Derveni papyrus

The Derveni papyrus is an ancient Macedonian papyrus roll that was found in 1962. It is a philosophical treatise that is an allegorical commentary on an Orphic poem, a theogony concerning the birth of the gods, produced in the circle of the philosopher Anaxagoras. It was composed near the end of the 5th century BC,[1] and "in the fields of Greek religion, the sophistic movement, early philosophy, and the origins of literary criticism it is unquestionably the most important textual discovery of the 20th century."[2] The roll itself dates to around 340 BC, during the reign of Philip II of Macedon, making it Europe's oldest surviving manuscript.[3][4] While interim editions and translations were published over the subsequent years, the manuscript as a whole was finally published in 2006.

| Derveni papyrus | |

|---|---|

| Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki | |

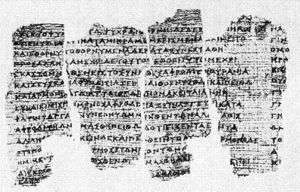

Some fragments of the Derveni papyrus | |

| Type | Papyrus roll |

| Date | 340 BC, from an end 5th century BC original |

| Place of origin | Macedon |

| Language(s) | Ancient Greek, mixed dialects |

| Material | Papyrus |

| Size | 266 fragments |

| Format | 26 columns |

| Condition | Fragmentary, charred from funeral pyre |

| Contents | Commentary on a hexameter poem ascribed to Orpheus |

| Discovered | 1962 |

Discovery

The roll was found on 15 January 1962 at a site in Derveni, Macedonia, northern Greece, on the road from Thessaloniki to Kavala. The site is a nobleman's grave in a necropolis that was part of a rich cemetery belonging to the ancient city of Lete.[5] It is the oldest surviving manuscript in the Western tradition and the only known ancient papyrus found in Greece proper. It might in fact be the oldest surviving papyrus written in Greek regardless of provenance.[1][3] The archaeologists Petros Themelis and Maria Siganidou recovered the top parts of the charred papyrus scroll and fragments from ashes atop the slabs of the tomb; the bottom parts had burned away in the funeral pyre. The scroll was carefully unrolled and the fragments joined together, thus forming 26 columns of text.[1] It survived in the humid Greek soil, which is unfavorable to the conservation of papyri, because it was carbonized (hence dried) in the nobleman's funeral pyre.[6] However, this has made it extremely difficult to read, since the ink is black and the background is black too; in addition, it survives in the form of 266 fragments, which are conserved under glass in descending order of size, and has had to be painstakingly reconstructed. Many smaller fragments are still not placed. The papyrus is kept in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki.

Content

The main part of the text is a commentary on a hexameter poem ascribed to Orpheus, which was used in the mystery cult of Dionysus by the 'Orphic initiators'. Fragments of the poem are quoted, followed by interpretations by the main author of the text, who tries to show that the poem does not mean what it literally says. The poem begins with the words "Close the doors, you uninitiated", a famous admonition to secrecy, also quoted by Plato. The interpreter claims that this shows that Orpheus wrote his poem as an allegory. The theogony described in the poem has Nyx (Night) give birth to Heaven (Uranus), who becomes the first king. Cronus follows and takes the kingship from Uranus, but he is likewise succeeded by Zeus, whose power over the whole universe is celebrated. Zeus gains his power by hearing oracles from the sanctuary of Night, who tells him "all the oracles which afterwards he was to put into effect."[7] At the end of the text Zeus rapes his mother Rhea, which, in the Orphic theogony, will lead to the birth of Demeter. Zeus would then have raped Demeter, who would then have given birth of Persephone, who then married Dionysus. However, this part of the story must have continued in a second roll which is now lost.

The interpreter of the poem argues that Orpheus did not intend any of these stories in a literal sense, but they are allegorical in nature.

This poem is strange and riddling to people, though [Orpheus] did not intend to tell contentious riddles but rather great things in riddles. In fact he is speaking mystically, and from the very first word all the way to the last. As he also makes clear in the well recognized verse: for, having ordered them to "put doors to their ears," he says that he is not legislating for the many [but addressing himself to those] who are pure in hearing … and in the following verse …[8]

The first surviving columns of the text are less well preserved, but talk about occult ritual practices, including sacrifices to the Erinyes (Furies), how to remove daimones that become a problem, and the beliefs of the magi. They include a quotation of the philosopher Heraclitus. Their reconstruction is extremely controversial, since even the order of fragments is disputed. Two different reconstructions have recently been offered, that by Valeria Piano[9][10] and that by Richard Janko, who says that he has found that these columns also include a quotation of the philosopher Parmenides.[11]

Recent reading

The text was not officially published for forty-four years after its discovery (though three partial editions were published). A team of experts was assembled in autumn 2005 led by A. L. Pierris of the Institute for Philosophical studies and Dirk Obbink, director of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri project at the University of Oxford, with the help of modern multispectral imaging techniques by Roger Macfarlane and Gene Ware of Brigham Young University to attempt a better approach to the edition of a difficult text. However, nothing appears to have been published as a result of that initiative, and the photographs are not available to scholars or the Museum. Meanwhile, the papyrus was finally published by a team of scholars from Thessaloniki (Tsantsanoglou et al., below), which provides a complete text of the papyrus based on autopsy of the fragments, with photographs and translation. More work clearly remained to be done (see Janko 2006, below). Subsequent progress has been made in reading the papyrus by Valeria Piano[9] and Richard Janko,[11] who has developed a new method for taking digital microphotographs of the papyrus, which permits some of its most difficult passages to be read for the first time.[12] Examples of these images are now published.[11] A version of Janko's new text is available in the recent edition by Mirjam Kotwick, and a new edition in English is in preparation.[13] A complete digital edition of the papyrus using the new technique is a major desideratum.

