, and in Flamboyant rose windows like at Sens Cathedral and Beauvais Cathedral.

- Flamboyant window tracery, Limoges Cathedral

Openwork gable and balustrade, west porch, church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen

Openwork gable and balustrade, west porch, church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen Mouchettes in the south façade windows of the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen

Mouchettes in the south façade windows of the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen A soufflet from a window on the south façade of the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen

A soufflet from a window on the south façade of the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen West façade of Trinity Abbey, Vendôme

West façade of Trinity Abbey, Vendôme Flamboyant rose window, north transept, Sens Cathedral

Flamboyant rose window, north transept, Sens Cathedral North rose window, Beauvais Cathedral

North rose window, Beauvais Cathedral

Façades and Porches

In its monumental manifestation, the term "Flamboyant" typically refers to church façades, though it equally applies to some secular buildings such as the Palais de Justice in Rouen.[20] Church façades and porches were often the most elaborate architectural features of towns and cities, especially in France, and frequently projected out onto marketplaces and town squares.[55] The intricate and dazzling forms of many façades and porches often appealed to their urban contexts; in some cases, new façades or porches were designed to create impressive architectural vistas when viewed from a specific street or square.[56] This architectural response to increasing concerns with the aesthetics of urban space is particularly notable in Normandy, where a striking group of late 15th- and early 16th-century projecting polygonal porches were all constructed in the Flamboyant style (e.g. Notre-Dame, Alençon; La Trinité, Falaise; Notre-Dame, Louviers; and Saint-Maclou, Rouen).[21] Martin Chambiges, the most prolific French architect between c. 1480 and c. 1530, combined three-dimensional forms, such as nodding ogees, with a miniaturized vocabulary of niches, baldachins, and pinnacles to produce dynamic façades with a new sense of depth at Sens Cathedral, Beauvais Cathedral, and Troyes Cathedral.[21] The addition of sumptuous Flamboyant façades or porches provided new public faces to older monuments that survived the Hundred Years' War.[57] Façades and porches often used the arc en accolade, an arched doorway which was topped by short pinnacle with a fleuron, or carved stone flower, often like a lily. The short pinnacle bearing the fleuron had its own decoration of small sculpted forms like twisting leaves of cabbage or other naturalistic vegetation. In addition, there were two slender pinnacles, one on either side of the arch.[58]

- West porch, Notre-Dame d'Alençon

West porch, La Trinité, Falaise

West porch, La Trinité, Falaise.jpg) West porch, church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen

West porch, church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen South transept façade, Beauvais Cathedral

South transept façade, Beauvais Cathedral North transept façade, Sens Cathedral

North transept façade, Sens Cathedral West façade, Troyes Cathedral

West façade, Troyes Cathedral Parlement de Normandie, Rouen, now the Palais de justice

Parlement de Normandie, Rouen, now the Palais de justice

Vaults, Piers, and Mouldings

Elision, or the elimination of capitals coupled with the introduction of continuous and "dying" mouldings, are additional noteworthy characteristics of which the parish church of Saint-Maclou in Rouen is a key example.[21] The uninterrupted fluidity and merging of disparate forms led to the emergence for the first time of decorative Gothic vaults in France.[21]

Another characteristic feature were vaults with additional types of ribs, called the lierne and the tierceron, whose functions were purely decorative. These ribs spread out over the surface to make a star vault; a ceiling of star vaults gave the ceiling a dense network of decoration.[59] Another feature of the period was a type of very tall round piller without a capital, from which ribs sprang and spread out upwards to the vaults. They were often used as the support for a fan vault, which branched upward like a spreading tree. A fine example is found in the chapel of the Hotel de Cluny in Paris (1485-1510).[53][58]

Vaults of the chapel of the Hotel de Cluny (1485-1510)

Vaults of the chapel of the Hotel de Cluny (1485-1510)- Nave of the church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen. Note the absence of capitals and use of continuous mouldings throughout.

