Early history of the IRT subway

The first regularly operated subway in New York City was built by the city, and upon the completion of the subway's first segment in 1904, it was leased to the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) for operation under Contracts 1 and 2, along with contract 3 of the Dual Contracts. For fourteen years, it consisted of a single trunk line below 96th Street with several northern branches. In 1918, a new "H" system was placed in service, with separate East Side and West Side lines; these lines still operate as part of the New York City Subway.

The system had four tracks between Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall and 96th Street, allowing for local and express service on that portion. Under the "H" system, the original line and early extensions were rearranged as follows:

- The IRT Eastern Parkway Line from Atlantic Avenue–Barclays Center to Borough Hall

- The IRT Lexington Avenue Line from Borough Hall to Grand Central–42nd Street

- The IRT 42nd Street Shuttle from Grand Central–42nd Street to Times Square

- The IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line from Times Square to Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street

- The IRT Lenox Avenue Line from 96th Street to 145th Street

- The IRT White Plains Road Line from 142nd Street Junction to 180th Street–Bronx Park (removed north of 179th Street)

History

Planning

Planning for the system that was built began with the Rapid Transit Act, signed into law on May 22, 1894, which created the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. The act provided that the commission would lay out routes with the consent of property owners and local authorities, either build the system or sell a franchise for its construction, and lease it to a private operating company.[1]:139–161 The subway plans were drawn up by a team of engineers led by William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer of the Rapid Transit Commission. It called for a subway line from New York City Hall in lower Manhattan to the Upper West Side, where two branches would lead north into the Bronx.[2]:3 As part of the project, Parsons investigated other cities' transit systems to determine features that could be used in the new subway.[3]

A line through Lafayette Street (then Elm Street) to Union Square was considered, but at first, a more costly route under lower Broadway was adopted. A legal battle with property owners along the route led to the courts denying permission to build through Broadway in 1896. The Elm Street route was chosen later that year, cutting west to Broadway via 42nd Street. This new plan, formally adopted on January 14, 1897, consisted of a line from City Hall north to Kingsbridge and a branch under Lenox Avenue and to Bronx Park, to have four tracks from City Hall to the junction at 103rd Street. The "awkward alignment...along Forty-Second Street", as the commission put it, was necessitated by objections to using Broadway south of 34th Street. Legal challenges were finally taken care of near the end of 1899.[1]:139–161 Elm Street was widened and cut through from Centre Street and Duane Street to Lafayette Place to provide a continuous thoroughfare for the subway to run under.[4]:227

A contract, later known as Contract 1, was executed on February 21, 1900, between the commission and the Rapid Transit Construction Company, organized by John B. McDonald and funded by August Belmont Jr., for the construction of the subway and a 50-year operating lease from the opening of the line. Ground was broken at City Hall on March 24.[1]:162–191

On February 26, the Board instructed the Chief Engineer to evaluate the feasibility of extending the subway south to South Ferry, and then to Brooklyn. To ensure that the RTC was legally permitted to construct the subway into areas of the city that were added as part of Consolidation in 1898, which occurred after the Act of 1894 was passed, a bill was passed and became law on April 23, 1900. In May 1900, two routes were examined for the Brooklyn extension. One route would have run under Broadway to Whitehall Street, under the East River, Joralemon Street, Fulton Street, and Flatbush Avenue to Atlantic Avenue. The second route would have followed the first route but would have gone to Hamilton Avenue before going towards Bay Ridge and South Brooklyn. On January 24, 1901, the Board adopted the first route, which would extend the subway from City Hall to the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)'s Flatbush Avenue terminal station (now known as Atlantic Terminal) in Brooklyn. The line's cost was expected to be no greater than $8 million.[4]:83–84 Contract 2, giving a lease of only 35 years, was executed between the commission and the Rapid Transit Construction Company on September 11, with construction beginning at State Street in Manhattan on November 8, 1902. Belmont incorporated the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) in April 1902 as the operating company for both contracts; the IRT leased the Manhattan Railway, operator of the four elevated railway lines in Manhattan and the Bronx, on April 1, 1903.[1]:162–191

