Compassion fade

Compassion fade is the tendency to experience a decrease in empathy as the number of people in need of aid increase.[1] It is a type of cognitive bias that has a significant effect on the prosocial behaviour that generates helping.[2] The psychological theory may be observed by an individual’s reluctance to help when faced with mass crises. The term was developed by psychologist and researcher Paul Slovic.[3]

The most common explanation for compassion fade is humans use of a mental shortcut called the affect heuristic. The affect heuristic causes people to make decisions based off emotional attachments to a stimulus.[4] While in the past there has been a view that humans make decisions in line with the expected utility theory, current theories suggest we make decisions via two different thinking mechanisms outlined in the dual process theory. Compassion fade is an irrational phenomenon which is carried out through system 1 thinking mechanisms. System 1 is characterised by fast, automatic, effortless, associative thinking patterns and is often driven by emotions, unlike system 2 which is a more effortful, slower process whereby initial thoughts are challenged against other known knowledge leading to rational and considered decisions.[5] It is this emotional element of system 1 that leads us to see the effects of compassion fade, as we make decisions based upon the affect and feelings of emotion over the facts of the situation.

A response to the victim size is determined by the balancing of self-interest and the concern for others. Within the confirmation bias theory, people tend to consider self-interest alongside concern for others. The emotional response results in the individual’s willingness and ability to help. An apathetic response following a large number of victims is considered to be normal because people have a limited capacity to feel sympathy. Explanations for compassion fade include: the affective bias theory (empathy is greatest when one is able to visualise a victim) and the motivated choice theory (when people suppress feelings to avoid being emotionally overwhelmed).[6] Other cognitive biases that contribute to compassion fade include: The Identifiable victim effect (IVE), Pseudo-inefficacy and the Prominence effect. These effects show how compassion fade is an irrational thought process driven by how much emotion we feel for a certain cause. By understanding these effects they can be used by charities to help maximise donations by understanding the thought process behind why people donate.[1][7]

Compassion fade has also been used to refer to “the arithmetic of compassion”, “compassion collapse” and “psychic numbing”.[8]

Definition

Compassion fade, coined by psychologist Paul Slovic, is the tendency of people to experience a decrease in empathy as the number of people in need of aid increase.[3][9] Compassion fade is an example of a cognitive bias that explains the tendency to ignore unwanted information when making a decision, so it is easier to justify. The theory refers to compassion as compassionate behaviour, that is the intention to help or the act of helping.[8]

Compassion fade can be explained by the cognitive processes that lead to helping. First is the individual’s response to victim group, followed by motivation to help which therefore generates the intention or act of helping. A conceptual model of helping highlights the self-concern and concern for others as mediators of motivation. Within the compassion fade theory, people tend to be influenced by:[6][8]

- The anticipated positive effect (self-concern)

- Empathic concern (concern for others)

- The perceived impact (hybrid of both interests)

Context

The concept of compassion fade was introduced in 1947 by Joseph Stalin’s statement “the death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic”.[9]

Traditional economic and psychological theory of choice is based on the assumption that preferences are determined by the objective valuation of an item. Research in the 1960s and 70s by psychologists Paul Slovic and Sarah Litchfield, first looked at the emotional mechanisms in risk-assessment and developed the theory of preference construction, people tend to unequally weigh possible alternatives when making a decision.[3][10]

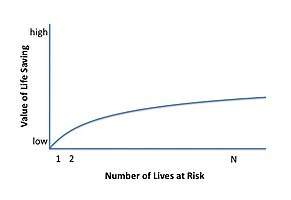

The term “psychic numbing” was coined in 1997 to describe the non-linear relationship between provision of aid and the number of lives at risk.[11] It explains how valuation of lives are cognitively perceived: each life decreases in marginal value as the number of victims increase. In the early 2000s, research by behavioural economist Daniel Kahnerman found people have different emotional and cognitive reactions to numerical information. Similar research by Slovic in 2007 demonstrated people’s emotional responses decreased as the number of lives increase which led to the development of Compassion fade.[9][10]