Twisted pillar of Church of Saint-Séverin, Paris (1489-1520)

Twisted pillar of Church of Saint-Séverin, Paris (1489-1520)- Transept pier and vaults, Basilica of Saint-Nicolas-de-Port

- Chapelle du Saint-Esprit, Rue

Notable Examples of Religious buildings in France

- Auch (Gers), Auch Cathedral (except the façade)

- Beauvais (Oise), transept façades of Beauvais Cathedral

- Beauvais (Oise), choir and chapels of the Church of Saint-Étienne de Beauvais

- Bourg-en-Bresse (Ain), Royal Monastery of Brou

- Caudebec-en-Caux (Seine-Maritime), Church of Notre-Dame

- L'Épine (Marne), Notre-Dame de l'Épine

- Évreux (Eure), north transept of Évreux Cathedral

- Louviers (Eure), Notre-Dame de Louviers (north and south façade)

- Nantes (Loire-Atlantique), Nantes Cathedral

- Paris, Church of Saint-Séverin

- Paris, Saint-Jacques Tower, bell tower of the former church of Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie

- Pont-de-l'Arche (Eure), Notre-Dame-des-Arts

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), Rouen Cathedral (in part)

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), Church of Saint-Maclou

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), abbey-church of Saint-Ouen

- Rue (Somme), Chapel of Saint-Esprit

- Saint-Nicolas-de-Port (Meurthe-et-Moselle), Basilica of Saint-Nicolas

- Saint-Riquier (Somme), Abbey

- Senlis (Oise), transepts of Senlis Cathedral

- Sens (Yonne), Sens Cathedral (south transept)

- Thann (Haut-Rhin), St Theobald's Church

- Toul (Meurthe-et-Moselle), west façade of Toul Cathedral

- Tours (Indre-et-Loir), Tours Cathedral (west façade)

- Vendôme (Loir-et-Cher), west façade of the Abbaye de la Trinité

- Vincennes (Val-de-Marne), Sainte-Chapelle

Notable examples of civil architecture in France

- Beaune (Côte-d'Or), hospices

- Beauvais (Oise), former episcopal palace

- Bourges (Cher), palace of Jacques-Cœur

- Château de Châteaudun (Eure-et-Loir)

- Paris, Hôtel de Cluny

- Paris, Hôtel de Sens

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), Palais de Justice

Examples of the Flamboyant Gothic Style outside France

- St. Lorenz, Nuremberg (nave ceiling in particular), Germany

- Milan Cathedral, a relatively rare Italian building in the style, which is adopted very fully here

- Vladislav Hall in Prague Castle (vaults), Czech Republic

- Seville Cathedral, Spain

- Capella de Sant Jordi, Palau de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

- Batalha Monastery, Portugal

- Brussels Town Hall, Belgium

- Church of St. Anne, Vilnius, Lithuania

Gallery

Flamboyant window from the last surviving Lusignan palace in Nicosia

Flamboyant window from the last surviving Lusignan palace in Nicosia St Anne's, Vilnius, Lithuania (1500)

St Anne's, Vilnius, Lithuania (1500)St. Vulfran Collegiate Church, west façade, Abbeville Church of Saint-Étienne, interior, chevet, Beauvais

Notre-Dame de l'Épine, west façade, L'Épine Évreux Cathedral, north transept façade, Évreux Abbey-church of St. Ouen, nave elevation, Rouen Chapel of Saint-Esprit, Rue

West façade of Tours Cathedral (towers completed 1547)

West façade of Tours Cathedral (towers completed 1547)

See also

| Look up flamboyant in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Footnotes

- The church was demolished in 1797 following the French Revolution. See Mérimée database

- Content in this section is translated from the existing French Wikipedia article; see its history for attribution.

Citations

- Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), "Flamboyant", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001/acref-9780199674985-e-1822, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 28 June 2020

- Watkin 1986, p. 139.

- Wilson, Christopher (1990). The Gothic cathedral: the architecture of the great church, 1130-1530. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson. p. 252. ISBN 0500341052. OCLC 21206104.

- Ackerman, James S. (1949). ""Ars Sine Scientia Nihil Est" Gothic Theory of Architecture at the Cathedral of Milan". The Art Bulletin. 31 (2): 84–111. doi:10.2307/3047224. ISSN 0004-3079.

