Bucephalus

Bucephalus or Bucephalas (/bjuːˈsɛfələs/; Ancient Greek: Βουκεφάλας, from βοῦς bous, "ox" and κεφαλή kephalē, "head" meaning "ox-head") (c. 355 BC – June 326 BC) was the horse of Alexander the Great, and one of the most famous horses of antiquity.[1]

Ancient accounts[2] state that Bucephalus died after the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC, in what is now modern Punjab Province of Pakistan, and is buried in Jalalpur Sharif outside Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan. Another account states that Bucephalus is buried in Phalia, a town in Pakistan's Mandi Bahauddin District in Punjab Province, which is named after him (Alexandria Bucephalous).

Bucephalus was named after a branding mark depicting an ox's head on his haunch.[3]

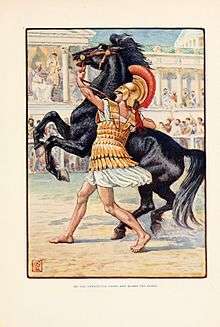

Taming of Bucephalus

A massive creature with a massive head, Bucephalus is described as having a black coat with a large white star on his brow. He is also supposed to have had a "wall eye" (blue eye), and his breeding was that of the "best Thessalian strain."

Plutarch says in 344 BC, at twelve or thirteen years of age, Alexander of Macedonia won the horse by making a wager with his father:[4] A horse dealer named Philonicus the Thessalian offered Bucephalus to King Philip II for the remarkably high sum of 13 talents. Because no one could tame the animal, Philip was not interested. However, Alexander was, and he offered to pay himself should he fail.

Alexander was given a chance and surprised all by subduing it. He spoke soothingly to the horse and turned it toward the sun so that it could no longer see its own shadow, which had been the cause of its distress. Dropping his fluttering cloak as well, Alexander successfully tamed the horse. Plutarch says that the incident so impressed Philip that he told the boy, "O my son, look thee out a kingdom equal to and worthy of thyself, for Macedonia is too little for thee."[4] Philip's speech strikes the only false note in the anecdote, according to AR Anderson,[5] who noted his words as the embryo of the legend fully developed in the History of Alexander the Great I.15, 17.

The Alexander Romance presents a mythic variant of Bucephalus's origin. In this tale, the colt, whose heroic attributes surpassed even those of Pegasus, is bred and presented to Philip on his own estates. The mythic attributes of the animal are further reinforced in the romance by the Delphic Oracle who tells Philip that the destined king of the world will be the one who rides Bucephalus, a horse with the mark of the ox's head on his haunch.

Alexander and Bucephalus

As one of his chargers, Bucephalus served Alexander in numerous battles.

The value which Alexander placed on Bucephalus emulated his hero and supposed ancestor Achilles, who claimed that his horses were "known to excel all others—for they are immortal. Poseidon gave them to my father Peleus, who in his turn gave them to me."[6]

Arrian states, with Onesicritus as his source, that Bucephalus died at the age of thirty. Other sources, however, give as the cause of death not old age or weariness, but fatal injuries at the Battle of the Hydaspes (June 326 BC), in which Alexander's army defeated King Porus. Alexander promptly founded a city, Bucephala, in honour of his horse. It lay on the west bank of the Hydaspes river (modern-day Jhelum in Pakistan).[7] The modern-day town of Jalalpur Sharif, outside Jhelum, is said to be where Bucephalus is buried.[8]

The legend of Bucephalus grew in association with that of Alexander, beginning with the fiction that they were born simultaneously: some of the later versions of the Alexander Romance also synchronized the hour of their death.[9] The pair forged a sort of cult in that, after them, it was all but expected of a conqueror that he have a favourite horse. Julius Caesar had one; so too did the eccentric Roman Emperor Caligula, who made a great fuss of his horse Incitatus, holding birthday parties for him, riding him while adorned with Alexander's breastplate, and planning to make him a consul.

In art and literature

Bucephalus is referenced in art and literature.

