Boy

A boy is a young male human. The term is usually used for a child or an adolescent. When a male human reaches adulthood, he is described as a man.

| Part of a series on |

| Human growth and development |

|---|

|

| Stages |

| Biological milestones |

| Development and psychology |

|

Definition, etymology, and use

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a boy is "a male child from birth to adulthood".[1]

The word "boy" comes from Middle English boi, boye ("boy, servant"), related to other Germanic words for boy, namely East Frisian boi ("boy, young man") and West Frisian boai ("boy"). Although the exact etymology is obscure, the English and Frisian forms probably derive from an earlier Anglo-Frisian *bō-ja ("little brother"), a diminutive of the Germanic root *bō- ("brother, male relation"), from Proto-Indo-European *bhā-, *bhāt- ("father, brother"). The root is also found in Norwegian dialectal boa ("brother"), and, through a reduplicated variant *bō-bō-, in Old Norse bófi, Dutch boef "(criminal) knave, rogue", German Bube ("knave, rogue, boy"). Furthermore, the word may be related to Bōia, an Anglo-Saxon personal name.[2]

Specific uses

Race

Historically, in the United States and South Africa, "boy" was not only a "neutral" term for domestics but also a disparaging term towards men of color; the term implied a subservient status.[3][4][5][6] The use of the term "boy" to describe men of color has not always been used as an insult, however; for example, Thomas Branch, an early African-American Seventh-day Adventist missionary to Nyassaland (Malawi) referred to the native students as boys:

There is one way by which we judge many of our present boys to be quite different from some of those who were here long ago: those that are married have their wives here with them, and build their own houses, and all are busy making their gardens. I have told all the boys that if they wished to stay here and learn, those that had wives must bring them. This is having a good effect on them. They stay longer, and are more attentive to their work and their studies.[7]

Multiple politicians – including New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and former Kentucky Congressman Geoff Davis – have been criticized publicly for referring to a black man as "boy."[5][6]

During an event promoting the 2017 boxing bout between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Conor McGregor, the latter told the former to "dance for me, boy."[8] The remarks led several boxers – including Mayweather and Andre Ward – as well as multiple commentators to accuse McGregor of racism.[8][9][10][11]

Intersex and transgender issues

Some boys defy traditional gender expectations. Gender-expansive[lower-alpha 1] and transgender boys can face bullying and pressure to conform to traditional expectations.[12] Some intersex children and some transgender children who were assigned female at birth may self-identify as boys.[13]

Biology

Sex determination

Human sex is determined at fertilization when the genetic sex of the zygote has been initialized by a sperm cell containing either an X or Y chromosome. If this sperm cell contains an X chromosome, it will coincide with the X chromosome of the ovum and a girl will develop. A sperm cell carrying a Y chromosome results in an XY combination, and a boy will develop.[14]

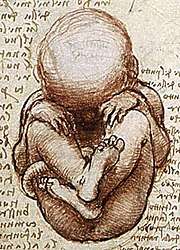

In utero development and genitalia

.jpg)

In male embryos at six to seven weeks' gestation, "the expression of a gene on the Y chromosome induces changes that result in the development of the testes". At approximately nine weeks' gestation, the production of testosterone by a male embryo results in the development of the male reproductive system.[15]

.jpg)

The male reproductive system includes both external and internal organs. The external organs include the penis, the scrotum, and the testicles (or testes). The penis is a cylindrical organ filled with spongy tissue. It is the organ used by boys to expel urine. The foreskin of some boys' penises is removed in a process known as circumcision. The scrotum is a loose sac of skin behind the penis which contains the testicles. Testicles are oval-shaped gonads. A boy generally possesses two testicles. Internal male reproductive organs include the vas deferens, the ejaculatory ducts, the urethra, the seminal vesicles, and the prostate gland.[16][17]

Physical maturation

Puberty is the process by which children's bodies mature into adult bodies that are capable of reproduction. On average, boys begin puberty at ages 11–12 and complete puberty at ages 16–17.[18][19]

