Evacuation in the Soviet Union

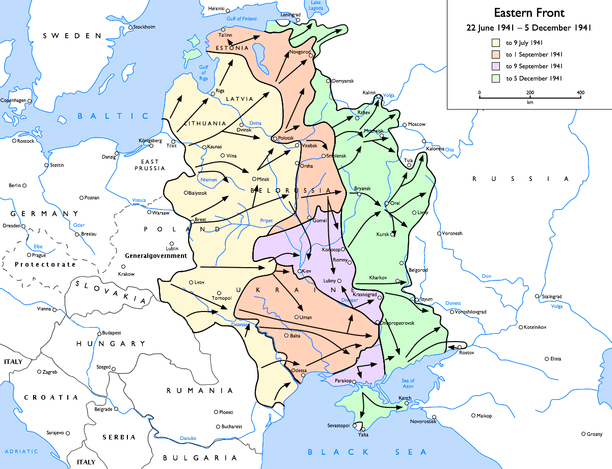

Evacuation in the Soviet Union was the mass migration of western Soviet citizens and its industries eastward as a result of Operation Barbarossa, the German military invasion of June 1941. Nearly sixteen million Soviet civilians and over 1,500 large factories were moved to areas in the middle or eastern part of the country by the end of 1941.[1] Along with the eastern exodus of civilians and industries, other unintended consequences of the German advances saw the execution of previously held western state civilians by Soviet NKVD units, the removal of Lenin's body from Moscow to Tyumen, and the relocation of the Hermitage Museum collection to Sverdlovsk, Kuybyshev, the alternative capital of the Soviet Union 1941-1943. Soviet towns and cities inland or in the east received the bulk of the new refugees and high priority war factories, as locations such as the Siberian city of Novosibirsk, received more than 140,000 refugees and many factories due to its location away from the front lines. Despite early German successes in seizing control of large swaths of the western USSR throughout 1943, and semi-prepared contingency plans by the Soviets in their mobilization plans to the east, Soviet industries would eventually outpace the Germans in arms production, culminating in 73,000 tanks, 82,000 aircraft and nearly 324,000 artillery pieces being dispersed throughout the Red Army in their fight against the Axis Powers by 1945.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Population transfer in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Policies |

| Peoples |

|

| Operations |

| WWII POW labor |

| Massive labor force transfers |

|

Governmental policy

With Stalin and the Communist Party's Central Committee knowing that Hitler would eventually turn on the Soviet Union, there were plans made before Operation Barbarossa was launched to begin the evacuation as a precaution to Nazi assault. A Party man in Moscow involved in that city's evacuation committee, Vasilii Prokhorovich Pronin, submitted a plan that would have removed some one million Muscovites, but it was rejected by Stalin. It would have to wait for the actual invasion before the Party enacted any real plan for evacuation.[3]

Two days after the German invasion of June 24, 1941, the Party created an Evacuation Council in an attempt to create a procedure for the coming evacuation of Soviet citizens living close to the Eastern Front. It identified cities along major train routes of the USSR in which people could be removed and taken quickly because they were easily accessible by railroad. As of September, three months following the invasion by the Nazis, the Evacuation Council had 128 centers identified and operating. Prominent city centers that received evacuated citizens (as well as other resources and industry) include Kirov, Iaroslavl, Gorky, Ufa, Sverdlovsk, Cheliabinsk, and Kuibyshev.[3]

Further measures were instated by the Party in order to help dispersed evacuees settle in to life in their new location. Evacuees new to a city were instructed to contact the local authorities so that they could be accounted for. Following this, they received a certificate declaring their evacuee status and allowing them to receive lodgings, food rations, and temporary employment. Evacuees were told that they were allowed to bring personal belongings with them as long as it didn't hinder the authorities' abilities to get them from the evacuated site to the refuge center. Family members' belongings were not to exceed 40 kilograms in weight.[3]

Another instruction from the Central Committee during the months of August and September was for regional governments to build temporary housing for the newcomers if there was not enough existing in that region already. This preceded the measure enacted in November when the Party agreed to establish an Evacuation Administration, thus taking the power out of the hands of regional authorities and centralizing it within the Communist Party. This led to offices of the said agency popping up throughout the evacuation center cities and regions so as to better regulate and look after the dispersed evacuees. The agents of the Evacuation Administration were in charge of making sure that the evacuees were being well taken care of in their new locations. An added concern, in addition to housing, employment, and food, was health care and child care. As of the early months of 1942, still under the one-year mark of being at war with Germany, the government in Moscow had already spent three billion rubles on the evacuation effort.[3]

