Eurasian harvest mouse

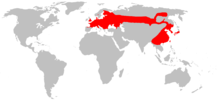

The harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) is a small rodent native to Europe and Asia. It is typically found in fields of cereal crops, such as wheat and oats, in reed beds and in other tall ground vegetation, such as long grass and hedgerows. It has reddish-brown fur with white underparts and a naked, highly prehensile tail, which it uses for climbing. It is the smallest European rodent; an adult may weigh as little as 4 grams (0.14 oz). It eats chiefly seeds and insects, but also nectar and fruit. Breeding nests are spherical constructions carefully woven from grass and attached to stems well above the ground.

| Eurasian harvest mouse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Muridae |

| Genus: | Micromys |

| Species: | M. minutus |

| Binomial name | |

| Micromys minutus (Pallas, 1771) | |

| |

| Distribution of Eurasian harvest mouse | |

History

The genus Micromys most likely evolved in Asia and is closely related to the long-tailed climbing mouse (Vandeleuria) and the pencil-tailed tree mouse (Chiropodomys).[2] Micromys first emerged in the fossil record in the late Pliocene, with Micromys minutus being recorded from the Early Pleistocene in Germany.[3] They underwent a reduction in range during glacial periods, and were confined to areas in Europe that were free of ice. During the mid-Pleistocene, Micromys minutus specimens also lived in parts of Asia.[4][5][6]. This suggests that they spread towards Asia when the ice sheets started to melt. Other evidence suggests that Micromys minutus could have been introduced accidentally through agricultural activities during Neolithic times.[7]

Before the harvest mouse had been formally described, Gilbert White believed they were an undescribed species, and reported their nests in Selborne, Hampshire:

They never enter into houses; are carried into ricks and barns with the sheaves; abound in harvest; and build their nests amidst the straws of the corn above the ground, and sometimes in thistles. They breed as many as eight at a litter, in a little round nest composed of the blades or grass or wheat. One of these nests I procured this autumn, most artificially platted,[8] and composed of the blades of wheat; perfectly round, and about the size of a cricket-ball. It was so compact and well-filled, that it would roll across the table without being discomposed, though it contained eight little mice that were naked and blind.[9]

Although the harvest mouse was first formally reported by Gilbert White, it was first reported in 1768 by Thomas Pennant.[10]

Conservation efforts have taken place in Britain since 2001. Tennis balls used in play at Wimbledon have been recycled to create artificial nests for harvest mice in an attempt to help the species avoid predation and recover from near-threatened status.[11]

Description

.jpg)

The harvest mouse ranges from 55 to 75 mm (2.2 to 3.0 in) long, and its tail from 50 to 75 mm (2.0 to 3.0 in) long; it weighs from 4 to 11 g (0.14 to 0.39 oz),[12][13] or about half the weight of the house mouse (Mus musculus). Its eyes and ears are relatively large. It has a small nose, with short, stubble-like whiskers, and thick, soft fur, somewhat thicker in winter than in summer.[14]

The upper part of the body is brown, sometimes with a yellow or red tinge; the under-parts range from white to cream coloured. It has a prehensile tail which is usually bicoloured and furless at the tip. The mouse's rather broad feet are adapted specifically for climbing, with a somewhat opposable, large outermost toe, allowing it to grip stems with each hindfoot and its tail,[14] thus freeing the mouse's forepaws for food collection. Its tail is also used for balance.

Ecology

Habitat and distribution

The harvest mouse is common in all east coast counties of England, reaching the North York Moors. It also inhabits less favourable habitats, such as woodlands and forests in the west.[7]

Harvest mice reside in a large variety of habitats, from hedgerows to railway banks. Harvest mice seem to have an affinity for all types of cereal heads, except for maize (Zea mays). Harvest mice typically like using monocotyledons for their nest-building, especially the common reed (Phragmites australis) and Siberian iris Iris sibirica.[7] Most harvest mice prefer wetlands for their nesting habitats.[15][16].