In boys, puberty begins with the enlargement of the testicles and scrotum. The penis also increases in size, and a boy develops pubic hair. A boy's testicles also begin making sperm. The release of semen, which contains sperm and other fluids, is called ejaculation.[20] During puberty, a boy's erect penis becomes capable of ejaculating semen and impregnating a female.[16][17] A boy's first ejaculation is an important milestone in his development.[21] On average, a boy's first ejaculation occurs at age 13.[22] Ejaculation sometimes occurs during sleep; this phenomenon is known as a nocturnal emission.[20]

When a boy reaches puberty, testosterone triggers the development of secondary sex characteristics. A boy's muscles increase in size and mass, his voice deepens, his bones lengthen, and the shape of his face and body changes.[23] The increased secretion of testosterone from the testicles during puberty causes the male secondary sexual characteristics to be manifested.[24] Male secondary sex characteristics include:

- Growth of body hair, including underarm, abdominal, chest, and pubic hair.[25][23]

- Growth of facial hair.[23]

- Enlargement of larynx (Adam's apple) and deepening of voice.[23][26]

- Increased stature; adult males are taller than adult females, on average.[23]

- Heavier skull and bone structure.[23]

- Increased muscle mass and strength.[23]

- Broadening of shoulders and chest; shoulders wider than hips.[27]

- Increased secretions of oil and sweat glands.[26]

See also

References

- Notes

- The source[12] defines gender-expansive as: "Children who do not conform to their culture’s expectations for boys or girls. Being transgender is one way of being gender-expansive, but not all gender-expansive children are transgender."

- Footnotes

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/boy

- See:

- Etymology Online - entry for "boy"

- H. H. Malincrodt, Latijn-Nederlands woordenboek (Latin-Dutch dictionary)

- Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary

- Buck, Carl Darling (1988) [1949]. A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principal Indo-European Languages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07937-0.

- Corriher, Billy (2011-12-21). "Court finally says 'boy' comments are racist". Harvard Law and Policy Review. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Ifill, Sherrilyn A. (24 August 2010). "When 'Boy' Is Not a Racist Remark". The Root. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Martin, Roland S. (15 April 2008). "Understanding why you don't call a black man a boy". CNN.com. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- "Racist Or Not? Gov. Chris Christie Calls Black Man 'Boy' In Town Hall [VIDEO]". News One. 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Branch, Thomas H. (January 3, 1907). "British Central Africa" (PDF). Review and Herald. Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association. 84 (01): 18. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- Press Association (2017-07-15). "Floyd Mayweather accuses Conor McGregor of racism and uses homophobic slur". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Chiari, Mike (13 July 2017). "Andre Ward Doesn't Like Conor McGregor Calling Floyd Mayweather 'Boy'". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Callahan, Yesha (13 June 2017). "Yes, Conor McGregor Is a Racist". The Root. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Bell, Gabriel (14 July 2017). "Conor McGregor denies being a racist with racist statement". Salon. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Murchison, M.P.H., Gabe; et al. (September 2016). "Supporting & Caring for Transgender Children" (PDF). HRC.org.

- "Gender Identity: 5 Questions with Walter Bockting". Columbia University Irving Medical Center. 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- Fauci et al. 2008, pp. 2339-2346.

- Differences, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding the Biology of Sex and Gender; Wizemann, Theresa M.; Pardue, Mary-Lou (November 28, 2001). "Sex Begins in the Womb". National Academies Press (US) – via www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- "Male Reproductive System Information". Cleveland Clinic.

- "The Male Reproductive System". WebMD.

- Kail, RV; Cavanaugh JC (2010). Human Development: A Lifespan View (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-495-60037-4.

- D. C. Phillips (2014). Encyclopedia of Educational Theory and Philosophy. Sage Publications. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-4833-6475-9.

