Anaxagoras

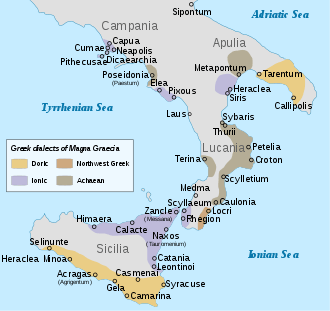

Anaxagoras (/ˌænækˈsæɡərəs/; Greek: Ἀναξαγόρας, Anaxagoras, "lord of the assembly"; c. 510 – c. 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. According to Diogenes Laërtius and Plutarch, in later life he was charged with impiety and went into exile in Lampsacus; the charges may have been political, owing to his association with Pericles, if they were not fabricated by later ancient biographers.[2]

Anaxagoras | |

|---|---|

Anaxagoras; part of a fresco in the portico of the National University of Athens. | |

| Born | c. 510 BC |

| Died | c. 428 BC |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Pluralist school |

Main interests | Natural philosophy |

Notable ideas | Cosmic Mind (Nous) ordering all things The Milky Way (Via Lactea) as a concentration of distant stars[1] |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Responding to the claims of Parmenides on the impossibility of change, Anaxagoras described the world as a mixture of primary imperishable ingredients, where material variation was never caused by an absolute presence of a particular ingredient, but rather by its relative preponderance over the other ingredients; in his words, "each one is... most manifestly those things of which there are the most in it".[3] He introduced the concept of Nous (Cosmic Mind) as an ordering force, which moved and separated out the original mixture, which was homogeneous, or nearly so.

He also gave a number of novel scientific accounts of natural phenomena. He deduced a correct explanation for eclipses and described the Sun as a fiery mass larger than the Peloponnese, as well as attempting to explain rainbows and meteors.

Biography

Anaxagoras is believed to have enjoyed some wealth and political influence in his native town of Clazomenae. However, he supposedly surrendered this out of a fear that they would hinder his search for knowledge.[4] The Roman author Valerius Maximus preserves a different tradition: Anaxagoras, coming home from a long voyage, found his property in ruin, and said: "If this had not perished, I would have"—a sentence described by Valerius as being "possessed of sought-after wisdom!"[5][6]

Anaxagoras was a Greek citizen of the Persian Empire and had served in the Persian army; he may have been a member of the Persian regiments that entered mainland Greece during the Greco-Persian Wars.[7] Though this remains uncertain, "it would certainly explain why he came to Athens in the year of Salamis, 480/79 B.C."[7] Anaxagoras is said to have remained in Athens for thirty years. Pericles learned to love and admire him, and the poet Euripides derived from him an enthusiasm for science and humanity.[4]

Anaxagoras brought philosophy and the spirit of scientific inquiry from Ionia to Athens. His observations of the celestial bodies and the fall of meteorites led him to form new theories of the universal order, and to prediction of the impact of meteorites. Plutarch[8] says "Anaxagoras is said to have predicted that if the heavenly bodies should be loosened by some slip or shake, one of them might be torn away, and might plunge and fall down to earth". According to Pliny [9] he was credited with predicting the fall of the meteorite in 467.[10] He attempted to give a scientific account of eclipses, meteors, rainbows, and the Sun, which he described as a mass of blazing metal, larger than the Peloponnese; his theories about eclipses, the Sun and Moon may well have been based on observations of the eclipse of 463 BCE, which was visible in Greece.[11] He was the first to explain that the Moon shines due to reflected light from the Sun. He also said that the Moon had mountains and believed that it was inhabited. The heavenly bodies, he asserted, were masses of stone torn from the Earth and ignited by rapid rotation.[4] He was the first to give a correct explanation of eclipses, and was both famous and notorious for his scientific theories, including the claims that the Sun is a mass of red-hot metal, that the Moon is earthy, and that the stars are fiery stones.[12] He thought the Earth was flat and floated supported by 'strong' air under it and disturbances in this air sometimes caused earthquakes.[13] These speculations made him vulnerable in Athens to a charge of impiety. Diogenes Laërtius reports the story that he was prosecuted by Cleon for impiety, but Plutarch says that Pericles sent his former tutor, Anaxagoras, to Lampsacus for his own safety after the Athenians began to blame him for the Peloponnesian war.[14]

The charges against Anaxagoras may have stemmed from his denial of the existence of a solar or lunar deity.[15] According to Laërtius, Pericles spoke in defense of Anaxagoras at his trial, c. 450.[16] Even so, Anaxagoras was forced to retire from Athens to Lampsacus in Troad (c. 434 – 433). He died there in around the year 428. Citizens of Lampsacus erected an altar to Mind and Truth in his memory, and observed the anniversary of his death for many years. They placed over his grave the following inscription: Here Anaxagoras, who in his quest of truth scaled heaven itself, is laid to rest.[lower-alpha 1]

Anaxagoras wrote a book of philosophy, but only fragments of the first part of this have survived, through preservation in work of Simplicius of Cilicia in the 6th century AD.