Construction

On July 12, 1900, the contract was modified to widen the subway at Spring Street to allow for the construction of 600 feet (183 m) of a fifth track, and to lengthen express station platforms to 350 feet (107 m) to accommodate longer trains.[4]:82, 249 On June 21, 1900, the route of Contract 1 was modified at Fort George in Upper Manhattan. The route was changed to run over Nagle Avenue and Amsterdam Avenue instead of over Ellwood Street, between Eleventh Avenue and Kingsbridge Avenue or Broadway. The route of the terminal loop at City Hall was shortened to only be constructed between City Hall and the Post Office instead of passing completely around the Post Office as a result of a change issued on January 10, 1901.[5]:189–190 In addition, the loop was changed from being double-tracked to single tracked. The loop was designed to allow local trains to be turned around, and to pass under the express tracks under Park Row without an at-grade crossing, and to allow for a possible future extension south under Broadway. To allow for the switching back of express trains, a relay track was constructed under Park Row, allowing for a future southern extension under Broadway.[4]:226, 249 The line south of Dyckman Street would be built underground, except for the section surrounding 125th Street, which would run across the elevated Manhattan Valley Viaduct to cross a deep valley there.[6]

On December 20, 1900, the contractor requested that the plans for the Manhattan Valley Viaduct be modified to allow for a three-track structure and for the construction of a third track at the 145th Street, 116th Street, and 110th Street stations. The Board adopted the request on January 24, 1901. Some time after, the contractor requested permission to construct a third track for storage. The Board authorized the construction of a third track from 103rd Street to 116th Street on March 7, 1901. The contractor petitioned the board once more for the permission to build a third track continuously from 137th Street to 103rd Street, some of which was already authorized, and to build a storage yard between 137th Street and 145th Street, with three tracks on either side of the main line to allow for the storage of 150 cars. The Board authorized the request on May 2, 1901 and rescinded the March 7 resolution. The new resolution specified that the third track would be for express trains.[4]:93[5]:189–190 However, construction on the section between 104th Street and 125th Street had already begun prior to the design change, requiring that a portion of the work be undone.[4]:240–241 As part of the modifications for a third track, a third track was added to both the upper and lower levels of the subway directly north of 96th Street, immediately to the east of the originally planned two tracks.[7]:14

In 1902, the contractor requested permissIon to build an additional third track from Fort George to Kingsbridge. The Board authorized the construction of the track on January 15, 1903,[8]:35 and it was formally approved on March 24, 1904.[5]:191

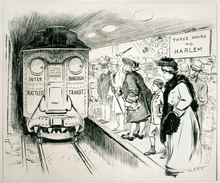

The Contractor for the subway purchased a large area of land on the Harlem River near 150th Street for the construction of a terminal for the East Side Line. On October 24, 1901, the Board voted to extend the line from 143rd Street to the terminal. As part of the plan, a station would be built at 145th Street instead of at 141st Street and Lenox Avenue.[9]:781 Some trains would originate at 145th Street instead of Bronx Park. This change was expected to promote the benefits of using the subway for travel to Harlem.[4]:94 On April 28, 1902, Mayor Low signed the ordinance providing for the extension.[10] On January 16, 1903, a modification to Contract 1 was made to allow for the extension of the Lenox Avenue Line from 142nd Street to 148th Street with a stop between 142nd Street and Exterior Street. The stop was placed at 145th Street along tracks that were only intended to lead to Lenox Yard.[11][12]:387–415

Also in 1903, residents in the vicinity of 104th Street and Central Park West urged the board to build a station at this location. They cited the long distance between the two nearest subway stations, and the need to serve Central Park West. The Board declined to construct the station after serious consideration. They found that the station's construction would have delayed the opening of the line, and would have slowed service for passengers using the Lenox Avenue Line coming from the Bronx.[8]:43 Residents of the area requested the construction of a station at this location again in 1921.[13]

