Carlton House Terrace

Carlton House Terrace is a street in the St James's district of the City of Westminster in London. Its principal architectural feature is a pair of terraces of white stucco-faced houses on the south side of the street overlooking St. James's Park. These terraces were built on Crown land between 1827 and 1832 to overall designs by John Nash, but with detailed input by other architects including Decimus Burton, who exclusively designed No. 3 and No.4.

History

Background

The land on which Carlton House Terrace was built had once been part of the grounds of St James's Palace, known as "the Royal Garden" and "the Wilderness". The latter was at one time in the possession of Prince Rupert of the Rhine (cousin of Charles II), and was later called Upper Spring Garden.[1]

From 1700 the land was held by Henry Boyle, who spent £2,835 on improving the existing house in the Royal Garden.[2] Queen Anne issued letters patent granting Boyle a lease for a term of 31 years from 2 November 1709 at £35 per annum.[2] Boyle was created Baron Carleton in 1714, and the property has been called after him since then, although at some point the "e" was dropped.[n 1]

On Carleton's death the lease passed to his nephew, the architect and aesthete Lord Burlington, and in January 1731 George II issued letters patent granting Burlington a reversionary lease for a further term of 40 years at an annual rent of £35.[1] By an indenture dated 23 February 1732 the lease was assigned to Frederick, Prince of Wales, eldest son of George II, who predeceased his father, dying in 1751; his widow, Augusta, continued living in the house, making alterations and purchasing an adjoining property to enlarge the site. She died in 1772 and the house devolved to her son, George III.[2]

The property was granted by George III to his eldest son, George, Prince of Wales (later Prince Regent) on the latter's coming of age in 1783. The Prince spent enormous sums on improving and enlarging the property, running up huge debts. He was at loggerheads with his father, and the house became a rival Court, and was the scene of a brilliant social life.[2]

When the Prince became King George IV in 1820 he moved to Buckingham Palace. Instructions were given in 1826 to the Commissioners of Woods and Forests that "Carlton Palace" should be given up to the public, be demolished and the site and gardens laid out as building ground for "dwelling houses of the First Class".[3] By 1829 the Commissioners reported that the site was completely cleared and that part of it had already been let on building leases.[4] Materials from the demolition were sold by public auction, with some fixtures transferred to Windsor Castle and to "The King's House, Pimlico". Columns of the portico were re-used in the design for the new National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, interior Ionic columns were moved to the conservatories of Buckingham Palace, and some of the armorial stained glass was incorporated in windows of Windsor Castle.[4]

Construction

After Carlton House was demolished the development of its former site was originally intended to be part of a scheme for improving St James's Park. For this John Nash proposed three terraces of houses along the north of the Park, balanced by three along the south side, overlooking Birdcage Walk. None of the three southern terraces and only two of the three northern ones were built, the latter being the west (No.1–9) and east (No. 10–18) sections of Carlton House Terrace.[n 2] These two blocks were designed by Nash and Decimus Burton, with James Pennethorne in charge of the construction. Decimus Burton exclusively, without Nash, designed No. 3 and No. 4. Carlton House Terrace.[6] These elegant townhouses took the place of Carlton House, and the freehold still belongs to the Crown Estate. Nash planned to make contiguous the two blocks with a large domed fountain between them (re-using the old columns of the Carlton House portico), but the idea was vetoed by the King;[7] the present-day Duke of York's Steps took the place of the fountain. In 1834 the Duke of York's Column was erected at the top of the steps. It consists of a granite column designed by Benjamin Wyatt topped with a bronze statue by Richard Westmacott of Frederick, Duke of York.[8]

The terraces, which are four storeys in height above a basement, were designed in a classical style, stucco clad, with a Corinthian columned façade overlooking St James's Park, surmounted by an elaborate frieze and pediment. At the south side, facing the park, the lower frontage has a series of squat Doric columns, supporting a substantial podium terrace at a level between the street entrances to the north and the ground floor level of the modern Mall.[7] The houses are unusual as they are expensive London terraces which have no mews to the rear. The reason for this was that Nash wanted the houses to make the best possible use of the view of the park, and also to present an attractive façade to the park. The service accommodation was placed underneath the podium and in two storeys of basements (rather than the usual one storey).[9]

According to the architectural historian Sir John Summerson Nash's designs were inspired by Ange-Jacques Gabriel's buildings in the Place de la Concorde, Paris. Summerson's praise of the buildings is muted:

