Djemal Pasha

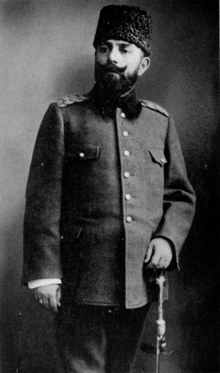

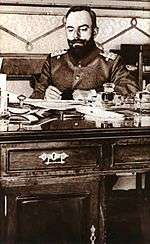

Ahmed Djemal Pasha (Ottoman Turkish: احمد جمال پاشا, romanized: Ahmet Cemâl Paşa; 6 May 1872 – 21 July 1922), commonly known as Jamal Basha as-Saffah or Jamal Pasha the Bloodthirsty in the Arab world, was an Ottoman military leader and one-third of the military triumvirate known as the Three Pashas (also called the "Three Dictators") that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I and carried out the Armenian Genocide. Djemal was the Minister of the Navy.

Ahmed Djemal Pasha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 May 1872 Midilli, Vilayet of the Archipelago, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 21 July 1922 (aged 50) Tbilisi, Georgian SSR |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1893–1918 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | Minister of the Navy |

| Commands held | Fourth Army |

| Battles/wars | Balkan Wars, Sinai and Palestine Campaign, Mesopotamian Campaign (1915–1917) |

| Other work | Revolutionary, despot |

Biography

Ahmed Djemal was born in Mytilene, Lesbos, to Mehmet Nesip Bey, a military pharmacist.

Destined for the army, Djemal graduated from Kuleli Military High School in 1890. He went on to the Military Academy (Mektebi Harbiyeyi Şahane), the staff college in Istanbul, in 1893. He was posted to serve with the 1st Department of the Imperial General Staff (Seraskerlik Erkânı Harbiye), and then he worked at the Kirkkilise Fortification Construction Department bound to Second Army. Djemal was assigned to the II Corps in 1896; being appointed two years later, the staff commander of Novice Division, stationed on the Salonica frontier.

Meanwhile, he began to sympathize with the reforms of Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) on military issues. It was in 1905 that Djemal was promoted to major and designated Inspector of Roumelia Railways. The following year he signalled his democratic credentials and joined the Ottoman Liberty Society. He became influential in the department of military issues of the Committee of Union and Progress. He became a member of the Board of the III Corps in 1907. Here, he worked with future Turkish statesmen Major Fethi (Okyar) and Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), although Atatürk soon developed a rivalry with Djemal Pasha and his colleagues over their policies after they seized power in 1913.[1][2] Between 1908 and 1918, Djemal was one of the most important leaders of the Ottoman government.

His grandson Hasan Cemal is a well-known columnist, journalist and writer in Turkey.[3]

Balkan Wars

In 1911, Djemal was appointed Governor of Baghdad. He resigned to rejoin the army in the Balkan Wars on the Salonica front line, attempting to bolster Turkey's European possessions from encroachment.[4] In October 1912, he was promoted to colonel. At the end of the First Balkan War, he played an important role in the propaganda drawn up by the CUP against negotiations with the victorious European countries. He tried to resolve the problems that occurred in Constantinople after the Bab-ı Ali Attack (Coup of 1913). Djemal played a significant role in the Second Balkan War, and with the revolution of the CUP on 23 January 1913, he became the commander of Constantinople and was appointed Minister of Public Works. In 1914 he was promoted as the Minister of the Navy.

World War I and Armenian Genocide

When Europe was divided into two blocs before the First World War, he supported an alliance with France. He went to France to negotiate an alliance with the French, but failed and then sided with Enver and Talaat, who favoured the German side. Djemal, along with Enver and Talaat, took control of the Ottoman government in 1913. The Three Pashas effectively ruled the Ottoman Empire for the duration of World War I and were the three main perpetrators of the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian genocides. Djemal was one of the designers of the government's internal and foreign policies, nearly all of which proved disastrous for the Empire. For example, his policy to oppose the powers in Eastern Europe caused a dramatic escalation and the 'balkanisation' of the Slavic republics. Multiple contradictory allegiances in a redundant balance-of-powers strategy added immense complexity and immeasurable difficulties to Ottoman logistics across thousands of miles of desert.