The soil excavated during construction went to various places.[14] In particular, Ellis Island in New York Harbor was expanded from 2.74 acres (1.11 ha) to 27.5 acres (11.1 ha), partially with soil from the excavation of the IRT line,[15] while nearby Governors Island was expanded from 69 acres (28 ha) to 172 acres (70 ha).[16] The excavated Manhattan schist was also used to construct buildings for the City College of New York.[14]

Opening

Operation of the subway began on October 27, 1904,[17] with the opening of all stations from City Hall to 145th Street on the West Side Branch.[1]:162–191[5]:189 The car fleet available includes the first production all-steel passenger cars in the world from an order of 300 placed with American Car and Foundry.[18]:27 Service was extended to 157th Street, before it fully opened on November 12, 1904 for a football game, but officially opened on December 4.[5]:191 On November 23, 1904, the East Side Branch, or Lenox Avenue Line, opened to 145th Street.[5]:191 The West Side Branch was extended northward to a temporary terminus of 221st Street and Broadway on March 12, 1906.[5]:191[19] This extension was served by shuttle trains operating between 157th Street and 221st Street.[20] On April 14, 1906, the shuttle trains started stopping at 168th Street. On May 30, 1906, the 181st Street station opened, and the shuttle operation ended.[21]:71, 73 Through service began north of 157th Street, with express trains terminating at 168th Street or 221st Street.[21]:175–176 The 207th Street station was completed, but did not open until April 1, 1907 because the bridge over the Harlem River was not yet completed.[22]

Beginning on June 18, 1906, all Lenox Avenue Expresses began running to the West Farms Line. Previously, some of the expresses ran to the 145th Street station.[21]:78

The original system as included in Contract 1 was completed on January 14, 1907, when trains started running across the Harlem Ship Canal on the Broadway Bridge to 225th Street,[19] meaning that 221st Street could be closed.[5]:191 Once the line was extended to 225th Street, the structure of the 221st Street was dismantled and was moved to 230th Street for a new temporary terminus. Service was extended to the temporary terminus at 230th Street on January 27, 1907.[5]:191 An extension of Contract 1, officially Route 14, north to 242nd Street at Van Cortlandt Park was approved on November 1, 1906.[1]:204 This change also called for the abandonment of the route along 230th Street.[5]:191 This extension opened on August 1, 1908.[5]:191[23] (The original plan had been to turn east on 230th Street to just west of Bailey Avenue, at the New York Central Railroad's Kings Bridge station.[24]) When the line was extended to 242nd Street the temporary platforms at 230th Street were dismantled, and were rumored to be brought to 242 Street to serve as the station's side platforms. There were two stations on the line that opened later; 191st Street and 207th Street. The 191st Street station did not open until January 14, 1911 because the elevators and other work had not yet been completed.[22]

Extensions and modifications

The initial segment of the IRT White Plains Road Line opened on November 26, 1904 between East 180th Street and Jackson Avenue. Initially, trains on the line were served by elevated trains from the IRT Second Avenue Line and the IRT Third Avenue Line, with a connection running from the Third Avenue local tracks at Third Avenue and 149th Street to Westchester Avenue and Eagle Avenue. Once the connection to the IRT Lenox Avenue Line opened on July 10, 1905, trains from the newly opened IRT subway ran via the line.[25] Elevated service via this connection was resumed on October 1, 1907 when Second Avenue locals were extended to Freeman Street during rush hours.[26]