- Neagley, Linda Elaine (2007). "Maestre Carlín and 'Proto' Flamboyant Architecture of Rouen (c. 1380-1430)". In Jiménez, Alfonso Martin (ed.). La Piedra Postrera (Simposio Internacional sobre la catedral de Sevilla en el contexto del gótico final). Seville. p. 47-60.

- Kavaler 2012, p. 259–260.

- Adamski, Jakub (2019). "The von der Heyde Chapel at Legnica in Silesia and the Early Phase of the French Flamboyant Style". Gesta. 58 (2): 183–205. doi:10.1086/704253. ISSN 0016-920X.

- "Flamboyant style | Gothic architecture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Schurr, Marc Carel (2010), Bork, Robert E. (ed.), "art and architecture: Gothic", The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662624.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866262-4, retrieved 9 April 2020

- Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), "Gothic", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 9 April 2020

- Lafond, Jean (1973). "Le peintre-graveur E.-Hyacinthe Langlois, «parrain » du style gothique flamboyant". Bulletin de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France. 1971 (1): 313–317. doi:10.3406/bsnaf.1973.8078.

- Hart, Stephen, Medieval Church Window Tracery in England, pp. 1-4, 2010, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, ISBN 1843835339, 9781843835332

- Benton, Janetta Rebold, Art of the Middle Ages, pp. 151-152, 2002, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 0500203504

- Benton, Janetta Rebold (2002). Art of the Middle Ages. New York, N.Y.: Thames and Hudson. p. 191. ISBN 0500203504.

- Stokstad, Marilyn (2019). Medieval Art (Second edition ed.). London: Routledge. p. 345. ISBN 9780367319373.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- Wilson, Christopher (1990). The Gothic cathedral : the architecture of the great church, 1130-1530, with 220 illustrations. New York, N.Y. (500 5th Ave., New York): Thames and Hudson. p. 248. ISBN 0-500-34105-2. OCLC 21206104.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Bork, Robert Odell (2018). Late Gothic architecture : its evolution, extinction, and reception. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-503-56894-2. OCLC 1033899296.

- Wilson, Christopher (1990). The Gothic cathedral : the architecture of the great church, 1130-1530, with 220 illustrations. New York, N.Y.: Thames and Hudson. p. 249. ISBN 9780500276815.

- Fletcher, Banister, Sir, 1866-1953. (1996). Sir Banister Fletcher's a history of architecture. Cruickshank, Dan. (20th ed. ed.). Oxford: Architectural Press. p. 444. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. OCLC 35249531.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- Kavaler 2012, p. 115.

- "Gothic". Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t033435.(subscription required)

- "Chapels 24 | Life of a Cathedral: Notre-Dame of Amiens". projects.mcah.columbia.edu. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Watkin 1986, p. 142.

- Emery, Anthony (2015). Seats of power in Europe during the Hundred Years War : an architectural study from 1330 to 1480. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785701047. OCLC 928751448.

- "Palais de justice". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Neagley, Linda Elaine. (1998). Disciplined exuberance : the Parish Church of Saint-Maclou and late Gothic architecture in Rouen. University Park, Penn: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01716-3. OCLC 36103607.

- Neagley, Linda Elaine (1988). "The Flamboyant Architecture of St.-Maclou, Rouen, and the Development of a Style". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 47 (4): 376. doi:10.2307/990382.

- Kavaler 2012, p. 7–8.

- Meunier 2014, p. 48-49.

- Mocellin, Géraldine (2019). Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye: un millénaire d'histoire. Grenoble: Glénat. p. 122. ISBN 9782344035405.

- Mocellin, Géraldine (2019). Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye: un millénaire d'histoire. Grenoble: Glénat. pp. 70–78. ISBN 9782344035405.

- Monfalcon, Jean Baptiste (1866). Histoire monumentale de la ville de Lyon (in French). A la Bibliothèque de la Ville. pp. 383–384.

