Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester

Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester (née Cobham; c.1400 – 7 July 1452), was a mistress and the second wife of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. A convicted sorceress, her imprisonment for treasonable necromancy in 1441 was a cause célèbre.[1]

| Eleanor Cobham | |

|---|---|

| Duchess of Gloucester | |

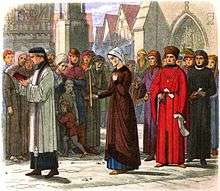

Eleanor and her husband Humphrey | |

| Born | c. 1400 Sterborough Castle, Kent |

| Died | 7 July 1452 (aged c. 52).[1] Beaumaris Castle, Anglesey.[1] |

| Spouse | Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (m. bet. 1428–1431; ann. c. 1441) |

| Father | Reynold Cobham, 3rd Baron Cobham |

| Mother | Eleanor Culpeper |

Family

Eleanor was daughter of Reginald Cobham, 3rd Baron Sterborough,[2] 3rd Lord Cobham, and his first wife, Eleanor Culpeper (d. 1422), daughter of Sir Thomas Culpeper, of Rayal.[1]

Mistress and wife to the Duke of Gloucester

In about 1422 Eleanor became a lady-in-waiting to Jacqueline d'Hainault, who, on divorcing John IV, Duke of Brabant, had fled to England in 1421. In 1423, Jacqueline married Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the youngest son of King Henry IV, [1] who since the death of his elder brother King Henry V was Lord Protector of the child king Henry VI and a leading member of his council.

Gloucester went to France to wrest control of his wife's estates in Hainault. On his return to England in 1425 Eleanor became his mistress. In January 1428, the Duke's marriage to Jacqueline was annulled and he married Eleanor.[1] According to Harrison, "Eleanor was beautiful, intelligent, and ambitious and Humphrey was cultivated, pleasure-loving, and famous".[1] Over the next few years they were the centre of a small but flamboyant court based at La Plesaunce in Greenwich, surrounded by poets, musicians, scholars, physicians, friends and acolytes.[1] In November 1435, Gloucester placed his whole estate in a jointure with Eleanor and six months later, in April 1436, she was granted the robes of a duchess for the Garter ceremony.[1]

In 1435, Gloucester's elder brother, John, Duke of Bedford died, making Humphrey heir presumptive to the English throne. Gloucester also claimed the role of regent, hitherto occupied by his brother, but was opposed in that endeavour by the council. [1] His wife Eleanor had some influence at court and seems to have been liked by Henry VI.

Trial and imprisonment

Eleanor consulted astrologers to try to divine the future. The astrologers Thomas Southwell and Roger Bolingbroke predicted that Henry VI would suffer a life-threatening illness in July or August 1441.[1] When rumours of the prediction reached the king's guardians, they also consulted astrologers who could find no such future illness in their astrological predictions, a comfort for the king, who had been troubled by the rumours. They also followed the rumours to their source and interrogated Southwell, Bolingbroke and John Home (Eleanor's personal confessor), then arrested Southwell and Bolingbroke on charges of treasonable necromancy. Bolingbroke named Eleanor as the instigator but she had fled to sanctuary in Westminster Abbey so could not be tried by the law courts.[3] The charges against her were possibly exaggerated to curb the ambitions of her husband.

Eleanor was examined by a panel of religious men whilst in sanctuary and she denied most of the charges but confessed to obtaining potions from Margery Jourdemayne, "the Witch of Eye". Her explanation was that they were potions to help her conceive. [3] Eleanor and her fellow conspirators were found guilty. Southwell died in the Tower of London, Bolingbroke was hanged, drawn and quartered, and Jourdemayne was burnt at the stake. Eleanor had to do public penance in London, divorce her husband and was condemned to life imprisonment.[1] In 1442, Eleanor was imprisoned at Chester Castle,[4] then in 1443 moved to Kenilworth Castle. This move may have been prompted by fears that Eleanor was gaining sympathy amongst the Commons, for just a few months prior an unnamed Kentish woman had met with Henry VI at Black Heath and scolded him for his treatment of Eleanor, saying he should bring her home to her husband. [3] The woman was punished by execution. In July 1446 Eleanor was moved to the Isle of Man, and finally in March 1449 to Beaumaris Castle in Anglesey, where she died on 7 July 1452.[1]

Children

Eleanor's husband Humphrey had two known children, Arthur and Antigone. Sources are divided about whether they were born to Eleanor before the marriage, or were the offspring of an "unknown mistress or mistresses".[5] K.H. Vickers, Alison Weir and Cathy Hartley all suggest that Eleanor was their mother, though other authors treat their maternity as unknown.[6] Antigone, however, had her first child in November 1436 suggesting she was born at the very latest in 1424 which may suggest that she was born before Eleanor became involved with Humphrey[7]. Thus, Eleanor's children may have been:

- Arthur Plantagenet (d. 1447),[8]

- Antigone Plantagenet, who married Henry Grey, 2nd Earl of Tankerville, Lord of Powys (c. 1419–1450) and then John d'Amancier.[9]

Notes

- Harris 2008.

- Both The Complete Peerage and Harris in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography state Sterborough was then in Surrey (Harris 2008)

- Hollman, Gemma. Royal Witches: From Joan of Navarre to Elizabeth Woodville. History Press, 2019.

- Lewis, Thacker & she was 2003, pp. 55–58.

- Richardson 2005, pp. 492, 493. Richardson's many sources and research are outlined within the entries in his book.

- K.H. Vickers – Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester: A Biography. 1907; Alison Weir, Britain's Royal Family: A Complete Genealogy (London, U.K.: The Bodley Head, 1999), page 125; Hartley, Cathy – A Historical Dictionary of British Women – First published as The Europa Biographical Dictionary of British Women, 1993 (Rev, 2003)

- Rundle, David (2014). "Good Duke Humfrey: bounder, cad and bibliophile". Bodleian Library Record. xxvii (1): 40.

- Weir 1999, p. .

- Fresne, p. 331.

References

- Fresne, Gaston Louis Emmanuel du, Marquis de Beaucourt (1881–1891). Histoire de Charles VII (6 vols). 5. Paris. p. 331.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, G. L. (January 2008). "Eleanor , duchess of Gloucester (c.1400–1452)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5742.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hollman, Gemma (2019). Royal Witches: From Joan of Navarre to Elizabeth Woodville. Cheltenham: The History Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, C.P.; Thacker, A.T., eds. (2003). "The City of Chester: General History and Topography". Later medieval Chester 1230-1550: City and crown, 1350-1550', A History of the County of Chester. 5, part 1. pp. 55–58. Retrieved 3 February 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richardson, Douglas (2005). Magna Carta ancestry. Genealogical Publishing. pp. 492, 493.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weir, Alison (1999). Britain's Royal Family: A Complete Genealogy. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-09-953973-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)