After the Ottoman Empire declared war on the Allies in World War I, Enver Pasha nominated Djemal Pasha to lead the Ottoman army against British forces in Egypt, and Djemal accepted the position. Previously snubbed by the Allies, Djemal switched his attention to an alliance with the Central Powers, although he had at first been opposed to a full alliance with Germany. Nevertheless, he agreed in early October 1914 to use his ministerial powers to authorise Admiral Souchon to launch a pre-emptive strike in the Black Sea, which led to Russia, Britain and France declaring war on the Ottoman Empire a few days later.

Governor of Greater Syria

Djemal Pasha was appointed with full powers in military and civilian affairs as Governor of Syria in 1915. A provisional law granted him emergency powers in May of that year. All cabinet decrees from Constantinople concerning Syria became subject to his approval. His offensives on both his first and second attacks on the Suez Canal failed. Coupled with the wartime exigencies and natural disasters that afflicted the region during these years, this alienated the population from the Ottoman government, and led to the Arab Revolt. In the meantime, the Ottoman army usually commanded by Colonel Kress von Kressenstein pushed towards and occupied Sinai. The two men had a thinly disguised contempt for each other, which weakened the command.[5]

He was known among the local Arab inhabitants as al-Saffah, "the Blood Shedder", being responsible for the hanging of many Lebanese, Syrian Shi'a Muslims and Christians wrongly accused of treason on 6 May 1916 in Damascus and Beirut.[6]

In his political memoirs, the leader of the "Beirut Reform Movement" Salim Ali Salam recalls the following:

Jamal Pasha resumed his campaign of vengeance; he began to imprison most Arab personalities, charging them with treason against the State. His real intent was to cut off the thoughtful heads, so that, as he put it, the Arabs would never again emerge as a force, and no one would be left to claim for them their rights … After returning to Beirut [from Istanbul], I was summoned … to Damascus to greet Jamal Pasha … I took the train … and upon reaching Aley we found that the whole train was reserved for the prisoners there to take them to Damascus … When I saw them, I realized that they were taking them to Damascus to put them to death. So … I said to myself: how shall I be able to meet with this butcher on the day on which he will be slaughtering the notables of the country? And how will I be able to converse with him? … Upon arriving in Damascus, I tried hard to see him that same evening, before anything happened, but was not successful. The next morning all was over, and the … notables who had been brought over from Aley were strung up on the gallows.[7]

During 1915-1916, Djemal had 34 political opponents executed as martyrs.[8]

At the end of 1915, Djemal with viceregal powers is said to have started secret negotiations with the Allies for ending the war; he proposed to take over the Ottoman administration himself as an independent King of Syria. These secret negotiations came to nothing, in part because the Allies reportedly could not agree on the future territory of the Ottoman Empire; France objected strongly, and Britain was unwilling to fund the Imperial operations.[9] In a new interpretation, historian Sean McMeekin casts doubt on the tradition that Djemal made any such overtures to the Allies. The Pasha was an outspoken critic of the Allies, collaborated fully with the German army, and grew to hate the British Empire.[10]

His most successful military exploit was against the British Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force, which had arrived in early 1915 from India. 35,000 British troops marched north on Baghdad, hoping to take the citadel with relatively few casualties. Djemal Pasha was appointed to command and marshalled a vast army, ultimately led by General Halil Kut, which by the time of the siege of Kut al-Amara numbered 200,000 Turks and Arab auxiliaries. The British could only evacuate their wounded with Djemal's consent and attempted to send emissaries requesting permission to evacuate while the city was encircled on three sides. Djemal refused to compromise his advantageous position, and strafed enemy attempts by the Tigris Corps to take relief boats up river. They had underestimated Djemal's considerable administrative capabilities and will to resist the Allied armies. The Ottoman troops fought hard at the Battle of Ctesiphon, but the subsequent fate of POWs and civilians later enhanced Djemal Pasha's wartime reputation as a capricious and cruel general. Nonetheless, the successes impressed T. E. Lawrence to write a significant account of their diplomatic encounters when finally Kut fell in April 1916, which provides for "a colourful character".[11]

The ever-present threat of Arab Revolt fomented by British intelligence was rising throughout 1916 and 1917. Djemal instituted strict control over Syria Province against Syrian opponents. Djemal's forces also fought against the Arab nationalists and Syrian nationalists from 1916 onwards.[12] Ottoman authorities occupied the French consulates in Beirut and Damascus and confiscated French secret documents that revealed evidence about the activities and names of the Arab insurgents. Djemal used the information from these documents as well as from others belonging to the Decentralization Party. He believed that insurgency under French control was the main reason for his military failings. With the documents he gathered, Djemal moved against the insurgent forces which were led by Arab political and cultural leaders. This was followed by the military trials of the insurgents known as Âliye Divan-ı Harb-i Örfisi in which they were punished.