- Wolff, Martha (2011). Kings, queens, and courtiers art in early Renaissance France : [exhibition, "France 1500 : entre Moyen Age et Renaissance", Galeries nationales, Grand Palais, Paris, October 6, 2010 - January 10, 2011 ; "Kings, queens, and courtiers : art in early Renaissance France", Art institute of Chicago, February 27 - May 30, 2011]. Art Institute of Chicago. p. 32. ISBN 978030017025-2. OCLC 800990733.

- Babelon, Jean Pierre. (1989). Châteaux de France au siècle de la Renaissance. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012062-X. OCLC 22488607.

- Pérouse de Montclos, Jean-Marie (1992). Guide du patrimoine Centre Val de Loire. Paris: Hachette. p. 436-439. ISBN 2-01-018538-2. OCLC 489587981.

- Bork, Robert Odell (2018). Late Gothic architecture: its evolution, extinction, and reception. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 237–238. ISBN 9782503568942.

- Caron, Sophie (2017). "De la Toscane à la Normandie: Les ateliers de sculpteurs sur le chantier de Gaillon". Une Renaissance en Normandie : le cardinal Georges d'Amboise bibliophile et mécène : [ouvrage publié à l'occasion de l'exposition présentée au Musée d'art, histoire et archéologie d'Evreux du 8 juillet au 22 octobre 2017]. Eds. Calame-Levert, Florence; Hermant, Maxence; Toscano, Gennaro. Éditions Gourcuff Gradenigo. p. 75-76. ISBN 978-2-35340-261-8. OCLC 995099626.

- Watkin 1986, p. 166.

- Watkin 1986, p. 162-3.

- Ducher 2014, p. 54.

- "Corpus of Scottish medieval parish churches: Brechin Cathedral". arts.st-andrews.ac.uk. St Andrews University. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Corpus of Scottish medieval parish churches: Roslin Collegiate Church". arts.st-andrews.ac.uk. St Andrews University. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Curl, James Stevens (2015), Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (eds.), "tracery", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001/acref-9780199674985-e-4762, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 28 June 2020

- Watkin 1986, p. 152.

- Watkin 1986, p. 154.

- Hughes, Robert (1993). Barcelona. New York: Vintage Books. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-307-76461-4. OCLC 774576886.

- Carbonell i Buades, Marià (2008). "De Marc Safont a Antoni Carbonell: la pervivencia de la arquitectura gótica en Cataluña". Artigrama. 23: 97-148. S2CID 172385423.

- Watkin 1986, p. 174-75.

- Watkin 1986, p. 174-175.

- Watkin 1986, p. 176.

- Watkin 1986, p. 177.

- Białostocki, Jan (1966). "Late Gothic: Disagreements About the Concept". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 29 (1): 94. doi:10.1080/00681288.1966.11894934. ISSN 0068-1288.

- Ducher 2014, p. 52.

- Ducher 2014, p. 52-3.

- Kavaler 2012, p. 116.

- Neagley, Linda Elaine (2008). "Late Gothic Architecture and Vision: Representation, Scenography, and Illusionism". In Reeve, Matthew M. (ed.). Reading Gothic Architecture. Turnhout: Brepols. p. 44-50. ISBN 9782503525365. OCLC 154760861.

- Kavaler 2012, p. 122.

- Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 37.

- Ducher 2014, p. 52-53.

