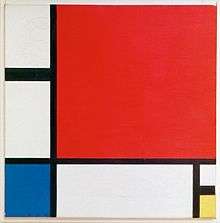

Composition with Red Blue and Yellow

Composition II with Red Blue and Yellow is a 1930 painting by Piet Mondrian. A well-known work of art, Mondrian contributes to the abstract visual language in a large way despite using a relatively small canvas. Thick, black brushwork defines the borders of the different geometric figures. Comparably, the black brushwork on the canvas is minimal but it is masterfully applied to become one of the defining features of the work.

| Composition with Red Blue and Yellow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Piet Mondrian |

| Year | 1929 |

| Type | Oil and paper on canvas |

| Dimensions | 59,5 cm × 59,5 cm (23.4 in × 23.4 in) |

| Location | National Museum, Belgrade, Serbia[1] |

Mondrian's origins and connection with De Stijl

Composition II with Red Blue and Yellow is a product of the Dutch De Stijl movement, which translates to “The Style”.[2] The De Stijl foundation can be viewed as an overlapping of individual theoretical and artistic pursuits. Mondrian is widely seen as the prominent artist for the movement and is thus held responsible for bringing popularity to the rather obscure style.[3] Born in the Netherlands in 1872, Mondrian is cited as always having an interest in art. This transformed from a hobby to a passion when his uncle, Fritz Mondrian (a professional painter), helped him move to Amsterdam where he studied for three years at the Academy of Fine Arts under the master August Allebé.[3] When he moved to Paris in 1910, Mondrian began to discover his potential.[3] It was in Paris that he was introduced to Cubism, a major influence to his work. He is quoted as having said “of all the abstraction artists, I felt only the Cubists had found the right path.” .[3] He still found this style too naturalistic however, and began to dive even deeper into abstraction. A short visit back to the Netherlands led to an extended stay for five years due to the outbreak of World War 1 (1914).[3] Although an unexpected turn of events, Mondrian made many important connections during this time that led to establishment of De Stijl. An encounter with fellow Dutch artist Bart van der Leck provided ground for Mondrian to exchange ideas. From van der Leck he received the concept of painting flat areas of pure color; a solution to Mondrian's problem of coloring – he was then using color in what he considered an Impressionist way, which was too restless and emotional. In return, van der Leck adopted Mondrian's concept of crossed vertical and horizontal lines as a basis for composition.[3] These two technical elements are consistent throughout all of Mondrian's work. Shortly after the formation of Mondrian and van der Leck's working relationship, they were contacted by Theo van Doesburg, a painter who frequently wrote about art for different periodicals and who is considered the propagandist of the De Stijl movement. He invited Mondrian and van der Leck to join his initiative to start an artistic review periodical. They agreed and the result of this was the journal entitled De Stijl.[3]

De Stijl

Together they formed an artistic collective that consisted not only of painters but also architects; the movement was confined to strictly Dutch areas due to war. These artists cannot be considered the same. For example, not all De Stijl artists produced work that mimicked Mondrian. It was more a group of individual artists/architects who applied similar and distinct techniques to their work in hopes of achieving a similar, theoretical goal. Mondrian attempts to define the ambition of De Stijl artists in his personal artistic manifesto, Neo-Plasticist in Painting (1917). To create the essence of life itself through abstraction, which relies on what he refers to as the universal means of expression: straight lines and primary colors. [4] This essence of life can be illustrated by transcending the particular to express the universal. Mondrian claimed the particular to be associated with a Romantic, subjective appeal. Thus, the universal must be something that goes beyond the[4] surface of nature. Mondrian's art also had a clear spiritual quality to it. He practiced Theosophy, a self-styled universal religion rooted in mystic, oriental interpretation that promoted opposites as a form of unity.[5] Theosophical philosophy informing Mondrian's art is evidence of their shared terminology. Nieuwe Beelding, a word used in Theosophical teachings, makes an appearance in Mondrian's work in a major way: as an alternative title to De Stijl, Nieuwe Beelding translates to Neo-Plasticism, a term used in Mondrian's personal essays to describe his art.

Individual efforts

Examining Composition with Red Blue and Yellow, Mondrian's De Stijl practices are in full effect. The contrasting horizontal and vertical lines represent to Mondrian an active relationship in which he intended to mimic the rhythm and vibrations of life that transcends symbolic knowledge. The reduced colours of red blue and yellow and accentuated thick, black lines that cross over each other are similarly rendered. His depiction of inner reality (essence of life), is believed to be found through the interplay of contrasting pictorial elements.[3] It is arguable that all elements found within Composition are contrasting and thus indicative of the inner harmony of life that lies beneath the surface. Mondrian theories do not accumulate in Composition; he did not even consider this is a success. He called it “static.” [3] He continued to progress and refine his work, and it is in his final pieces of work before his death (1944) that he achieves some satisfaction. Despite De Stijl being a movement confined to Dutch regions, many credit the movement, and specifically Mondrian, as having played a major role in articulating the abstract landscape and defining the current terms for the art world today.

References

- "Foreign Art Collection". The National Museum in Belgrade.

- "de Stijl". the-artists.org. December 28, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- Sweeny, James Johnson (Spring 1945). "Piet Mondrian". The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art. 12.

- Blotkamp, C. (2001). Mondrian: The Art of Destruction. Reaktion Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-86189-100-6. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- Fingesten, Peter (1961). "Spirituality, Mysticism and Non-Objective Art". Art Journal. 21 (1): 2–6. doi:10.2307/774289. ISSN 0004-3249. JSTOR 774289.