China containment policy

The China containment policy is a political term referring to the alleged goal of U.S. foreign policy in the past or present to diminish the economic and political growth of the People’s Republic of China. The term harkens back to the U.S. containment policy against communist countries during the Cold War.

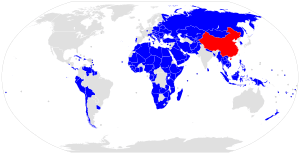

The theory asserts that the United States needs a weak, divided China to continue its hegemony in Asia. This multifaceted strategy is accomplished by the United States establishing military, economic, and diplomatic ties with countries adjacent to China's borders, frustrating China's own attempts at alliance-building and economic partnership, and the utilization of tariffs, sanctions and lawfare. The presence of American military in Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, Philippines;[1] recently strengthened ties with South Korea[2] and Japan;[3] efforts to improve relations with India[4] and Vietnam;[2] and the Obama administration's 2012 Pivot to Asia Strategy for increased American involvement in the Pacific have been pointed to as evidence of a current containment policy. The United States had formerly claimed it had no China containment policy and that they "want China to succeed and prosper."[5]

The US has made efforts to contain China in the past however through military actions undertaken in the Vietnam War as evidenced in the leaked Pentagon Papers. President Richard Nixon’s China rapprochement signaled a temporary shift in focus to gain leverage in containing the Soviet Union. That position changed in 2019 when the US State Department Director of Policy Planning, Kiron Skinner revealed details of a study detailing a containment strategy for China that is said to be influenced by the book Clash of Civilizations by Samuel Huntington.

Justifications

Cold War era

During the Cold War the United States tried to prevent the domino theory spreading of communism and thwart communist countries including that of the PRC. Revelations about the overt and ulterior motives behind the US intervention in Vietnam and the covert widening of combat operations to nearby Cambodia and Laos was leaked in the Pentagon Papers by Daniel Ellsberg in 1971.[6]

Although President Lyndon B. Johnson stated that the aim of the Vietnam War was to secure an "independent, non-Communist South Vietnam", a January 1965 memorandum by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara stated that an underlying justification was "not to help a friend, but to contain China".[7][8]

McNamara accused China of harboring imperial aspirations like those of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. According to McNamara, the Chinese were conspiring to "organize all of Asia" against the United States.[9]

.jpg)

As laid out by U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, the Chinese containment policy of the United States was a long-run strategic effort to surround Beijing with the USSR, its satellite states, as well as:

a) The Japan–Korea front,

b) The India–Pakistan front, and

c) The Southeast Asia front

Post-Cold War

In more contemporary times after the Nixon rapprochement and collapse of the USSR, the US and China enjoyed a period of closer economic ties and outwardly warmer relations.

The US 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review Report stated that China has "the greatest potential of any nation to militarily compete with the US and field disruptive military technologies that over time offset traditional US advantages."[10] The document continues by stating that China must be more open in reporting its military expenditures and refrain from "locking up" energy supplies by continuing to obtain energy contracts with disreputable regimes in Africa and Central Asia.[11] The policy assumes that measures should be taken against China to prevent it from seeking hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region and/or worldwide.[12]

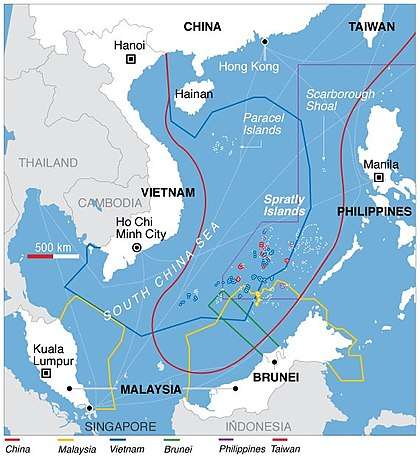

The United States’ political leadership began to openly embrace containment policies in 2011, starting with President Barack Obama’s “pivot” toward Asia, which was supposed to involve a winding down of the War in Iraq and withdrawal of troops and military assets in the Middle East and Persian Gulf region and redeploying them in the Asia-Pacific; the Chinese leadership were keen to this “pivot” as a new Cold War era containment strategy and attempted to open a dialogue regarding the US concerns about the South China Sea but they were rebuffed.[13] Supporters of Chinese containment or increased American involvement in East Asia have cited the United States as a counterbalance to the excesses of Chinese expansion. Countries in territorial disputes with China, such as in the South China Sea and the Senkaku Islands, have complained about harassment in the disputed areas.[14][15][16][17] Some experts have suggested that China may leverage their economic strength in such disputes, one example being the sudden restriction on Chinese imports of Filipino bananas during tensions over the Scarborough Shoal.[18]