Commander of Fourth Army

Gaza's head of garrison, Major Tiller, had 7 infantry battalions, a cavalry squadron, and some camel troops. The British under Colonel Chetwode already had 2,000 troops in front of the city. Reluctantly, Djemal marched with the 33rd Division to relieve Gaza. Kressenstein was delighted to have repelled the British assault and wanted to mobilise aggressively by driving into Shellal, Wadi Ghazze, and Khan Yunis, but Djemal absolutely forbade it. The British had a whole division in retreat, so Djemal apprehended that a two-battalion sortie would have been annihilated.[13] One of Djemal's associates in Iraq was engineer Colonel Heinrich August Meissner who had built both the Hejaz and Baghdad railways and who was employed on an ambitious project to construct a railway to the Suez canal at Bir Gifgafa. By October 1915, the Central Powers had already built 100 miles of track as far as the oasis of Beersheba. Djemal insisted that an extended railway would be needed to attack British Egypt.

Djemal was completely committed to the Turko-German military machine, and Britain would not relinquish its ambitions to control Syria.[14] Kemal and Djemal became increasingly sceptical of German capabilities, but Djemal was not yet prepared to openly back the German allies. He insisted on the possibility of a planned allied assault behind the Yıldırım Army, as the Seventh Army gathered at the Turco-German Aleppo Conference.[15] In the shake-up that followed, Djemal was demoted to a command of the Fourth Army under General Erich von Falkenhayn. They now adopted a plan similar to the Kress Plan for Gaza and sent the Yıldırım Army to Baghdad. It was not until October 1917 that the Seventh Army could march south to face the growing threat from Allenby, hampered by the limitations of the single-gauge railway, which was built away from the coastline to avoid Royal Navy salvos.

On 7 November, the British captured Gaza, but Djemal had long since been forced to evacuate. Although chased, he managed to retreat at speed.[16] In December, the Turks were driven out of Jaffa, Djemal's army still in retreat, and the city fell without a fight. Falkenhayn had ordered an evacuation on 14th, and the enemy had begun to enter the same day.[17] But now the Turkish Eighth formed a much stronger line of entrenchment; Djemal's organized defence of Gaza had been amply anticipated by the British. His army delayed them further at the vital Junction railway station. But the British were probably unaware of its importance.

The fighting in the hills was all but over by 1 December. On 6 December, Djemal Pasha was in Beirut to make a speech publicizing the allied deal to 'carve up' Syria-Palestine into partitioned spheres of influence in the Sykes-Picot agreement.[18][19] At the end of 1917, Djemal ruled from his post in Damascus as a near-independent ruler of his portion of the Empire. But he had resigned from the 4th Army and returned to Istanbul. On 9 April and then 19 April 1918, Djemal ordered the evacuation of civilians from Jaffa and Jerusalem. The Germans were furious and rescinded the order, revealing the chaos in the Ottoman Empire. Djemal's ambiguous attitude to the subject populations played into the hands of British rule. The Turkish line was solidified in readiness for the final onslaught at Nebi Samwell and Nahr-el-Auja. To the south of Nebi were the defences of Beit Iksa; the Heart and Liver Redoubts before Lifa; and Deir Yassin, two systems behind Ain Karim. In all, there were 4 miles of fortifications.[20]

Parliament

In the last congress of Committee of Union and Progress held in 1917, Djemal was elected to the Board of Central Administration.

With the defeat of the empire in October 1918 and the resignation of Talaat Pasha’s cabinet on 2 November 1918, Djemal fled[21] with seven other leaders of the CUP to Germany, and then Switzerland.

Military trial and assassination

A military court in Turkey accused Djemal of persecuting Arab subjects of the Empire and sentenced him to death in absentia. Later in 1920, Djemal went to Central Asia, where he worked on modernising the Afghan army.[22] Due to the success of the Bolshevik Revolution, Djemal travelled to Tiflis to act as a military liaison officer to negotiate over Afghanistan with the Soviets. Together with his secretary, he was assassinated on 21 July 1922 by Stepan Dzaghigian, Artashes Gevorgyan, and Petros Ter Poghosyan, as part of Operation Nemesis, in retribution for his role in the Armenian Genocide and the First World War. Djemal's remains were brought to Erzurum and buried there.

