Equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in planetary orbit during different stages of the orbit. This planetary concept allowed Ptolemy to keep the theory of uniform circular motion alive by stating that the path of heavenly bodies was uniform around one point and circular around another point.

Placement

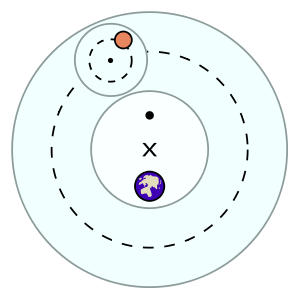

The equant point (shown in the diagram by the large • ), is placed so that it is directly opposite to Earth from the deferent's center, known as the eccentric (represented by the × ). A planet or the center of an epicycle (a smaller circle carrying the planet) was conceived to move at a constant angular speed with respect to the equant. In other words, to a hypothetical observer placed at the equant point, the epicycle's center (indicated by the small · ) would appear to move at a steady angular speed. However, the epicycle's center will not move at a constant speed along its deferent.[1]

The reason for the implementation of the equant was to maintain a semblance of constant circular motion of celestial bodies, a long-standing article of faith originated by Aristotle for philosophical reasons, while also allowing for the best match of the computations of the observed movements of the bodies, particularly in the size of the apparent retrograde motion of all Solar System bodies except the Sun and the Moon.

Equation

The angle α whose vertex is at the center of the deferent and whose sides intersect the planet and the equant respectively is a function of time t:

where Ω is the constant angular speed seen from the equant which is situated at a distance E when the radius of the deferent is R.[2]

The equant model has a body in motion on a circular path that does not share a center with Earth. The moving object's speed will actually vary during its orbit around the outer circle (dashed line), faster in the bottom half and slower in the top half. The motion is considered uniform only because the planet sweeps around equal angles in equal times from the equant point. The speed of the object is non-uniform when viewed from any other point within the orbit.

Discovery and use

Ptolemy introduced the equant in "Almagest". The evidence that the equant was a required adjustment to Aristotelian physics relied on observations made by himself and a certain "Theon" (perhaps, Theon of Smyrna).[1]

In models of the universe that precede Ptolemy, generally attributed to Hipparchus, the eccentric and epicycles were already a feature. The Roman Pliny in the 1st century CE, who apparently had access to writings of late Greek astronomers, and not being an astronomer himself, still correctly identified the lines of apsides for the five known planets and where they pointed in the zodiac.[3] Such data requires the concept of eccentric centers of motion. Most of what we know about Hipparchus comes to us through mentions of his works by Ptolemy in the Almagest. Hipparchus' models' features explained differences in the length of the seasons on Earth (known as the "first anomaly"), and the appearance of retrograde motion in the planets (known as the "second anomaly"). But Hipparchus was unable to make the predictions about the location and duration of retrograde motions of the planets match observations; he could match location, or he could match duration, but not both simultaneously.[4] Ptolemy's introduction of the equant resolved that contradiction: the location was determined by the deferent and epicycle, while the duration was determined by uniform motion around the equant.

Ptolemy's model of astronomy was used as a technical method that could answer questions regarding astrology and predicting planets positions for almost 1500 years, even though the equant and eccentric were violations of pure Aristotelian physics which required all motion to be centered on the Earth. For many centuries rectifying these violations was a preoccupation among scholars, culminating in the solutions of Ibn al-Shatir and Copernicus. Ptolemy's predictions, which required constant oversight and corrections by concerned scholars over those centuries, culminated in the observations of Tycho Brahe at Uraniborg.

It wasn't until Johannes Kepler published his Astronomia Nova, based on the data he and Tycho collected at Uraniborg, that Ptolemy's model of the heavens was entirely supplanted by a new geometrical model.[5][6]

Criticism

The equant solved the last major problem of accounting for the anomalistic motion of the planets but was believed by some to compromise the principles of the ancient Greek philosopher/astronomers, namely uniform circular motion about the Earth.[7] The uniformity was generally assumed to be observed from the center of the deferent, and since that happens at only one point, only non-uniform motion is observed from any other point. Ptolemy moved the observation point explicitly off the center of the deferent to the equant. This can be seen as breaking part of the uniform circular motion rules. Noted critics of the equant include the Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din Tusi who developed the Tusi-couple as an alternative explanation,[8] and Nicolaus Copernicus, whose alternative was a new pair of epicycles for each deferent. Dislike of the equant was a major motivation for Copernicus to construct his heliocentric system.[9][10] This violation of perfect circular motion around the center of the deferent bothered many thinkers, especially Copernicus who mentions the equant as a monstrous construction in De Revolutionibus. Copernicus' movement of the Earth away from the center of the universe obviated the primary need for Ptolemy's epicycles by explaining retrograde movement as an optical illusion, but he re-instituted two smaller epicycles into each planet's motion in order to replace the equant.

See also

- Equidimensional: This is a synonym for equant when it is used as an adjective.

References

- Evans, James (April 18, 1984). "On the function and probable origin of Ptolemy's equant" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 52 (12): 1080–89. Bibcode:1984AmJPh..52.1080E. doi:10.1119/1.13764. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- Eccentrics, deferents, epicycles and equants (Mathpages)

- Pliny the Elder. The Natural History, Book 2: An account of the world and the elements, Chapter 13: Why the same stars appear at some times more lofty and some times more near. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- "The New Astronomy - Equants, from Part 1 of Kepler's Astronomia Nova". science.larouchepac.com. Retrieved August 1, 2014. An excellent video on the effects of the equant

- Perryman, Michael (2012-09-17). "History of Astrometry". European Physical Journal H. 37 (5): 745–792. arXiv:1209.3563. Bibcode:2012EPJH...37..745P. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2012-30039-4.

- Bracco; Provost (2009). "Had the planet Mars not existed: Kepler's equant model and its physical consequences". European Journal of Physics. 30: 1085–92. arXiv:0906.0484. Bibcode:2009EJPh...30.1085B. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/30/5/015.

- Van Helden. "Ptolemaic System". Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Craig G. Fraser (2006). The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-313-33218-0.

- Kuhn, Thomas (1957). The Copernican Revolution. Harvard University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-674-17103-9. (copyright renewed 1985)

- Koestler A. (1959), The Sleepwalkers, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, p. 322; see also p. 206 and refs therein.

External links

- Ptolemaic System – at Rice University's Galileo Project

- Java simulation of the Ptolemaic System – at Paul Stoddard's Animated Virtual Planetarium, Northern Illinois University