Measurements

Valuation as a function of victim numbers

Compassion fade contradicts the traditional model for valuing life that assumes all lives should be valued equally. Empirical data on charitable giving found that donations are not linearly related to the number of victims but rather decrease as the number of victims increase. This concept termed "psychophysical" or “psychic numbing”.[11] A psychophysical numbing function depicts the number of lives at risk as a function of the value of life saving. In accordance to the theory of compassion fade, the function illustrates a decreasing marginal increase as the number of lives at risk increase. For example, when a one life is at risk the value is $100, when ten lives are at risk the value decreases to $80 and when fifty lives are at risk the value decreases to $50. Compassion fade explains this as people’s perception that as the number of lives in need of aid increases, individuality decreases and thus the value of the life decreases.[10]

Effects of compassion fade on the valuation of victim numbers is seen through the singularity effect. Research showed as more information about the group size is provided, it more negatively effects the valuation of lives.[12]

Other studies that investigated compassion fade with smaller victim numbers were not effective when using this prototype because it is not difficult to picture comprehensive images of victims with smaller number increases.[6][10]

Valuation as a function of human lives

Compassion fade can be conceptually measured with the number of lives as a function of emotional response. The traditional model for valuing human lives would assume emotional reactions and the number of lives are positively correlated. However, research found people do not have the same cognitive and emotional response to the number of victims in need. The increasing marginal decrease in emotional response to the number of lives at risk is the foundation for the theory of Compassion Fade.

Research by Paul Slovic found the loss of a single identifiable appears elicits a greater emotional response where as people grow apathetic as the number of lives at risk increase because it is too emotionally distressing to comprehend. Similar research suggests that compassion fade occurs as soon as the number of victims increases from one.

The negative relationship between emotional response and valuation of human lives explains why life is not valued equally. It conceptually explains why compassion fade fails to initiate emotional processes that lead to helping behaviour. Effects of this relationship can be seen through The Singularity Effect and Pseudo-inefficacy.[10]

Causes

Mental imagery and attention explanation

Compassion is experienced greatest when an individual is able to pay more attention to and more vividly picture a victim. Psychological research into choice theory found that vivid mental stimuli plays a large part in processing information. Given the human ability to feel compassion is limited, more vivid mental images are closely related to greater empathy. Single, individual victims tend to be easier to mentally depict in greater detail. A large number of victims is more difficult to picture so it becomes more depersonalised causing the individual to feel apathetic and empathy to stretch thin.[13]

Studies on cognitive biases categorise this tendency as a ‘heuristic’ to explain that people make decisions based on how easily the information is to process. It is easier to process information about a single target (i.e. one victim) versus an abstract target (i.e. multiple victims) that in effect loses the emotional meaning attached to it.[2]

Similar studies have demonstrated when an individual is presented with a number of single victims in a group they tend to experience less empathetic concern towards any member. To recognise each victim individually a person must focus specifically on individual features. If the individual is unable to develop a cohesive image of these features, these images will not generate compassionate behaviour.

Information processing explanation

Compassion fade can be considered an attempt to moderate one’s emotions when faced with mass crises.3 Research supports that individuals tune out to feelings to avoid becoming emotionally overwhelmed or distressed. An experiment conducted by Vastfjall and Slovic in 2014 found people who did not regulate emotions experienced a decreased effect of compassion fade.[13]

Similar research on charitable showed individuals that individuals that were able to more effectively process information experienced stronger emotional responses which led to higher donations.[10]

Individual differences

Compassion fade is greatly influenced by individual factors responsible in the cognitive mechanisms that effect emotional responses. Compassion fade was believed to be correlated with intelligence; however, studies have shown numerical literacy and ability to think rationally were is more influential on the individual’s empathetic concern.[14] Compassion fade concerns an individual’s ability to understand statistics in order to develop a mental image and attach meaning to the data leading to a stronger response. Studies that tested charitable giving showed only lower numerate individuals with more abstract images gave lower donations due to a lack of response.[10] Similar research concluded that people with greater ability to think rationally should experience a more linear relationship between number of victims and valuations.[6]

Situational differences

Bystander effect

Compassion fade is affected by situational factors such as the number of people available to help that in turn affects the emotional processes responsible for a person’s motivation to help. The bystander effect is the concept that people are less willing to help in the presence of other people than when they are alone. Research in the late 1960’s by Darley and Latane found only 62% of people were motivated to offer help when in a group greater than five people.[15] Similar research in relation to helping behaviour found diffusion of responsibility played a large role in decreasing an individual’s motivation to help.[16] The effects of the bystander effect on compassion fade is heightened where the number of people in need of aid increases, the perceived burden of responsibility on an individual decrease.[15]

