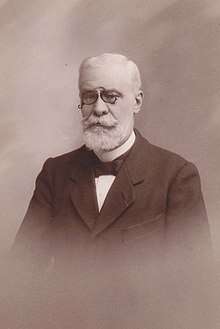

Charles Janet

Charles Janet (French: [ʒanɛ]; 15 June 1849 – 7 February 1932) was a French engineer, company director, inventor and biologist. He is also known for his innovative left-step presentation of the periodic table of chemical elements.[1]

Life and work

Janet graduated from the École des Mines and worked for some years in munitions. He then married the daughter of the owner of a manufacturing company and worked for it for the rest of his life, finding time for research in various branches of science. His collection of 40,000 fossils and other specimens was unfortunately dispersed after his death.[2] His studies of the morphology of the head of ants, wasps and bees, and his micrographs were of remarkable quality.[3] He also worked on plant biology and finally wrote a series of papers on evolution. He was a prolific inventor and designed much of his own equipment, including the formicarium, in which an ant colony is made visible by being formed between two panes of glass.[4] In 1927 he turned his attention to the periodic table and wrote a series of six articles in French, which were privately printed and never widely circulated. His only article in English was poorly edited and gave a confused idea of his thinking.[5]

Chemical ideas

Janet started from the fact that the series of chemical elements is a continuous sequence, which he represented as a helix traced on the surfaces of four nested cylinders. By various geometrical transformations he derived several striking designs, one of which is his "left-step Periodic Table", in which hydrogen and helium are placed above lithium and beryllium. It was only later that he realized that his arrangement agreed perfectly with quantum theory and the electronic structure of the atom. He placed the actinides under the lanthanides twenty years before Glenn Seaborg, and he continued the series to element 120.

Janet's table differs from the standard table in placing the s-block elements on the right, so that the subshells of the periodic table are arranged in the order (n-3)s, (n-2)p, (n-1)d, nf from left to right. There is then no need to interrupt the sequence or move the f block into a 'footnote'. He believed that no elements heavier than number 120 would be found, so he did not envisage a g block. In terms of atomic quantum numbers, each row corresponds to one value of the sum (n + ℓ) where n is the principal quantum number and ℓ the azimuthal quantum number. The table therefore corresponds to the Madelung rule, which states that atomic subshells are filled in order of increasing values of (n + ℓ).

| f1 | f2 | f3 | f4 | f5 | f6 | f7 | f8 | f9 | f10 | f11 | f12 | f13 | f14 | d1 | d2 | d3 | d4 | d5 | d6 | d7 | d8 | d9 | d10 | p1 | p2 | p3 | p4 | p5 | p6 | s1 | s2 | |

| 1s | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2s | Li | Be | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2p 3s | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | Na | Mg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3p 4s | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | K | Ca | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3d 4p 5s | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | Rb | Sr | ||||||||||||||

| 4d 5p 6s | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | Cs | Ba | ||||||||||||||

| 4f 5d 6p 7s | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | Fr | Ra |

| 5f 6d 7p 8s | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og | 119 | 120 |

| f-block | d-block | p-block | s-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Janet also envisaged an element zero whose 'atom' would consist of two neutrons,[6] and he speculated that this would be the link to a mirror-image table of elements with negative atomic numbers – in effect anti-matter. He also conceived of heavy hydrogen (deuterium). He died just before the discovery of the neutron, the positron and heavy hydrogen.[1] His work was championed most notably by Edward G. Mazurs.[7]

References and notes

- Stewart, Philip (April 2010). "Charles Janet:unrecognized genius of the Periodic System". Foundations of Chemistry. 12: 5–15. doi:10.1007/s10698-008-9062-5.

- Casson, Loic (2008). "Notice biographique sur la vie et l'oeuvre de Charles Janet". Bulletin de la Societe Academique de l'Oise.

- Johan Bollin and Edward O. Wilson, 'Social insect histology from the 19th century: the magnificent pioneer sections of Charles Janet, (2008) Arthropod Structure and Development 37, 163–167

- Janet, Charles (1893). "Appareil pour l'élevage et l'observation des fourmis". Annales de la Société Entomologique de France. 62: 467.

- Janet, Charles (June 1929). "The helicoidal classification of the elements". Chemical News.

- At this time the neutron was an undiscovered particle which had been proposed by Ernest Rutherford and others. See Discovery of the neutron#Rutherford atom

- Mazurs, Edward G. (1974). Graphic Representations of the Periodic System during One Hundred Years. University of Alabama Press. p. 251. ISBN 0-8173-3200-6.

External links

- (in French) Biographie synthétique de Charles Janet

- Eric Scerri's website http://www.ericscerri.com