The line was then extended to Fulton Street on January 16, 1905,[27] to Wall Street on June 12, 1905,[22] and to Bowling Green and South Ferry on July 10, 1905.[28] In order to complete Contract 2, the subway had to be extended under the East River to reach Brooklyn. The tunnel was named the Joralemon Street Tunnel, which was the first underwater subway tunnel connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn, and it opened on January 9, 1908, extending the subway from Bowling Green to Borough Hall.[29] On May 1, 1908, the construction of Contract 2 was completed when the line was extended from Borough Hall to Atlantic Avenue near the Flatbush Avenue LIRR station.[30] With the opening of the IRT to Brooklyn, ridership fell off on the BRT's elevated and trolley lines over the Brooklyn Bridge as Brooklyn riders chose to use the new subway.[31]

On June 18, 1908, a modification to Contract 2 was made to add shuttle service between Bowling Green and South Ferry. At the time, of the trains that continued south of City Hall, some trains ran through to Brooklyn, with the rest running to South Ferry before returning to uptown service. It was determined that the operation of trains via the South Ferry Loop impeded service to Brooklyn, prohibiting a doubling of Brooklyn service. In order to increase Brooklyn service, it was decided to continue serving South Ferry via shuttle service. An additional island platform and track were constructed on the west side of the Bowling Green station to allow for the shuttle's operation. The cost was estimated to be $100,000. While the change inconvenienced South Ferry riders, it stood to benefit the greater number of Brooklyn riders.[32]

On June 27, 1907, a modification–the 96th Street Improvement–was made to Contract 1 to add additional tracks at 96th Street in order to remove the at-grade junction north of the 96th Street station. Here, trains from Lenox Avenue and Broadway would switch to get to the express or local tracks and would delay service. One additional track would have run from 96th Street along the east side of Broadway, branching off the northbound local track and running parallel before merging back into that track at 102nd Street. At 100th Street, a spur would connect to the other tracks. Two additional tracks would have been constructed, running along the west side of Broadway from 96th Street to 101st Street. The first of these two tracks would have branched off of the southbound local track and run parallel before merging back into that track at 101st Street. The second of these two tracks would have diverged from the first additional track on the west side of Broadway, and would run parallel and at the same grade until 98th Street. Here, the track would descend to the level of the center or Lenox Avenue Line tracks. At 101st Street the track would curve and connect with the southbound track of the Lenox Avenue Line.[33] The tracks would have been constructed with the necessary fly-under tracks and switches.[7]:14

The work was partially completed in 1908, but was stopped because the introduction of speed-control signals made the remainder of the project unnecessary. Provisions were left to allow the work to be completed later on. The signals were put into place at 96th Street on April 23, 1909. The new signals allowed trains approaching a station to run more closely to the stopped train, eliminating the need to be separated by hundreds of feet. The new signals were also installed at Grand Central, 14th Street, Brooklyn Bridge, and 72nd Street.[5]:85–87, 191

On August 9, 1909, a modification to Contract 1 was made, allowing for the construction of an infill station on the West Farms Branch at Intervale Avenue. Construction of the station began in December 1909. The station opened on April 30, 1910 even though work on the station was not completed until July. In February 1910, work began on the construction of a permanent terminal for the West Farms Branch at Zoological Park at 181st Street and Boston Road, replacing the temporary station at this location. The new station cost $30,000[5]:10 and opened on October 28, 1910.[34]:105–106

On January 18, 1910, a modification was made to Contracts 1 and 2 to lengthen station platforms to increase the length of express trains to eight cars from six cars, and to lengthen local trains from five cars to six cars. In addition to $1.5 million spent on platform lengthening, $500,000 was spent on building additional entrances and exits. It was anticipated that these improvements would increase capacity by 25 percent.[34]:15

On January 23, 1911 ten-car express trains began running on the Lenox Avenue Line, and on the following day, ten-car express trains were inaugurated on the Broadway Line. The platforms at all but three express stations were extended to accommodate ten-car trains. The platforms at 168th Street and 181st Street, and the northbound platform at Grand Central, were not extended. Until the platform extensions were completed the first two-cars of trains did not platform. All southbound stations on the Broadway Line north of 96th Street and on the White Plains Road Line north of 149th Street, as well as at Mott Avenue, Hoyt Street, and Nevins Street, were only eight cars long.[35]

