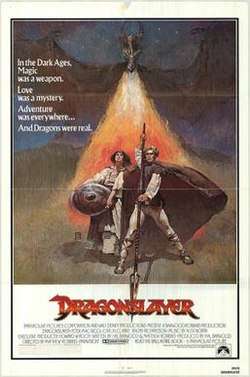

Dragonslayer (1981 film)

Dragonslayer is a 1981 American dark fantasy film directed by Matthew Robbins, from a screenplay he co-wrote with Hal Barwood. It stars Peter MacNicol, Ralph Richardson, John Hallam and Caitlin Clarke. The film is a co-production between Paramount Pictures and Walt Disney Productions: Paramount handled North American distribution while Disney's Buena Vista International handled international distribution. The story, set in a fictional medieval kingdom, follows a young wizard who experiences danger and opposition as he attempts to defeat a dragon.

| Dragonslayer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Matthew Robbins |

| Produced by | |

| Written by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Alex North |

| Cinematography | Derek Vanlint |

| Edited by | Tony Lawson |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18 million[1] |

| Box office | $14.1 million |

The second of two joint productions between Paramount and Disney (the other being Popeye), Dragonslayer was more mature than most other Disney films of the period. Because of audience expectations of the Disney name generally considered as solely children's entertainment at the time, the film's violence, adult themes and brief nudity were somewhat controversial for the company at the time even though Disney did not hold the US distribution rights. The film was rated PG in the U.S.

The special effects were created at Industrial Light and Magic, where Phil Tippett had co-developed an animation technique called go motion for The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Go motion is a variation on stop motion animation, and its use in Dragonslayer led to the film's nomination for the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects; it lost to Raiders of the Lost Ark, the only other Visual Effects nominee that year, whose special effects were also provided by ILM. Including the hydraulic 40-foot (12 m) model, 16 dragon puppets were used for the role of Vermithrax, each one made for different movements; flying, crawling, fire breathing etc.[2] Dragonslayer also marks the first time ILM's services were used for a film other than a Lucasfilm Ltd. production.

The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Score; Chariots of Fire took the award. It was also nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, once again losing to Raiders of the Lost Ark. In October 2003, Dragonslayer was released on DVD in the U.S. by Paramount Home Video.

Plot

A sixth-century post-Roman kingdom called Urland (named after the River Ur, which runs through it)[3] is being terrorized by a 400-year-old dragon named "Vermithrax Pejorative".[3] To appease the dragon, King Casiodorus offers it virgin girls selected by lottery twice a year. An expedition led by a young man called Valerian seeks the last sorcerer, Ulrich of Cragganmore, for help.

Tyrian, the brutal and cynical Captain of Casiodorus' Royal Guard, has followed the expedition. He and his lieutenant Jerbul openly intimidate the wizard, doubtful of his abilities. Ulrich invites Tyrian to stab him to prove his magical powers. Tyrian does so and Ulrich dies instantly, much to the horror of his young apprentice Galen Bradwarden and his elderly servant Hodge, who cremates Ulrich's body and places the ashes in a leather pouch. Hodge informs Galen that Ulrich wanted his ashes spread over a lake of burning water.

Galen is selected by the wizard's magical amulet as its next owner; encouraged, he journeys to Urland. On the way, he discovers Valerian is really a young woman, who is disguised to avoid being selected in the lottery. In an effort to discourage the expedition, Tyrian kills Hodge—who, just before dying, hands Galen the pouch of ashes.

Arriving in Urland, Galen inspects the dragon's lair and magically seals – he thinks – its entrance with an avalanche. Tyrian apprehends Galen and takes him to Castle Morgenthorme, from which King Casiodorus governs Urland. Casiodorus guesses that Galen is not a real wizard and complains that his attack may have angered the dragon instead of killing it, as his own brother and predecessor once did. The king confiscates the amulet and imprisons Galen. His daughter, Princess Elspeth, visits Galen—initially to taunt him. Instead, she is shocked when he informs her of rumors that the lottery is rigged; it excludes her name, and those who are rich enough to bribe the king into disqualifying their children. Her father is unable to lie convincingly when she confronts him over this.

Meanwhile, the dragon frees itself from its prison and causes an earthquake. Galen narrowly escapes from his prison, but without the amulet. The village priest, Brother Jacopus, leads his congregation to confront the dragon, denouncing it as the Devil, but the dragon incinerates him and then heads for the village of Swanscombe, burning all in its path.