Formalization and implementation

President Trump and his administration have revealed details about a long term strategy in dealing with the rise of China. A study on China produced by a small working group within the US State Department led by Kiron Skinner reportedly envisions a world of unavoidable and aggressive great power competition and a “clash of civilizations”.[19][20] The study was informally called “Letter X” in reference to the X Article that advocated for a containment strategy for the Soviet Union.[20] In a speech at the Future Security Forum on April 29, 2019, Skinner, the Director of Policy Planning, characterized the Cold War as “a huge fight within the Western family” and due to that shared heritage and value-system, breakthroughs could be made; on China however, she argued there can be no accommodation or cooperation because it is “...a fight with a really different civilization and a different ideology” and “it’s the first time that we will have a great-power competitor that is not Caucasian.”[19] To what extent this controversial and much criticized viewing of foreign policy in a racialized lens will be carried out in practice as official policy within the US State Department is yet to be seen. Trump has repeatedly spoken publicly about thawing relations with Russia and has reportedly made overtures with Russian officials in an attempt to recruit Russia as a strategic foil to help contain China.[21][22] An open letter was released by China-focused scholars, foreign policy experts and business leaders that decried the new adversarial approach as counterproductive and urged the administration to continue the more cooperative approach.[23]

The new policy has been buttressed to some extent by US-led multinational organizations, NGOs and think tanks. In April 2019, the fourth iteration of the influential neoconservative think tank, the Committee on the Present Danger was unveiled, calling itself the “Committee on the Present Danger: China (CPDC)” in a press conference in Washington, DC.[24] The organization was reformed by former Trump administration White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon and former Reagan administration official, Frank Gaffney to “educate and inform American citizens and policymakers about the existential threats presented from the Peoples Republic of China under the misrule of the Chinese Communist Party.”[22] The CPDC takes the view that there is “no hope of coexistence with China as long as the Communist Party governs the country.”[24] This good vs. evil false dilemma ideological framing of future US-China relations begets some criticism in the foreign relations community as overly hawkish, arguing it similar to the fear-mongering that led to the Red Scare under Senator Joseph McCarthy and hysteria that led to disastrous wars in Vietnam and Iraq. Charles W. Freeman Jr. at the Watson Institute called the CPDC “a who’s who of contemporary wing-nuts, very few of whom have any expertise at all about China and most of whom represent ideological causes only peripherally connected to it."[22]

With questions about the continued purpose of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in a post Cold War world, NATO countries have refrained from re-orienting toward and labeling the PRC an outright “enemy”, but NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg said the organization needs to recognize the “challenges” posed by China at a NATO event in 2019, saying "China will soon have the world's biggest economy. And it already has the second largest defense budget, investing heavily in new capabilities”[25] and also said that NATO did not want to “create new adversaries”; this contrasted with the United States’ NATO representative at the event, who referred to China as a “competitor”.[26]

Military strategy

The United States’ Indo-Pacific strategy has broadly been to use the surrounding countries around China to blunt its influence. This includes strengthening the bonds between South Korea and Japan[27] as well as trying to get India, another large developing country to help with their efforts.[28] Additionally, with the US withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia (in part because China wasn’t a party to it), the US has reportedly wanted to find a host in the Asia-Pacific region to point the previously banned weapons at China.[29] In addition to soft power diplomacy within the region, the US is physically surrounding China with military bases in the event of any conflict.[30] The United States has developed many military bases in the Asia Pacific equipped with warships, nukes, and nuclear-capable bombers as a deterrent and to achieve full spectrum dominance in a strategy similar to that of the Cold War.[31]

Lawfare and sanctions

The use of economic sanctions has always been a tool of American foreign policy and has become used more frequently in the 21st century, from targeting individuals and sometimes whole countries by using the centrality of the US financial system and the position of the dollar as the world's reserve currency to limit trade and cashflow.[32]