Deportation as a part of the evacuation

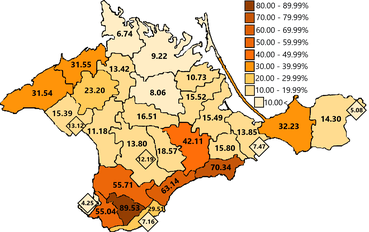

Another civilian population concern that came up after the German invasion was with a group of Soviet civilians who became a part of the evacuation, but were classified as deportees instead of evacuees. The Party feared that these deportees would switch loyalties and fight on the German side. The first of this process, that eventually affected as many as 3.3 million people made up of 52 different nationalities, was a decree published in 1941 that dealt with the removal of Volga Germans that sent them to Siberia and Kazakhstan, far away from the front lines of fighting between the Wehrmacht and Soviets. The rest of the evacuation of suspected-disloyal nationalities took place later in the war during the years of 1943 and 1944.[4] Because the Volga Germans were one of two deported nationalities (the other being the Crimean Tatars) that were never returned to their homeland after the war had ended, modern historians interpret this as being within the parameters of an ethnic cleansing.[5]

The Crimean Tatars are an exception to the rule set by the Party that deportation occurred because they suspected questionable nationalities would be pro-German. The Tatars were a Muslim minority and the Party suspected that they would choose their religion over the state.[6] Historians often trace the Soviet persecution and elimination of the Tatars in Crimea even further back to the inner war years after the establishment of the Soviet state. It is reported that from 1917 to 1933 an estimated half of the Crimean Tatar population was eliminated, either by death or relocation.[7]

The deported nationalities generally came from regions close to the Eastern Front and were settled in Kazakhstan and Central Asia during the war.[5] In 1956, over a decade after the end of the Second World War, all of the groups besides the Volga Germans and the Crimean Tatars, were resettled in their native lands. Khrushchev would absolve all blame from the Germans during his time in command of the Communist Party. It is believed that they weren't permitted for resettlement because the area had already been settled by other Soviet civilians in the time since the war's end.[4] The same belief is expressed in regards to why the Crimean Tatars were not granted resettlement as a part of the 1956 orders. However, the Crimean Tatar National Movement Organization organized during perestroika in the 1980s finally received word from the Soviet government that their people could return to Crimea.[8] Since then, some 250,000 Crimean Tatars have returned and settled in what is now the independent Ukraine, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Deported nationalities with year in which deportation occurred[9]

- 1941: Volga Germans

- 1943: Karachai

- 1943: Kalmyks

- 1944: Balkars

- 1944: Chechens and Ingushi

- 1944: Crimean Tatars

- 1944: Greeks

- 1944: Meskhetian Turks

Evacuation of industry

The speed of the initial German advance threatened not only Soviet territories and factories, civilian and military, but wholesale collapse of the nation's civilian economy.[10] Even with 1930s contingency plans and the formation, in 1941, of evacuation committees, such as the Council for Evacuation and the State Department Committee (GKO), most evacuations were handled by local Soviet organizations that dealt with the industrial movements just ahead of impending German attacks.

Short sighted preparation in the overall mobilization of the western front led many in these councils to scour Moscow libraries for any resources pertaining to evacuations during the first World War.[11][2] Local committees eventually used the Five-Year Plan structure with 3,000 agents controlling the movement. Evacuation of industrial plants began in August 1941 and continued until the end of the year.[12][10]

The GKO oversaw the relocation of more than 1500 plants of military importance to areas such as the Urals, Siberia, and Central Asia. These areas offered safety to its inhabitants due to its isolated locations that were not in reach of damaging Axis airstrikes, and they offered Soviet industries with a mass quantity of resources to field the factories and plants associated with the war effort. The Urals in central Russia fielded an impressive array of heavy iron and steel factories as well as agriculture and chemical plants. The Siberian industries relied on their coal mines and copper deposits in the Kuznetzk coal basin for continuing the support of the Soviet war machine.[13]