Harvest mice in Japan like making wintering nests near the ground from grasses that are dried, which indicates that they require vegetative cover in the winter, as well as in the warmer seasons.[17] Grasslands with a mix of perennials and annual grasses are required to balance the increases in nesting periods and the mice's need to secure nutrients.[18] Habitat selection might be the result of differences in the structure of the landscape of grasslands and wetlands in the area.[18]

Behaviour

Harvest mice are very skilled at climbing among grasses due to their short lactation period of 15-16 days.[19]. They spend most of their life in long grass and other vegetation such as reedbeds, rushes, ditches, cereals and legumes. They grasp leaves and stems with their feet and tail, which leaves their hands free for other tasks. These tasks can include grooming and feeding. Harvest mice have a prehensile tail that functions as an extra limb during climbing [20]. During the lactation period, the pups are able to climb a vertical bar by the time they first emerge from their nest. At 3-7 days they learn hand grasping, and at 6-9 days they learn food grasping. Between 6-11 days, they adopt a quadrupedal stance, and at 10-11 there is tail prehension, and righting at 10-12 days. The righting response in harvest mice develops earlier, but takes longer to master than the other skills the pups learn. They cannot climb horizontally by the time they are weaned, suggesting that horizontal climbing is not as essential as vertical climbing.[21]

Predators

Their predators include domesticated cats, barn owls, tawny owls, long-eared owls, little owls, and kestrels.[7]

Reproduction

In most rodent species, females prefer familiar males to unfamiliar ones.[22] The adaptive preference of mating with familiar males is not uncommon as familiarity is a proxy for quality that is seen in many solitary animals.[23]. Harvest mice are thought to be solitary, and the preference for familiar males over unfamiliar is a mechanism for inbreeding avoidance.[24] There is no size dimorphism between the sexes[25] so the females are considered dominant over the males. Females do not show interest in the male's odor. When females are in oestrus they spend more time with familiar males, and prefer the one that is heavier. While in dioestrus, the female spends more time with unfamiliar males. [26]

In most years in Britain, harvest mice build their first breeding nests in June or July; occasional nests are built earlier in April or early May. They prefer building their breeding nests above ground.[27] In Russia, harvest mouse breeding occurs in November and December in cereal ricks, buckwheat, and other cereal heads.[28]

Conservation

Due to their habitat, harvest mice are threatened by a number of anthropogenic effects such as farming, pesticide use, crop rotation, habitat destruction, fragmentation, and wetland draining.[18] Grasslands in Japan are rapidly decreasing in area, and are also becoming increasingly fragmented [18]. Urbanisation rate is another parameter for habitat destruction; in areas that are being urbanised more quickly, other species in the area will be forced into smaller areas. Spatial relationships between habitat patches are becoming increasingly important in these areas.[29]

Small salamanders require stagnant water in unsuitable habitats in more urban areas and since harvest mice have a similar ability to disperse, there is a risk that they may be forced to adapt to such environments when their preferred habitat is absent in the future.[18][30]

The first survey of the harvest mouse in Britain was conducted by the Mammal Society in the 1970s,[31]. and later followed up by the National Harvest Mouse survey in the late 1990s. These surveys indicated that harvest mouse nests were on a decline with 85% of the suitable habitat no longer available for the mice.[30]

Due to their declining population, the harvest mouse is currently protected under the UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework: Implementation Plan and the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981 [32][33].

References

- Kryštufek, B.; Lunde, D.P.; Meinig, H.; Aplin, K.; Batsaikhan, N.; Henttonen, H. (2019). "Micromys minutus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T13373A119151882. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T13373A119151882.en.

- Schiltter, Duane A.; Misonne, X. (31 August 1973). "African and Indo-Australian Muridae: Evolutionary Trend". Journal of Mammalogy. 54 (3): 795–796. doi:10.2307/1378990.

- Storch, G., Franzen, J. L. & Malec, F. (1973) Die altpleistozane Saugerfauna (Mammalia) von Hohensulzen bei Worms. Senckenbergiana lethaea, 54, 311-343.

- Zdansky, O. (1928) Die Saugetiere der Quartarfauna von Chou-K’ou-Tien. Palaeontologia sinica, series C, 5(4), 1-146.

- Yang, Z. (1934). On the Insectivora, Chiroptera, Rodentia and primates other than Sinanthropus from locality 1 at Choukoutien. Peiping (Peking): Geological survey of China.