When the lottery begins anew, Elspeth rigs the draw so that only her name can be chosen. Consequently, King Casiodorus returns the amulet to Galen so that he might save Elspeth. Galen uses the amulet to enchant a heavy spear that had been forged by Valerian's father (which he had dubbed Sicarius Dracorum, or "Dragonslayer") with the ability to pierce the dragon's armored hide. Valerian gathers some molted dragon scales to create a shield for Galen. Valerian laments now that her gender cover is blown, she'll be eligible for the lottery since she herself is still a virgin, and that Galen has fallen in love with Princess Elspeth. Galen admits he has fallen in love, but it's Valerian, not Elspeth, he's in love with. The couple kiss, thus realizing their romantic feelings for each other.

Attempting to rescue Elspeth, Galen fights Tyrian and kills him emerging victorious. The Princess, however, is determined to make amends for all the girls whose names have been chosen in the past; she descends into the dragon's cave and to her death. Galen follows her and finds a brood of young dragons feasting on her corpse. He kills them and finds Vermithrax resting by an underground lake of fire. He manages to wound the dragon, but the spear is broken. Only Valerian's shield saves him from incineration.

After his failure to kill Vermithrax, Valerian convinces Galen to leave Swanscombe with her. As both prepare to depart, the amulet gives Galen a vision which explains his teacher's final wishes: He used Galen to deliver him to Urland. Ulrich had asked that his ashes be spread over "burning water", which is in the dragon's cave. Galen realizes that the wizard had planned his own death and cremation, realizing he was too old and frail to make the journey.

Galen returns to the cave. When he spreads the ashes over the fiery lake, the wizard is resurrected within the flames. Ulrich reveals that his time is short and that Galen must destroy the amulet "when the time is right". The wizard then transports himself to a mountaintop, where he summons a storm and confronts Vermithrax. After a brief battle, the monster snatches the old man and flies away with him. Cued by Ulrich, Galen crushes the amulet with a rock. The wizard's body explodes and kills the dragon, whose corpse falls out of the sky.

In the aftermath, villagers inspecting the wreckage credit God with the victory. The king arrives and drives a sword into the dragon's broken carcass to claim the glory for himself. As Galen and Valerian leave Urland together, he confesses that he misses both Ulrich and the amulet. He says, "I just wish we had a horse." Suddenly, a white horse appears, and the couple use the horse to ride away.

Cast

- Peter MacNicol as Galen Bradwarden

- Caitlin Clarke as Valerian

- Ralph Richardson as Ulrich of Cragganmore

- John Hallam as Tyrian

- Peter Eyre as King Casiodorus

- Albert Salmi as Greil (dubbed by Norman Rodway)

- Sydney Bromley as Hodge

- Chloe Salaman as Princess Elspeth

- Emrys James as Simon (Valerian's Father)

- Roger Kemp as Horsrick, Casiodorus's Chamberlain

- Ian McDiarmid as Brother Jacopus

Production

Conception

According to Hal Barwood, he and Matthew Robbins got the inspiration for Dragonslayer from The Sorcerer's Apprentice sequence in Fantasia, and later came up with a story after researching St. George and the Dragon. Barwood and Robins rejected the traditional conceptions of the medieval world in order to give the film more realism: "our film has no knights in shining armor, no pennants streaming in the breeze, no delicate ladies with diaphonous veils waving from turreted castles, no courtly love, no holy grail. Instead we set out to create a very strange world with a lot of weird values and customs, steeped in superstition, where the clothes and manners of the people were rough, their homes and villages primitive and their countryside almost primeval, so that the idea of magic would be a natural part of their existence." For this reason, they chose to set the film after the Roman departure from Britain, prior to the arrival of Christianity. Barwood and Robins began to hastily work on the story outline on June 25, 1979 and completed in early August. They received numerous refusals from various film studios, due to their inexperience in budget negotiations. The screenplay was eventually accepted by Paramount Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, becoming the two studios' second joint effort after the 1980 film Popeye.[3]

Dragon design and realization

Twenty-five percent of the film's budget went into the special effects to bring the dragon to life. Graphic artist David Bunnett was assigned to design the look of the dragon, and was fed ideas on the mechanics on how the dragon would move, and then rendered the concepts on paper. It was decided early on in production that as the film's most important sequence would have been the final battle, it was deemed necessary to design a dragon with an emphasis on its flying abilities. Bunnett also designed the dragon to have a degree of personality, deliberately trying to avoid creating something like the titular creature from Alien, which he believed was "too hideous to look at".[3]