But evidence shows that some evacuations, the transfer of machine tools and skilled workers to “shadow factories” in the east, began much earlier. The U.S. military attaché reported significant transfers of machines and men from the Moscow area to the east in late 1940 and early 1941. The rapid growth in production early in 1942 suggests that the evacuation started in 1940.[12]

Evacuation of civilians

The word evacuation or evakuatsiia in 1941 was a somewhat new word that some described as "terrible and unaccustomed". For others, it was simply not used. "Refugee" or bezhenets was far too familiar given the country's history of war. During World War II refugee was replaced by evacuees.The shift in wording showed the government's resignation to the displacement of its citizens. The reasons for controlling the displaced population varied.[14] Despite some preferring to consider themselves evacuees the term referred to different individuals. Some were of the “privileged elite" class. Those who fell under this category were scientists, specialized workers, artists, writers and politicians. These elite individuals were evacuated to the rear of the country. The other portion of the evacuated were met with a suspicious eye. The evacuation process despite the Soviets best efforts, was far from organized. The state considered the majority of those heading east as suspicious. Since a large majority of the population were self evacuees they had not been assigned a location for displacement. Officials feared the disorder made it easy for deserters to flee. Evacuees who did not fall under the “privileged elite” title were are also suspected of potentially contaminating the rest of the population both epidemically and ideologically.[15]

From the beginning of the 20th century Russia had been engulfed in wars.[16] If this war-bred society was taught anything it was the importance of mobilizing both its industry as well as civilian population.[17] The Russian Civil War and World War 1 gave the Bolsheviks the experience to shape their future evacuation strategies.[18] Preparation for future war started in the early 1920s but it wasn't till the war scare of 1927 that they started developing defensive measures, these measures included evacuation policies. These policies were not formed as a humanitarian effort but as a way for the country to defend itself. They needed to avoid the past issues such as: hindrance of military movement, spread of disease, and demoralizing of units as well as strains on the economy.[19] The Council of Labor and Defense was in charge of drafting these policies along with other Soviet administrations[20]

German Operation Barbarossa of 1941 resulted in millions of Russian evacuees. The exact number is hard to approximate since many evacuated themselves rather than by the states directive.[21] Some put the number at about sixteen and a half million.[22] One of the most welcome sights for refugees during the evacuations was Tashkent, capital of Uzbekistan, which eventually housed tens of thousands of refugees. However, due to the vast number of refugees the train stations were overcrowded and the distribution of train tickets could take days.[23] Even with the war drawing to an end evacuee's who were desperate to go back home where not granted permission. The re-evacuation policy was written around those not working in industry. These citizens lost their residence to their city of origin, therefore were not part of the re-evacuation process. Anybody who tried to return without consent faced jail time. Despite many roadblocks and issues the Soviet state managed to do what no other European country could: evacuating millions of its citizens to the safety of the rear.[24]

With a shortage of labor, the Commissariat of Justice in conjunction with the Council of People's Commissars forced evacuees to work in enterprises, organizations and on collective farms to help the war effort. Those chosen for the labor force were those deemed as socially unproductive. People who did not work for a set wage such as artists, writers and artisans were excluded from this new decree. Problems did arise with workers motivation to work. Some argued that upon returning to their homes that they found themselves unhappy with the wages they would receive, arguing the government would give almost as much in subsidies if they didn't work at all.[25]

As winter approached and the war intensified around Moscow, the Moscow Oblast Committee of the Communist Party and the Executive Committee of the Moscow Oblast Council found it of great importance to evacuate women and children from the suburbs. They requested to the Evacuation Council of the Soviet Council of Peoples Commissariats was as follows 300,000 • Assigned destinations • Peoples Commissariat of Transportation was to transport the evacuees from the Moscow suburbs. [26][27] When it came to the evacuation of children, officials were ill-prepared for the task. The children who were transported to Moscow were done so in barges lacking basic safety measures within their design, most notably side railings. Subsequently, children would often be known to fall over board. First-hand accounts from children state that the boats had been previously used for the transportation of flour and other agricultural goods, opposed to passengers. Water was rarely given and when it was they were only allowed a few gulps from what was described as “putrid.” Those aboard slept on crowded floors in abhorrently crowded conditions. On one account, a child wrote to his parents that he was eating well. He wrote about having bread and tea for breakfast, and for lunch he would eat cabbage soup.