Xinjiang

In the human rights arena, the United States and the Trump administration has worked to isolate China internationally by drawing attention to its human rights record. In particular US policymakers have focused on the status of China’s “re-education camps” for those accused of religious extremism in China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region, the region inhabited by the Uyghur Muslim minority as well as the protests in Hong Kong.[33] These camps, which some NGOs estimate have a population of over one million people, have been described as “indoctrination camps” that are reportedly run like prisons to eradicate Uyghur culture and religion in an attempt at Sinicization[34] as well as likened to concentration camps in the early days of Nazi Germany.[35] The United States Congress has responded to these reports with calls for the imposition of sanctions under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act; in December of 2019, the House of Representatives and Senate passed the Uighur Human Rights Policy Act.[36] Chinese officials have responded to the criticism and scrutiny by rejecting the “more than one million” camp population estimate by foreign experts and say the “vocational education centers” in Xinjiang are for preventing religious extremism by teaching Mandarin and job skills and cast doubt on the reports as “maliciously distorting and slandering” China’s counter-terrorism and de-radicalization efforts.[34] At an event at the U.N. Human Rights Council session in Geneva, a spokesperson at China’s Bureau of Human Rights Affairs of the State Council Information Office told reporters that “if you do not say it’s the best way, maybe it’s the necessary way to deal with Islamic or religious extremism, because the West has failed in doing so, in dealing with religious Islamic extremism”, and dismissed the view that Xinjiang’s surveillance create a martial law environment, saying “As to surveillance, China is learning from the UK...your per capita CCTV is much higher than that for China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region.”[37]

Hong Kong

As has been the case in the past with other adversarial countries, some pro-Chinese commentators argue that the US has allegedly taken advantage of cleavages and regionalism within the PRC and the One Country Two Systems framework to Divide and conquer, particularly in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong through the promotion of western democratic institutions. They criticized "US meddling in domestic affairs" when a controversial extradition bill was introduced in the Hong Kong SAR, sparking the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Beijing accused the US of domestic interference by allegedly backing a particularly violent contingent of protesters wearing black masks through the government funded National Endowment for Democracy. Although the US denies the allegations of interference, pro-Chinese elements nevertheless maintained such view, stating that US diplomats have been photographed meeting with the protesters and lawmakers have hosted multiple protest leaders in Washington and voiced public support for the protesters' demands, and saying that the "One-Country, Two-Systems" arrangement should be honored.[38][39][40][41]

Economic strategy

With China entering the World Trade Organization in 2001 with approval from the US, China and the world economy benefited from globalization and the access to new markets and the increased trade that resulted. Despite this, some in the United States lament letting China in the WTO because part of the motivation to do so, the political liberalization of the PRC’s government along the lines of the Washington Consensus never materialized. The US hoped economic liberalization would eventually lead to political liberalization to a government more akin to the then recently repatriated Hong Kong Special Administrative Region under One country, two systems.[42]

Trans Pacific Partnership

In part, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), geopolitically was thought by some to likely bring China's neighbours closer to the United States and reduce its economic leverage and dependence on Chinese trade.[43][44][45][46][47][48][49] If ratified, the TPP would have strengthened American influence on future rules for the global economy. US Secretary of Defense Ash Carter claimed the passage of the TPP to be as valuable to the United States as the creation of another aircraft carrier.[50] President Obama has argued "if we don't pass this agreement—if America doesn't write those rules—then countries like China will".[51]

President Donald Trump formally withdrew the United States from the Trans Pacific Partnership in 2017.

Trade War

.jpg)

In what would become the China–United States trade war, President Donald Trump in 2018 began setting tariffs and other trade barriers on China with the goal of forcing it to make changes to what the U.S. says are "unfair trade practices".[52] The US says those trade practices and their effects are the growing trade deficit, the theft of intellectual property, and the forced transfer of American technology to China.[53] Some see hypocrisy in this characterization and instead posit that the allegations are exaggerated and China is pursuing economic development much in the same way many other modern industrialized economies have before it, except in a world where the rules of the global free trade order, developed, governed, and backed by the US and other developed western multilateral institutions (World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization), favors already developed countries, making development difficult or inimitable.[54] At the Bretton Woods Conference, the US representative, Harry Dexter White, insisted that the world reserve currency be the United States dollar instead of a proposed new international unit of currency and that the IMF and World Bank be under the purview of the United States.[55] The Reagan administration and US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and Trump as a private citizen made identical claims in the 1980s when Japan was undergoing its economic miracle which led Japan to signing the Plaza Accord.[56] Like the TPP, it has been argued that the trade war is simply a more direct attempt to stifle China's development and is indicative of a shift in the US public perception of China as a "rival nation to be contained and beaten" among the two major political parties in Congress, the general public and even the business sector.[57] It has been argued however that employing the Cold War playbook for the seemingly destined to fail Soviet Union, a state-run and largely closed economy will not work in the case of China because of its sheer size, growing wealth, and vibrant economy.[58] To halt development progress, particularly the Made in China 2025 plan, the US has responded by making it harder for Chinese tech companies from obtaining US technologies or investing in or acquiring US tech companies, and even attempting to stifle specific companies, namely Huawei and ZTE from doing business domestically and abroad allegedly due to unspecified or speculative national security risks.[59][55] With senior Trump administration officials such as John Bolton, Peter Navarro and Robert Lightizer demanding any comprehensive trade deal feature “structural changes” which would essentially entail China surrendering its sovereignty over its economic system and planning (its Made in China 2025 industrial plan) and permanently ceding technology leadership to the US-an untenable situation to the Chinese- some see trade tensions continuing long into the future.[55]