The central pediments are a somewhat too contrived means of preventing an apparent sag in a very long façade and the attics on the end pavilions may be over-emphatic. Subtlety of modelling there is none. In fact, Carlton House Terrace is thoroughly typical of the extraordinary old man who designed it, but whose only contribution to the work was probably the provision of a few small sketches, done either in the glorious painted gallery of his Regent Street mansion or the flower-scented luxury of his castle in the Isle of Wight.[7]

The authors of the Survey of London take a more favourable view:

The houses … form a double group each side of the Duke of York's Column. Designed as an architectural entity, facing the Park, they represent with their range of detached Corinthian columns, a pleasing example of comprehensive street architecture; an effect greatly enhanced by the freshness of their façades … The end house to each block is carried up above the roof of the main façade, thereby effecting a successful pavilion treatment. The return fronts of the houses facing the steps are also effectively treated in a complementary manner.[9]

Although Nash delegated the supervision of building to Pennethorne, he kept the letting of the sites firmly in his own hands. Ground rents, payable to the Crown, were set at the high rate of 4 guineas per foot frontage. Nash himself took leases of five sites – nos 11–15 intending to let them on the open market at a substantial profit. In the event he could not cover his total costs and made a small loss on the transactions.[7]

Later history

In the 20th century the Terrace came under threat of partial or complete demolition and redevelopment, as were country houses at that time. By the 1930s there was little demand for large central London houses, and the Commissioners of Crown Lands were having difficulty in letting the properties. Two properties were let to clubs: no 1 to the Savage Club and no 16 to Crockford's gambling club, but residential tenants became hard to find.[7] Proposals for redevelopment were put forward by the architect Sir Reginald Blomfield, who had earlier been one of those responsible for replacing Nash's Regent Street buildings with larger structures in the Edwardian neo-classical style. Blomfield proposed rebuilding "in a manner suitable for hotels, large company offices, flats and similar purposes".[10] The suggested new buildings were to be two storeys higher than Nash's houses, and there was an outcry that persuaded the Commissioners not to proceed with the scheme.[11]

The Terrace was severely damaged by German bombing during the Second World War. In the 1950s the British government considered acquiring the Terrace as the site for a new Foreign Office headquarters. The Nash façades were to be preserved, but it was widely felt that the height of the redevelopment behind them would be unacceptable.[12]

Occupants

The Terrace has had many famous residents, including:

- Lord Cardigan (leader of the Charge of the Light Brigade): occupied number 17 from 1832–36.[13]

- Lord Palmerston (Prime Minister): at Number 5 from 1840–46.

- Earl Grey (Prime Minister): at Number 13 from 1851–57 and again from 1859–80.

- William Ewart Gladstone (Prime Minister): at Number 4 in 1856 and Number 11 from 1857–75.

- Lord Curzon (Foreign Secretary and Viceroy of India): at Number 1 from 1905–25.

- Lord Revelstoke (Baring family and Barings bank principal partner): at Number 3 from 1904–29.

- William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor (American-born businessman): at Number 18 during at least 1906–1909.[14]

- Joachim von Ribbentrop (German Ambassador): at Numbers 8 and 9 from 1936–38.[15] (The Prussian Legates, and later their successors the German Ambassadors, inhabited no 9 from 1849 until the Second World War, eventually taking no 8 also.)

- Ashraf Marwan (Egyptian billionaire arms dealer and former spy): died after somehow falling from his flat in the terrace. [16]

- MI6's Section Y was housed in Number 3, Carlton Gardens (see below) after the Second World War for an undisclosed time. This department, headed by Col. Tom Grimson, analysed wiretap information and compared it with information from other sources. The British traitor George Blake was his deputy, and he was brought here for interrogation after his capture in 1961.[17]

Most of the houses are now occupied by businesses, institutes and learned societies.

- Number 1 was the headquarters of the Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining from 1972 to 2015[18] and in April 2020 was owned by Salah Hamdan Albluewi through SAB Ventures.[19]

- Number 2 is the UK branch of Carmignac Gestion[20]

- Numbers 3-4 house the Royal Academy of Engineering.

- Number 5 is the location of the Turf Club.

- Numbers 6–9 are now the home of the Royal Society (formerly 9, the Prussia House, was the German Embassy until 1945; it is now in Belgrave Square).

- Numbers 10–11 house the British Academy.

- Number 12 is the Institute of Contemporary Arts, which also occupies much of the basement of the East Terrace.

- Numbers 13–16 are privately owned by the four Hinduja brothers, industrialists from India.[21]

- Number 17 is home to the Federation of British Artists and the Mall Galleries.

- Number 18 is a private residence.

- Number 20,a purpose built 1970's office building over a four level basement car park on the north side of the thoroughfare, is the global headquarters of mining company Anglo American plc.

- Number 24 is a 1970's purpose built block of 15 flats adjoining Number 20.