Jewish families in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union had added nearly 2,000,000 Jews to its population between 1939 and 1940.[28] Many of these came from recently annexed Poland, but they came from other areas as well. After the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact the USSR and Germany each took over large portions of former countries, including Poland, the Baltic region, and Romania. In Romania, the USSR took mostly eastern portions, including Bessarabia and northern Bukovina. It is estimated that around 250,000 Jews were living in Bessarabia and Bukovina at the time.[29] Another 120,000 Jews flowed into the newly annexed Bessarabia and Bukovina from the now Nazi-occupied Romania.[29] By the late spring of 1941 there were as many as 415,000 Jews living in Soviet controlled Bessarabia and Bukovina. Around 10,000 of these newly Soviet Jews were deported into the interior of Russia for various reasons, many of them ending up in the Red Army.[29] There is evidence that the Soviet government made some efforts to incorporate these displaced Jewish citizens into Soviet society. The creation of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee is one example of this.[28] Many Jews living in the now Nazi occupied parts of Romania and Poland were not keen to move to Russia, whose policies toward religion did not favor them. Many underestimated the dangers of the impending Nazi war machine and paid the ultimate price. Many Jews that fled into Russia from Germany had a saying, "better Stalin than Hitler"[28] There were as many as 3,000,000 Jews killed in The Soviet Union during World War II by the Einsatzgruppen.[28]

When Germany invaded Russia in 1941 most of the Jewish citizens living in these regions were murdered by the Nazis but some Jewish families fled east into Russia. While the Soviet Union did not keep records specifically relating to Jews, it is estimated that 300,000 Soviet citizens were evacuated from Moldavia to places like Kazakhstan.[29] It is unknown how many of these citizens were Jewish. In February 1942 there were as many as 45,000 displaced Jewish citizens from the Moldavian region living in Uzbekistan.[29] There were around 80,000 - 85,000 Jews from the Moldavian region displaced to each of the other Soviet states by early 1942.[29]

Lenin's body

In the face of the German advance and amidst the evacuations of industry and civilians, the Politburo made the decision to evacuate the embalmed body of Vladimir Lenin from its mausoleum in Red Square, where it had been on display since 1924.[30]

Lenin's body was removed in secret and sent far from the front lines and away from any industrial areas threatened by German bombers. The city of Tyumen, approximately 2,500 kilometers east of Moscow, was its chosen destination. In June 1941 Lenin's body was encased in paraffin and placed in a wooden coffin that was then nested inside a larger wooden crate. Along with the body were sent chemicals and implements necessary for the continued preservation of the body. The crate was placed on a dedicated train secured by a selected group of Kremlin Guards. The body had its own private car and a personal guard around the clock. Additional soldiers were posted along the tracks and stations on the train's route east.[31]

On arrival in Tyumen the body was housed in a dilapidated building on the campus of the Tyumen Agricultural Institute. The conditions necessitated the acquisition of additional chemicals and distilled water from the city of Omsk, a further 600 kilometers east of Tyumen.[32]

Lenin's body was returned to Moscow in April 1945.[33]

Notes and references

- Manley, Rebecca, and Rebecca Manley. “To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War.” To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, Cornell University Press, 2009, p.7-8

- Freeze, Gregory L.. Russia, A History, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.330

- Holmes, Larry E. Stalin's World War II Evacuations: Triumph and Troubles in Kirov. University of Kansas Press. ISBN 9780700623969.

- McCauley, Martin (2003). Stalin and Stalinism, Third Edition. Pearson Education. p. 132.

- "Deportation of Minorities". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. 2015-06-18. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- "Orthodox Patriarch Appointed". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. 2015-06-18. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- "The Crimean Tatars: A Primer". The New Republic. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Institutional Development of the Crimean Tatar National Movement". www.iccrimea.org. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- McCauley, Martin (2003). Stalin and Stalinism, Third Edition. Pearson Education. pp. 72–73.