In the face of the US tariffs in the trade war and the sanctions on Russia following the annexation of Crimea, China and Russia have cultivated closer economic ties as well as security and defense cooperation to offset the losses.[60][61][62]

Belt and Road Initiative

Another high profile dispute among the US and the PRC on the international stage is the United States alarm about China’s growing geopolitical footprint in soft power diplomacy and international finance and trade. Particularly, this surrounds China’s Belt and Road Initiative (formerly One Belt, One Road) which the Trump administration in particular as well as those in western media have labeled the initiative as “aggressive” “debt trap diplomacy” and pointed to the sale of an interest in a long term lease by Sri Lanka in the Port of Hambantota to a Chinese state owned company after Sri Lanka had defaulted on a loan to develop the port.[63]

Where others in the Anglosphere see malice and deceit in the BRI, others, while admitting it is not altruistic in nature, is peacefully pursuing economic interests and mutually beneficial trade ties for the procurement of resources and market access for its export-driven economy. In this perspective, China is utilizing and selling the expertise it has gained in poverty alleviation and infrastructure building used in its own journey to modernization to other developing countries.[64][65] Additionally, a study conducted by the Rhodium Group had found only one case of asset seizure, the oft-cited Hambantota port in Sri Lanka and the PRC is more likely to restructure or write-off the debt.[66]

The BRI has been a largely well received and long awaited alternative to developing countries that the US and other western development banks have long neglected due to either slow investment returns or the imposition of what some recipient governments would see as onerous demands regarding political liberalization, transparency, and human rights. Proponents of this line of thought dismiss claims of “debt trap diplomacy” as hypocritical and is propagandizing the initiative to disrupt the economic interests and peaceful rise of the PRC on the world stage.[67]

Strategic alliances

US–India

It is assumed that it was established or reconfirmed during President George W. Bush’s visit to India in March 2006. The media speculated about India–United States relations having the US use India to contain China. Indian officials publicly denied the claims.[68][69]

US–Japan–Australia

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice visited Australia in March 2006 for the "trilateral security forum" with the Japanese foreign minister Taro Aso and his Australian counterpart Alexander Downer.[70][71] (See Japan–United States relations and Australia–United States relations) Labeled by the Asian media as a "little NATO against China" or the new "triple alliance", or "the axis of democracy" by the Economist.[72]

Japan–Australia

(See Australia–Japan relations.) On March 15, 2007, both nations signed a strategic military partnership agreement,[73] which analysts believe is aimed at alienating China.[74]

US–Japan–Australia–India

In May 2007, the four nations signed a strategic military partnership agreement, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

US–Japan–India

The three nations held their first trilateral meeting in Dec 2011.[75]

Japan–Australia–India

The three nations held their first trilateral meeting in June 2015.[76]

US– Taiwan

Although the United States recognized the People’s Republic of China in 1979, the US maintains de facto diplomatic relations and is bound to it by the Taiwan Relations Act, which ambiguously states, “the United States will make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capabilities".

