Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure

The Ewok Adventure is a 1984 American television film based in the Star Wars universe, which takes place on the moon of Endor between the events of Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back and Episode VI – Return of the Jedi.[2][3] It features the Ewoks, who help two young human siblings as they try to locate their parents.

Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure

| |

|---|---|

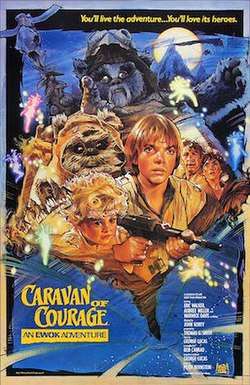

Promotional poster | |

| Also known as | The Ewok Adventure |

| Genre |

|

| Screenplay by | Bob Carrau |

| Story by | George Lucas |

| Directed by | John Korty |

| Starring |

|

| Narrated by | Burl Ives |

| Theme music composer | Peter Bernstein |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) | George Lucas |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Production location(s) | Marin County, California |

| Cinematography | John Korty |

| Editor(s) | John Nutt |

| Running time | 97 minutes[1] |

| Production company(s) |

|

| Distributor | |

| Release | |

| Original network | ABC |

| Picture format | Color |

| Audio format | Dolby |

| Original release |

|

| Chronology | |

| Followed by | Ewoks: The Battle for Endor |

The film was given a limited international theatrical run, for which it was retitled Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure. It was followed by a sequel, Ewoks: The Battle for Endor, in 1985.

Plot

On the forest moon of Endor, the Towani family starcruiser lies wrecked. The Towani family (Catarine, Jeremitt, Mace and Cindel) are stranded. When Catarine and Jeremitt vanish (having been captured by the Gorax), the children are found by the Ewok Deej. After Mace tries to kill them, the Ewoks subdue him and take both children to the Ewoks’ home. There, Cindel and Wicket become friends. Shortly thereafter, the Ewoks kill a boar wolf only to find a life-monitor from one of the Towani parents with the creature.

They seek out the Ewok Logray who informs them that the parents have been taken by the monstrous Gorax, which resides in a deserted, dangerous area. A caravan of Ewoks is formed to help the children find their parents. They meet up with a wistie named Izrina and a boisterous Ewok named Chukha-Trok before finally reaching the lair of the Gorax. They engage the Gorax in battle, freeing Jeremitt and Catarine, but Chukha-Trok is killed. The Gorax is thought destroyed when it is knocked into a chasm, but it takes a final blow from Mace (using Chukha-Trok's axe) to kill the creature, which tries to climb back up after them. Thus reunited, the Towanis decide to stay with the Ewoks until they can repair the starcruiser, and Izrina leaves to go back to her family.

Cast

- Warwick Davis as Wicket W. Warrick

- Aubree Miller as Cindel Towani

- Eric Walker as Mace Towani

- Fionnula Flanagan as Catarine Towani

- Guy Boyd as Jeremitt Towani

- Daniel Frishman as Deej

- Debbie Lee Carrington as Weechee

- Tony Cox as Widdle

- Kevin Thompson as Chukha-Trok

- Margarita Fernández as Kaink

- Pam Grizz as Shodu

- Bobby Bell as Logray

- Burl Ives as Narrator (voice)

- Darryl Henriques as Wicket (voice) (as Daryl Henriquez)

- Sydney Walker as Deej (voice)

Production

Inception

George Lucas had allowed the Star Wars universe to be produced for television in 1978 with the Star Wars Holiday Special, which proved to be an embarrassment.[4] Lucas assumed greater control over a planned half-hour television project about Ewoks. He hired Thomas G. Smith to produce the film, after Smith had stepped down as the manager of Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) following his work on Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.[5][6] Lucas also hired Bob Carrau, the nanny of his children, to co-write the story with him.[5]

When shopping the film around, Smith discovered that none of the TV networks at the time were interested in airing a half-hour special, but ABC showed interest in a two-hour movie of the week; the project was expanded to fill the request.[6] The producers initially conceived of the project as a cross between "Hansel and Gretel" and Tarzan of the Apes.[7] John Korty, who had directed the Lucas-produced Twice Upon a Time, was selected as director.

Crew

Working from a story written by George Lucas and a screenplay by Bob Carrau, director John Korty transformed the scenic northern California redwood forests into the forest moon of Endor. Joe Johnston, an art director at ILM for years and one of the key concept artists of the classic Star Wars trilogy, acted as production designer and second-unit director.[6] Prior to the movie's release, Johnston also wrote and illustrated a book about Ewoks, The Adventures of Teebo: A Tale of Magic and Suspense.[8]

Visual effects

Both Ewok films were some of the last intensive stop-motion animation work ILM produced, as by the early 1980s, the technique was being replaced by go motion, an advanced form of animation with motorized puppets that move while the camera shutter is open.[9] However, go motion was too expensive for the budgets of the Ewok films, so stop motion was used to realize creatures such as the Gorax.[6]

The Ewok movies proved an opportunity for ILM to use a technique innovated for 2001: A Space Odyssey called latent image matte painting.[10][11] In this technique, during live-action photography, a section of the camera lens is blocked off and remains unexposed. The film is rewound, the blocked areas reversed, and a painting crafted to occupy the space is photographed.

