Coastal coal-carrying trade of New South Wales

The Coastal coal-carrying trade of New South Wales involved the shipping of coal—mainly for local consumption but also for export or coal bunkering—by sea to Sydney from the northern and southern coal fields of New South Wales. It took place in the 19th and 20th Centuries. It should not be confused with the export coal trade, which still exists today. There was also an interstate trade, carrying coal and coke to other Australian states that did not have local sources of black coal.

Coal was found to the north and south of Sydney in the last years of the 18th-Century by colonial settlers. Coal seams run under Sydney but at great depth and mining these seams proved impractical. As Sydney grew in size as a city and as a major port, coal was needed for steamships, town gas production and other industrial uses.

Small ships—colloquially called 'sixty-milers'—carried coal to Sydney from coal ports that were established on the northern and southern coalfields of New South Wales. The coastal trade was well established by the time Sydney was first linked to the coalfields by railways. Significant customers for coal were situated on the foreshores of Sydney Harbour, the Parramatta River, and to a lesser extent Botany Bay. Steamships using Sydney loaded bunker coal there.

During the heyday of the coastal trade, Sydney was dependent upon a constant supply of coal arriving by sea, particularly for the production of town gas and for bunkering operations. As the uses of coal declined, so did the coastal trade in the last three decades of the 20th-Century. It ended finally, around the turn of the 21st-Century, and is now largely forgotten. Few remnants of the once extensive coastal coal-carrying trade exist today.

Discovery of coal by colonists in New South Wales

Coal was used as a fuel by the Awabakal people, the original inhabitants and traditional owners of what is now Lake Macquarie and Newcastle. Their word for coal was "nikkin". Evidence of coal use has been found in beach and dune middens, on Lake Macquarie at Swansea Heads and Ham's Beach, and on the Central Coast at Mooney Beach.[1]

A group of escaped convicts led by a married couple William and Mary Bryant were the first Europeans to find and use Australian coal, at the end of March 1791. They found ‘fine burning coal’ near a ‘little creek’ with cabbage tree palms ‘about 2 degrees’ north of Sydney, 'after two days sailing'. This first hand account of the discovery—written by one of the party James Martin—was found in a collection of manuscripts and published in 1937.[2] The escapees never returned to Sydney and their discovery of the coal remained unknown, until after they were recaptured at Kupang. William Bryant also wrote an account that is now lost but William Bligh—later a governor of New South Wales—saw it, when he visited Kupang in 1792. Bligh made a summary of Bryant's account in his log and quoted him as saying, "Walking along shore towards the entrance of the Creek we found several large pieces of Coal—seeing so many pieces we thought it was not unlikely to find a Mine, and searching about a little, we found a place where we picked up with an Ax as good Coals as any in England—took some to the fire and they burned exceedingly well".[3] It is likely that the location was near the entrance to Glenrock Lagoon, where coal is exposed in the sea cliff and which was later the site of the Burwood Colliery.[4]

Survivors of the wreck of the Sydney Cove reported seeing coal south of Sydney, after completing their 700 km trek along the coast in May 1797. The explorer George Bass was tasked to confirm the discovery, and, in July 1797, he reported seeing a coal seam “six foot deep in the face of a steep cliff which was traced for eight miles in length”[5][6] (Sites where coal outcrops are visible along the coast south of Sydney include Coalcliff, where coal outcrops in the sea-cliff, and near the ocean pool at Wombarra and Brickyard Point, Austinmer, where coal outcrops in the headlands.)

In September of the same year, Lieutenant John Shortland reported coal outcropping on the southern side of the Hunter River—first known as the Coal River—near to its mouth, at what is now Newcastle.[5] Shortland's ‘discovery’ may have been prompted by an earlier report—provided by a party of fishermen in 1796—of a river with coal, to the north of Sydney and south from Port Stephens, but he is credited with the discovery of the Hunter River and the northern coalfields.

In July 1800, Captain William Reid—mistaking Moon Island for Nobby's and the entrance to Lake Macquarie at Swansea Heads for the mouth of the Hunter River—obtained his cargo of coal for Sydney from a seam outcropping in the southern headland at the lake's entrance—a headland since known as ‘Reid’s Mistake’—and so accidentally revealed to the settlers the coastal coalfields of Lake Macquarie.[7] Awabakal people had used the coal at Swansea Heads for over a thousand years.[1] It was only upon his return to Sydney that Reid found that he had not travelled far enough north to have reached the Hunter River.

Coal was also found during July 1801 by the expedition, led by Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson, to the Hunter Valley inland from Newcastle. This area would later become the vast South Maitland Coalfields.[8]

The discovery of the western coalfields did not occur until after the Blue Mountains had been crossed in 1813. Coal outcrops low in the cliffs of some valleys of the Blue Mountains and on their western side near Lithgow. William Lawson found coal near Mt York in the area later known as Hartley Vale, in 1822.[9][10] Apart from local use, western coal could not be exploited until the railway from Sydney crossed the Blue Mountains in 1869, and soon after that there were mines in the area around Lithgow.

That coal had been found so readily, by colonial settlers with no experience of mining and little knowledge of their new country, so soon after the first European settlement, implied that the resource was widespread and plentiful. That proved true; an immense coal resource existed in New South Wales.[11] Coal is still being mined within the Sydney Basin more than two centuries later. Some individual mines had been worked for well over a century. Indeed, it is only the more recent increased rate of extraction—for the export market—that will see the exhaustion of commercially viable reserves around the middle of the 21st-Century.

Reasons for the trade

Coal for Sydney

Coal was needed in Sydney to feed the production of town gas (from 1841 to 1971), as bunker coal for steamships, and as fuel for industrial and hospital heating boilers. Brickworks were a significant user of coal as a fuel. In the C19th and very early C20th, there was also some demand for coal as a fuel for domestic heating. Some coal also was trans-shipped and exported from Sydney.

Coal seams extend under Sydney but the huge depth of these seams has resulted in only very limited mining activity in Sydney.[12] The coal seams of the Sydney Basin outcrop to the north, south and west of Sydney. The Metropolitan Colliery, 45 km south of Sydney at Helensburgh, is the closest commercially viable coal mine.

Given the short distances involved, it is not immediately obvious why coal would be carried to Sydney by sea. Not all coal consumed in Sydney arrived by ship; the railways also carried coal to Sydney. However, the main railway lines from Sydney to the north and south were not completed until the late 1880s. By that time, some mines were already well established and connected to nearby ports by local rail lines, the shipping trade was well established, and many major customers already had facilities on the waterfront of the natural port of Sydney Harbour and were without a rail siding. Some mines had been designed to ship coal by sea only, for example Coalcliff (up to 1910) and the Wallarah Colliery at Catherine Hill Bay. Most of the local rail lines to the mines were privately owned and used rolling stock that was not to the standards expected of main line rail operations—for example wagons without air brakes—and operation over government-owned lines was restricted to specific lines and not allowed on others.

Coal bunkering of steamships in Sydney Harbour was a natural fit for the coastal coal trade. Sixty-milers could moor alongside a steamship and directly transfer coal to the ship's bunkers.[13] After 1920, coal could be off-loaded at the purpose-built bunkering facility, the Ball's Head Coal Loader.[14] Coal bunkering also took place at a 'coal wharf' at Pyrmont.[15]

The New South Wales Government Railways were large users of coal. But once the railway from Sydney reached the western coal-fields in 1869 and later the other coal fields, they had no need for coal carried in ships.

Four of the electrical power stations in Sydney—Bunnerong on Botany Bay, and White Bay, Pyrmont and Ultimo on Sydney Harbour—were supplied with coal by rail. All these power stations were situated close to the waterfront but that was to obtain cooling water not port access.[16] Two of the power stations—Ultimo and White Bay—initially were operated by the railways and all the power stations in Sydney were built after the rail connections from the coalfields to Sydney were completed. The other power station, at Balmain, had no rail siding. It was coal-fired but also raised some steam by incinerating garbage. Its coal was landed from barges at the waterfront until 1965 [17] and so it seems likely that some or all of the coal for the Balmain Power Station came by sea.

Coal and coke for the other states

In parallel to the coastal trade to Sydney, there was an interstate coastal trade in coal and coke from the same ports to other Australian states, particularly Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania where black coal was needed for steamship coal bunkering, rail transport and industrial purposes and coke was needed for smelting ores.

Ships

The ‘sixty-milers’

Coal was carried to Sydney in ships known as ‘sixty-milers’. The name refers to the approximate distance by sea—in nautical miles—from the Hunter River to Sydney.