After Bunnett handed his storyboard panels to the film crew, it was decided that the dragon would have to be realized with a wide variety of techniques: the resulting dragon on film is a composite of several different models. Phil Tippett of ILM finalized the dragon's design, and sculpted a reference model which Danny Lee of Disney Studios closely followed in constructing the larger dragon props for closeup shots. Two months later, Lee's team finished building a sixteen-foot head and neck assembly, a twenty-foot tail, thighs and legs, claws capable of grabbing a man, and a 30-foot-wide (9.1 m) wing section. The parts were flown to Pinewood Studios outside London in the cargo hold of a Boeing 747.[3]

Brian Johnson was hired to supervise the special effects, and began planning both on and off-set effects with various special effects specialists. Dennis Muren, the effects cameraman, stated, "We knew the dragon had a lot more importance to this film than some of the incidental things that appeared in only a few shots in Star Wars or The Empire Strikes Back. The dragon had to be presented in a way that the audience would be absolutely stunned."[3]

After the completion of principal shooting, a special effects team of eighty people at ILM studios in northern California worked eight months in producing 160 composite shots of the dragon. Chris Walas sculpted and operated the dragon head used for close-up shots. The head measured eight feet in length. The model was animated by a combination of radio controls, cable controls, air bladders, levers and by hand, thus giving the illusion of a fully coordinated face with a wide range of expression.[3] Real WW2 era flamethrowers were used for the dragons fire breathing effects. The animals used for the dragon's vocalizations included lions, tigers, leopards, jaguars, alligators, pigs, camels, and elephants.

Phil Tippett built a model for the scenes in which the dragon would be required to walk. Tippett did not want to use standard stop motion animation techniques, and had his team build a dragon model which would move during each exposure rather than in between as was once the standard. This process, named "go motion" by Tippett, recorded the creature's movements in motion as a real animal would move, and removed the jerkiness common in prior stop motion films.[3]

Ken Ralston was assigned to the flying scenes. He built a model with an articulated aluminum skeleton in order to give it a wide range of motion. Ralston shot films of birds flying in order to incorporate their movements into the model. As with the walking dragon, the flying model was filmed using go-motion techniques. The camera was programmed to tilt and move at various angles in order to convey the sensation of flight.[3]

Casting

Peter MacNicol first met Robbins while waiting to audition for the pilot film of Breaking Away, and agreed to take part in Dragonslayer, despite having a dislike for performing magic tricks. MacNicol had to learn horse riding, both English style and bareback for the role. MacNicol found this difficult, saying that "They took away my stirrups, they took away my reins and whipped the horse, and then they told me to windmill my arms and turn a complete circle in the saddle. Then they took away the saddle!" He later took on vocal coaching in order to disguise his Texas accent, and took magic lessons from British prestidigitator Harold Taylor, who had previously performed for the British royal family.[3]

Caitlin Clarke was initially hesitant to involve herself in the film, as she was preparing to audition for a play in Chicago. Her agent insisted, though, and after doing an audition tape, was called back for more tests. Clarke failed them, but managed to pass after doing another test at Robbins' insistence. She got on well with Ralph Richardson, and stated that he taught her more in one rehearsal than in years of acting classes.[3]

Set design

Elliot Scott was hired to design the sets of the film's sixth-century world. He temporarily converted the 13th-century Dolwyddelan Castle into Ulrich's ramshackle sixth-century fortress, much to the surprise of the locals. Next, Scott built the entire village of Swanscombe on a farmside outside London. Although Scott extensively researched medieval architecture in the British Museum and his own library, he took some artistic liberties in creating the thatched roof houses, the granary, Simon's house and smithy and Casiodorus' castle, as he was unable to find enough information on how they would look exactly. Scott then built the interior of the dragon's lair, using 25,000 cubic feet (710 m3) of polystyrene and 40 tons of Welsh slate and shale. The shots of the Welsh and Scottish landscapes were extended through the use of over three dozen matte paintings.[3]

Shooting locations in North Wales

Nearly all of the outdoor scenes were shot in North Wales. The final scene was shot in Skye, Scotland.

- The filming crew were based in Betws y Coed, and the artists were stabled further down the Conwy valley.

- Dolwyddelan Castle was used for all outdoor shots of Ulrich's Castle. This includes the arrival of the delegation from Urland, the arrival of guards from Urland, Ulrich's first death scene and funeral burning. Many locals were hired as extras during this scene.