Philosophy

According to Anaxagoras all things have existed in some way from the beginning, but originally they existed in infinitesimally small fragments of themselves, endless in number and inextricably combined throughout the universe. All things existed in this mass, but in a confused and indistinguishable form.[4] There was an infinite number of homogeneous parts (ὁμοιομερῆ) as well as heterogeneous ones.[18]

The work of arrangement, the segregation of like from unlike and the summation of the whole into totals of the same name, was the work of Mind or Reason (νοῦς). Mind is no less unlimited than the chaotic mass, but it stood pure and independent, a thing of finer texture, alike in all its manifestations and everywhere the same. This subtle agent, possessed of all knowledge and power, is especially seen ruling in all the forms of life.[19] Its first appearance, and the only manifestation of it which Anaxagoras describes, is Motion. It gave distinctness and reality to the aggregates of like parts.[4]

Decrease and growth represent a new aggregation (σὐγκρισις) and disruption (διάκρισις). However, the original intermixture of things is never wholly overcome.[4] Each thing contains in itself parts of other things or heterogeneous elements, and is what it is, only on account of the preponderance of certain homogeneous parts which constitute its character.[18] Out of this process arise the things we see in this world.[18]

Literary references

Anaxagoras is mentioned by Socrates during his trial in Plato's "Apology". In the Phaedo, Plato portrays Socrates saying of Anaxagoras that as a young man: 'I eagerly acquired his books and read them as quickly as I could'.[20]

In a quote which begins Nathanael West's first book The Dream Life of Balso Snell (1931), Marcel Proust's character Bergotte says, "After all, my dear fellow, life, Anaxagoras has said, is a journey."

Anaxagoras appears as a character in Faust, Part II by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Anaxagoras appears as a character in The Ionia Sanction, by Gary Corby.

Anaxagoras is referred to and admired by Cyrus Spitama, the hero and narrator of Creation, by Gore Vidal. The book contains this passage, explaining how Anaxagoras became influential:

- [According to Anaxagoras] One of the largest things is a hot stone that we call the sun. When Anaxagoras was very young, he predicted that sooner or later a piece of the sun would break off and fall to earth. Twenty years ago, he was proved right. The whole world saw a fragment of the sun fall in a fiery arc through the sky, landing near Aegospotami in Thrace. When the fiery fragment cooled, it proved to be nothing more than a chunk of brown rock. Overnight Anaxagoras was famous. Today his book is read everywhere. You can buy a secondhand copy in the Agora for a drachma.[21]

William H. Gass begins his novel, The Tunnel (1995), with a quote from Anaxagoras: "The descent to hell is the same from every place."

He is also mentioned in Seneca's Natural Questions (Book 4B, originally Book 3: On Clouds, Hail, Snow) It reads: "Why should I too allow myself the same liberty as Anaxagoras allowed himself?"

Dante Alighieri places Anaxagoras in the First Circle of Hell (Limbo) in his Divine Comedy (Inferno, Canto IV, line 118).

Chapter 5 in Book II of De Docta Ignorantia (1440) by Nicholas of Cusa is dedicated to the truth of the sentence "Each thing is in each thing" which he attributes to Anaxagoras.

See also

- Anaxagoras (crater) on the Moon

- Squaring the circle

References

Footnotes

- Ancient Greek: ἐνθάδε, πλεῖστον ἀληθείας ἐπὶ τέρμα περήσας οὐρανίου κόσμου, κεῖται Ἀναξαγόρας.[17]

Citations

- DK 59 A80: Aristotle, Meteorologica 342b.

- Filonik, Jakub (2013). "Athenian impiety trials: a reappraisal". Dike (16): 26–33. doi:10.13130/1128-8221/4290.

- Anaxagoras (2011-03-11). "Anaxagoras of Clazomenae". In Curd, Patricia (ed.). A Presocratics Reader. Hackett. ISBN 978-1-60384-305-8.

B12

- Wallace, William; Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 943.

- Anaxagoras of Clazomenae: Fragments and Testimonia : a text and translation with notes and essays. University of Toronto Press. 2007. ISBN 9780802093257.

- Val. Max., VIII, 7, ext., 5: Qui, cum e diutina peregrinatione patriam repetisset possessionesque desertas vidisset, "non essem – inquit "ego salvus, nisi istae perissent." Vocem petitae sapientiae compotem!

- Copleston 2003, p. 66.

- Life of Lysander 12.1

- Natural History 2.149

- Couprie, Dirk (2004). "How Thales Was Able to "Predict" a Solar Eclipse Without the Help of Alleged Mesopotamian Wisdom". Early Science and Medicine. 9 (4): 321–337. doi:10.1163/1573382043004631. ISSN 1383-7427.

- "NASA - Total Solar Eclipse of -462 April 30".

- Anaxagoras biography

- Burnet, John (2003). Early Greek Philosophy 1892. Kessinger. ISBN 978-0-7661-2826-2.

