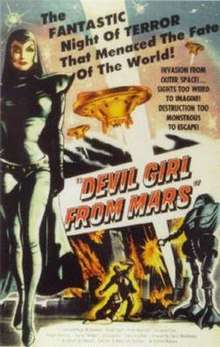

Devil Girl from Mars

Devil Girl from Mars is a 1954 UK black-and-white science fiction film, produced by the Danziger Brothers, directed by David MacDonald and starring Patricia Laffan, Hugh McDermott, Adrienne Corri, and Hazel Court. The film was released by British Lion.[2]

| Devil Girl from Mars | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | David MacDonald |

| Produced by | Edward J. Danziger Harry Lee Danziger |

| Written by | James Eastwood John C. Maher |

| Starring | Patricia Laffan Hugh McDermott Adrienne Corri Hazel Court |

| Music by | Edwin Astley |

| Cinematography | Jack Cox |

| Edited by | Peter Taylor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | British Lion Films |

Release date | 2 May 1954 (UK) [1] 27 April 1955 (US) |

Running time | 76 min. |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

The film's storyline concerns a female alien commander sent from Mars to acquire human males to replace their declining male population, thereby saving Martian civilisation from extinction.[3] When negotiation, then intimidation fails, she must use force to obtain co-operation from a remote Scottish village where she has landed her crippled flying saucer.

Plot

Nyah, a female commander from Mars heads for London in her flying saucer. She is part of the advanced alien team looking for Earth men to replace the declining male population on her world, the result of a "devastating war between the sexes". Because of damage to her craft, caused when entering the Earth's atmosphere, and an apparent crash with an airliner, she is forced to land in the remote Scottish moors. She is armed with a raygun that can paralyse or kill, and is accompanied by a tall, menacing robot named Chani.

Professor Arnold Hennessy, an astrophysicist, accompanied by journalist Michael Carter, is sent by the British government to investigate the effects the crash, believed to be caused a meteorite. The pair come to The Bonnie Prince Charlie, a remote inn run by Mr and Mrs Jamieson in the depths of the Scottish Highlands.

At the bar they meet Ellen Prestwick, a fashion model who came to The Bonnie Prince Charlie to escape an affair with a married man. She quickly forms a romantic liaison with Carter. Meanwhile, escaped convict Robert Justin (under the alias Albert Simpson), convicted for accidentally killing his wife, comes to the inn to reunite with barmaid Doris, with whom he is in love.

Nyah happens across the inn, incinerates the Jamieson's handyman David, and enters the bar. When she finds no-one willing to come with her to Mars, she responds with intimidation, trapping the guests and staff within an invisible wall and turning Chani loose to vaporise much of the manor’s grounds. Discovering Justin and Tommy, the Jamieson's young nephew, hiding in the grounds, Nyah kidnaps Tommy as a possible male specimen, and sends Justin back to the inn under some manner of mind control. Nyah then brings Professor Hennessy aboard her spaceship to view the technological achievements of Martian civilisation, including the ship's atomic power source. In exchange for Tommy, Carter volunteers to go to Mars with Nyah.

Realising that the only road to victory over Nyah means trickery, Hennessy suggests Carter sabotage the ship's power source after take off. However Carter attempts a double cross before boarding the ship, snatching Nyah's controller for Chani, but this attempt is thwarted by Nyah's mind control powers. Carter is released by Nyah, and they both return to the bar, where she announces that she will destroy the inn and kill everyone within when she leaves for London. However she allows for one man to go with her in order to escape death. The men draw lots and Carter wins the draw, still hoping to enact Hennessy's plan to destroy the ship.

At the last minute, Justin, alone at the bar and now free from mind control when Nyah returns, offers to go with her of his own free will. After take-off he successfully sabotages Nyah's ship, sacrificing himself to save the men of Earth, and atoning for the death of his wife, and allowing the survivors to celebrate their escape with a drink at the bar.

Cast

- Patricia Laffan as Nyah, the Devil Girl from Mars

- Hugh McDermott as Michael Carter

- Hazel Court as Ellen Prestwick

- Peter Reynolds as Robert Justin/Albert Simpson

- Adrienne Corri as Doris

- Joseph Tomelty as Professor Arnold Hennessey

- John Laurie as Mr. Jamieson

- Sophie Stewart as Mrs. Jamieson

Production

In an interview with Frank J. Dello Stritto, screenwriter John Chartres Mather claimed that Devil Girl from Mars came about while he was working with The Danzigers, who were producing Calling Scotland Yard that appeared as both an American television series and as cinema featurettes in Great Britain and the British Commonwealth. When production finished ahead of schedule, Mather says he was ordered to use up the remaining film studio time already booked and paid for by working on a feature film for the Danzigers.[4]. The interview also claims Patricia Laffan's devil girl costume was economically made by designer John Sutcliffe.