Service pattern

Express trains began at South Ferry in Manhattan or Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, while local trains typically began at South Ferry or City Hall, both in Manhattan. Local trains to the West Side Branch (242nd Street) ran from City Hall during rush hours and continued south at other times; East side local trains ran between City Hall and 145th Street. All three branches were served by express trains; no local trains used the East Side Branch to West Farms (180th Street).[36] Express trains to 145th Street were later eliminated; all West Farms express trains and rush hours Broadway express trains operated through to Brooklyn.[37] Essentially each branch had a local and an express, with express service to Broadway (242nd Street) and West Farms and local service to Broadway and Lenox Avenue (145th Street).[38]

When the "H" system opened in 1918, all trains from the old system were sent south from Times Square–42nd Street along the new IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line. Local trains (Broadway and Lenox Avenue) were sent to South Ferry, while express trains (Broadway and West Farms) used the new Clark Street Tunnel to Brooklyn.[39] These services became 1 (Broadway express and local), 2 (West Farms express), and 3 (Lenox Avenue local) in 1948. The only major change to these patterns was made in 1959, when all 1 trains became local and all 2 and 3 trains became express.[40][41][42] The portion south of Grand Central–42nd Street became part of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line, and now carries 4 (express), 5 (express), 6 (local), and <6> (local) trains; the short piece under 42nd Street is now the 42nd Street Shuttle.[39]

Station design

The designs of the underground stations generally conformed to a similar format. With few exceptions, there were two types of stations that chief architect William Barclay Parsons's team designed as part of Contract 1. Local stations, which served only local trains, had side platforms located on the outside of the tracks, while express stations served both local and express trains and had island platforms between each direction's pair of local and express tracks. Generally, express platforms as well as local platforms north of 96th Street were originally 350 feet (110 m) long, though the local platforms south of 96th Street were shorter, at 200 feet (61 m). The sole exception was the City Hall station, which was designed to a much more ornate style than all of the other stations and consisted of one looping track.[2]:4

The designs of the stations were inspired by those of the Paris Métro,[2]:5 whose design Parsons was impressed by.[3]:46–47 Heins & LaFarge were commissioned to design the stations' decorations, as well as the entrance and exit kiosks and buildings.[2]:3 Most of the stations were located just below ground level and had a fare control (turnstile) area at the same level as the platform, though several stations also had mezzanines over the platforms. The roofs of the platforms were supported by cast iron columns placed every 15 feet (4.6 m). Additional columns between the tracks, placed every 5 feet (1.5 m), supported the jack-arched concrete station roofs. Each platform consisted of 3-inch-thick (7.6 cm) concrete slabs, beneath which were located drainage basins.[2]:4 The City Hall station was distinctive in that it instead contained vaulted ceilings with Guastavino tile.[2]:6

The station walls were made to slightly different designs in each station. The lowermost portion of the walls were either Roman brick or marble, above which was wainscoting; the rest of the walls were then made of white glass or glazed tile. At the top of each station wall was a frieze, interspersed with plaques signifying the street name or number, as well as plaques with a symbol that is associated with a local landmark or something else of local significance.[2]:5 Heins & LaFarge worked with the ceramic-producing firms Grueby Faience Company of Boston and Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati to create the ceramic plaques.[43][44] In addition, mosaic tablets with the name of the station were put at regular intervals within the station wall.[2]:5