The recent decade has seen an increasing frequency of US arms sales to Taiwan alongside expanding commercial ties. On December 16, 2015, the Obama administration announced a deal to sell $1.83 billion worth of arms to the Armed Forces of Taiwan, a year and eight months after U.S. Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act Affirmation and Naval Vessel Transfer Act of 2014 to allow the sale of Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates to Taiwan. The deal would include the sale of two decommissioned U.S. Navy frigates, anti-tank missiles, Assault Amphibious Vehicles, and FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missiles, amid the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. A new $250 million compound for the American Institute in Taiwan was unveiled in June 2018, accompanied by a "low-key" American delegation. The Chinese authorities denounced this action as violation of the "one China" policy statement and demanded the USA stop all relations with Taiwan without intercession of China. In 2019, the US approved the sale of 108 M1A2 Abrams tanks and 250 Stinger missiles for $2.2 billion and 66 F-16V fighter jets for $8 million. With such a large sale, China vowed to sanction any companies involved in the transactions.[77]

US–Philippines

The relationship between the United States and the Philippines has historically been strong and has been described as a Special Relationship. The 1951 mutual-defense treaty was reaffirmed with the November 2011 Manila Declaration.

US–South Korea

_interceptors_is_launched_during_a_successful_intercept_test_-_US_Army.jpg)

The US continues to host military bases in South Korea. The Chinese believe the deployment of the US made Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system on the peninsula is not for the stated purpose of protecting against a nuclear armed North Korea, but to degrade the PLA Rocket Force from carrying out a nuclear second strike in the event of a war with the United States.[78] South Korea’s decision to deploy the system led to a significant deterioration in China–South Korea relations

Challenges

Australia

Australia has a growing dependency on China’s market. Its mining industry is booming owing to Chinese demand.[79] During the second Bush Administration, ahead of the visit by Condoleezza Rice and her warning about China becoming a "negative force"[80] the Australian Foreign Affairs Minister, Alexander Downer, warned that Australia does not agree with a policy of containment of China.[81] Rice clarified that the U.S. is not advocating a containment policy.

India

India is a founding member of the Non Aligned Movement, a group of mostly developing states that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc which has among its five pillars “mutual non-aggression”, “mutual non-interference in domestic affairs, and “peaceful co-existence”. The basis of the Non Aligned Movement is based on the principles in a 1954 agreement on China–India relations, the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.

China is India's largest trading partner.[82] George W. Bush’s visit to India was seen in part as an attempt to boost bilateral trade and to expand US influence, by offering India important nuclear technology. China is the US's fifth-largest trading partner in terms of exports, but India ranks only twenty-fourth.[83]

Japan

China has overtaken the U.S. as Japan’s largest trading partner.[84]

Philippines

Under President Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippines has cultivated closer ties to China and has tried to compartmentalize the South China Sea territorial issues from the broader relationship. In a speech in July of 2019, President Duterte claimed that the United States has been trying to use the Philippines as “bait” to ignite regional conflict and confrontation with China regarding incidents in the South China Sea, “egging“ him to take military action against China and pledging US support through the mutual defense obligations. To this idea he sarcastically said “if America wants China to leave, and I can't make them...I want the whole 7th Fleet of the armed forces of the United States of America there...when they enter the South China Sea, I will enter.” He added, “what do you think Filipinos are, earthworms?...now, I say, you bring your planes, your boats to South China Sea. Fire the first shot, and we are just here behind you. Go ahead, let's fight."[85]

South Korea

China is South Korea's biggest trading partner, with trade with China making up 25.1% of its exports and 20.5% of its imports.[86]

See also

- Chinese century

- China-United States relations

- America's Pivot to Asia Strategy

- Geostrategy in Central Asia

- Quadrilateral Security Dialogue

- Second Cold War

- AirSea Battle

- Blue Team (U.S. politics)

- Philippines–United States relations

- India-United States relations

- Japan-United States relations

References

- Lam, Willy (22 April 2002). "China opposes U.S. presence in Central Asia". China Daily. CNN. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Carpenter, Ted (30 November 2011). "Washington's Clumsy China Containment Policy". The National Interest. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Jinan, Wu (25 January 2013). "Containment of China Is Abe's Top Target". China-United States Exchange Foundation. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Will India join strategic containment of China?". People's Daily. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Daozu, Bao (11 November 2010). "US denies China 'containment'". China Daily. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-465-04195-4.

- "COVER STORY: Pentagon Papers: The Secret War". CNN. June 28, 1971. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- "The Nation: Pentagon Papers: The Secret War". Time. June 28, 1971. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- Robert McNamara (November 3, 1965). "Draft Memorandum From Secretary of Defense McNamara to President Johnson". Office of the Historian.

- Hawkins, William R (June 2, 2007). The dangers in talking to China. Asia Times Online.

- Bush, George (March 2006). The National Security Strategy of the United States of America. The White House.