The Crown Estate had its headquarters for many years in four houses in the Terrace (Numbers 13–16). However, the organisation moved in 2006 to another property that it owns in New Burlington Place, an alleyway off Regent Street. In 2006, the Hinduja family purchased the vacated property for £58 million.[22]

Carlton Gardens

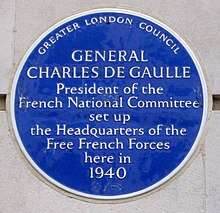

At the west end of the Carlton House Terrace is a cul-de-sac called Carlton Gardens, which was developed at around the same time. It contained seven large houses. Robert Loyd-Lindsay, founder of the British Red Cross inherited Number 2 from his father-in-law Samuel Jones-Loyd, 1st Baron Overstone in 1883, and it remained his London residence until his death in 1901. His widow Lady Wantage later briefly leased Number 2 to Lord Kitchener. Number 4 was home to Lord Palmerston for a time and later served as Charles de Gaulle's government in exile, Free France.

All the houses except numbers 1, 2 and 3 have been replaced by office blocks. Number 1 is an official ministerial residence normally used by the Foreign Secretary.[23] Number 2 is used by the Privy Council Office.[24] Number 3 has been owned by billionaire hedge fund manager Ken Griffin since January 2019.[25]

Notes

- The location is shown as "Charlton House" in Roque's 1746 map of London.

- Nash's plans included the demolition of Marlborough House to the west, replacing it with the third terrace; this idea was reflected in some contemporary maps, including Christopher and John Greenwood's large scale London map of 1830,[5] but this proposal was not implemented.

References

- Pithers (2005), p. 1.

- Gater, G. H.; Hiorns, F. R., eds. (1940). "Chapter 8: Carlton House". Survey of London: Volume 20, St Martin-in-The-Fields, Pt III: Trafalgar Square & Neighbourhood. London: London County Council. pp. 69–76. Retrieved 2 September 2013 – via British History Online.

- Regent Street, Carlton Place Act 1826 (Act 7 Geo IV cap 77)

- Pithers (2005), p. 2.

- "Greenwood Map of London 1830". MOTCO – Image Database. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 135–157. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Pithers (2005), p. 3.

- Bullus, Asprey & Gilbert (2008), p. 240.

- Gater, G. H.; Hiorns, F. R., eds. (1940). "Chapter 9: Carlton House Terrace and Carlton Gardens". Survey of London: Volume 20, St Martin-in-The-Fields, Pt III: Trafalgar Square & Neighbourhood. London: London County Council. pp. 77–87. Retrieved 2 September 2013 – via British History Online.

- "Carlton House Terrace". The Times. 16 December 1932. p. 10.

- "The Crown Landlord". The Times. 19 December 1932. p. 13.

- "No F.O. at Carlton House Terrace". The Times. 2 December 1960. p. 14.

- "Carlton House Terrace and Carlton Gardens". Survey of London, Volume 20. British History Online. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "Kelly's Handbook to the Titled, Landed and Official Classes". London. 25 January 1888. Retrieved 25 January 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- "History of 6–9 Carlton House Terrace". Royal Society. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015.

- Syal, Rajeev (5 October 2008). "Yard probes billionaire spy's death". The Observer. London. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- Dorril, Stephen (2000). MI6: Fifty Years of Special Operations. London: Fourth Estate Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85702-093-9.

- "History of the Institute". IOM3.

- https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2020/1313.html

- "CARMIGNAC GESTION LUXEMBOURG S.A., UK BRANCH". Companies House Registry. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Karmali, Naazneen (8 October 2013). "Carlton House Terrace: The Hindujas' New $500 Million Real Estate Masterpiece". Forbes.

- Nelson, Dean; Chittenden, Maurice (27 August 2006). "Hindujas to build 'palace' on the Mall". The Sunday Times.

- "Written Answers to Questions: Foreign and Commonwealth Office: 1 Carlton Gardens". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 6 May 2009. col. 165W.

- "Contacting the Privy Council Office". privy-council.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008.

- Morrison, Sean (21 January 2019). "Hedge fund tycoon buys £95m mansion overlooking Buckingham Palace in most expensive UK home sale since 2011". United Kingdom: The Evening Standard (London). ESI Media. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- Bibliography

- Bullus, Claire; Asprey, Ronald; Gilbert, Dennis (2008). The Statues of London. London: Perseus. ISBN 1858944724.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pithers, Margaret (2005). A Short History of 13–16 Carlton House Terrace. London: The Crown Estate.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carlton House Terrace. |

- "Carlton House Terrace". Royal Society. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010.

- "10-11 Carlton House Terrace".