Stations

| Station | Tracks | Opened | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Branch | |||

| Atlantic Avenue | 2 | May 1, 1908[30] | |

| Nevins Street | 2 | May 1, 1908[30] | |

| Hoyt Street | 2 | May 1, 1908[30] | |

| Borough Hall | 2 | January 9, 1908[28][29] | |

| South Ferry | 2 (loops) | July 10, 1905[28] | Closed February 13, 1977 |

| Bowling Green | 2 | July 10, 1905[28] | |

| Wall Street | 2 | June 12, 1905[45] | |

| Fulton Street | 2 | January 16, 1905[46] | |

| City Hall | 1 (loop) | October 27, 1904[47] | Closed December 31, 1945[48] |

| Brooklyn Bridge | all | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| Worth Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | Closed September 1, 1962[49] |

| Canal Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| Spring Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| Bleecker Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| Astor Place | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 14th Street–Union Square | all | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 18th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | Closed November 8, 1948[50] |

| 23rd Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 28th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 33rd Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| Grand Central–42nd Street | all | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| Times Square | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 50th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 59th Street–Columbus Circle | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 66th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 72nd Street | all | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 79th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 86th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 91st Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | Closed February 2, 1959[51] |

| 96th Street | all | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| West Side Branch (splits at 96th Street) | |||

| 103rd Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 110th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 116th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| Manhattan Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 137th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 145th Street | local | October 27, 1904[47] | |

| 157th Street | November 12, 1904[52] | ||

| 168th Street | April 14, 1906[53] | ||

| 181st Street | May 30, 1906[54][22] | ||

| 191st Street | January 14, 1911[55] | ||

| Dyckman Street | March 12, 1906[56] | ||

| 207th Street | local | April 1, 1907[22] | |

| 215th Street | local | March 12, 1906[56] | |

| 221st Street | local | March 12, 1906[56] | Closed January 14, 1907[22] |

| 225th Street | local | January 14, 1907[19] | |

| 231st Street | local | January 27, 1907[22] | |

| 238th Street | local | August 1, 1908[57] | |

| Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street | August 1, 1908[57] | ||

| West Side Branch to Lenox Avenue (splits at 96th Street) | |||

| 110th Street | all | November 23, 1904[58] | |

| 116th Street | all | November 23, 1904[58] | |

| 125th Street | all | November 23, 1904[58] | |

| 135th Street | all | November 23, 1904[58] | |

| 145th Street | all | November 23, 1904[58] | |

| West Side Branch to West Farms (splits from branch to Lenox Avenue at 142nd Street Junction) | |||

| Mott Avenue | all | July 10, 1905[28] | |

| 149th Street | all | July 10, 1905[28] | Free transfer to Third Avenue Elevated in same direction |

| Jackson Avenue | local | November 26, 1904[28] | |

| Prospect Avenue | local | November 26, 1904[28] | |

| Intervale Avenue | local | April 30, 1910[34] | |

| Simpson Street | local | November 26, 1904[28] | |

| Freeman Street | local | November 26, 1904[28] | |

| 174th Street | local | November 26, 1904[28] | |

| 177th Street | local | November 26, 1904[28] | |

| 180th Street | November 26, 1904[28] | The only part of the original subway to be completely demolished | |

See also

References

- Walker, James Blaine (1918). Fifty Years of Rapid Transit — 1864 to 1917. New York, N.Y.: Law Printing. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "IRT Subway System Underground Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 23, 1979. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- Parsons, W.B. (1894). Report to the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners: In and for the City of New York on Rapid Transit in Foreign Cities.

- Report of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners For And In The City of New York Up to December 31, 1901. Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. 1902.

- Report of the Public Service Commission For The First District of the State of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1909. Albany: Public Service Commission. 1910.

- "Interborough Rapid Transit System, Manhattan Valley Viaduct" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 24, 1981. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "New York City's Subway Turns 100" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 47 (10). October 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 3, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- Report of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners For And In The City of New York Up to December 31, 1903. Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. 1904.

- Proceedings of the Public Service Commission for the First District State of New York From July 1 to December 31st, 1907. New York Public Service Commission, First District. 1907.

- "RAPID TRANSIT EXTENSION.; Mayor Signs Ordinance for Lenox Avenue Line to 150th Street". The New York Times. April 29, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- Minutes of the Board of Estimate and Apportionment of the City of New York, Financial and Franchise Matters. Board of Estimate and Apportionment. 1910. p. 3705.