Music

The musical score for Caravan of Courage was composed by Peter Bernstein. Selections from the score were released on LP by Varèse Sarabande in 1986.[12] The release was known simply as Ewoks and also contained cues from Bernstein's score to the sequel Ewoks: The Battle for Endor.

Documentaries and commentary

During the production of Caravan of Courage, the children in the cast had to balance their school work with acting in the film. During their time on the set, Lucasfilm decided that it might be an educational and rewarding experience for the older children, Eric Walker (Mace) and Warwick Davis (Wicket), to be given their own camera to use between takes. Calling themselves W&W Productions, Eric and Warwick shot a documentary of the making of the film, which was released to Eric's YouTube channel in 2014.[13]

When the film was released on DVD in 2004 it contained nothing but the film itself. Eric Walker and Warwick Davis stated in interviews that they would be happy to record a cast commentary for another future DVD release, if Lucasfilm someday allowed a more detailed release of the films.

Adaptations

In 1985, Random House released a children's book adaptation of The Ewok Adventure by Amy Ehrlich, titled The Ewoks and the Lost Children,[14] which includes stills from the film.

Role in greater Star Wars continuity

Several elements from the film have gone on to appear in other works of the Star Wars Expanded Universe, which was declared non-canon and rebranded as Legends in 2014.[15]

- Ewoks: The Battle for Endor (1985) is the second of the two made-for-TV Ewok films. It dealt with the orphanage of Cindel, after her family was killed by Sanyassan Marauders. The marauders also kidnap many of the Ewoks. After meeting and being taken in by Noa Briqualon, Cindel, along with the Ewoks, must team up to defeat the marauders and free the others from their grasp.

- Ewoks (1985–1987) was an ABC animated series featuring the Ewoks that ran for two seasons. Set a few years before the original Star Wars trilogy,[16] it incorporates some elements introduced in The Ewok Adventure, such as the appearance of Queen Izrina of the Wisties in a couple of episodes.[17]

- Star Tours (1987) – When Disney and Lucasfilm joined forces for the Star Tours ride, Lucasfilm suggested that certain characters be included in the safety guide video before the ride began. However, an Ewok costume from The Ewok Adventure (opposed to another Ewok costume from Return of the Jedi) and Teek were included in the instructional short.

- Tyrant's Test (1996) – In the Star Wars Legends continuity, Cindel Towani went on to appear in Tyrant's Test, the third book of Michael P. Kube-McDowell's Star Wars book series, The Black Fleet Crisis trilogy. In the novel, set over ten years after The Battle for Endor, Cindel is shown to have grown to become a reporter on Coruscant. During the Yevethan crisis, Cindel received the so-called Plat Mallar tapes from Admiral Drayson, and leaked the story of the only survivor of the Yevethan attack of Polneye. The report was meant to garner sympathy among the people of the New Republic and the Senate; it worked. The Expanded Universe claims Cindel decided to join the New Republic and go into journalism after witnessing the Battle of Endor.

- Star Wars Galaxies: An Empire Divided (2003) is an MMORPG. In the game, the player has the opportunity to encounter the Gorax species.

- In an interview with Collider in December 2017, Gwendoline Christie supported the fan theory stating her character Captain Phasma from the films Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) and Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017), set in Star Wars canon, as being an older version of Cindel Towani.[18]

Release

The Ewok Adventure was first shown on American television November 25, 1984. In its overseas theatrical release, it was rechristened Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure. The film was released on VHS and Laserdisc in 1990 through MGM under the original title.

The film was released on DVD as a double feature collection with its sequel, Ewoks: The Battle for Endor, on November 23, 2004. The release was a single double-sided disc, with one film on each side. For this release, the film bore the theatrical release title, Caravan of Courage.

In January 2019, Disney and Lucasfilm released the film on Amazon's Prime Video service. It is available to rent and buy in Standard Definition.[19]

The streaming service Disney+ has announced no plans to host the Ewok films, prompting Eric Walker to start a petition for Disney to add them. According to Walker, he will personally deliver the petition to Lucasfilm stating, "if we can get 500,000 signatures I will show up as Mace Towani in costume."[20]

Reception

Critical response

In his review for The New York Times, John J. O'Connor noted the film's story as being almost "aggressively simple" and that "Mr. Lucas and crew do not come up with anything terribly astonishing."[21] With Marin County serving as the backdrop, looking "like some never-never land east of the Sun and west of the Moon," O'Connor recognized most of the interactions as following well-established cinematic tropes, the notable ones being between Cindel "looking like one of those little blond angels used to top off Christmas trees" and Wicket, a performance by the-then 14-year-old Warwick Davis, whom O'Connor called "the cleverest of the lot."[21]