The film was made on a very low budget, with no retakes except in cases where the actual film stock became damaged; it was shot over a period of three weeks, often filming well into the night.[5] Actress Hazel Court later said: "I remember great fun on the set. It was like a repertory company acting that film".[6]

The robot, named Chani, was constructed by Jack Whitehead and was fully automated, although it suffered breakdowns during the filming.[7]

The alien Klaatu, posing as "Mr. Carpenter" in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), was intended by screenwriter Edmund H. North to evoke Jesus Christ,[8] so too are there indications that the Martian woman Nyah was intended to evoke an anti-Virgin Mary image.[9]

Devil Girl from Mars's sound editor was Gerry Anderson (listed as Gerald Anderson in the credits), later to create UK television series such as Thunderbirds.[1] To save time and money, composer Edwin Astley reused his Saber of London score for the film.

Reception

The reviewer for the British Monthly Film Bulletin (1954) writing at the time of the film's release, wrote the "settings, dialogue, characterisation and special effects are of a low order, but even their modest unreality has its charm. There is really no fault in this film that one would like to see eliminated. Everything, in its way, is quite perfect".[10] Devil Girl from Mars developed a following via home video.[11]

Rolling Stone columnist Doug Pratt later called Devil Girl from Mars a "delightfully bad movie". The "acting is really bad and the whole thing is so much fun you want to run to your local community theatre group and have them put it on next, instead of Brigadoon."[12] American film reviewer Leonard Maltin said the film is a "hilariously solemn, high camp British imitation of U. S. cheapies".[13]

In the book Going to Mars the authors described the film as "an undeniably awful but oddly interesting" film. They noted that the plot was "more a reflection of the 1950s view of politics and the era's inequality of the sexes than a thoughtful projection of present or future possibilities".[14]

Eric S. Rabkin likens the character Nyah to a dominatrix and even a neo-Nazi. He said of the film that, "a host of charged images and subconscious fears" are handled with a broad camp irony. Otherwise, "without some underlying psychological engagement, how could anyone sit through a movie so badly made"?[15] The film inspired Hugo and Nebula award-winning author Octavia Butler to begin writing science fiction. After watching the motion picture at age 12, she declared that she could write something better.[16][17] Likewise, the Los Angeles avant-garde artist Gronk lists this film as the crucial factor that guided him in his career choice.[18]

See also

- Mars Needs Women (1967); a gender-reversed version of the same theme

References

- Devil Girl From Mars

- Warren 1982

- Rovin, Jeff (1987). The Encyclopedia of Supervillains. New York: Facts on File. pp. 249–250. ISBN 0-8160-1356-X.

- https://beladraculalugosi.wordpress.com/2015/05/03/vampire-bats-and-devil-girls-from-mars-dracula-producer-john-chartres-mather-interviewed-by-frank-j-dello-stritto/

- Boot 1996, p. 57.

- Weaver 2006, pp. 40–42.

- Johnson 1996, p. 14.

- Weaver 1996, p. 342.

- Miller 2016, p. 158.

- Hunter 1999, p. 62.

- Johnson et al. 2004, p. 38.

- Pratt 2004, p. 332.

- Wilson 2005, p. 95.

- Muirhead et al. 2004, pp. 63–64.

- Rabkin 2005, p. 154.

- Drew 2007, p. 49.

- Butler, Octavia. "Devil Girl From Mars": Why I Write Science Fiction." MIT Communications. Retrieved: January 10, 2015.

- James 2005, p. 66.

Bibliography

- Boot, Andrew. Fragments of Fear: An Illustrated History of British Horror Films. Bangkok, Thailand: Creation Books, 1996. ISBN 1-871592-35-6.

- Drew, Bernard Alger. 100 Most Popular African American Authors: Biographical. Westport Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited, 2007. ISBN 1-59158-322-5.

- Hunter, I. Q. British Science Fiction Cinema. British Popular Cinema. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Psychology Press, 1999. ISBN 0-415-16868-6.

- James, David E. The Most Typical Avant-garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (An Ahmanson Foundation book in the Humanities). Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2005. ISBN 0-520-24257-2.

- Johnson, John. Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup, and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1996. ISBN 0-7864-0093-5.

- Johnson, Tom, Mark A. Miller and Jimmy Sangster. The Christopher Lee Filmography: All Theatrical Releases, 1948-2003. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2004. ISBN 0-7864-1277-1.

- Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- Muirhead, Brian, Judith and Garfield Reeves-Stevens. Going to Mars: The Stories of the People Behind NASA's Mars Missions Past, Present, and Future. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004. ISBN 0-671-02796-4.

- Pratt, Douglas F. Doug Pratt's DVD: Movies, Television, Music, Art, Adult, and More!, Volume 1. Sag Harbor, New York: Harbor Electronic Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-932916-00-8.

- Rabkin, Eric S. Mars: A Tour of the Human Imagination. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. ISBN 0-275-98719-1.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies, American Science Fiction Movies of the 50s, (Vol I: 1950 - 1957). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Weaver, Tom. It Came from Weaver Five: Interviews With 20 Zany, Glib and Earnest Moviemakers in the Sf and Horror Traditions of the Thirties, Forties, Fifties and Sixties. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1996, ASIN: B000MBQROA.

- Weaver, Tom. Science Fiction Stars and Horror Heroes: Interviews with Actors, Directors, Producers and Writers of the 1940s Through 1960s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2006, ISBN 0-7864-2857-0.

- Wilson, John. The Official Razzie Movie Guide: Enjoying the Best of Hollywood's Worst. New York: Hachette Digital, Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-446-69334-0.