Style of writing

The text of the papyrus contains a mix of dialects. It is mainly a mixture of Attic and Ionic Greek; however it contains a few Doric forms. Sometimes the same word appears in different dialectal forms e.g. cμικρό-, μικρό; ὄντα, ἐόντα; νιν for μιν etc.[14]

Oldest 'book' of Europe – UNESCO Memory of The World Register

On 12 December 2015, the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki held the official event to celebrate the registration of the Derveni Papyrus in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

According to UNESCO

"The Derveni Papyrus is of immense importance not only for the study of Greek religion and philosophy, which is the basis for the western philosophical thought, but also because it serves as a proof of the early dating of the Orphic poems offering a distinctive version of Presocratic philosophers. The text of the Papyrus, which is the first book of western tradition, has a global significance, since it reflects universal human values: the need to explain the world, the desire to belong to a human society with known rules and the agony to confront the end of life."[15]

References

- "The Derveni Papyrus: An Interdisciplinary Research Project". Harvard University, Center for Hellenic Studies.

- Richard Janko, "The Derveni Papyrus: An Interim Text", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 141 (2002), p. 1

- "Ancient scroll may yield religious secrets". Associated Press. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- "THE PAPYRUS OF DERVENI". Hellenic Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 28 April 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- Betegh, Gábor (19 November 2007). The Derveni Papyrus: Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-521-04739-5. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- Betegh, Gábor (2004). The Derveni Papyrus: Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780521801089.

- Bowersock, G. W. Tangled Roots. From The New Republic Online 8 June 2005. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- Bierl, Anton (2014). 'Riddles over Riddles': 'Mysterious' and 'Symbolic' (Inter)textual Strategies. The Problem of Language in the Derveni Papyrus. 978-0-674-72676-5: University of Basel.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Piano, Valeria (2016). "P.Derveni III-VI: una reconsiderazione del testo". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 197: 5–16.

- Piano, Valeria (2016). Il Papiro di Derveni tra religione e filosofia. Florence: Leo S. Olschki. ISBN 978-88-222-6477-0.

- Janko, Richard (2016). "Parmenides in the Derveni Papyrus". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 200: 3–23.

- "New readings in the Derveni Papyrus". Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- "Nine Teams of Scholars Awarded 2016 ACLS Collaborative Research Fellowships". Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- For a full list, see Janko (1997) 62–3

- "The Derveni Papyrus: The oldest 'book' of Europe | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

Further reading

- A. Bernabé, "The Derveni theogony: many questions and some answers", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 103, 2007, 99-133.

- Gábor Betegh, 2004. The Derveni Papyrus: Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation (Cambridge University Press). A preliminary reading, critical edition and translation. ISBN 0-521-80108-7. ()

- Richard Janko's Review of Betegh 2004

- Richard Janko. "The Physicist as Hierophant: Aristophanes, Socrates and the Authorship of the Derveni Papyrus," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 118, 1997, pp. 61–94.

- R. Janko, "The Derveni Papyrus (Diagoras of Melos, Apopyrgizontes Logoi?): a New Translation," Classical Philology 96, 2001, pp. 1–32 .

- R. Janko, "The Derveni Papyrus: An Interim Text," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 141, 2002, pp. 1–62.

- A. Laks, "Between Religion and Philosophy: The Function of Allegory in the Derveni Papyrus", Phronesis 42, 1997, pp. 121–142.

- A. Laks, G.W. Most (editors), 1997. Studies on the Derveni Papyrus (Oxford University Press). (books.google.)

- G.W. Most, "The Fire Next Time. Cosmology, Allegories, and Salvation in the Derveni Papyrus", Journal of Hellenic Studies 117, 1997, pp. 117–135.

- Io. Papadopoulou and L. Muellner (editors), Washington D.C. 2014. Poetry as Initiation: The Center for Hellenic Studies Symposium on the Derveni Papyrus (Hellenic Studies Series).

- K. Tsantsanoglou, G.M. Parássoglou, T. Kouremenos (editors), 2006. The Derveni Papyrus (Leo. S. Olschki Editore, Florence [series Studi e testi per il Corpus dei papiri filosofici greci e latini, vol. 13]). ISBN 88-222-5567-4.

- V. Piano (editor), 2016. Il Papiro di Derveni tra religione e filosofia (Leo. S. Olschki Editore, Florence [series Studi e testi per il Corpus dei papiri filosofici greci e latini, vol. 18]). ISBN 88-222-6477-0.

- V. Piano, "P.Derveni III-VI: una riconsiderazione del testo", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 197, 2016, pp. 5–16.

- Richard Janko's Review of Tsantsanoglou, Parássoglou, & Kouremenos 2006;Tsantsanoglou, Parássoglou, & Kouremenos' Response to Janko; Janko's Response.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Derveni papyrus. |

- "The Derveni Papyrus - A conversation with Richard Janko", Ideas Roadshow, 2013