- Contract for construction and operation of rapid transit railroad (Manhattan and the Bronx) With supplemental agreements to November 24th, 1903. Contract dated February 21st, 1900. Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. 1903.

- "SEEK NEW SUBWAY STATION; Commission Hears Pleas for 104th St. Entrance--Reserves Decision". The New York Times. March 3, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- Saraniero, Nicole (August 16, 2018). "Where Did the Rubble Go?: 6 Spots Built from NYC's Subway Excavation". Untapped Cities. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- "Fact Sheet: Statue of Liberty NM -- Ellis Island". National Parks of New York Harbor (U.S. National Park Service). May 11, 1965. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- Chan, Sewell (August 10, 2016). "An Elusive Island of Good Intentions". City Room. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- "EXERCISES IN CITY HALL.; Mayor Declares Subway Open -- Ovations for Parsons and McDonald". The New York Times. October 28, 1904. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Cudahy, Brian J. (2003). A Century of Subways: Celebrating 100 Years of New York's Underground Railways. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-2292-6.

- "Farthest North in Town by the Interborough — Take a Trip to the New Station, 225th Street West — It's Quite Lke the Country — You Might Be in Dutchess County, but You Are Still In Manhattan Borough — Place Will Bustle Soon". The New York Times. January 14, 1907. p. 18. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- Media:1906 IRT map north.png

- Report of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners for and in the City of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1906. 1907.

- Merritt, A. L. (1914). "Ten Years of the Subway (1914)". www.nycsubway.org. Interborough Bulletin. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- "Our First Subway Completed At Last — Opening of the Van Cortlandt Extension Finishes System Begun in 1900 — The Job Cost $60,000,000 — A Twenty-Mile Ride from Brooklyn to 242d Street for a Nickel Is Possible Now". The New York Times. August 2, 1908. p. 10. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- Burroughs and Company, the New York City Subway Souvenir, 1904.

- "Discuss Subway Signs in 18th St. Station — Engineer Parsons and Mr. Hedley Inspect Advertising Scheme — Bronx Viaduct Works Well — Delays There Only Those of Newness — Lenox Avenue Service Makes Fuss Below Ninety-Sixth Street". The New York Times. November 27, 1904. p. 3. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- Kahn, Alan Paul; May, Jack (1973). Tracks of New York Number 3 Manhattan and Bronx Elevated Railroads 1920. New York City: Electric Railroaders' Association. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Subway at Fulton Street Busy". The New York Times. January 17, 1905. p. 9. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Subway Trains Running From Bronx to Battery — West Farms and South Ferry Stations Open at Midnight — Start Without a Hitch — Bowling Green Station Also Opened — Lenox Avenue Locals Take City Hall Loop Hereafter". The New York Times. July 10, 1905. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Subway to Brooklyn Opened for Traffic — First Regular Passenger Train Went Under the East River Early This Morning — Not a Hitch in the Service — Gov. Hughes and Brooklyn Officials to Join in a Formal Celebration of Event To-day". The New York Times. January 9, 1908. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Brooklyn Joyful Over New Subway — Celebrates Opening of Extension with Big Parade and a Flow of Oratory — An Ode to August Belmont — Anonymous Poet Calls Him "the Brownie of the Caisson and Spade" — He Talks on Subways". The New York Times. May 2, 1908. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Another Centennial–Original Subway Extended To Fulton Street". New York Division Bulletin. New York Division, Electric Railroaders' Association. 48 (1). January 2005. Retrieved August 31, 2016 – via Issu.

- Minutes of the Board of Estimate and Apportionment of the City of New York Financial and Franchise Matters From April 1 to June 30, 1908. Board of Estimate and Apportionment. 1908. pp. 2292–2296.

- Agreement Modifying Contract For Construction And Operation Of Rapid Transit Railroad Additional Tracks Near 96th Street. Rapid Transit Board. June 27, 1907.