Associated effects and outcomes

Identifiable Victim Effect (IVE)

Identifiable Victim Effect refers to the concept that people are more willing to help a single, identifiable victim than multiple, non-identified ones. Also known as 'The Singularity effect'.[17]

The singularity effect has been found to work even in the circumstance of an individual victim contrasted against a pair of victims. When a charity presents two victims over a singular victim results show that a significantly larger amount of donations are made towards the singular victim. Less affect was also found to be felt for the paired victims.[6] This finding provides evidence of how compassion fade is caused by emotional reaction to a stimulus, as when people feel less affect, they are less likely to donate or provide help towards a cause. The researchers also measured the level to which participants believed their donation would make a difference to the children’s lives. Comparisons between the singular child condition and the paired children condition show there was not a significant difference in perceived probability that the donation will improve their lives.[6] This shows how perceived utility is not causing this effect of compassion fade. Instead of making rational judgements in line with the expected utility theory the singularity effect shows how compassion fade is the result of making decisions via the affect heuristic.

There have also been other proposed reasonings for the singularity effect. It has been proposed that the singularity effect occurs due to prospect theory.[6] This reasoning states that the singularity effect occurs because two is not perceived by the brain to have twice the utility of one so there is a diminishing sense of utility as the sample size increases. Additionally, other explanations state that the singularity effect only occurs when people have no prior knowledge to the situation they are making a decision on. In a study which looked at donations to help pandas, environmentalists evenly donated to both the single panda in need and a group of 8 pandas, whereas non-environmentalists donated a significantly larger amount to the single panda.[12] This shows how when participants are led to decide as an emotional response, as the non-environmentalist did, compared to those who already had substantial knowledge there is more evidence of compassion fade. This effect of compassion fade does not engage system two and only occurs when we are reliant on system 1.

Pseudo-inefficacy

Pseudo-inefficacy means people are less willing to provide aid once they become aware of the people, they are unable to help. This is because people’s willingness to help is motivated by the perceived efficacy of their contribution.[18] Pseudo-inefficacy is influenced by self-efficacy (i.e. perceived ability to help) and response efficacy (i.e. the expected effect of help). Evidence shows increasing self-efficacy increases perceived response efficacy thus increasing charitable behaviour.[19]

The Prominence Effect

The prominence effect is a situation where an individual favour the option that is superior based upon the most important attribute. In circumstances where more socially desired attributes are given priority, the decision is more easily accepted and justified.[18][20]

The Proportion Dominance effect

The proportion dominance effect explains how people are not motivated to save the maximum number of lives but are motivated to help causes which have the highest proportion of lives saved.[21]

Real-world effects

Provision of aid

Compassion fade is illustrated by the reluctance to respond to crises in a global scale affecting large numbers of people. Evidence shows that compassionate behaviour (i.e. financial donations, acts of service) diminish as the number of those in need increases.[1][12]

Research on charitable donations indicates donations are negatively related to the number of people in need. For example, in 2014 the Ebola outbreak saw the loss of over 3400 lives and donations to the American Red Cross was $100,000 over a six month period. However, in 2015 a crowdfunding campaign for a child in New York to visit Harvard raised over $1.2 million in a one-month period.[10]

Environmental crises

Compassion fade research is extended to the environmental domain where the lack of response to environmental challenges, such as climate change, pose a threat to millions of unidentified victims.[12]

However, studies have shown the effects of compassion fade may differ are non-human animals. An experiment in 2004 by Hsee and Rottenstriech tested the identifiable victim effect as an outcome of Compassion fade. The researchers found the donations to help a single versus a group of four pandas was not significantly different. A study by Hart in 2011, found that people information about the detrimental effects of climate change on polar bears elicited a stronger response when presented with a large number of polar bears rather than a single identifiable one. In 2011 Ritov and Kogut demonstrated identifiable victim effects only occurred when helping out-group members.[12] Researchers concluded these findings suggest the extent of environmental compassion fade is more subject to individual differences and perceptions of non-human lives.[20]

See also

References

- Butts, M. M., Lunt, D. C., Freling, T. L., & Gabriel, A. S. (2019). Helping one or helping many? A theoretical integration and meta-analytic review of the compassion fade literature. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 151, 16–33. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.12.006

- Morris, S., & Cranney, J. (2018). Chapter 2 The imperfect mind. The Rubber Brain (pp. 19–42). Australian Academic Press.