- The external long shots of the dragon's lair were of the main face of Tryfan, within yards of the A5, opposite Llyn Ogwen. The lair was shot looking upwards from the road, towards the broken face of Tryfan, Nant Ffrancon.

- Shots of Galen and Hodge on the trek to Urland were shot on the old road from Cobdens to Bryn Engan, in Capel Curig.

- The early morning camping scenes on the trek to Urland, Tyrian's shooting of Hodge, and Hodge's death scene all take place on a 500-yard (500 m) section of Fairy Glen between Betws-y-Coed and Penmachno.

- The scenes of the delegation crossing over into Urland were shot above Ogwen Cottage, Nant Ffrancon.

- Galen fleeing on horseback from Casiodorus's castle was shot high above Llyn Crafnant.

- The scene where the party cross a wooden bridge below a waterfall was shot at the foot of Cwmorthin Slate Quarry

- The scene where Galen Bradwarden sees an apparition in the lake was shot at the bottom end of Llyn Crafnant.

- The bleak rocky outcrop where Valerian gathers Dragon scales is Castell y Gwynt, above the Pen-y-Gwryd hotel.

- The scenes where Valerian delivers a shield made from the Dragon's scales and the intimate scene between Valerian and Galen were shot in the boulder field below Tryfan, about 300 yards from the A5 near the Llyn Ogwen Car Park.

- The procession scenes in which victims are transported to the Dragon's lair were shot on Gelli behind the main shop in Capel Curig.

- Vermithrax crashes into Llyn Llydaw, below Snowdon.

Costumes

The costumes were designed by Anthony Mendelson, who consulted the British Museum, the London Library and his own reference files in order to make the clothing evoke the designs of the early Middle Ages. Mendelson designed the costumes to be roughly stitched and the utilized colors were only ones which would have been possible with the vegetable dyes then in use. The costumes of Casiodorus and his court were designed of fine silk, as opposed to the coarsely woven clothes of the Urlanders.[3]

Music

The film's Academy Award-nominated score was composed by Alex North. The score's linear conception was developed through transparently layered, polyphonic orchestral texture dominated by a medieval-style modal harmony. The score was largely based on five major thematic concepts:

- the suffering of the Urlanders;

- a "magic" motif;

- the amulet;

- the sacrificial virgins;

- the relationship between Galen and Valerian.

North had six weeks to compose the score,[5] which featured music rejected from his score for Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. (The opening sequence of Dragonslayer features a reworking of North's original music for the opening of the "Dawn of Man" sequence—which in the final film was played without music—and a waltz representing the dragon in flight was a variation of the cue "Space Station Docking", which in the final cut of 2001 was replaced by The Blue Danube).[6] North was disappointed by the resulting dragon scenes, as they did not use the entirety of the pieces he composed for them. He later stated that he had written "a very lovely waltz for when the dragon first appears, with just a slight indication that this may not be a bad dragon." The waltz was scrapped in favor of tracks used earlier in the movie.

Despite the omission of the dragon-reveal waltz, the score was widely praised. Pauline Kael wrote in the New Yorker that the score was a "beauty", and that "at times, the music and the fiery dragon seem one". Royal S. Brown of Fanfare Magazine praised the soundtrack as "one of the best scores of 1981".[7]

Reception

Box office

The film grossed just over $14 million in the US[8] with an estimated budget of $18 million. Despite its mediocre box office performance, it later became a cult film.[9] At the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an 87% score based on 30 reviews, with an average rating of 6.66/10. The site's critics consensus reads, "An atypically dark Disney adventure, Dragonslayer puts a realistic spin — and some impressive special effects — on a familiar tale."[10] At Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 68 out of 100 based on 13 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[11]

Critical response

– Von Gunden, Kenneth Flights of Fancy: The Great Fantasy Films, McFarland, 1989, ISBN 0-7864-1214-3

Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert both gave the film three stars out of four in their respective print reviews.[12][13] Siskel praised the "dazzling special effects" and the "convincing portrait by Ralph Richardson of the aged magician Ulrich",[12] and Ebert called the scenes involving the dragon "first-rate".[13]

Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called Vermithrax "the greatest dragon yet", and praised the film for its effective evocation of the Dark Ages.[14]

David Denby of New York praised Dragonslayer's special effects and lauded the film as being much better than Excalibur and Raiders of the Lost Ark.[14]