The heyday of the 'sixty-milers' was from around 1880 to the 1960s. In 1919, a Royal Commission identified twenty-nine ships engaged in the coastal coal-carrying trade.[18]

The Interstate ships

There was almost no overlap in the ships used in the two coastal coal trades. The interstate ships were larger than most 'sixty-milers' [19] and making longer voyages needs different crewing arrangements and larger coal bunker capacity..

The ship owners and operators

In the earlier years of the trade, there were many owners and operators, sometimes just owning or operating on charter just one vessel. Owners of the 'sixty-milers', during this period, most typically were coal-mines (such as Coalcliff Colliery and Wallarah Colliery), or coal-shippers or merchants (such as Scott, Fell and Company, G.S.Yuill & Co. ),[20] The southern coalfield collieries (Coalcliff Collieries, etc.) owned their own ships but most were chartered to the Southern Coal Owner's Agency, which operated the ships. Later companies that both owned coal mines and were also coal merchants (such as R.W.Miller and Howard Smith Ltd) owned ships and ownership became more concentrated.

In the later years of the trade, one of the dominant owners was R.W. Miller[21] and its successor companies. However, due to company takeovers and cross-ownership between R.W. Miller, Howard Smith Limited and Coal and Allied Industries, it is somewhat difficult to track ownership of vessels and loading assets of these firms. In 1989, Howard Smith took full ownership of R.W.Miller. Another dominant owner in the later years of the trade was the Melbourne shipping company McIlwraith McEachern, owners of the sixty-milers whose names included 'Bank' (Mortlake Bank, etc.) [22] Ownership was sometimes difficult to follow; the Hexham Bank may have been described as an 'R.W. Miller' ship when in fact it was on charter to that company from its actual owners McIlwraith McEacharn. Ships of course were bought and sold and changed ownership, while still carrying coal cargoes for their new owners; sometimes the change in ownership also resulted in the ship's name changing, such as when the Corrimal became the Ayrfield.

In contrast to the 'sixty-milers', the owners of the interstate coastal ships were usually more traditional ship-owners, some of whom specialised in carrying coal and coke.[19]

Coal ports & operations

Northern Coalfields — Hunter Valley & Lake Macquarie Region

Coal from the northern coalfields was loaded at Hexham on the Hunter River, Carrington (The Basin, The Dyke) near Newcastle, on Lake Macquarie, and at the ocean jetty at Catherine Hill Bay. In the early years of the trade, coal was loaded at Newcastle itself, on the southern bank of the Hunter River, at the river port of Morpeth, and at a wharf at Reid's Mistake at Swansea Heads.

The coalfields to the north of Sydney had the advantage that the Hunter River and its estuary, while not ideal, could be used as a port. Mining commenced on the northern fields first. The first coal mines were initially operated by the government using convict labour. Sporadic mining operations started around what is now Newcastle and, in 1799, a cargo of coal was shipped to Bengal aboard the Hunter. The first ‘permanent’ mine at Newcastle was opened in 1804.

When Newcastle ceased to be a penal colony in 1821, the government continued to operate the mines. Commissioner Bigge had recommended that the mines be given over to private operation. In 1828, there was an agreement struck between the Secretary of State for colonies and the Australian Agricultural Company that made coal mining a monopoly of that company.[23] One other company was able to persuade the government to allow it to mine coal from 1841, the Ebenezer Colliery at Coal Point on Lake Macquarie.

.jpg)

The monopoly was broken when challenged in 1847 by the Brown family, who began mining coal at Maitland and using the river port of Morpeth and undercut the price of coal mined by the AAC. Coal was accessible in many places throughout the Hunter Valley and on both the eastern and western shores of Lake Macquarie. Once the monopoly was broken, many mines were soon in operation throughout the northern coalfields. At the end of the C19th, the four most important companies on the northern field were the Australian Agricultural Company, J & A Brown, Newcastle Wallsend and Scottish Australian (Lambton Colliery). Of these, only the Scottish Australian was not a member of the Associated Northern Collieries. This was essentially a cartel that divided production as quotas for each of the participating colliery owners. There was a monetary mechanism under which collieries selling above their quota compensated those selling under their quota. To avoid companies just leaving coal in the ground, quotas were adjusted based on actual sales for the previous year. The arrangement was known as "the Vend" and operated for most of the years between 1872 and 1893, when it collapsed due to competition in the export market.[24]

Many collieries on the northern coalfield of NSW were named after collieries in the United Kingdom. Other names referenced the coal seam being mined and that confused the locality and identity of the mine further. With changes of ownership, mine names often changed and sometimes names associated with good-quality coal were moved to completely different collieries.

Most mines of the northern coalfields were connected to the ports at Hexham and Carrington by an extensive network of railway lines; some were government lines and others were privately owned. Coal was loaded into four-wheel wagons owned by the mining companies. The type of four-wheel wagon used consisted of a frame with wheels and a removable wooden hopper. Trains of wagons were hauled to the port, where the removable hoppers were lifted out of the frame by a crane and dumped by opening the bottom of the hopper. They were known as 'non-air' wagons because they did not have air-brakes.

At their peak, there were 13,000 of these ‘non-air’ wagons in service, belonging to around sixty operators. Larger modern bogie wagons were introduced in the 1960s and ‘non-air’ wagons were banned from Port Waratah in 1974 but continued to be used to bring coal to Hexham. There were still 3,000 in use in 1975 and 900 when the Richmond Vale Railway closed in September 1987. 'Non-air' wagons came in different capacities between 7 and 12.5 tons. Large letters on the side of the wagon identified the owner, and small letters its capacity.[25]

The Hunter River ports

Ships bound for the river ports of Newcastle (Port Hunter), Carrington, Hexham and Morpeth had first to enter the river mouth between Nobby's Head and Stockton.

_c.1878_(_Illustrated_Sydney_News_and_New_South_Wales_Agriculturalist_and_Grazier_Sat_23_Mar_1878_Page_13_).jpg)

The mouth of the Hunter was difficult for sailing ships heading south to Sydney. Sailing ships leaving port could not negotiate the east-north-east facing channel leaving the river, when winds favourable to a southern passage were blowing. From 1859, these ships were towed out by steam tugs and the situation improved.[27] The construction of the breakwater and land reclamation between Nobby's Head and Newcastle increased the safety of the port.

Just to the north of the river mouth is the notorious Oyster Bank, actually a series of shifting sandbanks. At least 34 vessels were lost on the Oyster Bank. Construction of the northern breakwater somewhat reduced the hazard to shipping entering the river.[29][30][31][32] Around the same time as the northern breakwater was built over the Oyster Bank, a southern breakwater was extended from Nobby's on the southern side of the river.[33]

The shallowness of the entrance to the Hunter River continued to be a limitation on shipping into the 1920s[34] and a hazard during bad weather.[35] Work continued to improve the river mouth, culminating in the excavation of a deep channel 600 feet wide, with 27 feet of water depth, effectively removing the rock bar at the river's mouth.[36][37]

Newcastle (Port Hunter)

Coal was shipped from Newcastle to Sydney, from around 1801 onward. Initially mines were located in what is now the inner-city of Newcastle and coal was loaded from wharves on the southern bank of the Hunter River. Newcastle was the main port, during the time of the Australian Agricultural Company's monopoly on the mining of coal (1828–1847). The A. A Co. built the first rail line in Australia, from its mines to the Newcastle port.

By the 1860s, Newcastle was a busy coal port with both the privately-owned coal staiths and the government-owned Queen's Wharf in operation. The Queen's Wharf was connected to the Great Northern Railway[28]—opened as far as East Maitland in 1857—and had six steam cranes used for loading coal.[38][39] The westernmost staithes were the privately-owned staithes of A.A. Co., which were connected to their private railway line. The stathes to their east were connected to the Great Northern Railway and to the Glebe Railway.[28][40]

With the completion of the port at nearby Carrington and the end of coal mining in Newcastle itself, the importance of the old port of Newcastle as a coal port, declined. Steam cranes were relocated from Newcastle to the Dyke at Carrington.[41][38]

Morpeth

.jpg)

The river port at Morpeth on the Hunter River was used to load coal mined in the Maitland area by J & A Brown from around 1843. Coal was also needed to recoal steamers at the port.

Although it lies far downstream from the tidal limit,[42] Morpeth was the effective head of navigation of the Hunter, because farther upstream there were many large bends in the river between Morpeth and Maitland. Aside from greatly increasing the distance by water to Maitland, these bends were difficult for vessels to navigate. It also lay just upstream of the confluence of the Hunter River and the Paterson River, below which the river broadens. Morpeth had been a river port from the 1830s.[43]

The importance of Morpeth as a port began to decline, once the railway from Newcastle reached East Maitland in 1857. A branch railway to the old port was opened in 1864. There were coal staiths[44] and a railway siding for these at Morpeth, These new staiths were still unfinished in early 1866.[45] Once completed, the new Morpeth staithes were rarely used.[46] By the late 1870s, little coal had been loaded there[47] and, by the late 1880s, the coal staiths were in a derelict and dangerous condition.[48] Construction of the Morpeth Bridge, downstream of the staiths, in 1896 to 1898, ended any possibility of their revival, as only very small steamers could pass under it.[49] Morpeth continued as a port but mainly for agricultural products.