- Feng, Huiyun (2007). Chinese strategic culture and foreign policy decision-making: Confucianism, leadership and war. Routledge. p.81. ISBN 978-0-415-41815-7.

- Goodman, Melvin (June 13, 2019). "The Twin Dangers of Exceptionalism and Mindless Bi-Partisanship". CounterPunch. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Blumenthal, Daniel (15 April 2011). "Riding a tiger: China's resurging foreign policy aggression". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Japan protest over China ship's radar action". BBC News. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "China and Vietnam in row over detention of fishermen". BBC News. 22 March 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Page, Jeremy (3 December 2012). "Vietnam Accuses Chinese Ships". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Higgins, Andrew (10 June 2012). "In Philippines, banana growers feel effect of South China Sea dispute". Washington Post. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Musgrave, Paul (May 2, 2019). "The Slip That Revealed the Real Trump Doctrine". Foreign Policy. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Sanger, David E. (August 2, 2019). "State Dept. Officials Force Out Top Policy Planner and Adviser to Mike Pompeo". New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Gabuev, Alexander (May 24, 2017). "Donald Trump's plan to play Russia against China is a fool's errand". South China Morning Post. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Carden, James (August 5, 2019). "Steve Bannon's Foreign Policy Crusade Against China". The Nation. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Albert, Eleanor (July 19, 2019). "The US-China Relationship: Why Words Matter". The Diplomat. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Skidmore, David (July 23, 2019). "The US Scare Campaign Against China". The Diplomat. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Griffiths, James (December 4, 2019). "A challenge from China could be just the thing to pull NATO together". CNN. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Holly Ellyatt and David Reid (December 3, 2019). "China's military might has now become a top issue for NATO". CNBC. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Mehta, Aaron (August 15, 2019). "Tension between South Korea and Japan could hurt US goals in the Pacific — and China is watching". DefenseNews. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Zhou, Laura (June 5, 2018). "Indian leader Modi wants no part of China-US rivalry, but still manages to keep Beijing happy". South China Morning Post. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Peck, Michael (August 18, 2019). "100 Billion Reasons Why: Why Australia Said No to American Missiles Aimed At China". The National Interest. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Reed, John (August 20, 2013). "Surrounded: How the U.S. Is Encircling China with Military Bases". Foreign Policy. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Reed, John (August 20, 2013). "Surrounded: How the U.S. Is Encircling China with Military Bases". Foreign Policy. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Gilsinan, Kathy (May 3, 2019). "A Boom Time for U.S. Sanctions". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Wong, Edward (December 27, 2019). "Congress Wants to Force Trump's Hand on Human Rights in China and Beyond". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ”AT CONTRIBUTOR” (December 9, 2019). "China defends its Xinjiang 're-education' camps". Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- McLoughlin, Bill (December 31, 2019). "China's Muslim clampdown: Beijing's re-education camps likened to 1989 Tiananmen massacre". Express. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Flatley, Daniel (December 3, 2019). "U.S. House Passes Xinjiang Bill, Prompting Threat From China". Bloomberg. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Miles, Tom (September 13, 2018). "Chinese official says China is educating, not mistreating, Muslims". Reuters. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- SCMP Reporters (October 13, 2019). "As it happened: policeman slashed in the neck amid citywide protests in Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Carpenter, Ted Galen (September 12, 2019). "US meddling in Hong Kong could trigger a tragedy". The Hill. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Escobar, Pepe (October 8, 2019). "Tracking foreign interference in Hong Kong". Asia Times. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "Hong Kong's Joshua Wong heads to Washington to seek US support".

- Pethokoukis, James (September 5, 2019). "What if the global economy had stayed closed to China?". American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "What Will the TPP Mean for China?". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Perlez, Jane (6 October 2015). "U.S. Allies See Trans-Pacific Partnership as a Check on China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "Trade Is a National Security Imperative - Harvard - Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs". belfercenter.hks.harvard.edu. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Boot, Max (2016-04-29). "The Geopolitical Necessity of Trade".

- Magnusson, Earl Anthony Wayne, Oliver. "The Death of TPP: The Best Thing That Ever Happened to China". The National Interest. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- "This Isn't Realpolitik. This Is Amateur Hour". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- "Trump Will Be Haunted by the Ghost of TPP". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- Green, Michael J.; Goodman, Matthew P. (2 October 2015). "After TPP: the Geopolitics of Asia and the Pacific". The Washington Quarterly. 38 (4): 19–34. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2015.1125827. ISSN 0163-660X.