References

- Barry M. Rubin; Kemal Kirişci (1 January 2001). Turkey in World Politics: An Emerging Multiregional Power. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-55587-954-9.

- Muammer Kaylan. The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey. Prometheus Books, Publishers. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-61592-897-2.

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (28 October 2014). World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [5 volumes]: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099658.

- Djemal, Memories; Kress, Zwischen Kaukasus und Sinai; RUSI journal 6, p.503-13; Grainger, Battle for Palestine, p.17

- Cleveland, William: A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder: Westview Press, 2004. "World War I and the End of the Ottoman Order", 146–167.

- Salibi, K. (1976). "Beirut under the Young Turks: As Depicted in the Political Memoirs of Salim Ali Salam (1868–1938)," In J. Berque, & D. Chevalier, Les Arabes par leurs archives: XVIe-XXe siecles. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Elie Kedourie, England and the Middle East, pp.62-4

- Fromkin, David, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East]. New York: Avon Books, 1989, p. 214.

- McMeekin, Sean (2011). "The Russian Origins of the First World War". Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press: 198–201. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

- Provence, Michael (2005). The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism. University of Texas Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-292-70680-4.

- Grainger, p.35

- Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace, p.214-15; P G Weber, Eagles on the Crescent, pp.107 and 153-4; Grainger, p.69-70

- Djemal, pp.183-4

- Official History, 2.1.75; Grainger, p.149

- Grainger, p.173-5

- Kedourie, The Middle East, p.

- Grainger, p.202

- Grainger, p.202-3

- Findley, Carter Vaughn (2010). "Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity". Yale University Press: 215. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Adamec, Ludwig W. (1974). Afghanistan's Foreign Affairs to the Mid-Twentieth Century: Relations with the USSR, Germany, and Britain. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-81650-459-8.

Bibliography

- Aaronson, A. (1917). With the Turks in Palestine. London.

- Ajay, A. (1974). "Political intrigue and suppression in Lebanon during WWI". International Journal of Middle East Studies.

- Anderson, Scott (2014). Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Anchor Books.

- Benson, A. (1918). Crescent and the Iron Cross. London.

- Benz, Wolfgang (2010). Vorurteil und Genozid. Ideologische Prämissen des Völkermords (in German). Böhlau Verlag.

- Cleveland, William (2004). A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Djemal Pasha, Ahmed (1922), Memories of a Turkish statesman: 1913–1919, London and New York: George H. Doran Company

- Erickson, E.J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Westport, CT.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn (2010). Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity. Yale University Press.

- Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: Avon Books.

- G G Gilbar, ed. (1990). Ottoman Palestine. London.

- Haddad, W.W.; Ochsenwald, W. (1977). Nationalism in a Non-Nationalist State: The Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Columbus, OH.

- Howard, H.N. (1966). The Partition of Turkey: A Diplomatic History, 1913-1923. Norman, OK.

- von Kressenstein, F Kress (1921). "Zwicken Kaukasus und Sinai". Jahrbuch des Bundes der Aisenkampfer (in German).

- von Kressenstein, F Kress (1938). Mit dem Turken zum Suezkanal (in German). Berlin.

- Lawrence, T.E. (1976). Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph (5th ed.). London.

- Mango, Andrew (1999). Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press. ISBN 1-58567-011-1.

- McMeekin, Sean (2011). "The Russian Origins of the First World War". Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Orga, Irfan (1958). Phoenix Ascendant: The Rise of Modern Turkey. London.

- Provence, Michael (2005). The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70680-4.

- Ramsaur, E.E. (1957). The Young Turks: the Prelude to the Revolution of 1908. New York.

- Rubin, Barry M.; Kemal Kirişci (1 January 2001). Turkey in World Politics: An Emerging Multiregional Power. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55587-954-9.

- Salibi, K.; Berque, J.; Chevalier, D. (1976). "Beirut under the Young Turks: As Depicted in the Political Memoirs of Salim Ali Salam (1868–1938)". Les Arabes par leurs archives: XVIe-XXe siecles. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Off Hist. - Sir G MacMunn and C Falls, Official History:'Military Operations, Egypt and Palestine', vol.2 (2 of 3 vols) London, 1930.

- Yildrims - Hussein Husni Amir Bey, trans. Captain C Channer (typescription IWM).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Djemal Pasha |

![]()

- "Jemal, Ahmed". Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- "Assassination of Djemal Pasha". Milwaukee Armenian Community. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Newspaper clippings about Djemal Pasha in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Hasan Kayali: Cemal Pasa, Ahmed, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.