Morpeth was disadvantaged by its distance up river, the shallowness of the river, and the impact of river floods.[50] It was overtaken, as a coal port, by the downstream river ports at Newcastle, Hexham, and Carrington, which had better railway connections to the coalfields, could handle greater volumes and larger vessels, had better port facilities, and were closer to Sydney.[51] However, local interests continued to advocate coal loading at Morpeth.[52]

Regular shipping port operations at Morpeth ceased in 1931,[53] but some shipping continued in a small way after that time.[54] Due to wartime constraints on transporting coal by rail, in 1940, coal from Rothbury was shipped at Morpeth but not directly to Sydney; it was brought to the port by road and then sent by barge for transshipment at a downstream river port.[55]

The river gradually silted up[56]—no longer being dredged[57]—leaving Morpeth to fall into further decline. The branch line closed in 1953.[58][59]

Carrington — The Dyke and The Basin

.jpg)

The port at Carrington was the largest of all the coal ports of the coastal coal-carrying trade. The Basin and the Dyke could handle larger ships and were also used for coal export and coal bunkering, as well as loading 'sixty-milers'.

The area was originally a low-lying island, Bullock Island, within the estuary of the Hunter River, which was partially submerged at high tide. Sailing ships using the old port of Newcastle tipped stone ballast in the area and, with other reclamation work, the line of The Dyke was created by 1861. The Dyke had the effect of constraining the channel of the Hunter River, so that the natural flow and tidal movement of the river tended to scour sediments from the river floor and maintain a deep-water port. Land was reclaimed behind the original Dyke, which became the large rail-yard for the port. Coal was loaded at The Dyke from 1878.

The Basin is an artificial harbour, to the west of The Dyke, which opens into the junction of Throsby Creek and the Hunter River. It was created by dredging and completed in 1888. The Basin was also used to load coal.

The Carrington coal-loaders used twelve hydraulic cranes powered by water under pressure supplied from a pumphouse nearby. There were also three steam cranes. In 1890, this government-operated facility was capable of loading a total of 12,000 tons per day. There were also some privately operated chutes capable of another 3,000 tons per day.[60] Later some electrically operated cranes were added. The hoppers of rail wagons were lifted by these cranes and the coal dumped directly into the holds of ships.

Hexham

Hexham is located on the Hunter River upstream from Newcastle. It is where the Hunter River separates into its north and south channels. Upstream of Hexham the river, although still tidal, becomes meandering and more difficult for vessels to navigate. There were three coal loaders at Hexham.

.jpg)

The most downstream loader was J & A Brown's staithes that were supplied with coal by the Richmond Vale Railway, via a right-angle crossing (across the Main North government line), from 1856 until November 1967.[62]

The next loader upstream was the R.W.Miller coal loader, located next to the Hexham Bridge, which was built in 1959 and supplied only by road. After the merger of R.W. Miller with Coal & Allied in the mid-1980s, it was used by Coal & Allied to load coal washed at the Hexham Coal Washery and destined for Sydney. This loader was closed 1988 after the closure of the washery.[62]

The most upstream loader was built in 1935 for the Hetton Bellbird Collieries and was sold to the Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company in 1956. It was supplied via the South Maitland Railway up to the East Greta Exchange Sidings (near Maitland) and from there via the Main North (government) railway to the Hetton Bellbird Sidings at the loader. The coal was dumped at a dump station and was transferred via conveyor across the main line and highway to a ship-loader. The loader was closed in 1972 and demolished during 1976.[62]

As a river port, care had to be taken so ships made use of the tides to avoid running aground in shallow Fern Bay, when laden with coal and heading downstream, via the North Channel of the Hunter, to the sea.[63]

Lake Macquarie

Lake Macquarie could handle only very small craft due to the shallow opening of the lake to the sea at Swansea. Only the very smallest of the 'sixty-milers'—ships like the Novelty,[64] Commonwealth,[65] and Himitangi[66]—were suitable. A breakwater and dredging of the channel allowed these ships to pass the shallow entrance.[67]

The South Hetton Colliery shipped coal from a wharf—probably at Coal Point—on the western shore of Lake Macquarie.[68] Coal was also loaded at Green Point on the eastern side of the lake.[67] A wharf on the south side of Swansea Channel, near the Reid's Mistake Headland was used as a transhipment location for Sydney in the 1840s. There were other collieries near to the northern, eastern or western shores of the lake but these were connected to railway lines and sent their coal to Carrington and some for local consumption at the Newcastle Steelworks.

.jpg)

Catherine Hill Bay

Catherine Hill Bay was the only ocean jetty port on the northern coalfields. Coal from the Wallarah Colliery was loaded here for Sydney and Newcastle. By using an ocean jetty, this colliery could exploit the coal seams of Lake Macquarie, without ships needing to enter the Swansea Channel. The port could still be dangerous, under unfavourable weather conditions, and some ships came to grief there.

It was the last port used by the coastal coal trade in 2002. Coal was last loaded for the short trip to Newcastle, where it was loaded for export.[70] The Wallarah Collliery closed in the same year,

Southern Coalfields — Illawarra Region

Although lying much closer to Sydney, the southern coalfields were not developed early, due to the absence of any natural port. Coal in the southern coalfields was generally more easily won than in the northern field. The coal outcropped in sea cliffs or part way up the Illawarra Escarpment and adit mining was feasible. Adits were less costly to construct and operate than the shafts and sloping drifts of the northern coalfields. The southern coalfields could be worked profitably, if the problem of shipping could be solved. The absence of a suitable port held back development of the southern mines, until around 1849 when the Mt Kiera mine opened.

Coal from the southern coal fields, at various times, was loaded at Wollongong Harbour and Port Kembla and at the ocean jetty ports: Bellambi; Coalcliff; Hicks Point at Austinmer; and Sandon Point, Bulli. Port Kembla was originally an ocean jetty port but two breakwaters were added later to provide shelter.

Loading at the southern coalfield jetty ports typically used four-wheel wagons with hoppers fixed to the frames, which were tipped into chutes that led to high staithes from which the collier alongside the jetty or wharf was loaded. At Wollongong Harbour only, some loading was done by crane using wagons with removable hoppers, similar in concept to the ones used in the northern coalfields. After 1915, four-wheel bottom dump wagons were used to bring coal to the new No.1 Jetty at Port Kembla, via an unloading rail loop and dump station.[71] This bottom-dumping operation was similar in concept to the coal-handling practice of today.

Unlike the northern fields, mines of the southern coalfield were usually named after a locality or geographical feature and their names rarely changed over their lifetime. The number of mines was also less and the mines tended to have longer lives.

Most of the southern coalfield mines were members of the Southern Coal Owners' Agency, which had as one of its aims 'prevention of ruinous competition'. It was a cartel-like organisation, controlling production volume, prices, and transport costs, but only for the southern coalfields. It lasted from 1893 to 1950, being renewed every few years by agreement. Although the collieries that were members owned 'sixty-miler' ships, those ships were chartered by the Agency. The Agency managed the operations of the ships and paid the owner a monthly fee based on each ship's capacity. Although the operation of the ships may not have been profitable, the collieries seem to have seen controlling the shipping of their coal as important to ensure reliable delivery, and as a necessary cost. Collieries received an initial low payment upon delivery of their coal to a customer but also later received a share of the actual profits from all sales, in proportion to their market share.[72]

Wollongong Harbour

Wollongong was for a time the only safe anchorage on the southern coalfields and the third largest port in New South Wales.

The coal port at Wollongong Harbour consisted of the man-made Belmore Basin and the 'Tee Wharf'. On Belmore Basin, there were four coal staithes on the western side of the basin and two steam cranes on the eastern side. Loading at the 'Tee Wharf' was by a single steam crane. The 'Tee-Wharf' was somewhat exposed to weather from the north and north-east; the existing northern breakwater was not built until 1966-67.

The port was connected to the Mt Kiera and Mt Pleasant Collieries by rail lines operated by the respective collieries. Originally these were horse-drawn but later used steam locomotives.

From 1875 to 1890, there was a cokeworks, which converted unsaleable fines to coke, some of which was loaded at the port for Sydney.

