Eureka Iron & Steel Works

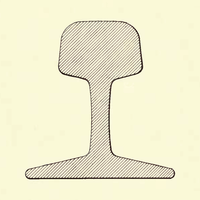

The Eureka Iron & Steel Works (also known as Eureka Iron Works, Eureka Iron and Steel Company and Wyandotte Mills) was an American iron and steel company in Wyandotte, Michigan. It started in 1853 with the discovery of unusually high-quality iron ore in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. A group of businessmen in the Detroit area figured this could be a profitable enterprise to manufacture iron and steel so pooled together funds to form a new company. It made the first commercially available steel in America. One of the first uses for this steel was tracks for railroads. It was in business until 1892.

| Industry | manufacturing |

|---|---|

| Fate | sold in 1892 |

| Founded | October 15, 1853 in Detroit, US |

Key people | Eber Brock Ward Thomas W. Lockwood George S. Thurber |

| Products | iron and steel railroad tracks |

Founding

Philip Thurber, a businessman from the Detroit area, took a summer vacation in Michigan's Upper Peninsula in 1853. The discovery of iron ore in the Marquette area where he was vacationing piqued his interest. He tested samples and found them to be of unusually high quality, so he decided to develop a new enterprise using this iron ore. With a group of investors, the Eureka Iron Works company was then organized on October 15, 1853.[1] The new company consisted of ten stockholders. Eber Brock Ward, a ship captain, became the president.[2] Thomas W. Lockwood was its treasurer and George S. Thurber was its secretary.[2] The new company had 20,000 shares valued at twenty-five dollars each.[2]

The Eureka Iron Works company looked around the Detroit area for a suitable piece of land for a foundry. The company decided on a 2,200-acre (890 ha) plot owned by Major John Biddle as a summer estate called "Wyandotte." The land was purchased at $20 per acre and became the village of Wyandotte on December 12, 1854. It is today the city of Wyandotte, Michigan. The plot was chosen because its two miles (3.2 km) of river frontage could be used to receive iron ore by ship from the Lake Superior region of the Upper Peninsula. The land also had timber that was used in making charcoal and was close to quarries supplying limestone, a product needed to make iron and steel.[3] In 1855, the company built a complex of buildings for the company and workmen. A blast furnace and a bar mill known as the Wyandotte Rolling Mill were also constructed as a nearby spin-off company with the same owners as the Eureka Iron Works. These two foundries were known as the Wyandotte Mills.[4]

Steel rails

The Eureka Iron Works company started manufacturing inexpensive steel ingots in 1864.[5] The ingots were made from poured molten steel from Bessemer converters. These converter vessel machines developed steel from molten iron in a heating process that added alloys that improved the strength of the steel. The ingot blocks were about 20 inches (510 mm) square and 7 feet (2.1 m) long. The ingots were shipped to rolling mills, where they were placed into furnaces and reheated to a white heat. They were then processed through roller machinery that formed steel rails 160 feet (49 m) long. These long rails were cut into standard lengths as the final product for constructing railroad tracks.[6]

The first Bessemer steel rails ever made in the United States came from the North Chicago Rolling Mill on May 24, 1865. This mill was started by Ward in 1857 to make iron rails. The experimental steel ingots made at the Eureka Iron & Steel Works company at Wyandotte, also controlled by Ward, were shipped to Chicago to be shaped into steel rails since the mill there was already equipped for such production. Six of these first rails made were laid in the track of a railroad running out of Chicago and were still in place ten years later.[7] This was the first time commercial steel was made in America.[3][8] Steel rails in 1865, at the beginning of manufacturing, sold for $120 a ton. As steel rail production increased at various mills, the average market price settled at $34 per ton.[6]

Demise

The Wyandotte Rolling Mill company was successful in the 1860s, but began to decline after the death of Ward in 1875. It failed in 1877 and the Eureka Iron & Steel Works company took over its operations.[4] The Rolling Mill company was not originally designed for steel production, and instead of changing methods the president of the company decided to move steel production to Chicago. Another reason for the demise of the company was that it consumed 50,000 cords of wood a year for charcoal, an ingredient needed to make iron and steel. When the company ran out of local timber, the cost of shipping charcoal cut into profits. Eventually, there was little need for iron as most merchants preferred steel, which was available from several companies at competitive prices.[9]

The Wyandotte Rolling Mills went bankrupt in 1879 and its adjacent land was taken over by the Eureka Iron & Steel Works through a foreclosure process.[10] The Eureka Iron & Steel Works was reorganized in 1883 and became the Eureka Iron and Steel Company.[4] In 1888, a boiler explosion killed three workmen and injured several others, contributing to the company's demise.[11] The company finally went out of business in 1892. The steel manufacturing equipment and factory land were sold at auction.[12]

References

- "Encyclopedia of Detroit / Eureka Iron Works". Detroit Historical Society. 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- Farmer 1890, p. 1276.

- Woodford 2001, p. 80.

- Farmer 1890, p. 1277.

- "Fete Marks Inception of First Steel Ingots". Lansing State Journal. Lansing, Michigan. July 5, 1958. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com

- "Steel Rails". Kansas City Daily Gazette. Kansas City, Kansas. October 16, 1888. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

- Geological 1895, p. 226.

- "First Steel Ship on Great Lakes". The Times Herald. Port Huron, Michigan. November 14, 1965. p. 24 – via Newspapers.com

- "Wyandotte Booming in Downriver Hub". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. September 28, 1952. p. 29 – via Newspapers.com

- "Bankrupt Sale". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. February 20, 1879. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com

- "Detroit, June 1". Harrisburg Daily Independent. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. June 1, 1888. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

- "Auction Sale / Eureka Iron & Steel Works". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. November 15, 1892. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com

Sources

- Farmer, Silas (1890). History of Detroit and Wayne County and Early Michigan, Volume 2. S. Farmer & Company. OCLC 43603346.

- Geological, Survey (1895). Mineral Resources of the United States, Part 1. U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 637770704.

- Woodford, Arthur M. (2001). This is Detroit 1701–2001. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814329144.