- Pei, W. C. (1936) On the mammalian remains from locality 3 at Choukoutein. Palaeontologia sinica, series C, 7(5), 1-120.

- Harris, S. (1979). "History, distribution, status and habitat requirements of the harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) in Britain". Mammal Review. 9: 159–171. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1979.tb00253.x.

- "artificially platted": skillfully woven.

- White, The Natural History of Selborne, letter xii (4 November 1767).

- Pennant, T. (1768) British Zoology, 2, 498. B White, London. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.62499

- "'New balls, please' for mice homes". 25 June 2001 – via bbc.co.uk.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2004-11-19. Retrieved 2004-09-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Arkive: Micromys minutus". Archived from the original on 2010-08-29. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- Ivaldi, Francesca. "Micromys minutus". Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Rands, D.G. & Banks, C. (1973) The harvest mouse Micromys minutus in Bedfordshire: interim report. Bedfordshire Naturalist, 28, 35-41.

- Dillon, P. & Browne, M. (1975) Habitat selection and nest ecology of the harvest mouse Micromys minutus (Pallas). Wiltshire Natural History Magazine, 70, 3-9.

- Ishiwaka, R.; Yinoshita, Y.; et al. (July 2010). "Overwintering in nests on the ground in the harvest mouse". Landscape and Ecological Engineering. 6 (2): 335–342. doi:10.1007/s11355-010-0108-1.

- Sawabe, K.; Natahura, Y. (October 2016). "Extensive distribution models of the harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) in different landscapes". Global Ecology and Conservation. 8: 108–115. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2016.08.011.

- Ishiwaka, R. & Mori, T. 1998. Regurgitation feeding of young in harvest mice, Micromys minutus (Muridae, Rodentia). Journal of Mammalogy, 79, 1911–1917.

- Layne, J. N. 1959. Growth and development of the eastern harvest mouse, Reithrodontomys humulis. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum. Biological Science, 4, 59–82.

- Ishiwaka, R. & Mori, T. 1999. Early development of climbing skills in harvest mice, Micromys minutus (Muridae, Rodentia). Animal Behavior, 58, 203-209.

- Coopersmith, C. B.& Banks, E. M.1983. Effects of olfactory cues on sexual-behavior in the brown lemming, Lemmus trimucronatus. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 97,120-126.

- Randall, J. A., Hekkala, E. R., Cooper, L. D. & Barfield, J. 2002. Familiarity and flexible mating strategies of a solitary rodent, Dipodomys ingens. Animal Behaviour, 64, 11-21.

- Pusey, A. & Wolf, M. 1996. Inbreeding avoidance in animals. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 11, 201-206.

- Harris, S. & Trout, R. C. 1991. Harvest mouse Micromys minutus. In: The Handbook of British Mammals (Ed. by G. B. Corbet & S. Harris), pp. 233-239. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific.

- Brandt, R.; Macdonald, D.W. 2011. To know him is to love him? Familiarity and female preference in the harvest mouse, Micromys minutus. In: Animal Behaviour, 82(2):353-358.

- Harris, S. (1979), Breeding season, litter size and nestling mortality of the harvest mouse, Micromys minutus (Rodentia: Muridae), in Britain. Journal of Zoology, 188: 437-442. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1979.tb03427.x

- Sleptsov, M. M. (1948). [The breeding habitat of the Japanese Harvest mouse, Micromys minutus ussuricus Barr.-Ham.] Fauna Ekol. Gryzunov 2: 69-100.

- Fahrig, L. & Merriam, G. (1985), Habitat Patch Connectivity and Population Survival. Ecology, 66: 1762-1768. doi:10.2307/2937372

- Sargent, G. (1997), Harvest mouse in trouble. Mammal News, 111, 1.

- Flowerdew, J. R. (2004), Advances in the conservation of British mammals, 1954–2004: 50 years of progress with The Mammal Society. Mammal Review, 34: 169-210. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2004.00037.x

- JNCC and Defra (on behalf of the Four Countries’ Biodiversity Group). 2012. UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework. July 2012. Available from: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-6189.

- Legislation.gov.uk. (2017). Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. [online] Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/69/contents [Accessed 25 November 2019].