By 1927, there was only one coal staith in operation at Wollongong. The last coal was loaded there in 1933, by which time it had been eclipsed as a coal port by Port Kembla.[74]

Port Kembla

From 1883, coal was shipped from an ocean jetty on the beach just to the north of a rocky headland lying to the north of Red Point and Boiler's Point. This new port was named Port Kembla, after the Mount Kembla mine from where the coal was transported by rail.

A second jetty belonging to the Southern Coal Company was opened in 1887, which loaded coal sent by rail from the Corrimal Colliery.

In its earlier years—much like the other ocean jetty coal ports—Port Kembla was exposed to rough seas during bad weather, Between 1901 and 1937, first an eastern breakwater and then a northern breakwater was constructed, resulting in a large protected and safe anchorage now known as the ‘Outer Harbour’.

A new coal jetty was built to the north of the two existing coal jetties. The new coal jetty opened in 1915 and became 'No.1 Jetty', the Southern Coal Jetty became No.2 Jetty, and the Mt Kembla Jetty became Jetty No.3.[75]

By 1937, the No.1 Jetty was loading coal from all the southern mines that shipped coal by sea, except those mines still using Bellambi or Bulli. After 1952, Port Kembla was the only coal port on the southern coalfields.

The No.1 Jetty remained in service until it was replaced in 1963, by a new export coal loader located on the new ‘Inner Harbour’. Port Kembla remains a major coal export port.

Port Bellambi

_(27809523725).jpg)

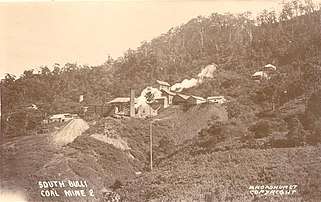

There were originally two jetties at Bellambi, the South Bulli Jetty named after the mine of the same name and the Bellambi Coal Co. Jetty used by the Model Mine at Woonoona. The South Bulli Jetty built in 1887[77][78][79] was on Bellambi Beach immediately to the north of Bellambi Point. The Bellambi Coal Co. Jetty (also known as the "Woonoona Jetty") built in 1889[80] was located on a small rocky outcrop just to the north of the South Bulli Jetty, The port had also been the site of an earlier coal jetty completed around 1858 but only used for a relatively short time.

The Bellambi Coal Co. Jetty was damaged in a storm in 1898[81] and thereafter all coal went across the South Bulli Jetty.[82]

Coal was sent from the mines by rail to the jetty, where there were two rail tracks on the jetty—one for full wagons and the other for empty wagons—and two loading chutes (one for each hold of a 'sixty-miler').[79]

The wagons were separated for tipping. One end of the coal wagon was raised by a steam ram, acting on a wagon axle, tipping the coal through a hinged panel in the other end. The coal then passed through a chute, directly into one hold of the ship moored alongside the jetty.[83] In 1909, six colliers were loaded with a total of 4,500 tons in 14-hours.[84]

Bellambi was a particularly dangerous port. Bellambi Point protected the jetties from the south but its reef extends 600m to seaward[85] and was a hazard to shipping. In total, twelve ships were wrecked at Bellambi between 1859 and 1949, of which seven ran aground on the reef.[86]

The South Bulli Jetty operated until 1952. The jetty partially collapsed in 1955 and was demolished in 1970.

Coalcliff

.jpg)

The Coalcliff Colliery, opened in 1878, was originally developed as a jetty mine. Coal from the mine, after screening, was brought directly onto the jetty. This arrangement made working the mine difficult, as there was limited storage for mined coal and only coal that could be shipped promptly could be mined.[88][89]

The jetty at Coalcliff was the smallest of the southern ocean jetties. It was very exposed to ocean swell, and shifting sand shoals added to the danger by changing the depth of water near the jetty.[90] The jetty was used only by the Colliery's own 'sixty-milers' and then only in favourable weather.

Storms in 1878,[91] 1881 and 1904 caused considerable damage to the jetty, further restricting shipping operations while damage was repaired and the jetty design modified.

In 1910, a shaft was opened that allowed coal from the mine to be transported by rail and the jetty closed by 1912. Although no longer operating its own jetty, Coalcliff Collieries continued to own and operate its sixty-milers, such as the Undola. This may have been so that the jetty mine's quota under the Southern Coal Owners' Agency agreement would still be allocated to the company, in addition to its new quota for the 'new' shaft mine.[92]

.jpg)

Hicks Point, Austinmer

Hicks Point is a small rocky outcrop in the beach in Hicks Bay, just to the north of Brickyard Point, Austinmer, NSW. Even its name is almost forgotten today.

The Hicks Point Jetty was built in 1886 for the North Bulli Coal Company's colliery at Coledale [94] to which it was connected by rail. It was also connected by rail to the Austinmer Colliery.[95] Brickyard Point to the south provided some shelter from southerly weather; today the area is used to launch boats.

Coal was railed from the mine to the jetty in wagons with bottom opening doors, which were opened over a hatchway cut in the jetty deck. The coal flowed onto loading chutes and from there into the hold of the ship.[96]

The jetty was damaged by storms in November 1903.[94] The North Bulli Co. won the right to ship its coal via Port Kembla in 1906.[97] The Hicks Point Jetty was no longer needed and fell into disuse. It was destroyed by fire in 1915.[94]

Sandon Point, Bulli

The Bulli Jetty at Sandon Point was opened in 1863 and used to load coal obtained from the nearby Bulli Colliery.

The Bulli Colliery was bought by BHP in 1937 and thereafter much of its coal went to the Port Kembla steelworks by rail.

The Bulli Jetty was last used by ships in 1943. After closing, it was damaged by storms in 1943,[98] in 1945[99] and in 1949, when the centre section of the remaining structure collapsed and stranded four fishermen at the sea-end.[100][101] Some of the structure was still standing in the mid-1960s but was gone by the end of the decade.[102]

Sydney

Sydney was for many years heavily dependent upon a constant supply of coal for its electricity, town gas, transport and other uses, something made more apparent by the effects of industrial trouble in the coal industry in 1948-49.[103]

Within Sydney Harbour and the Parramatta River, unloading facilities included the Ball's Head Coal Loader at Waverton, AGL gasworks at Millers Point (until 1921) and Mortlake, North Shore Gas Company gasworks at Neutral Bay (until 1937) and Waverton; the Manly Gasworks at Little Manly Point (Spring Cove), and the R.W. Miller bunker facility in Blackwattle Bay. There were coal wharves at Pyrmont on Darling Harbour, where coal was sometimes unloaded[104] but, more commonly, was loaded. Some large industrial customers had their own wharves at which coal was unloaded. There was also a coal loader, the Balmain Coal Loader at White Bay, from around 1935 until it closed in October 1991, but it was only used for loading coal for the most part from the western coalfields near Lithgow.[105] Coal was also unloaded at the Government Pier (or 'Long Pier') at Botany on the northern shore of Botany Bay.

Steamship coal bunkering and export operations

Bunkering by 'sixty-milers'

Steamships requiring bunker coal at Sydney Harbour could have their bunkers loaded directly from a 'sixty-miler' standing alongside. This bunkering operation was common, especially before the mechanised Ball's Head Coal Loader opened in 1920 and before there were mechanised coal hulks in operation. Steamship companies preferred the coal of southern coalfields, because it burned with little smoke.[106] However, bunker coal came by 'sixty-miler' ships from the both the northern and southern coalfields.

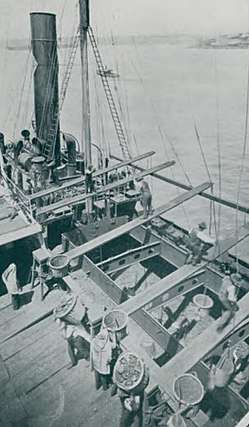

'Coal lumping' gangs

Inside the hold of the 'sixty-miler' workers known as 'shovellers' would shovel the coal by hand into coal baskets that were limited by regulation to a weight of two hundredweight (one-tenth of a ton, or approx. 100 kg). The coal baskets were then hoisted out of the hold of the 'sixty-miler'. A worker—the leader of the gang, known as a 'planksman'—working on a 16-inches wide plank suspended high above the hold of the 'sixty-miler' and level with the steamship's rail, would walk along the plank and swing the suspended basket over the steamship's rail. From there other workers—known as 'carriers'—would carry it on their shoulders and tip it into the steamship's bunker chutes. Inside the steamship's bunkers, other workers known as 'trimmers' distributed the coal within the bunker.[13][106] The work of the winch-driver, while less physically taxing, involved great mental strain; any miscalculation in hoisting or braking, could result in death or serious injury to the others in the gang. These workers, collectively known as 'coal lumpers', may have been the most highly paid casual employees of their time, but their pay recognised the arduous, extremely dirty and highly dangerous nature of the work.[13]

Work was carried out day and night, except in wet weather, so that bunkering was reasonably fast.[106] A complete gang of 1 'planksman', 4 'shovellers', 1 winch-driver, with 4 'carriers' and 'trimmers' could move about 9.5 tons per hour. The number of gangs that could be put on bunkering a ship was set by the receiving space of the ship and the number of planks that could be suspended from gaffs on the masts of the 'sixty-miler'. The Bellambi could suspend sufficient planks to allow twelve gangs to work,[76] allowing a coaling rate of over 100 tons per hour if the receiving ship was of a suitable design.

