Extremal graph theory

Extremal graph theory is a branch of mathematics that studies how global properties of a graph influence local substructure.[1] It encompasses a vast number of results that describe how do certain graph properties - number of vertices (size), number of edges, edge density, chromatic number, and girth, for example - guarantee the existence of certain local substructures.

One of the main objects of study in this area of graph theory are extremal graphs, which are maximal or minimal with respect to some global parameter, and such that they contain (or do not contain) a local substructure- such as a clique, or an edge coloring.

Examples

Extremal graph theory can be motivated by questions such as the following:

Question 1. What is the maximum possible number of edges in a graph on vertices such that it does not contain a cycle?

If a graph on vertices contains at least edges, then it must also contain a cycle. Moreover, any tree with vertices contains edges and does not contain cycles; trees are the only graphs with edges and no cycles. Therefore, the answer to this question is , and trees are the extremal graphs.[2]

Question 2. If a graph on vertices does not contain any triangle subgraph, what is the maximum number of edges it can have?

Mantel's Theorem answers this question – the maximal number of edges is . The corresponding extremal graph is a complete bipartite graph on vertices, i.e., the two parts differ in size by at most 1.

A generalization of Question 2 follows:

Question 3. Let be a positive integer. How many edges must there be in a graph on vertices in order to guarantee that, no matter how the edges are arranged, the clique can be found as a subgraph?

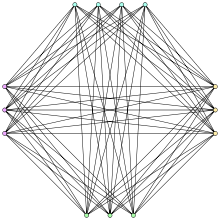

The answer to this question is and it is answered by Turán's Theorem. Therefore, if a graph on vertices is -free, it can have at most

many edges; the corresponding extremal graph with that many edges is the Turán graph, shown in the figure above. It is the complete join of independent sets (with sizes as equal as possible – such a partition is called equitable).

The following question is a generalization of Question 3, where the complete graph is replaced by any graph :

Question 4. Let be a positive integer, and any graph on vertices. How many edges must there be in a graph on vertices in order to guarantee that, no matter how the edges are arranged, is a subgraph of ?

This question is mostly answered by the Erdős–Stone theorem. The main caveat is that for bipartite , the theorem does not satisfactorily determine the asymptotic behavior of the extremal edge count. For many particular (classes of) bipartite graphs, determining the asymptotic behavior remains an open problem.

Several foundational results in extremal graph theory answer questions which follow this general formulation:

Question 5. Given a graph property , a parameter describing a graph, and a set of graphs , we wish to find the minimal possible value such that every graph with has property . Additionally, we might want to describe graphs which are extremal in the sense of having close to but which do not satisfy the property .

In Question 1, for instance, is the set of -vertex graphs, is the property of containing a cycle, is the number of edges, and the cutoff is . The extremal examples are trees.

History

Mantel's Theorem (1907) and Turán's Theorem (1941) were some of the first milestones in the study of Extremal graph theory.[3] In particular, Turán's theorem would later on become a motivation for the finding of results such as the Erdős-Stone-Simonovits Theorem (1946).[1] This result is surprising because it connects the chromatic number with the maximal number of edges in an -free graph. An alternative proof of Erdős-Stone-Simonovits was given in 1975, and utilised the Szemerédi regularity lemma, an essential technique in the resolution of extremal graph theory problems.[3]

Density results and inequalities

A global parameter which has an important role in extremal graph theory is subgraph density; for a graph and a graph , its subgraph density is defined as

.

In particular, edge density is the subgraph density for :

The theorems mentioned above can be rephrased in terms of edge density. For instance, Mantel's Theorem implies that the edge density of a triangle-free subgraph is at most . Turán's theorem implies that edge density of -free graph is at most .

Moreover, the Erdős-Stone-Simonovits theorem states that

where is the maximal number of edges that an -free graph on vertices can have, and is the chromatic number of . An interpretation of this result is that the edge density of an -free graph is asymptotically .

Another result by Erdős, Rényi and Sós (1966) shows that graph on vertices not containing as a subgraph has at most the following number of edges.

Minimum degree conditions

The theorems stated above give conditions for a small object to appear within a (perhaps) very large graph. Another direction in extremal graph theory is looking for conditions that guarantee the existence of a structure that covers every vertex. Note that it is even possible for a graph with vertices and edges to have an isolated vertex, even though almost every possible edge is present in the graph. Edge counting conditions give no indication as to how the edges in the graph are distributed, leading to results which only find bounded structures on very large graphs. This provides motivation for considering the minimum degree parameter, which is defined as

A large minimum degree eliminates the possibility of having some 'pathological' vertices; if the minimum degree of a graph G is 1, for example, then there can be no isolated vertices (even though G may have very few edges).

An extremal graph theory result related to the minimum degree parameter is Dirac's theorem, which states that every graph with vertices and minimum degree at least contains a Hamilton cycle.

Another theorem[3] says that if the minimum degree of a graph is , and the girth is , then the number of vertices in the graph is at least

.

Some open questions

Even though many important observations have been made in the field of extremal graph theory, several questions still remain unanswered. For instance, Zarankiewicz problem asks what is the maximum possible number of edges in a bipartite graph on vertices which does not have complete bipartite subgraphs of size .

Another important conjecture in extremal graph theory was formulated by Sidorenko in 1993. It is conjectured that if is a bipartite graph, then its graphon density (a generalized notion of graph density) is at least .

See also

- Ramsey theory

- Graph density inequalities

- Forbidden subgraph problem

- Dependent random choice

Notes

- Diestel 2010

- Bollobás 2004, p. 9

- Bollobás 1998, p. 104

References

- Bollobás, Béla (2004), Extremal Graph Theory, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-43596-1.

- Bollobás, Béla (1998), Modern Graph Theory, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 103–144, ISBN 978-0-387-98491-9.

- Diestel, Reinhard (2010), Graph Theory (4th ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 169–198, ISBN 978-3-642-14278-9, archived from the original on 2017-05-28, retrieved 2013-11-18.

- M. Simonovits, Slides from the Chorin summer school lectures, 2006.