Emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence[1] with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country).[2] Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanently move to a country).[3] Hence one might emigrate from one's native country to immigrate to another country. Both are acts of migration across national or other geographical boundaries.

Demographers examine push and pull factors for people to be pushed out of one place and attracted to another. There can be a desire to escape negative circumstances such as shortages of land or jobs, or unfair treatment. People can be pulled to the opportunities available elsewhere. Fleeing from oppressive conditions, being a refugee and seeking asylum to get refugee status in a foreign country, may lead to permanent emigration.

Forced displacement refers to groups that are forced to abandon their native country, such as by enforced population transfer or the threat of ethnic cleansing.

History

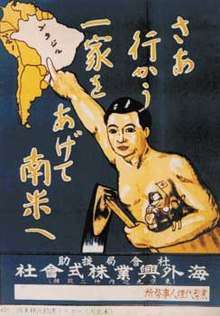

Patterns of emigration have been shaped by numerous economic, social, and political changes throughout the world in the last few hundred years. For instance, millions of individuals fled poverty, violence, and political turmoil in Europe to settle in the Americas and Oceania during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Likewise, millions left South China in the Chinese diaspora during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

"Push" and "pull" factors

Demographers distinguish factors at the origin that push people out, versus those at the destination that pull them in.[4] Motives to migrate can be either incentives attracting people away, known as pull factors, or circumstances encouraging a person to leave.

Push factors

- Lack of employment or entrepreneurial opportunities;

- Lack of educational opportunities;

- Lack of political or religious rights;

- Threat of arrest or punishment;

- Persecution or intolerance based on race, religion, gender or sexual orientation;

- Inability to find a spouse for marriage.

- Lack of freedom to choose religion, or to choose no religion;

- Shortage of farmland; hard to start new farms (historically);

- Oppressive legal or political conditions;

- Struggling or Failing economy;

- Military draft, warfare or terrorism;

- Famine or drought;

- Cultural fights with other cultural groups;

- Expulsion by armed force or coercion;

- Overpopulation.

Pull factors

- Favourable letters relatives or informants who have already moved; chain migration

- Better opportunities for acquiring farms for self and children

- Cheap purchase of farmland

- Quick wealth (as in a gold rush)

- More job opportunities

- Promise of higher pay

- Prepaid travel (as from relatives)

- Better welfare programmes

- Better schools

- Join relatives who have already moved; chain migration

- Building a new nation (historically)

- Building specific cultural or religious communities

- Political freedom

- Cultural opportunities

- Greater opportunity to find a spouse

- Favorable climate

- Easygoing to across the boundaries

Criticism

Some scholars criticize the "push-pull" approach to understanding international migration.[5] Regarding lists of positive or negative factors about a place, Jose C. Moya writes "one could easily compile similar lists for periods and places where no migration took place."[6]

Emigration waves by country

Search for "Emigration from" in titles

- Jews escaping from German-occupied Europe

- Yerida (Jewish emigration from Israel)

- Swedish emigration to the United States

Statistics

Unlike immigration, few if any records are maintained in regard to persons leaving a country either on a temporary or permanent basis. Therefore, estimates on emigration must be derived from secondary sources such as immigration records of the receiving country or records from other administrative agencies.[7]

The rate of emigration has continued to grow, reaching 280 million in 2017.[8]

Emigration restrictions

Some countries restrict the ability of their citizens to emigrate to other countries. After 1668, the Qing Emperor banned Han Chinese migration to Manchuria. In 1681, the emperor ordered construction of the Willow Palisade, a barrier beyond which the Chinese were prohibited from encroaching on Manchu and Mongol lands.[9]

The Soviet Socialist Republics of the later Soviet Union began such restrictions in 1918, with laws and borders tightening until even illegal emigration was nearly impossible by 1928.[10] To strengthen this, they set up internal passport controls and individual city Propiska ("place of residence") permits, along with internal freedom of movement restrictions often called the 101st kilometre, rules which greatly restricted mobility within even small areas.[11]