Such rapid coaling was not without its own hazards. The 5,524 tonne steamer Austral was being coaled—apparently without due care taken of its trim—when it keeled over and sank off Kirribilli Point on 11 November 1882.[107][108]

.jpg)

Semi-mechanised bunkering by 'sixty milers'

Some 'sixty-milers'—such as the Stockrington—had their own lifting gear with grabs and were capable of coaling other ships; these semi-mechanised operations continued after the loader opened at Ball's Head.[110]

Mechanised coal hulks

Mechanised coal hulks were used on Sydney Harbour. Hulks could be loaded at an on-shore loader or from 'sixty-milers', including those with a self-discharging capability such as the Stockrington. Without propulsion of their own, the hulks were towed into position by tugboats. Once alongside the vessel receiving the coal, the mechanised coal hoists aboard the hulk were used to discharge the coal directly to the bunker chutes or bulk cargo holds of the vessel. It seems that it was common practice to coal a ship moored at a wharf, using a mechanised coal hulk with a 'sixty-miler' standing alongside (see photograph).

.jpg)

The Fortuna, a mechanised coal hulk owned by the Wallarah Coal Co., was used for coal bunkering and ship-loading on Sydney Harbour. This strange-looking vessel was a familiar sight on the harbour for the four decades between 1909 and 1949. Her equipment was steam powered, with two 60-foot high grabs on her starboard side, and she was capable of coaling a ship at a rate of 200 tons/hour.[112]

The Fortuna, was launched, in 1875, as a fully rigged, iron-hulled ship, the Melbourne, with accommodation for sixty passengers. She was sold and rechristened Macquarie in 1888 and, in 1903, rerigged as a barque. In 1905, she was sold to Norwegian interests. In 1909, she was stripped of her tall masts and figurehead—in the likeness of Queen Victoria—and was converted to a mechanised coal hulk, the Fortuna.[112][113][114][115]Fortuna was also the name of an earlier coal hulk.[116]

.jpg)

By early 1925, the Bellambi Coal Company had introduced its own mechanised coal hulk, fitting an old coal hulk Samson with two coal hoists.[118] This vessel was still working into the early 1930s at least.[119] The coal-handling equipment aboard Sampson was powered electrically and capable of coaling at 240 tons per hour.[120] The 'sixty miler' Bellambi (formerly Five Islands) was modified so that its holds could be readily accessed by the grabs of Sampson.[121]

After lying idle in Sydney Harbour from 1922, the barque Muscoota was sold in 1924 and converted—at the Mort's Dock, in 1925—to be a second mechanised coal hulk for Wallarah Coal Company.[122][123] As a coal hulk, the Muscoota had only one coal hoist.[117] In 1943, she was refitted and was towed to Milne Bay, New Guinea, in early 1944, to recoal ships there. She was involved in an accident with a Dutch steamer during a storm, following which she was towed to nearby Discovery Bay, where she sank slowly.[124][125]

The Ball's Head Coal Loader

.jpg)

The Ball's Head Coal Loader, at Waverton on the Lower North Shore, opened in 1920. It was owned and operated by the Sydney Coal Bunkering Co., a subsidiary of the Union Steamship Co.. It was mainly used for bunkering steamships using the port of Sydney but also supplied some coal to local hospitals and other customers needing heating coal.[14]

Coal was unloaded, from the holds of 'sixty-milers' moored parallel to the shoreline by two gantry cranes fitted with grabs—later reduced to one crane, after the other suffered irreparable storm damage (causing the death of a crane driver) in 1940[127][128]—and was deposited into a stockpile located on a raised platform constructed of sandstone and concrete.[14]

The loading operation was highly automated for its time; it used a loading system supplied by an American company, the Mead Morrison Company. Coal fell via chutes in the base of the stockpile, into skips—of four tons capacity each—that were drawn by a continuous cable through tunnels below the stockpile and onto the loading wharf, a timber structure perpendicular to the shoreline. Thirty-three skips, running on a rail track of 20-inch gauge, were spaced along 3,200 feet (980 metres) of steel cable that moved at 3 miles/hour. The system was capable of loading ships at 700 tonnes per hour.[129]

The loader was operated by the Wallarah Coal Co.—the company that also operated the Catherine Hill Bay ocean jetty and two mechanised coal hulks on Sydney Harbour—from 1934 to 1964, when it closed for the first time. It was taken over by Coal & Allied Industries and reopened as a coal export terminal in 1967. In 1976, the cable loading system was replaced by a system of converyor belts capable of loading at 1,000 tonnes per hour.[14]

Pyrmont Coal Wharves

There were coal wharves, at Pyrmont on the western shore of Darling Harbour, where coal was sometimes unloaded[104] but, more commonly, was loaded. The Pyrmont Coal wharves were connected to the government rail system and land transport to and from these wharves was by rail. There were at least two coal cranes at Pyrmont by 1892.[130] Coal bunkering also took place at a 'coal wharf' at Pyrmont.[15]

In the 1870s, coal from Bulli was unloaded from 'sixty-milers' at Sydney and then transported by rail to the Fitzroy Iron Works at Mittagong,[104] as there was at the time no rail connection to Bulli.

The Gasworks Wharves

Australian Gas Light Company

The Australian Gaslight Company (AGL)—established in 1837—operated two gasworks. The first of these at Miller's Point opened in 1841. It fronted Darling Harbour where coal was unloaded. This plant closed in 1921.

A larger plant was opened in 1886 on a 32 hectare site at Mortlake on the Parramatta River. At full production, the Mortlake gasworks consumed nearly 460,000 tons of coal in a year, all of it delivered to its wharf by 'sixty-milers'. The Mortlake works alone needed about three 'sixty-milers' to keep it supplied.[131]

.jpg)

The original coal wharf at the Mortlake gasworks was a T-shaped structure located at the end of Breakfast Point. The unloading arrangements at Breakfast Point were that the coal was shovelled into large metal tubs by coal lumpers working inside the holds of the sixty-miler. The tubs were lifted out of the hold by cranes on the wharf—a mix of steam and electric—and transported off the wharf in rail wagons hauled by steam locomotives. Unloading a 1000-ton 'sixty-miler', in 1920, required a total of forty-nine workers per shift: five crane drivers, five tippers, five wharfmen, two locomotive drivers, two shunters, and thirty coal lumpers.[132]

From 1937, coal unloading was carried out by grab cranes on an entirely new wharf on Kendall Bay and transported from the wharf by conveyor belt, ending the dangerous and arduous—but well-paid—occupation of 'coal lumping' at Mortlake.[132]

North Shore and Manly

The North Shore Gas Company—established in 1875—operated two gasworks on the Lower North Shore. The first of these was established at Neutral Bay in 1876. The second and larger works was at Waverton and was opened in 1917. In 1937, the aging plant at Neutral Bay was closed. Both these plants had wharves for unloading coal. The Waverton plant was dominated by a massive enclosed coal store.[131]

In 1943, the gas mains of the Australian Gaslight Company and the North Shore Gas Company were interconnected to allow either company to supply the other company's customers, in case of wartime damage to one gasworks.

There was a gasworks at Little Manly Point. The operator of this gasworks, Manly Gas Company Limited, was taken over by the North Shore Gas Company in 1938, but continued to make gas at the Manly site.[133] Coal was unloaded at a wharf on the Spring Cove side of the site.[131]

Blackwattle Bay coal wharves and depots

Blackwattle Bay is an inlet lying between the Pyrmont Peninsula and Glebe Point to the east of Rozelle Bay. Blackwattle Bay was once much larger in area. The shallow part of the inlet—then known as Blackwattle Swamp—was filled in, in the late C19th, to create what is now Wentworth Park.

There were three coal depots at Blackwattle Bay, located between the reclaimed shoreline and Pyrmont Bridge Road.[134] Coal arrived by sea on 'sixty-milers' and was distributed to resellers and other customers by road transport.