On average, the onset of puberty is about 18 months earlier for girls (usually starting around the age of 10 or 11 and lasting until they are 15 to 17) than for boys (who usually begin puberty at about the age of 11 to 12 and complete it by the age of 16 to 17, on average).

- "Puberty: Adolescent Male | Johns Hopkins Medicine". Hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- "Male puberty milestones". Health24. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- (Jorgensen & Keiding 1991).

- Bjorklund DF, Blasi CH (2011). Child and Adolescent Development: An Integrated Approach. Cengage Learning. pp. 152–153. ISBN 113316837X.

- Van de Graaff & Fox 1989, p. 933-4.

- Pack PE (2016). CliffsNotes AP Biology, 5th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 219. ISBN 0544784170.

- "Help is here!". hartnell.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009.

- "Secondary Characteristics". hu-berlin.de. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

Further reading

- Allen, Edward A. (1982). "Public School Elites in Early-Victorian England: The Boys at Harrow and Merchant Taylors' Schools from 1825 to 1850". Journal of British Studies. 21 (2): 87–117. doi:10.1086/385791.

- Baggerman, Arianne; Dekker, Rudolf (2009). Child of the Enlightenment: Revolutionary Europe Reflected in a Boyhood Diary.

- Clement, Priscilla Ferguson; Reinier, Jacqueline S., eds. (2001). Boyhood in America: an encyclopedia. 2 vol ABC-CLIO. description

- Giese, Rachel (2018). Boys: What it Means to Become a Man. Seal Press.

- Hunt, Peter (2004). International companion encyclopedia of children's literature. Routledge.

- Illick, Joseph E. (2005). American childhoods.

- Killian, Caitlin (2007). "Covered girls and savage boys: Representations of Muslim youth in France". Journal of Social and Ecological Boundaries. 3 (1): 69–90.

- Kugler, Adriana D.; Kumar, Santosh (2017). "Preference for boys, family size, and educational attainment in India". Demography. 54 (3): 835–859. doi:10.1007/s13524-017-0575-1.

- Liu, Fengshu (2006). "Boys as only‐children and girls as only‐children—parental gendered expectations of the only‐child in the nuclear Chinese family in present‐day China". Gender and Education. 18 (5): 491–505. doi:10.1080/09540250600881626.

- Macleod, David I. (1982). "Act Your Age: Boyhood, Adolescence and the Rise of the Boy Scouts of America". Journal of Social History. 16 (2): 3–20. doi:10.1353/jsh/16.2.3.

- Mintz, Steven (2004). Huck's raft: A history of American childhood. Harvard UP.

- Naka, Kansuke (2015). The Silver Spoon: Memoir of a Boyhood in Japan. Stone Bridge Press.

- Plafker, Ted (2002). "Sex selection in China sees 117 boys born for every 100 girls". The BMJ. 324 (7348): 1233. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7348.1233/a. PMC 1123206.

- Powell, Sacha; Smith, Kate, eds. (2017). An introduction to early childhood studies. Sage. from a variety of disciplines and international perspectives.

- Rose, Clare (2016). Making, selling and wearing boys' clothes in late-Victorian England. Routledge.

- Theriault, Daniel (2018). "A Socio-Historical Overview of Black Youth Development in the United States for Leisure Studies". International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure. 1 (2): 197–213. doi:10.1007/s41978-018-0013-y.

- Wainman, Ruth (2017). "'Engineering for Boys': Meccano and the Shaping of a Technical Vision of Boyhood in Twentieth-Century Britain". Cultural and Social History. 14 (3): 381–396.

- Wolff, Larry (1996). "The Boys Are Pickpockets, and the Girl Is a Prostitute": Gender and Juvenile Criminality in Early Victorian England from Oliver Twist to London Labour". New Literary History. 27 (2): 227–249. JSTOR 20057349.

External links

- Boyhood Studies, website and journal for the study of boys

- Historical Boys' Clothing