Pointing to the main characters and plot elements, one pair of writers concluded that both Caravan of Courage and its sequel Battle for Endor are fairy tales despite occurring in a science fiction setting. They point to magical phenomena in both films, which is a fantasy element. They argue that in a science fiction story, the hero wants to disrupt or challenge the hierarchy of a supposed "utopian" society; whereas in both Ewok films, society is not challenged or disputed. Additionally, they argue, that while the Star Wars saga also has fairy tale tropes, it adhered more towards science fiction.[7] Another author agreed that the films are fairy tales, whereas "Science explains all magic."[22]

Accolades

The Ewok Adventure was one of four films to be juried-awarded Emmys for Outstanding Special Visual Effects at the 37th Primetime Emmy Awards.[23] The film was additionally nominated for Outstanding Children's Program but lost in this category to an episode of American Playhouse.[24]

See also

References

- "Caravan of Courage – An Ewok Adventure". British Board of Film Classification.

- Chee, Leland (Tasty Taste) (June 14, 2006). "Star Wars: Message Boards: Books, Comics, & Television VIPs". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2007. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- Anderson, Kevin J. (1995). The Illustrated Star Wars Universe. New York: Bantam Books. pp. 115, 132–33. ISBN 0-553-09302-9.

- Warren, Robert Burke (December 15, 2014). "The Flaw in the Forces: The Star Wars Holiday Special". TheWeeklings.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- Jones, Brian Jay (2016). George Lucas: A Life. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. p. 338. ISBN 978-0316257442.

- Alter, Ethan. "'Star Wars': How the Ewoks Came to TV 31 Years Ago". Yahoo. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- Douglas Brode; Leah Deyneka (June 14, 2012). Myth, Media, and Culture in Star Wars: An Anthology. Scarecrow Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-0-8108-8513-4.

- Joe, Johnston (1984). The Adventures of Teebo: A Tale of Magic and Suspense. Random House. ISBN 9780394865683.

- "The 5 Most Grueling Star Wars Visual Effects". StarWars.com. September 3, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- "Matte Effects – Return of The Jedi". The American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- Sawicki, Mark. "Filming the Fantastic: A Guide to Visual Effects Cinematography". American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- Osborne, Jerry (2010). Movie/TV Soundtracks and Original Cast Recordings Price and Reference Guide. Port Townsend, Washington: Osborne Enterprises Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 0932117376.

- Walker, Eric. "Star Wars Ewok Adventures Making Of Teaser". Retrieved December 9, 2015 – via YouTube.

- Ehrlich, Amy (1985). The Ewoks and the Lost Children. Random House. ISBN 9780394871868.

- "The Legendary Star Wars Expanded Universe Turns a New Page". StarWars.com. April 25, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- Veekhoven, Tim (September 3, 2015). "From Wicket to the Duloks: Revisiting the Star Wars: Ewoks Animated Series". StarWars.com. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Worthington, Clint; Roffman, Michael; Brennan, Collin; Gerber, Mckenzie; Caffrey, Dan (May 22, 2018). "Ranking: Every Star Wars Movie and TV Show from Worst to Best". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- "Andy Serkis, Gwendoline Christie & Domhnall Gleeson Share Their Favorite Snoke and Phasma Theories". Collifer. December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07LFKG96J/ref=cm_sw_r_cp_ep_dp_M8hyCb3CCP0R9_nodl

- Walker, Eric (September 24, 2019). "Disney+ May Not Be The Home To All of Star Wars – All For SciFi". All For SciFi. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- O'Connor, John J. (November 23, 1984). "TV Weekend; 'The Ewok Adventure,' Sunday Movie on ABC". The New York Times (Vol. 134, No. 46, 237). NYTimes Co. p. C34. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- Charles, Eric (2012). "The Jedi Network: Star Wars' Portrayal and Inspirations on the Small Screen". In Brode, Douglas; Deyneka, Leah (eds.). Myth, Media, and Culture in Star Wars: An Anthology. Scarecrow Press. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-0-810-88513-4. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- Leverence, John. "Outstanding Special Visual Effects – 1985". 37th Primetime Emmy Awards, September 22, 1985. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Outstanding Children's Program – 1985". 37th Primetime Emmy Awards, September 22, 1985. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

External links

- Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure on Wookieepedia, a Star Wars wiki

- Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure on IMDb

- The Ewok Adventure at AllMovie

- Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure at Rotten Tomatoes

- "Caravan of Courage: Celebrating 30 Years of An Ewok Adventure". Mark Newbold. starwars.com. (Dated 2014)

- "Before 'Rogue One': 'Ewok Adventure' Star on George Lucas' First 'Star Wars' Spinoff". Aaron Couch. (Dated 2016)