At the end of World War II in 1945, the Soviet Union occupied several Central European countries, together called the Eastern Bloc, with the majority of those living in the newly acquired areas aspiring to independence and wanted the Soviets to leave.[12] Before 1950, over 15 million people emigrated from the Soviet-occupied eastern European countries and immigrated into the west in the five years immediately following World War II.[13] By the early 1950s, the Soviet approach to controlling national movement was emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc.[14] Restrictions implemented in the Eastern Bloc stopped most East-West migration, with only 13.3 million migrations westward between 1950 and 1990.[15] However, hundreds of thousands of East Germans annually immigrated to West Germany through a "loophole" in the system that existed between East and West Berlin, where the four occupying World War II powers governed movement.[16] The emigration resulted in massive "brain drain" from East Germany to West Germany of younger educated professionals, such that nearly 20% of East Germany's population had migrated to West Germany by 1961.[17] In 1961, East Germany erected a barbed-wire barrier that would eventually be expanded through construction into the Berlin Wall, effectively closing the loophole.[18] In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, followed by German reunification and within two years the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

By the early 1950s, the Soviet approach to controlling international movement was also emulated by China, Mongolia, and North Korea.[14] North Korea still tightly restricts emigration, and maintains one of the strictest emigration bans in the world,[19] although some North Koreans still manage to illegally emigrate to China.[20] Other countries with tight emigration restrictions at one time or another included Angola, Egypt,[21] Ethiopia, Mozambique, Somalia, Afghanistan, Burma, Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia from 1975-1979), Laos, North Vietnam, Iraq, South Yemen and Cuba.[22]

See also

- Deportation

- Diaspora

- Eastern Bloc emigration and defection

- Émigré

- Exile

- Expatriate

- Feminization of migration

- Immigration

- Foot voting

- Human migration

- Settlement

- International Organization for Migration

- Migration Letters

- Political asylum

- Political migration

- Population transfer

- Refugee

- RMS Mooltan

- Separation barrier

- Snowbird (people), temporary seasonal tourists

References

- "emigrate". Miriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2017-08-18.

- "Emigration". Oxford Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- "Immigration". Oxford Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-05-18.

- Zeev Ben-Sira (1997). Immigration, Stress, and Readjustment. Greenwood. pp. 7–10. ISBN 9780275956325.

- Castles, Stephen, 1944- (2014). The age of migration : international population movements in the modern world. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 20–48. ISBN 9780230355767. OCLC 915478576.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Moya, J. C. (1998). Cousins and strangers. Spanish immigrants in Buenos Aires, 1850-1930. Berkeley, University of California Press. p.14

- Population andFamily Estimation Methods at Statistics Canada (PDF). Statistics Canada Demography Division. March 2012. ISBN 978-1-100-19900-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-23.

- "International Migration Report 2017" (PDF). United Nations. 2017. Retrieved 06/04/2019. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603-46.

- Dowty 1987, p. 69

- Dowty 1987, p. 70

- Thackeray 2004, p. 188

- Böcker 1998, p. 207

- Dowty 1987, p. 114

- Böcker 1998, p. 209

- Harrison 2003, p. 99

- Dowty 1987, p. 122

- Pearson 1998, p. 75

- Dowty 1987, p. 208

- Kleinschmidt, Harald, Migration, Regional Integration and Human Security: The Formation and Maintenance of Transnational Spaces, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006,ISBN 0-7546-4646-7, page 110

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos (2016). "Nasser's Educators and Agitators across al-Watan al-'Arabi: Tracing the Foreign Policy Importance of Egyptian Regional Migration, 1952-1967" (PDF). British Journal of Middle Eastern Countries. 43 (3): 324–341. doi:10.1080/13530194.2015.1102708. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- Dowty 1987, p. 186

External links

- Böcker, Anita (1998), Regulation of Migration: International Experiences, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 978-90-5589-095-8

- Dale, Gareth (2005), Popular Protest in East Germany, 1945-1989: Judgements on the Street, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7146-5408-9

- Dowty, Alan (1987), Closed Borders: The Contemporary Assault on Freedom of Movement, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-04498-0

- Harrison, Hope Millard (2003), Driving the Soviets Up the Wall: Soviet-East German Relations, 1953-1961, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-09678-0

- Krasnov, Vladislav (1985), Soviet Defectors: The KGB Wanted List, Hoover Press, ISBN 978-0-8179-8231-7

- Mynz, Rainer (1995), Where Did They All Come From? Typology and Geography of European Mass Migration In the Twentieth Century; European Population Conference Congress European De Demographie, United Nations Population Division

- Pearson, Raymond (1998), The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-312-17407-1

- Thackeray, Frank W. (2004), Events that changed Germany, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-32814-5

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos (2015), "Why Do States Develop Multi-tier Emigrant Policies? Evidence from Egypt" (PDF), Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41 (13): 2192–2214, doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1049940, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016, retrieved 4 December 2016

External links

| Look up emigration in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Translation from Galician to English of 4 Classic Emigration Ballads