The most easterly was Wharf 21, operated by Jones Brothers Coal Co.. It opened around 1926,[136] after Jones Brothers expanded their operations and relocated, from Darling Harbour at the bottom of Bathurst St.[137][138] In its final form, this installation consisted of a timber wharf—with ships berthing parallel to the shoreline—a gantry crane with a grab for unloading, and a bunker structure.[134] The first level of the bunker structure was made of concrete and brick and it had a timber superstructure as its second level. The two long edges of the bunker structure carried rails for the travelling gantry crane. It appears that the coal bunker structure and gantry crane dated from around 1951.[139]

West from Jones Brothers was R W Miller & Co.'s wharf—perpendicular to the shoreline—and further west was Wharf No. 25, the business of Howard Smith Ltd.[134] The Howard Smith coal wharf was already in operation by 1922.[140]

The area at the head of Blackwattle Bay, adjacent to the coal wharves, was used for the unloading construction aggregate—from the 'Stone Fleet' ships—and timber.

Other customers for coal on Sydney Harbour

Some industrial customers had their own wharves at which coal could be unloaded.[142] Colonial Sugar Refinery (CSR) at Pyrmont had grab cranes for unloading raw sugar in bulk, which could also be used to unload coal—from 'sixty-milers'—or other bulk cargoes when necessary. Cockatoo Island Dockyard had a coal wharf and two coal bunkers, on the south-western side of the island immediately to the north of the Sutherland Dock.[143] Coal was used as fuel by the powerhouse that supplied Cockatoo Island's electricity, including power for the dock pumps. The Nestlé chocolate factory at Abbotsford had a wharf with a coal bunker (located at the water-end) for the coal used to power its boilers.[144][145] Coal for the Balmain Power Station was landed from barges at the waterfront until 1965 [17] The Lever Brothers factory, on White Bay at Balmain landed coal as well as copra at its wharf.[141]

Coal was distributed by coal lighters (or barges); the R.W. Miller company had its origins in operation of coal lighters on Sydney Harbour. Some coal during the period from 1897 to 1931 was sourced locally from the Balmain Colliery and distributed by coal lighter.[146] The Balmain Colliery had a wharf at which ships took on bunker coal.

Botany Bay

Although far less important than Sydney Harbour as a coal port, some coal was unloaded at the 'Government Pier' (or 'Long Pier')—constructed in 1885[147]—at Botany on the northern shore of Botany Bay, near where Hill Street joins Botany Road today.[148] The coal unloaded here was for nearby industrial users. Coal for the nearby Bunnerong Power Station—opened in 1929—came by rail.[16] Botany Bay was, in those days, a shallow port with sandbanks and could only be used by smaller ships.

Decline and end of the trade

Lake Macquarie ceased to be a coal port by the 1940s. The Swansea Channel was no longer dredged after the 1930s, and could no longer be used by even the small steamships that had used Lake Macquarie as a port.[67]

The coastal coal carrying trade from the northern part of the southern coalfields ended relatively early, as the southern coalfield ocean jetties closed; the last two were the Bulli Jetty, (closed 1943) and the South Bulli Jetty at Bellambi (closed in 1952). Coal was last shipped from Wollongong Harbour in 1933.[149] The remaining coastal trade from the southern coalfields used the one remaining port, Pt Kembla, and continued until the 1960s. Pt Kembla is now a coal export port.

The demand for bunkering coal declined, as coal-fuelled steamships became less common in the 1950s and 1960s. The mechanised coal hulk, Fortuna, was converted to a coal barge in 1949. She ceased working altogether in 1953, and was towed to Putney Point and later scrapped.[113][115]

In 1949, the wharves at Pyrmont were reconstructed and coal loading operations moved to White Bay at the Balmain Coal Loader.[150]

The Ball's Head Coal Loader, which was mainly used to load bunker coal, ceased being used in 1963 and closed, for the first time, in 1964.[14] The Manly Gasworks at Little Manly Point closed in 1964.[133] Balmain Power Station closed in 1965.[17]

31 December 1971 was a critical turning point; the huge Mortlake gasworks ceased making town gas from coal. Petroleum replaced coal as a feedstock for town gas-making, and oil refinery gas was purchased to supplement supply, during the interval until Sydney's gas was converted to natural gas in December 1976.[151]

Although the Waverton gasworks site continued to be used until 1987, gas-making using coal ceased in 1969 when the plant was converted to use petroleum feedstock.[152] All town gas making operations ceased with the conversion of the North Shore to natural gas.[131] The North Shore Gas Company became 50% owned by AGL by 1974 and became a wholly owned subsidiary in 1980.

In the 1960s and 1970s there was a decline in the use of coal as hospital and industrial heating converted to other energy sources, as awareness of air pollution caused by burning black coal increased. Heavy fuel oil, a by-product of local oil refining operations in Sydney, became more available as an alternative fuel to coal for brickmaking that was cleaner-burning and less bulky to transport and store.[153] The government-owned railway network stopped using coal, once it had retired the last of its steam locomotives in 1973.[154]

From the mid-1950s through the 1960s there was a huge downturn in the coal industry, resulting in many mine closures, a number of company mergers—forming the Coal & Allied Industries group—and the rapid decline of the huge South Maitland coalfield that fed the port at Hexham. The privately-owned Richmond Vale Railway to Hexham closed in September 1987. The three coal loaders at Hexham closed in 1967, 1973 and 1988 respectively.[62] The last ship to load coal at Hexham was the MV Camira in May 1988.[155]

At Blackwattle Bay, Coal and Allied Operations Pty Ltd took over the R.W.Miller wharf, in 1960, and later bought Jones Brothers Coal Co., taking over operation Wharf 21 and its coal bunker in 1972.[136] The coal unloader, at Blackwattle Bay, closed during the 1980s, likely soon after the closure of the last loader at Hexham. Coal and Allied relinquished their lease on the Blackwattle Bay coal wharves in 1995.[136]

The 'sixty-miler' MV Stephen Brown was donated by its owners, Coal and Allied, to the Australian Maritime College in Launceston, Tasmania, in April 1983.[156]

Although local demand for coal was falling, demand in the export market increased particularly after the Oil Crises of 1973 and 1979.

In 1976, the Ball's Head Coal Loader, reopened as an export trans-shipment terminal. After 1976, most of the coal moved by the few remaining 'sixty-milers' was destined for export.[14] The last 'sixty-miler' to carry coal to Sydney—the MV Camira built in 1980[157]—ceased operating the run around 1993, with the final closure of the Ball's Head Coal Loader in that year marking the effective end of the coastal coal-carrying trade to Sydney. The MV Camira was sold in 1993 and converted to a livestock carrier.[157]

During the 1980s, the development of Newcastle as a bulk coal export port resulted in a revival of coastal coal shipping, this time to Newcastle. Purpose built in 1986, a new self-discharging collier the MV Wallarah—the fourth collier to bear the name and, at 5,717 gross tonnage, far larger than a true ‘sixty-miler’—carried coal from Catherine Hill Bay to Newcastle, where it was unloaded for export at the Port Waratah Coal Loader, Carrington. This last echo of the coastal coal-carrying trade ended on 22 July 2002.[70]

Remnants

The Dyke and the Basin are still part of the enlarged Port of Newcastle. The last of the hydraulic cranes at The Basin were demolished in 1967 to make way for a modern export coal-loader but the bases for fixed cranes 7, 8, 9 and 10 survive. The associated Carrington Pump House building still survives in Bourke St Carrington, although its equipment was removed and its chimneys demolished long ago.

Morpeth is now a picturesque riverside town; the decline of the port and other local industries has resulted in the preservation of many of its 19th-Century buildings. The wharves and most of the port's warehouses are gone.[158][159]

The Outer Harbour at Port Kembla and its breakwaters remain, as a part of an enlarged port that has a major coal export terminal—located on the newer Inner Harbour—but all the old coal jetties are gone.

All the ocean jetties are gone, except the disused jetty at Catherine Hill Bay. Also at Catherine Hill Bay is the Catherine Hill Bay Cultural Precinct, although it is now somewhat compromised by approval in 2019 of a housing development on land behind the headland where the jetty is.[160] Bushland in nearby coastal areas is protected as the Wallarah National Park.