- Ahmed, F. (2017). Profile of Paul Slovic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,114(10), 2437-2439. doi:10.2307/26480045.

- Slovic, Paul; Finucane, Melissa L.; Peters, Ellen; MacGregor, Donald G. (2007-03-16). "The affect heuristic". European Journal of Operational Research. 177 (3): 1333–1352. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2005.04.006. ISSN 0377-2217.

- Kahneman, Daniel (2003). "A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality". American Psychologist. 58 (9): 697–720. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.58.9.697. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 14584987.

- Västfjäll, Daniel; Slovic, Paul; Mayorga, Marcus; Peters, Ellen (18 June 2014). "Compassion Fade: Affect and Charity Are Greatest for a Single Child in Need". PLOS ONE. 9 (6): e100115. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j0115V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100115. PMC 4062481. PMID 24940738.

- McAuliffe, William H. B.; Carter, Evan C.; Berhane, Juliana; Snihur, Alexander C.; McCullough, Michael E. (May 2020). "Is Empathy the Default Response to Suffering? A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Perspective Taking's Effect on Empathic Concern". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 24 (2): 141–162. doi:10.1177/1088868319887599. ISSN 1088-8683.

- Butts, M. M., Lunt, D. C., Freling, T. L., & Gabriel, A. S. (2019). Helping one or helping many? A theoretical integration and meta-analytic review of the compassion fade literature. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 151, 16–33. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.12.006

- Johnson, J. (2011). The arithmetic of compassion: rethinking the politics of photography. British Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 621-643. doi: 10.1017/S0007123410000487.

- Dickert, S., Västfjäll, D., Kleber, J., & Slovic, P. (2012). Valuations of human lives: normative expectations and psychological mechanisms of (ir)rationality. Synthese, 189, 95-105. doi: 10.1007/s11229-012-0137-4.

- Slovic, P. (2010). If I look at the mass I will never act: psychic numbing and genocide. Emotions and Risky Technologies, 5(3), 37-59. doi:10.1007/9789048186471.

- Markowitz, Ezra M.; Slovic, Paul; Vastfjall, Daniel; Hodges, Sara D. (2013). "Compassion fade and the challenge of environmental conservation". Judgment and Decision Making. 8 (4): 397–406.

- Cameron, C. D., & Payne, B. K. (2011). Escaping affect: How motivated emotion regulation creates insensitivity to mass suffering. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(1), 1–15. doi: 10.1037/a0021643.

- Olsen, Asmus Leth (2016-09-22). "Human Interest or Hard Numbers? Experiments on Citizens' Selection, Exposure, and Recall of Performance Information". Public Administration Review. 77 (3): 408–420. doi:10.1111/puar.12638. ISSN 0033-3352.

- Hortensius, Ruud; de Gelder, Beatrice (August 2018). "From Empathy to Apathy: The Bystander Effect Revisited". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 27 (4): 249–256. doi:10.1177/0963721417749653. ISSN 0963-7214. PMC 6099971. PMID 30166777.

- Seppala, Emma, editor. Simon-Thomas, Emiliana, editor. Brown, Stephanie L., editor. Worline, Monica C., editor. Cameron, C. Daryl, editor. Doty, James R. (James Robert), 1955- editor. The Oxford handbook of compassion science. ISBN 978-0-19-046468-4. OCLC 974794524.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kogut, T., & Ritov, I. (2005). The singularity effect of identified victims in separate and joint evaluations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 106–116.

- Kunreuther, H., Meyer, R. J., & Michel-Kerjan, E. O. (2019). The Future of Risk Management. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Sharma, E., & Morwitz, V. G. (2016). Saving the masses: The impact of perceived efficacy on charitable giving to single vs. Multiple beneficiaries. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 135, 45–54. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.06.001

- Cameron, C. D., & Rapier, K. (2017). Compassion is a motivated choice. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong & C. B. Miller (Eds.), Moral psychology: Virtue and character (p. 373–408). MIT Press. https://doi-org.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/10.2307/j.ctt1n2tvzm.29

- Erlandsson, Arvid; Björklund, Fredrik; Bäckström, Martin (2014). "Perceived Utility (not Sympathy) Mediates the Proportion Dominance Effect in Helping Decisions". Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 27 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1002/bdm.1789. ISSN 1099-0771.