Brain in a vat

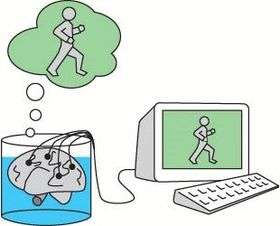

In philosophy, the brain in a vat (BIV) is a scenario used in a variety of thought experiments intended to draw out certain features of human conceptions of knowledge, reality, truth, mind, consciousness, and meaning. It is an updated version of René Descartes's evil demon thought experiment originated by Gilbert Harman.[1] Common to many science fiction stories, it outlines a scenario in which a mad scientist, machine, or other entity might remove a person's brain from the body, suspend it in a vat of life-sustaining liquid, and connect its neurons by wires to a supercomputer which would provide it with electrical impulses identical to those the brain normally receives.[2] According to such stories, the computer would then be simulating reality (including appropriate responses to the brain's own output) and the "disembodied" brain would continue to have perfectly normal conscious experiences, such as those of a person with an embodied brain, without these being related to objects or events in the real world.

Uses

The simplest use of brain-in-a-vat scenarios is as an argument for philosophical skepticism[3] and solipsism. A simple version of this runs as follows: Since the brain in a vat gives and receives exactly the same impulses as it would if it were in a skull, and since these are its only way of interacting with its environment, then it is not possible to tell, from the perspective of that brain, whether it is in a skull or a vat. Yet in the first case, most of the person's beliefs may be true (if they believe, say, that they are walking down the street, or eating ice-cream); in the latter case, their beliefs are false. Since the argument says one cannot know whether one is a brain in a vat, then one cannot know whether most of one's beliefs might be completely false. Since, in principle, it is impossible to rule out oneself being a brain in a vat, there cannot be good grounds for believing any of the things one believes; a skeptical argument would contend that one certainly cannot know them, raising issues with the definition of knowledge.

The brain-in-a-vat is a contemporary version of the argument given in Hindu Maya illusion, Plato's Allegory of the Cave, Zhuangzi's "Zhuangzi dreamed he was a butterfly", and the evil demon in René Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy.

Brain-in-a-vat scenarios—or closely related scenarios in which the protagonist is in a virtual reality simulation and unaware of this fact—have also been used for purposes other than skeptical arguments. For example, Vincent Conitzer uses such a scenario to illuminate further facts—facts that do not follow logically from the physical facts—about qualia (what it is like to have specific experiences), indexicality (what time it is now and who I am), and personal identity.[4] As an example, a person in the real world may observe a simulated world on a screen, from the perspective of one of the simulated agents in it. The person observing knows that besides the code responsible for the physics of the simulation, there must be additional code that determines in which colors the simulation is displayed on the screen, and which agent's perspective is displayed. (These questions are related to the inverted spectrum scenario and whether there are further facts about personal identity.) That is, the person can conclude that the facts about the physics of the simulation (which are completely determined by the code governing the physics) do not fully determine his experience on their own. But then, Conitzer argues, one could imagine a person who has become so engrossed in a VR simulation that he has forgotten that it is a simulation he is watching. That person could still reach the same conclusion, which means that our own conclusions about our own daily lives may be questionable.

Philosophical debates

While the disembodied brain (the brain in a vat) can be seen as a helpful thought experiment, there are several philosophical debates surrounding the plausibility of the thought experiment. If these debates conclude that the thought experiment is implausible, a possible consequence would be that we are no closer to knowledge, truth, consciousness, representation, etc. than we were prior to the experiment.

Argument from biology

One argument against the BIV thought experiment derives from the idea that the BIV is not – and cannot be – biologically similar to that of an embodied brain (that is, a brain found in a person). Since the BIV is dis embodied, it follows that it does not have similar biology to that of an embodied brain. That is, the BIV lacks the connections from the body to the brain, which renders the BIV neither neuroanatomically nor neurophysiologically similar to that of an embodied brain.[5][6] If this is the case, we cannot say that it is even possible for the BIV to have similar experiences to the embodied brain, since the brains are not equal. However, it could be counter-argued that the hypothetical machine could be made to also replicate those types of inputs.