Coalcliff jetty mine site is visible beneath the Sea Cliff Bridge.[161] Iron dowel pins that secured the timber uprights of the wharf to the bedrock and an iron mooring ring set into in the rock are all that remain of the Hicks Point Jetty at Austinmer.[94]

The last vestiges of the Bulli Jetty were a hazard to surfers and were demolished in 1988. The nearby creek, Tramway Creek, was named for the tramway linking the old Bulli Mine to the jetty.[162] All that remains of Port Bellambi is wreckage of ships. The boiler of the Munmorah can still be seen on the reef at low tide.[163][164]

Wollongong Harbour has been a fishing port, since the Illawarra Steam Navigation Company ended freight services in 1948. Belmore Basin survives including the upper-level where the coal staithes once were located, as does the concrete and iron base for the crane of the former 'Tee-Wharf'. Two cuttings, at the southern end of North Wollongong Beach, on the Tramway Shared Path, are remnants of the rail line from the Mt Pleasant Colliery that was removed in 1936.[74]

The old bridge over the Hunter River at Hexham opened in 1952 has a lifting span—no longer in use—which allowed the ‘sixty milers’ to access the one coal loader that was upstream of the bridge's location. The Stockton Bridge opened in 1971 has a 30m clearance to allow ships to use the North Channel of the Hunter River that leads to Hexham. The Hexham coal loaders are all gone. The last of the Coal & Allied facilities at Hexham—the Hexham Coal Washery—was demolished in 1989.[62]

Only a small part of the South Maitland Railway remained in use for coal traffic by 2018. A very few of the 13,000 'non-air' coal wagons and some of the steam locomotives of the northern coalfields survive at the Richmond Vale Railway Museum.The museum makes use of a short remaining part of the former Richmond Vale Railway. The NSW Rail Museum has on display two 10-ton 'non-air' four-wheel wagons; one J & A Brown wagon from the northern coalfields and one South Bulli wagon from the southern coalfields.

The former site of the coal wharves at Pyrmont on Darling Harbour is now occupied by the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Parts of the Ball's Head Coal Loader at Waverton have been converted to public space—now known as the Coal Loader Centre for Sustainability—with the derelict loading wharf remaining safely off-limits. Ships are still moored at the unloading wharf, but the ships now are ones undergoing restoration. One of the tunnels beneath the stockpile platform still has a movable chute used by the original loading system. The site has interpretive signage that provides information covering in detail the history of the site.[14]

The Blackwattle Bay coal facility and its gantry crane were largely intact, in 2002, when a master plan for the foreshore area envisaged their retention and adaptive reuse.[165] The gantry crane was demolished at some time before 2007. A partial collapse of the coal bunker occurred as a result of a downpour on 12 February 2007[166] and some of the damaged structures were demolished in 2007.

.jpg)

By September 2018, only a little of the Blackwattle Bay coal facility survived. The site is derelict and overgrown. There is a derelict brick building—the former gate-house—and one side of the coal bunker structure. The timber wharf is gone although the reclaimed land where the rest of the bunker stood remains. There are rusted remains of some coal handling equipment, including grabs and pieces of gantry crane structure. The NSW Government announced in 2016 that the Sydney Fish Markets would be relocated to the old wharf area adjoining Pyrmont Bridge Rd. That would allow the existing Fish Market site— in the shadow of the Anzac Bridge—to be redeveloped as apartment buildings.[167] Based on what is known of the plans for the site, it appears that the remainder of the old coal facility will be demolished to make way for the new Fish Market complex.[168]

The site of the old Manly Gasworks is now a public park, Little Manly Point Park.[169] The North Shore Gas Company site at Waverton is now mixed use, with some public open space and lots of apartment buildings; there are a few repurposed buildings from the old gasworks remaining (the Boiler House, the Exhauster House, the Carburetted Water Gas Plant and the chimney).[131] The Mortlake Gasworks site is now given over to housing and is known as Breakfast Point. The Gladesville Bridge, opened in 1964, was designed as a high concrete arch to allow 'sixty-milers' to reach Mortlake; it replaced an earlier bridge with an opening span.[131] The old Neutral Bay Gasworks site was used as a torpedo factory during WWII and later as a submarine base for many years, and is now in the process of being repurposed; the first stage of "Sub Base Platypus" opened in May 2018.[170] A short laneway in Millers Point—Gas Lane—is a reminder of the Miller's Point gasworks, the first in Australia.

All the foreshore industries that used coal and their coal wharves are gone, making way for residential development or repurposing. One coal bunker, the powerhouse building and its chimney remain standing on Cockatoo Island.[143]

Some piers of the old Government Pier at Botany on the northern shore of Botany Bay were still standing in 2002.[171] The area is now part of Port Botany, which has supplanted Sydney Harbour as the main cargo port of Sydney.

There is one remaining 'sixty-miler' afloat, the MV Stephen Brown, although no longer in use as a collier. She is used as a stationary training vessel by the Australian Maritime College.[172] Wrecks of other 'sixty-milers' exist at Homebush Bay in Sydney[173] and on the sea bed near Sydney.[174] The mechanised coal hulk, Muscoota, lies far from Sydney Harbour, at Discovery Bay (Waga Waga), Papua New Guinea. She still carries her last cargo of coal, but is now partially coated in coral growths—the tip of her bow above the waterline and her rudder 24 metres below—reportedly making a perfect snorkeling and dive site.[125]

References

- "The use of coal by Aboriginal people". www.coalandcommunity.com. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- Blount, Charles (1937). Memorandoms by James Martin. Copy held in National Library of Australia: The Rampant Lion Press. pp. 19, 20.

- Causer, Tim (2017). Memorandoms by James Martin - An astonishing escape from early New South Wales (PDF). UCL Press. pp. 24, 25, 82, 83, 130, 131. ISBN 9781911576815.

- "Glenrock State Recreation Area - Mining heritage and Dudley Beach fossilised forest". www.geomaps.com.au. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Collins, David (1802). An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales, Volume 2. pp. Chapter 5.

- Spooner, E.S (1938). The History and Development of Port Kembla - Paper prepared for presentation to the Engineering Conference of the Institute of Engineers Australia (30 March 1938). Copy held by National Library of Australia: NSW Department of Public Works. p. 2.

- Libraries;jurisdiction=NSW, personalName=Judy Messiter;corporateName=Community History-Lake Macquarie. "A fortunate mistake: Captain William Reid and the European discovery of Lake Macquarie". Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- "EAST GRETA COAL MINING CO., LTD". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 7 October 1921. p. 6. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Dunlop, E. W., "Lawson, William (1774–1850)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 5 April 2019

- Genders, Basil William. (21 April 1967). Coal mines in the western coalfield. [Lithgow, N.S.W.]: Lithgow District Historical Society. p. 1. ISBN 0858660032. OCLC 703558.

- Burton, G.M. (1953). "The Coal Resources of New South Wales (Draft)" (PDF). Department of National Development, Bureau of Mineral Resources Geology and Geophysics.

- NSW Dept of Primary Industry, Primefacts (February 2007). "Balmain's own coal mine" (PDF).

- "Coal lumpers | The Dictionary of Sydney". dictionaryofsydney.org. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Interpretative signage at the Ball's Head Coal Loader

- "SONOMA SAILS". Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930). 11 April 1927. p. 3. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- "THE WONDERS OF BUNNERONG". Australian Worker (Sydney, NSW : 1913 - 1950). 6 April 1932. p. 18. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Balmain Power Station | The Dictionary of Sydney". dictionaryofsydney.org. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- Royal Commission (1920). Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Design, Construction, Management, Equipment, Manning, Leading, Navigation and Running of the Vessels Engaged in the Coastal Coal-carrying Trade in New South Wales and into the Cause or Causes of the Loss of the Colliers Undola, Myola and Tuggerah. Copy held by the National Library of Australia: NSW Government Printer. pp. 1 & 2.

- "FLOTILLA AUSTRALIA". www.flotilla-australia.com. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- 1934-, Rogers, Brian (1984). S.S. Undola : a collier in the Illawarra trade. University of Wollongong. Faculty of Education. [Wollongong]: Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong. ISBN 0864180020. OCLC 27593592.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Atchison, John, "Miller, Robert William (1879–1958)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 22 September 2018

- "FLOTILLA AUSTRALIA". www.flotilla-australia.com. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- 1933-, Turner, J. W. (John William) (1982). Coal mining in Newcastle, 1801–1900. Newcastle, N.S.W., Australia: Newcastle Region Public Library, Council of the City of Newcastle. pp. 133, 134. ISBN 0959938591. OCLC 12585143.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- 1933-, Turner, J. W. (John William) (1982). Coal mining in Newcastle, 1801–1900. Newcastle, N.S.W., Australia: Newcastle Region Public Library, Council of the City of Newcastle. pp. 85, 100 & 112. ISBN 0959938591. OCLC 12585143.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Kenn., Pearce (1994). Coals to Hexham : the continuing story. McNicol, Steve. ([Rev. ed.] ed.). Elizabeth, S. Aust.: Railmac Publication. p. 19. ISBN 0949817961. OCLC 38356828.