- Calmes, Jackie (5 November 2015). "Trans-Pacific Partnership Text Released, Waving Green Flag for Debate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Swanson, Ana (July 5, 2018). "Trump's Trade War With China Is Officially Underway". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "Findings of the Investigation into China's Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation Under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974" (PDF). Office of the United States Trade Representative. March 22, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Spross, Jeff (April 12, 2019). "China isn't cheating at trade. It's just running America's old plays". The Week. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "Why the US-China trade war might not end". 18 February 2019.

- Griffiths, James (May 24, 2019). "The US won a trade war against Japan. But China is a whole new ball game". CNN. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Yuwen, Deng (July 4, 2018). "The US sees the trade war as a tactic to contain China. So does Beijing". South China Morning Post. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Saetren, Will (September 17, 2018). "US cold war containment strategy against China may not end the Soviet way. Instead, it could explode into armed conflict". South China Morning Post. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Kharpal, Arjun (September 29, 2019). "China's tech ambition is 'unstoppable' — with or without the trade war, analyst says". CNBC. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "US trade war makes Russia an indispensable partner for China". 2019-05-14.

- "Sanctions encourage Sino-Russian cooperation". 2019-12-11.

- "China and Russia are getting along better than ever, the U.S. Has only made it easier for them". 2019-08-07.

- Thomas P. Cavanna (July 2019). "Unlocking the Gates of Eurasia: China's Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications for U.S. Grand Strategy". Texas National Security Review. 2 (3).

- Dodwell, David (April 21, 2019). "Turning China's Belt and Road Initiative into a new cold war weapon by the US is deeply frustrating". South China Morning Post. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Mardell, Jacob (May 1, 2019). "China's Belt and Road Partners Aren't Fools". Foreign Policy. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Zhou, Laura (April 30, 2019). "Why China's belt and road loans may not be the debt trap other countries fear". South China Morning Post. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Li Shipeng and Zheng Dongchao (April 4, 2019). "The Belt and Road Initiative does not lay debt traps". The Telegraph. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Nuclear deal no threat to China, Pak: Narayanan Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. March 2006. Online News.

- Gilani, Iftikhar (March 18, 2006). "US-India N-deal should not threaten Pakistan, China". Daily Times.

- Jain, Purnendra (March 18, 2006). "A 'little NATO' against China". Asia Times Online.

- Weisman, Steven (March 17, 2006). "Rice and Australian Counterpart Differ About China". The New York Times.

- Australia and Japan cosy up. The Economist. March 16, 2007.

- Graeme Dobell (March 18, 2007). Japan, Australia declare strategic partnership. ABC News Online Australia.

- Walters, Patrick; Callick, Rowan (March 16, 2007). India's inclusion in security pact risks alienating China. The Australian.

- "Inside the first ever U.S.-Japan-India trilateral meeting". Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "The Australia–India–Japan trilateral: converging interests… and converging perceptions? - The Strategist". 17 March 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Thrall, A. Trevor (September 17, 2019). "Selling F-16s to Taiwan Is Bad Business". Defense One. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "China and South Korea: Examining the Resolution of the THAAD Impasse".

- Sackur, Stephen (12 April 2011). "Australia leases out mineral-rich land as China's hunger for resources grows". The Guardian. London.

- "Rice says China must not become a negative force". 2006-03-11.

- "Rice: US Has No Policy of Containment Against China - china.org.cn". www.china.org.cn. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Thakurta, Paranjoy Guha (March 15, 2006). "China could overtake US's India trade". Asia Times Online.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Brennan, David (July 9, 2019). "'Let's Bomb Everything': Philippines President Duterte Urges U.S. To Declare War on China". Newsweek. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "East Asia/Southeast Asia :: Korea, South — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

External links

- US told to make China its No 1 enemy

- Containing China: The US's real objective

- WikiLeaks: Hillary Clinton's question: how can we stand up to Beijing?

- China and USA in New Cold War over Africa’s oil riches

- America's Unsinkable Fleet

- Obama and China: 21st Century containment in three moves

- Offshore Control: A Proposed Strategy for an Unlikely Conflict

- Recalibrating American Grand Strategy: Softening US Policies Toward Iran In Order to Contain China

- The View from China

- The China Reckoning: How Beijing Defied American Expectations by Kurt M. Campbell and Ely Ratner