- Harrison, Mark. Soviet and East European Studies, Soviet Planning in Peace and War 1938-1945, Cambridge University Press, 1985, p.79

- Harrison, Mark. Soviet and East European Studies, Soviet Planning in Peace and War 1938-1945, Cambridge University Press, 1985, p.79

- Dunn, Walter S. Jr., The Soviet Economy and the Red Army 1930-1945, Praeger Publishers, 1995, p.32

- Gregory L.. Russia, A History, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.330

- 4. Manley, Rebecca, and Rebecca Manley. “To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War.” To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, Cornell University Press, 2009, p.7-8

- 18. Manley, Rebecca. "The Perils of Displacement: The Soviet Evacuee between Refugee and Deportee." Contemporary European History, vol. 16, no. 04, Nov. 2007, p. 499-500., doi:10.1017/s0960777307004146

- 1. Manley, Rebecca, and Rebecca Manley. “To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War.” To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, Cornell University Press, 2009, p. 13.

- .Geyer, Michael, et al. “Ch 9/State of Expectation .” Beyond Totalitarianism Stalinism and Nazism Compared, Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 362. War by any means

- 3. M. M. Gorinov, V. N. Parkhachev, and A. N. Ponomarev, eds. Moskva prifrontovaia, 1941 1942: Arkhivnye dokumenty imaterialy. (Moscow: Izdatel stvo ob edineniia Mosgorarkhiv, 2001), p. 254.

- 5. Manley, Rebecca, and Rebecca Manley. “To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War.” To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, Cornell University Press, 2009, p.13

- 6. Manley, Rebecca, and Rebecca Manley. “To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War.” To the Tashkent Station Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, Cornell University Press, 2009, p.13

- 15. Harrison, Mark. Soviet planning in peace and war, 1938-1945. Cambridge [U.K.] ; Cambridge University Press, c1985. hdl:2027/heb.05435.0001.001. pg 71-72

- 16. Manley, Rebecca. "The Perils of Displacement: The Soviet Evacuee between Refugee and Deportee." Contemporary European History, vol. 16, no. 04, Nov. 2007, p. 495., doi:10.1017/s0960777307004146.

- To the Tashkent Station. Evacuation and survival in the Soviet Union at war, by Rebecca Manley, Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press, 2009

- 20. Manley, Rebecca. “The Perils of Displacement: The Soviet Evacuee between Refugee and Deportee.” Contemporary European History, vol. 16, no. 04, Nov. 2007, p. 509., doi:10.1017/s0960777307004146

- 19. Manley, Rebecca. “The Perils of Displacement: The Soviet Evacuee between Refugee and Deportee.” Contemporary European History, vol. 16, no. 04, Nov. 2007, p. 504-505., doi:10.1017/s0960777307004146

- 13. M. M. Gorinov, V. N. Parkhachev, and A. N. Ponomarev, eds. Moskva prifrontovaia, 1941 1942: Arkhivnye dokumenty i materialy. (Moscow: Izdatel stvo ob edineniia Mosgorarkhiv, 2001), p. 254.

- M. M. Gorinov, V. N. Parkhachev, and A. N. Ponomarev, eds. Moskva prifrontovaia, 1941 1942: Arkhivnye dokumenty i materialy. (Moscow: Izdatel stvo ob edineniia Mosgorarkhiv, 2001), p. 161. 15.

- Asher, Harvey (14 November 2003). "The Soviet Union, the Holocaust, and Auschwitz". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 4 (4): 886–912. doi:10.1353/kri.2003.0049.

- Kaganovitch, A. (2013). "Estimating the Number of Jewish Refugees, Deportees, and Draftees from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina in the Non-Occupied Soviet Territories". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 27 (3): 464–482. doi:10.1093/hgs/dct047.

- Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Moscow 1941 : a city and its people at war (Rev. and updated paperback ed.). London: Profile Books. p. 94. ISBN 9781861977748.

- Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Moscow 1941 : a city and its people at war (Rev. and updated paperback ed.). London: Profile Books. p. 94. ISBN 9781861977748.

- Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Moscow 1941 : a city and its people at war (Rev. and updated paperback ed.). London: Profile Books. pp. 94–95. ISBN 9781861977748.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2013). Tombs of the great leaders : a contemporary guide. London: Reaktion Books, Limited. p. 42. ISBN 9781780232003.