- "MINING RESOURCES". Illustrated Sydney News and New South Wales Agriculturalist and Grazier (NSW : 1872 - 1881). 23 March 1878. p. 13. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- 1933-, Turner, J. W. (John William) (1982). Coal mining in Newcastle, 1801–1900. Newcastle, N.S.W., Australia: Newcastle Region Public Library, Council of the City of Newcastle. pp. 62, 63. ISBN 0959938591. OCLC 12585143.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Chart of Newcastle Harbour and Port Waratah [cartographic material]". nla.gov.au. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "NEWCASTLE REGION - SHIPWRECKS". oceans1.customer.netspace.net.au. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "THE OYSTER BANK". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 19 July 1932. p. 4. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "The ship Yarra Yarra (1851-1877): a Stockton Oyster Bank victim | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "The Dreaded Oyster Bank". Newcastle Sun (NSW : 1918 - 1954). 8 September 1947. p. 16. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "EXTENSION OF BREAKWATERS". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 24 April 1907. p. 10. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "NEWCASTLE'S HANDICAP". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 16 June 1920. p. 5. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ""SHOOTING" THE BAR". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 12 September 1929. p. 12. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "NEW CHANNEL ON THE BAR". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 29 July 1932. p. 8. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "THE HARBOR BAR HANDICAP". Newcastle Sun (NSW : 1918 - 1954). 3 April 1934. p. 6. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "EARLY NEWCASTLE". Newcastle Sun (NSW : 1918 - 1954). 19 November 1926. p. 6. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "HARBOUR WORKS AT NEWCASTLE". Sydney Mail (NSW : 1860 - 1871). 5 June 1869. p. 13. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "KEY TO THE VIEW OF NEWCASTLE". Illustrated Sydney News and New South Wales Agriculturalist and Grazier (NSW : 1872 - 1881). 8 April 1875. p. 20. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Queens Wharf, Newcastle, in 1882". Newcastle Sun (NSW : 1918 - 1954). 19 November 1926. p. 1. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Hunter Estuary".

- "Ship News". Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842). 13 February 1838. p. 2. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "MORPETH COAL SHOOTS". New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 - 1900). 26 July 1864. p. 1684. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "VISIT TO MORPETH". Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 - 1893). 10 February 1866. p. 4. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "SHIPPING COAL AT MORPETH". Miners' Advocate and Northumberland Recorder (Newcastle, NSW : 1873 - 1876). 3 October 1874. p. 3. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "The Morpeth Coal Staiths". Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931). 16 June 1877. p. 4. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "THE MORPETH COAL SHOOTS". Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930). 18 November 1887. p. 5. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "WHARF ACCOMMODATION AT MORPETH". Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930). 19 August 1910. p. 10. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "MAITLAND AND MORPETH RAILWAY". Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News (NSW : 1859 - 1866). 12 March 1864. p. 2. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "DEEPENING THE RIVER". Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW : 1894 - 1939). 18 November 1929. p. 2. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "THE MORPETH COAL SHOOTS". Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW : 1894 - 1939). 28 December 1907. p. 4. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "MORPETH SHIPPING TO CEASE". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 9 July 1931. p. 6. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "The newcastle Scene". Newcastle Sun (NSW : 1918 - 1954). 23 July 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "ROTHBURY COAL". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 27 April 1940. p. 9. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "SOIL EROSION IN UPPER HUNTER". Muswellbrook Chronicle (NSW : 1898 - 1955). 26 August 1941. p. 1. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "A BOMSHELL!". Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW : 1894 - 1939). 9 July 1931. p. 6. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Morpeth Line To Close". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 27 May 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Last Journey For "Little Train"". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 29 August 1953. p. 2. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Kingswell, George H. (1890). The Coal Mines of Newcastle, NSW - Their Rise and Progress. https://downloads.newcastle.edu.au/library/cultural%20collections/pdf/The_coal_mines_of_Newcastle_NSW_their_rise_and_progress.pdf. p. 4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "NEW COAL LOADING PLANT AT HEXHAM". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954). 25 January 1936. p. 7. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Help with defunct NSW branch at Hexham". Railpage. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "Old sea tales of the 'sixty-milers'". Newcastle Herald. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "THE S.S. NOVELTY". Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930). 1 November 1912. p. 13. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "THE STEAMER COMMONWEALTH FOUNDERS". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List (Sydney, NSW : 1891 - 1954). 21 August 1916. p. 4. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "COLLIER RUNS AGROUND". Evening News (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1924 - 1941). 13 January 1938. p. 6. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- MeEwan, Fiona. "Regional History Research Paper: Green Point-Belmont" (PDF).

- "Advertising". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List (Sydney, NSW : 1891 - 1954). 29 April 1910. p. 1. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Wallarah Jetty, Catherine Hill Bay". www.records.nsw.gov.au. 16 August 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Clark, Mary Shelley (August 2002). "Shipping Out - Wallarah's Last Run" (PDF). Afloat.

- Spooner, E.S (1938). The History and Development of Port Kembla - Paper prepared for presentation to the Engineering Conference of the Institute of Engineers Australia (30 March 1938). Copy held by the National Library of Australia: NSW Department of Public Works. p. 7.

- 1934-, Rogers, Brian (1984). S.S. Undola : a collier in the Illawarra trade. University of Wollongong. Faculty of Education. [Wollongong]: Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong. pp. 7, 8 & 9. ISBN 0864180020. OCLC 27593592.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Advertising". Illustrated Sydney News (NSW : 1881 - 1894). 15 October 1887. p. 1. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- Interpretive sinage at Wollongong Harbour and Tramway Shared Path

- Spooner, E.S. (1938). The History and Development of Port Kembla - Paper prepared for presentation to the Engineering Conference of the Institute of Engineers Australia (30 March 1938). Copy held by the National Library of Australia: NSW Department of Public Works. p. 6.

- Bellambi Coal Co. Limited (1909). The Mines of the Bellambi Coal Co. Limited. Bellambi Coal Co. Limited.

- "South Bulli Colliery". Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931). 15 November 1887. p. 4. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Opening of the South Bulli Coal Company's Mine". Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912). 19 November 1887. p. 1100. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "OPENING OF THE SOUTH BULLI COAL COMPANY'S MINE". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 14 November 1887. p. 8. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Corrimal History". 19 September 2006. Archived from the original on 19 September 2006. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "DAMAGE TO THE BELLAMBI JETTY". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 15 February 1898. p. 5. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Eardley, Gifford. Transporting the Black Diamond - Book 1. Canberra: Traction Publications. p. 47.

- "Industrial history Mining metallurgy illawarra heritage trail - The Jetty at Bellambi Harbour". www.illawarra-heritage-trail.com.au. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "RECORD COAL LOADING". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 10 July 1909. p. 13. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Bellambi Point - Beach in East Corrimal Wollongong NSW". SLS Beachsafe. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Shipwrecks Bellambi" (PDF).

- "Glass plate negative, full plate, 'Coalcliff Jetty', Kerry and Co, Sydney, Australia, c. 1884-1917". collection.maas.museum. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Brian, Rogers (1975). "Shipping operations at Coal Cliff, 1877–1910". Research Online.

- "Coal-cliff Coal Mining Company". Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW : 1856 - 1950). 25 September 1877. p. 2. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- 1934-, Rogers, Brian (1984). S.S. Undola : a collier in the Illawarra trade. University of Wollongong. Faculty of Education. [Wollongong]: Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong. p. 7. ISBN 0864180020. OCLC 27593592.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "BULLI". Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW : 1856 - 1950). 7 June 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- 1934-, Rogers, Brian (1984). S.S. Undola : a collier in the Illawarra trade. University of Wollongong. Faculty of Education. [Wollongong]: Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong. pp. 54, 55. ISBN 0864180020. OCLC 27593592.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Glass plate negative, entitled 'The jetty, Austinmer', depicting the coal loading wharf at Austinmer, New South Wales, full plate, glass / silver gelatin, photograph by Kerry and Co, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 1880s, part of Tyrrell Collection". collection.maas.museum. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Industrial history Mining metallurgy illawarra heritage trail - Hicks Point Jetty". www.illawarra-heritage-trail.com.au. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Map of rail connections to Hicks Point Jetty".

- Kerle, H. W. (9 June 1887). "Ocean Jetty". Minutes of Proceedings of the Engineering Association of New South Wales. 2.

- Eardley, Gifford (1968). Transporting the Black Diamond - Book 1. National Library of Australia: Traction Publications. p. 71.

- "PANORAMA HOTEL DAMAGED". Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW : 1856 - 1950). 21 May 1943. p. 1. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "STORM DAMAGE AT PORT KEMBLA ESTIMATED AT £100,000". Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW : 1856 - 1950). 15 June 1945. p. 7. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "JETTY COLLAPSES". South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (NSW : 1900 - 1954). 10 February 1949. p. 1. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "Jetty Falls Into Sea; Four Men Stranded". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 7 February 1949. p. 1. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "The Demise of Bulli Jetty". Looking Back. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ""60-Milers" Rush Coal To City". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 28 January 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 30 September 2018.