- Plutarch, Pericles

- Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 145.

- Taylor, A.E. (1917). "On the date of the trial of Anaxagoras". Classical Quarterly. 11 (2): 81–87. doi:10.1017/s0009838800013094.

- Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers, § 2.15

-

- Diels, Hermann, ed. (1912). Die fragmente der Vorsokratiker griechisch und deutsch. Berlin, Weidmannsche buchhandlung.

B12

- Plato, Phaedo, 85b

- Vidal, Gore, Creation: restored edition, chapter 2, Vintage Books (2002)

Sources

- Copleston, Frederick Charles (2003). "IX: The Advance of Anaxagoras". A History of Philosophy: Volume 1 Greece and Rome (reprint). Continuum. ISBN 978-0826468956.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

Editions of the fragments

- Curd, Patricia (ed.), Anaxagoras of Clazomenae. Fragments and Testimonia: A Text and Translation with Notes and Essays, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007.

- Sider, David (ed.), The Fragments of Anaxagoras, with introduction, text, and commentary, Sankt Augustin: Academia Verlag, 2005.

- Kirk G. S.; Raven, J. E. and Schofield, M. (1983) The Presocratic Philosophers: a critical history with a selection of texts (2nd ed.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0-521-25444-2; originally authored by Kirk and Raven and published in 1957 OCLC 870519

Studies

- Bakalis Nikolaos (2005). Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing, Victoria, BC., ISBN 1-4120-4843-5

- Barnes J. (1979). The Presocratic Philosophers, Routledge, London, ISBN 0-7100-8860-4, and editions of 1982, 1996 and 2006

- Burnet J. (1892). Early Greek Philosophy A. & C. Black, London, OCLC 4365382, and subsequent editions, 2003 edition published by Kessinger, Whitefish, Montana, ISBN 0-7661-2826-1

- Cleve, Felix M. (1949). The Philosophy of Anaxagoras: An attempt at reconstruction King's Crown Press, New York OCLC 2692674; republished in 1973 by Nijhoff, The Hague, as The Philosophy of Anaxagoras: As reconstructed ISBN 90-247-1573-3

- Davison, J. A. (1953). "Protagoras, Democtitus, and Anaxagoras". Classical Quarterly. 3 (n.s) (1–2): 33–45. doi:10.1017/s0009838800002585.

- Filonik, Jakub. (2013). "Athenian impiety trials: a reappraisal". Dike: rivista di storia del diritto greco ed ellenistico 16. doi:10.13130/1128-8221/4290

- Gershenson, Daniel E. and Greenberg, Daniel A. (1964) Anaxagoras and the birth of physics, Blaisdell Publishing Co., New York, OCLC 899834

- Graham, Daniel W. (1999). "Empedocles and Anaxagoras: Responses to Parmenides" Chapter 8 of Long, A. A. (1999) The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 159–180, ISBN 0-521-44667-8

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1965). "The Presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus" volume 2 of A History of Greek Philosophy Cambridge University Press, Cambridge OCLC 4679552; 1978 edition ISBN 0-521-29421-5

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1962). A History of Greek Philosophy. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Luchte, James (2011). Early Greek Thought: Before the Dawn. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567353313.

- Mansfield, J. (1980). "The Chronology of Anaxagoras' Athenian Period and the Date of His Trial". Mnemosyne. 33 (1–2): 17–95. doi:10.1163/156852580X00271.

- Sandywell, Barry (1996). Presocratic Reflexivity: The Construction of Philosophical Discourse, c. 600–450 BC. 3. London: Routledge.

- Schofield, Malcolm (1980). An Essay on Anaxagoras. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, A.E. (1917). "On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras". Classical Quarterly. 11 (2): 81–87. doi:10.1017/S0009838800013094. Zenodo: 1428584.

- Taylor, C. C. W. (ed.) (1997). Routledge History of Philosophy: From the Beginning to Plato, Vol. I, pp. 192–225, ISBN 0-415-06272-1

- Teodorsson, Sven-Tage (1982). Anaxagoras' Theory of Matter. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Göteborg, Sweden, ISBN 91-7346-111-3

- Torrijos-Castrillejo, David (2014) Anaxágoras y su recepción en Aristóteles. Romae: EDUSC, ISBN 978-88-8333-325-5 (in Spanish)

- Wright, M.R. (1995). Cosmology in Antiquity. London: Routledge.

- Zeller, A. (1881). A History of Greek Philosophy: From the Earliest Period to the Time of Socrates, Vol. II, translated by S. F. Alleyne, pp. 321–394

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anaxagoras. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anaxagoras |

- Curd, Patricia. "Anaxagoras". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Anaxagoras entry by Michael Patzia in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Anaxagoras", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Translation and Commentary from John Burnet's Early Greek Philosophy.

- Anaxagoras: Fragments from Early Greek Philosophy by John Burnet, 3rd edition (1920).

- Works by or about Anaxagoras at Internet Archive

- Works by Anaxagoras at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)