The ancient statue group The Horse Tamers in the Piazza del Quirinale in Rome is often misinterpreted as "Alexander and Bucephalus". An interpretation of their subject as Alexander and Bucephalus was proposed in 1558 by Onofrio Panvinio,[10] who suggested that Constantine had removed them from Alexandria, where they would have referred to the familiar legend of the city's founder. This became a popular alternative to their identification as the Dioscuri. The popular guides still referred to their creation by Phidias and Praxiteles competing for fame, long after even the modestly learned realized that the two sculptors preceded Alexander by a century.

Charles Le Brun (1619-1690) paintings of Alexandrine subjects, including Bucephalus, survive today in the Louvre. One in particular, The Passage of the Granicus, depicts the warhorse battling the difficulties of the steep muddy river banks, biting and kicking his foes.

In the 1959 French film The 400 Blows, there is a toy horse named Bucephalus.

The 1979 film The Black Stallion includes a story about Alexander taming Bucephalus that mirrors the events in the film.[11]

In the 1988 film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Baron Munchausen's horse is named Bucephalus.

The Crystal Bucephalus is an original 1994 Doctor Who novel written by Craig Hinton.

On the 1997 album Come to Daddy by Aphex Twin (Richard David James), he named one of his most impressive experimental tracks "Bucephalus Bouncing Ball" to incite listeners to think of great horses trotting into battle.

In the animated series Reign: The Conqueror, a sci-fi inspired rendition of the myth Bucephalus is a tall man-eating horse with a metallic jaw, prowling in Macedonia and killing everyone unfortunate enough to meet him. Alexander tames him, and like in the myth he becomes his faithful steed.

In the TV series Father Brown (premiered in 2013), the titular character's oft used bicycle is named Bucephalus.

The 2018 role-playing game Kingdom Come: Deliverance features a horse named Bucephalus that the player character can purchase.

In the 2006-2018+ Horus Heresy series of novels, Bucephalus is the name of the Emperor of Mankind's flagship.

Aired 2019-02-24, "Confection", the season 6 episode 3 of the television detective series Endeavour, features a fox hunt, where a murdered aristocrat named Creswell has an injured horse named Bucephalus.

Bucephalus also appears in the TV series Porus as the faithful horse of Alexander.

In the HBO series Watchmen, the now aged Adrian Veidt's prized horse is a grey horse named Bucephalus, which he rides about on his hidden estate. Veidt's alter ego in the original Watchmen graphic novel was Ozymandias (named after the Greek name for King Ramesses II). Veidt referenced Alexander the Great as someone he idolized as a boy.

See also

- Bucephalus (brand), an ox-head branding mark anciently used on horses

- Bucephalus (racehorse), an 18th-century Thoroughbred racehorse

- Bucephalus (trematode), a trematode flatworm genus

- HMS Bucephalus, an early 19th-century English naval vessel — see also Invasion of Java (1811).

- BTR-4 "Bucephalus", Ukrainian armored troop carrier

Notes

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bucephalus. |

- Aside from mythic Pegasus and the wooden Trojan Horse, or Incitatus, Caligula's favourite horse, proclaimed Roman consul.

- The primary (actually secondary) accounts are two: Plutarch's Life of Alexander, 6, and Arrian's Anabasis Alexandri V.19.

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1998). "Chapter One: The boyhood of Alexander". The Genius of Alexander the Great. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4744-5. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

Bucephalus, meaning 'Oxhead', so named from the brand-mark on his haunch, was a stallion some four years old.

- Arthur Hugh Clough (editor), John Dryden (translator), Plutarch's 'Lives', vol. II, Modern Library, 2001. ISBN 0-375-75677-9

- Anderson 1930:3 and 17ff.

- Homer, The Iliad, Book XXIII.

- Rolf Winkes, "Boukephalas", Miscellanea Mediterranea (Archaeologia Transatlantica XVIII) Providence 2000, pp. 101–107.

- Michael Wood, "In the footsteps of Alexander the Great".

- Andrew Runni Anderson, "Bucephalas and His Legend" The American Journal of Philology 51.1 (1930:1–21).

- Reipublicae Romanae Commentariorum (Venice, 1558), noted by Haskell and Penny, 1981.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cu0VOHIsdo4

External links