The film was not without its criticism. David Sterritt of The Christian Science Monitor, although praising the sets and pacing of the film, criticised it for lack of originality, stressing that MacNicol's and Richardson's characters bore too many similarities to the heroes of Star Wars. A similar critique was given by John Coleman of the New Statesman, who called the film a "turgid sword-and-sorcery fable, with Ralph Richardson in a backdated kind of Star Wars of Alec Guinness role."[14]

Tim Pulleine of the Monthly Film Bulletin criticized the film's lack of narrative drive and clarity to supplement the special effects.[14] Upon the film's first television broadcast, Gannett News Service columnist Mike Hughes called the story "slight" and "slow-paced", but admired a "lyrical beauty to the setting and mood".[15] Nonetheless, he warned: "In movie theaters, that came across wonderfully; on a little TV screen, this may be strictly for specialized tastes."[15]

Alex Keneas of Newsday criticized the film for being too focused on superstition, and for being "bereft of any sense of medieval time, place and society".[14]

Christopher John reviewed Dragonslayer in Ares Magazine #10 and commented that "Though the dialogue is occasionally stiff, there is a believable reality. When the people and setting of a fantasy are as carefully wrought as they are here, it is easy to get an audience to accept as small and wonderful a thing as a dragon."[16]

Vermithrax Pejorative

Guillermo del Toro has stated that along with Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty, Vermithrax is his favorite cinematic dragon.[17] He further stated that:

One of the best and one of the strongest landmarks [of dragon movies] that almost nobody can overcome is Dragonslayer. The design of Vermithrax Pejorative is perhaps one of the most perfect creature designs ever made.[18]

A Song of Ice and Fire author George R. R. Martin once ranked the film the fifth best fantasy film of all time, and called Vermithrax "the best dragon ever put on film", and the one with "the coolest dragon name as well".[19] Vermithrax is mentioned in a list of dragons' names in the fourth episode of the television adaptation to Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire book series.[20] Fantasy author Alex Bledsoe stated that:

...everyone has a 'first dragon', the one that awoke their sense of wonder about the creatures. For many it's Anne McCaffrey's elaborate world of Pern, where genetically-engineered intelligent dragons bond with their riders; for others it's Smaug in The Hobbit, guarding his hoard deep in a cave. But for me, it was the awesome Vermithrax from the 1981 film, Dragonslayer.[21]

During filming of Return of the Jedi, in which Ian McDiarmid, who portrays minor character Brother Jacopus in Dragonslayer, stars as the film's main antagonist, Emperor Palpatine, the ILM crew jokingly placed a model of one of the dragons from Dragonslayer in the arms of the Rancor model and took a picture. The picture was included in the book Star Wars: Chronicles. A creature based on the appearance of this dragon appears in one of Jabba the Hutt's creature pens in Inside the Worlds of Star Wars Trilogy.

Related media

Novelization

A novelization Dragonslayer was written by Wayland Drew that delves deeper into the background of many of the characters. Expansions upon the film's plot include details such as these:

- Galen has (or at least had) an elder sister named Apulia.

- As an infant, Galen was handed to Ulrich by his parents due to their fear of his magical abilities. Ulrich took him as an apprentice, but was concerned with the lad's lack of focus, which usually resulted in the unintentional creation of bizarre, dream-inspired creatures.

- The other Sorcerers of Cragganmore are mentioned; Ulrich was the apprentice of Belisarius, who was the apprentice of Pleximus.

- A vision glimpsed by Ulrich in his scrying bowl implies that sorcerers could have been responsible for the creation of dragons, and that whoever this sorcerer was, he had far more power than Ulrich. This is only briefly alluded to in the film. It is further mentioned that the sorcerer who created dragons also fashioned the magical amulet which Galen wears through most of the story.

- Urland's neighbor-kingdoms of Anwick, Cantware, and Heronsford are mentioned.

- The revelation that Vermithrax, while physically androgynous, nevertheless required copulation with another dragon for fertilization.

- Swanscombe's neighbor-villages of Nudd, Turnratchit, and Veryemere are mentioned.

- It is revealed that the lottery's standards for eligibility fluctuated, and several married women and mothers were sacrificed too, Valerian's mother being among them. Her death was the price Simon had to pay in order to fashion Sicarius Dracorum, which was done with the assistance of Ulrich himself.

- Two major rivers besides Ur are mentioned: Swanscombe and Varn.