Argument from externalism

A second argument deals directly with the stimuli coming into the brain. This is often referred to as the account from externalism or ultra-externalism.[7] In the BIV, the brain receives stimuli from a machine. In an embodied brain, however, the brain receives the stimuli from the sensors found in the body (via touching, tasting, smelling, etc.) which receive their input from the external environment. This argument oftentimes leads to the conclusion that there is a difference between what the BIV is representing and what the embodied brain is representing. This debate has been hashed out, but remains unresolved, by several philosophers including Uriah Kriegel,[8] Colin McGinn,[9] and Robert D. Rupert[10], and has ramifications for philosophy of mind discussions on (but not limited to) representation, consciousness, content, cognition, and embodied cognition.[11]

In fiction

- The Star Diaries

- Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Season 4

- "The Brain of Colonel Barham", a 1965 episode of the TV series The Outer Limits

- The Brain of Morbius

- Brainstorm

- Caprica

- The City of Lost Children

- Cold Lazarus

- The Colossus of New York[12]

- Dark Star

- Donovan's Brain

- Fallout

- Futurama

- Gangers in Doctor Who

- Inception

- Kavanozdaki Adam

- Lost, especially the season 3 episode ""Flashes Before Your Eyes", and the "flash-sideways" sequences in the sixth and last season

- The Man with Two Brains

- The Matrix film series

- "Out of Time", an episode of Red Dwarf

- Old World Blues, an expansion pack for Fallout: New Vegas

- Possible Worlds

- Psycho-Pass

- Repo Men

- RoboCop (most obvious with Cain in RoboCop 2)

- Saints Row IV

- "Ship in a Bottle", an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation

- Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri

- Soma

- Source Code

- "Spock's Brain", an episode of Star Trek: The Original Series

- Strange Days

- "The Inner Light", an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation

- The Thirteenth Floor

- Total Recall

- Transcendence

- "The Vacation Goo", an episode of American Dad!

- The Whisperer in Darkness

- Where am I?, written by Daniel Dennett

- William and Mary by Roald Dahl

- "White Christmas - Part II", an episode of Black Mirror

- World on a Wire

See also

References

- Harman, Gilbert 1973: Thought, Princeton/NJ, p.5.

- Putnam, Hilary. "Brains in a Vat" (PDF). Retrieved 21 April 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Klein, Peter (2 June 2015). "Skepticism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Conitzer, Vincent (2018). "A Puzzle about Further Facts". Erkenntnis. 84 (3): 727–739. arXiv:1802.01161. doi:10.1007/s10670-018-9979-6.

- Heylighen, Francis (2012). "A Brain in a Vat Cannot Break Out: Why the Singularity Must be Extended, Embedded, and Embodied". Journal of Consciousness Studies. 19 (1–2): 126–142.

- Thompson, Evan; Cosmelli, Diego (Spring 2011). "Brain in a Vat or Body in a World? Brainbound versus Enactive Views of Experience". Philosophical Topics. 39 (1): 163–180. doi:10.5840/philtopics201139119.

- Kirk, Robert (1997). "Consciousness, Information and External Relations". Communication and Cognition. 30 (3–4).

- Kriegel, Uriah (2014). Current Controversies in Philosophy of Mind. Routledge. pp. 180–95.

- McGinn, Colin (1988). "Consciousness and Content". Proceedings of the British Academy. 76: 219–39.

- Rupert, Robert (2014). The Sufficiency of Objective Representation. Current Controversies in Philosophy of Mind. Routledge. pp. 180–95.

- Shapiro, Lawrence (2014). When Is Cognition Embodied. Current Controversies in Philosophy of Mind. Routledge. pp. 73–90.

- "The Colossus of New York (1958)". monsterhuntermoviereviews.com. MonsterHunter. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

It turns out that Jeremy’s brain was sitting in a glass case of water hooked up to an EEG machine which led me to believe that they must have had some kind of clearance sale on set leftovers from Donovan’s Brain.

(with photo).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brain in a vat. |

- Philosophy

- Brueckner, Tony. "Skepticism and Content Externalism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Brain in a vat". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Simulation Hypothesis

- Inverse "brain in a vat"

- Putnam's discussion of the "brains in a vat" in chapter one of Reason, Truth, and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1981. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-52129776-9.

- 'Where Am I?' by Daniel Dennett

- "Brain in a Vat Brain Teaser" – Harper's Magazine (1996)

- Science