- Report of the Public Service Commission for the First District of the State of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1910. Public Service Commission. 1911.

- "TEN-CAR TRAINS IN SUBWAY TO-DAY; New Service Begins on Lenox Av. Line and Will Be Extended to Broadway To-morrow". The New York Times. January 23, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- The Merchants' Association of New York Pocket Guide to New York. Merchants' Association of New Yorkk. March 1906. pp. 19–26.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle Almanac. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1916. p. 119.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle Almanac. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1917 – via Hathitrust.

subway.

- "Open New Subway Lines to Traffic; Called a Triumph" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1918. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- "New Hi-Speed Locals". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. 1959. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- "Wagner Praises Modernized IRT — Mayor and Transit Authority Are Hailed as West Side Changes Take Effect". The New York Times. February 7, 1959. p. 21. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- Levey, Stanley (January 26, 1959). "Modernized IRT To Bow on Feb. 6 — West Side Line to Eliminate Bottleneck at 96th Street". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- Blakinger, Keri (June 30, 2016). "The story of Squire Vickers, the man behind the distinctive look of the New York City subway". nydailynews.com. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- Architectural League of New York (1904). Year Book of the Architectural League of New York, and Catalogue of the Annual Exhibition. Secretary of the Architectural League of New York. p. 53. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- "Subway Trains Run Again This Morning — Through Service Promised for the Rush-Hour Crowds — Tunnel Pumped Out At Last — Big Water Main That Burst Was an Old One, Pressed Into Service Again After a Five-Hour Watch". The New York Times. June 13, 1905. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Subway at Fulton Street Busy". New York Times. January 17, 1905. p. 9. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Our Subway Open, 150,000 Try It — Mayor McClellan Runs the First Official Train — Big Crowds Ride At Night — Average of 25,000 an Hour from 7 P.M. Till Past Midnight — Exercises in the City Hall — William Barclay Parsons, John B. McDonald, August Belmont, Alexander E. Orr, and John Starin Speak — Dinner at Night". The New York Times. October 28, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Historic Station Closed After 41 Years". The New York Times. January 1, 1946. p. 22. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- Grutzner, Charles (September 1, 1962). "New Platform for IRT Locals At Brooklyn Bridge to End Jams — Sharp Curve on Northbound Side Removed — Station Extended to Worth St". The New York Times. p. 42. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- "IRT Station to be Closed — East Side Subway Trains to End Stops at 18th Street". The New York Times. November 6, 1948. p. 29. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- Aciman, Andre (January 8, 1999). "My Manhattan — Next Stop: Subway's Past". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- "Subway on the East Side Will Be Opened Soon — New Switching Station on West Side Nearly Ready, Too — Football Trains On To-Day — Trains to Fulton Street in a Few Weeks Are Promised — Commission's Counsel on the Sign Question". The New York Times. November 12, 1904. p. 16. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "New Subway Station Open — Also a Short Express Service for Baseball Enthusiasts". The New York Times. April 15, 1906. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Expresses to 221st Street — Will Run in the Subway Today — New 181st Street Station Ready". The New York Times. May 30, 1906. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Era of Building Activity Opening for Fort George — New Subway Station at 191st Street and Proposed Underground Road to Fairview Avenue Important Factors in Coming Development — One Block of Apartments Finished". The New York Times. January 22, 1911. p. X11. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Trains To Ship Canal — But They Whiz by Washington Heights Stations". The New York Times. March 13, 1906. p. 16. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- "Our First Subway Completed At Last — Opening of the Van Cortlandt Extension Finishes System Begun in 1900 — The Job Cost $60,000,000 — A Twenty-Mile Ride from Brooklyn to 242d Street for a Nickel Is Possible Now". The New York Times. August 2, 1908. p. 10. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "East Side Subway Open - Train from 145th Street to Broadway in 9 Minutes and 40 Seconds". The New York Times. November 23, 1904. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 27, 2016.