References

- Ackerman, James S. (1949). "'Ars Sine Scientia Nihil Est' Gothic Theory of Architecture at the Cathedral of Milan". The Art Bulletin. 31 (2): 84–111. doi:10.2307/3047224.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adamski, Jakub (2019). "The von der Heyde Chapel at Legnica in Silesia and the Early Phase of the French Flamboyant Style". Gesta. 58 (2): 183–205. doi:10.1086/704253.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Babelon, Jean Pierre (1989). Châteaux de France au siècle de la Renaissance. Paris: Flammarion/Picard. ISBN 208012062X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bechmann, Roland (2017). Les Racines des Cathédrales (in French). Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-90651-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beltrami, Costanza (2016). Building a crossing tower: a design for Rouen Cathedral of 1516. London: Paul Holberton Publishing. ISBN 9781907372933.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Benton, Janetta (2002). Art of the Middle Ages. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500203507.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Białostocki, Jan (1966). "Late Gothic: Disagreements About the Concept". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 29 (1): 76–105. doi:10.1080/00681288.1966.11894934.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bork, Robert (2018). Late Gothic Architecture: Its Evolution, Extinction, and Reception. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 9782503568942.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bos, Agnès (2003). Les églises flamboyantes de Paris: XVe-XVIe siècles. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708407022.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bottineau-Fuchs, Yves (2001). Haute-Normandie Gothique: Architecture Religieuse. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708406179.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carbonell i Buades, Marià (2008). "De Marc Safont a Antoni Carbonell: la pervivencia de la arquitectura gótica en Cataluña". Artigrama. 23: 97–148. S2CID 172385423.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caron, Sophie (2017). "De la Toscane à la Normandie: Les ateliers de sculpteurs sur le chantier de Gaillon". In Calame-Levert, Florence; Hermant, Maxence; Toscano, Gennaro (eds.). Une Renaissance en Normandie: le cardinal Georges d'Amboise bibliophile et mécène: [ouvrage publié à l'occasion de l'exposition présentée au Musée d'art, histoire et archéologie d'Evreux du 8 juillet au 22 octobre 2017]. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo. pp. 70–76. ISBN 9782353402618.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Michael T. (1983). "'Troys Portaulx et Deux Grosses Tours': The Flamboyant Façade Project for the Cathedral of Clermont". Gesta. 22 (1): 67–83. doi:10.2307/766953.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ducher, Robert (2014). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Emery, Anthony (2016). Seats of Power in Europe During the Hundred Years War: an architectural study from 1330 to 1480. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785701030.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guillouët, Jean-Marie (2019). Flamboyant architecture and medieval technicality (c. 1400-c. 1530): a micro-history of the rise of artistic consciousness at the end of Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 9782503577296.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamon, Étienne (2011). Une capitale flamboyante: la création monumentale à Paris autour de 1500. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708409095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hart, Stephen (2012). Medieval church window tracery in England. Woodbridge; Rochester: The Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843835332.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, Robert (1993). Barcelona. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780307764614.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kavaler, Ethan Matt (2012). Renaissance Gothic: Architecture and the Arts in Northern Europe, 1470-1540. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300167924.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mignon, Olivier (2017). Architecture du Patrimoine Française - Abbayes, Églises, Cathédrales et Châteaux (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-7611-5.

- Meunier, Florian (2014). Le Paris du Moyen Âge. Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-6217-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2015). Martin & Pierre Chambiges: architectes des cathédrales flamboyantes. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708409750.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mocellin, Géraldine, ed. (2019). Saint-Antoine l'abbaye: un millénaire d'histoire. Grenoble: Glénat. ISBN 9782344035405.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neagley, Linda Elaine (1988). "The Flamboyant Architecture of St.-Maclou, Rouen, and the Development of a Style". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 47 (4): 374–396. doi:10.2307/990382.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (1998). Disciplined Exuberance: The Parish Church of Saint-Maclou and Late Gothic Architecture in Rouen. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271017167.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2008). "Late Gothic Architecture and Vision: Re-presentation, Sceneography and Illusionism". In Reeve, Matthew M. (ed.). Reading Gothic Architecture. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 37–56. ISBN 9782503525365.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pérouse de Montclos, Jean-Marie (1992). Centre: Val de Loire. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 9782010185380.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Gisserot. ISBN 9-782877-474658.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reveyron, Nicolas; Tuloup, Jean-Sébastien, eds. (n.d.). Primatial Church of Saint-John-the-Baptist, Cathedral of Lyon. Lyon: Impr. Beau'Lieu. OCLC 943383702.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanfaçon, Roland (1971). L'architecture Flamboyante en France. Quebec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval. OCLC 1015901639.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours. Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédrales Gothiques - un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Wilson, Christopher (1990). The Gothic Cathedral: the architecture of the great church. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500341056.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)