- Simon is revealed to be a master blacksmith who fashioned highly prized weapons and armor. It was the toll of seeing so many use his arms and armor only to be killed by the dragon that convinced him to stop forging arms and armor.

- King Casiodorus is revealed to be of Roman heritage, and is portrayed as contemptuous toward his largely Saxon subjects, whom he views as superstitious and backward.

- Ulrich is revealed to have extensive research and history of dragons. When he reviews his library to determine which dragon it is that is terrorizing Urland, he discovers (to his horror) that it is Vermithrax, unlike the movie which has him knowing all along.

- When Ulrich is asking about other wizards which might still be alive to assist Valerian, he mentions Prospero, from Shakespeare's "The Tempest". Valerian gives a (brief) update of Prospero's fate which corresponds to the Shakespearean storyline.

Marvel Comics adaptation

Marvel Comics published a comic book adaptation of the film by writer Dennis O'Neil and artists Marie Severin and John Tartaglione in Marvel Super Special #20.[22][23]

SPI board game

Simulations Publications, Inc. produced the board game of the same name, designed by Brad Hessel and Redmond A. Simonsen.[24]

Soundtrack

Australian label Southern Cross initially released an unauthorized soundtrack album in 1983 on LP (a boxed audiophile pressing, at 45 rpm), and in 1990 on CD. That album appeared on iTunes for a limited time. The first official and improved CD release came in 2010 by U.S. label La-La Land Records. The new album featured newly mastered audio from the original LCR(Left-Center-Right)-mix and included previously unreleased source music and alternative takes.

See also

References

- Harmetz, Aljean (September 9, 1981). "HOLLYWOOD IS JOYOUS OVER ITS RECORD GROSSING SUMMER". The New York Times. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- Ronan, Margaret (1981), "The Vermithrax Pejorative Story: Behind the Scenes at the Making of Dragonslayer", Weird Worlds

- Fingeroth, Danny, 1981, The Making of Dragonslayer in Dragonslayer - The Official Marvel Comics Adaptation of the Spectacular Paramount/Disney Motion Picture!, Marvel Super Special, 1, 20, Marvel Comics Group, 1981

- Vermithrax Pejorative, Monster Legacy (April 14, 2013)

- Henderson, Kirk (1994). "Alex North's 2001 and Beyond". Soundtrack Magazine. 13 (49). Archived from the original on September 11, 2013.

- Rosar, William H. (1987). "Notes on Dragonslayer". CinemaScore Magazine. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013.

- Shoilevska, Sanya; Williams, John (2003). Alex North, film composer. McFarland. ISBN 0786414707.

A biography, with musical analyses of a Streetcar Named Desire, Spartacus, The Misfits, Under the Volcano, and Prizzi’s Honor.

- Dragonslayer (1981)

- Schmidt, Sara (July 21, 2016). "15 Best Dragon Movies Of All Time". ScreenRant.com. Screen Rant. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- "Dragonslayer (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- "Dragonslayer (1981) Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Siskel, Gene (June 30, 1981). "Dragonslayer". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 2.

- Ebert, Roger. "Dragonslayer". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- Von Gunden, Kenneth Flights of Fancy: The Great Fantasy Films, McFarland, 1989, ISBN 0-7864-1214-3

- Hughes, Mike (July 25, 1986). "'C.A.T. Squad' script puts it above rest". Argus-Leader. Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Gannett News Service. p. 3B. Archived from the original on April 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- John, Christopher (September 1981). "Film & Television". Ares Magazine. Simulations Publications, Inc. (10): 13, 29.

- "An Unexpected Party Chat transcript now available!". Weta Holics. July 30, 2008. Archived from the original on July 29, 2008.

- "Guillermo del Toro gives Hobbit update". ComingSoon.net. Evolve Media, LLC. November 12, 2008. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- "George R.R. Martin's Top 10 Fantasy Films". The Daily Beast. April 11, 2011. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Garcia, Elio (May 27, 2011). "Easter Eggs for the Fans". Suvudu. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Bledsoe, Alex (August 17, 2009). "First Dragons: Vermithrax from ‘Dragonslayer’". AlexBledsoe.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- "Marvel Super Special #20". Grand Comics Database.

- Friedt, Stephan (July 2016). "Marvel at the Movies: The House of Ideas' Hollywood Adaptations of the 1970s and 1980s". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (89): 65.

- Dragonslayer at Board Game Geek

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dragonslayer (1981 film) |