Borealopelta

Borealopelta (meaning "Northern shield") is a genus of nodosaurid ankylosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. It contains a single species, B. markmitchelli, named in 2017 by Caleb Brown and colleagues from a well-preserved specimen known as the Suncor nodosaur. Discovered at an oil sands mine north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, that is owned by the Suncor Energy company, the specimen is remarkable for being among the best preserved dinosaur fossils of its size ever found. It preserved not only the armor (osteoderms) in their life positions, but also remains of their keratin sheaths, overlying skin, and stomach contents from the animal's last meal. Melanosomes were also found that indicate the animal had a reddish skin tone.

| Borealopelta | |

|---|---|

| |

| The holotype specimen on display at the Royal Tyrell Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Family: | †Nodosauridae |

| Genus: | †Borealopelta Brown et al., 2017 |

| Species: | †B. markmitchelli |

| Binomial name | |

| †Borealopelta markmitchelli Brown et al., 2017 | |

Discovery and history

The Suncor Borealopelta was uncovered on March 21, 2011, at the Millennium Mine, an oil sands mine 30 kilometres (19 mi) north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, that is owned and operated by Suncor Energy.[1] The Wabiskaw Member sediments were being removed to allow mining of the underlying bitumen-rich sands of the McMurray Formation when an excavator struck the fossil. Noting the unusual nature of the exposed fragments, the operators alerted the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology. In accordance with Suncor's mining permit and Alberta fossil law, the specimen became the property of the Albertan government.[1]

On March 23, Royal Tyrrell Museum scientist Donald Henderson and senior technician Darren Tanke were brought to the mine to examine the specimen, which, based on photographs, they expected to be a plesiosaur or other marine reptile, as no land animals had ever been discovered in the oil sands previously.[1] Upon correct identification, which was made on site by Tanke, Henderson was astonished to learn that it was an ankylosaurian dinosaur and not a marine reptile. The animal had apparently been washed out to sea after death. [2]

After three days of mine safety training, museum staff and Suncor employees began working to recover all pieces of the fossil. Aside from the several pieces broken free, the bulk of the specimen was still embedded 8 metres (26 ft) up a cliff that was 12 metres (39 ft) high. The process took fourteen days in total.[1]

As the major piece of rock containing the fossil was being lifted out, it broke under its own weight into several pieces. Museum staff salvaged the specimen by wrapping and stabilizing the pieces in plaster, after which they were able to successfully transport them to the Royal Tyrell Museum. There, technician Mark Mitchell spent six years removing the adhering rock and preparing the fossil for study, which was sponsored by the National Geographic Society. The species B. markmitchelli was named for him in recognition of his skilled work.[1][3][4] The specimen was put on public exhibit on May 12, 2017, as part of the Royal Tyrrell Museum's "Grounds for Discovery" exhibition, along with other specimens discovered via industrial activity.[4]

Description

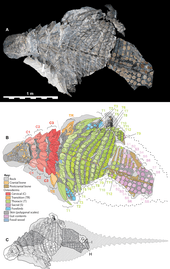

The Suncor Borealopelta is remarkable for its three-dimensional preservation of a large, articulated dinosaur complete with soft tissue. While many small dinosaurs have been preserved with traces of soft tissues and skin, these are usually flattened and compressed during fossilization. Similar-looking hadrosaurid "mummies" have a shriveled, desiccated appearance due to their partial mummification prior to fossilization. The Suncor specimen, however, appears to have sunk upside-down onto the sea floor shortly after its death, causing the top half of the body to be quickly buried with minimal distortion. The result is a specimen that preserves the animal almost as it would have looked in life, without flattening or shriveling.[5][3]

The Suncor specimen preserved numerous closely spaced rows of small armor plates, or osteoderms, lining the top and sides of its broad body. From the shoulders protruded a pair of long spines, shaped like the horns of a bull. Study of the pigments present in remnants of skin and scales suggest that it might have had a reddish-brown coloration in life, with a countershaded pattern that was used for camouflage.[5][3]

Classification

Borealopelta was classified by Brown et al. within the Nodosauridae. In the phylogenetic analysis conducted by the authors, Borealopelta nested within nodosaurids more derived than Nodosaurus. The completed cladogram was a strict consensus in 480 different trees, each with slightly different results. In both strict consensus and majority rules cladograms Borealopelta nested with Pawpawsaurus and Europelta in a group of Albian nodosaurs, with Hungarosaurus being the next closest taxon. The phylogeny below displays the results of the strict consensus, excluding taxa outside Nodosauridae.[5][6]

| Nodosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

The discovery that Borealopelta possessed camouflage coloration indicates that it was under threat of predation, despite its large size, and that the armor on its back was primarily used for defensive rather than display purposes.[5] Additionally, the spikes of Borealopelta had a dual function as defensive weapons and potential display structures useful in attracting mates and in species recognition.[7] Examination of the specimen's stomach contents indicate that ferns were a major part of the animal's diet. The fact that ferns made up the majority of Borealopelta's last meal suggested that it was a highly selective feeder. Roughly six percent of the stomach contents contained charcoal as well, leading to the conclusion that Borealopelta was feeding in an area that was experiencing regrowth after a recent wildfire. Brown and colleagues inferred that the ferns themselves had been halfway through their growing season when ingested, suggesting that the Borealopelta individual ingested them in early or mid-summer, dying only a few hours afterward.[8]

Paleoecology

The Suncor Borealopelta was preserved in the marine sandstones and shales of the Wabiskaw Member of the Clearwater Formation, which were laid down during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous period, about 110–112 million years ago.[5] At that time, the region was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, an inland sea that stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico,[3][9] and the Wabiskaw sediments were being deposited in an offshore marine environment.[5]

The Borealopelta must have been washed out to sea, perhaps during a flood. The bloated carcass floated, possibly for weeks, until it burst and sank.[3] It landed on the seabed on its back with enough force to deform the immediately underlying sediments. About 15 centimetres (6 in) of sediment settled over the carcass prior to the release of body fluids, as evidenced by fluid-escape structures preserved in the sediments, and the body cavity became filled with sand. A siderite concretion began to form around the carcass shortly after its arrival on the seabed, which prevented scavenging and preserved the body intact, with its scales and osteoderms in their original configuration.[5]

References

- Henderson, Donald (13 May 2013). "A one-in-a-billion dinosaur find". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Chandler, Graham (19 May 2014). "Dinosaurs in the mines". Alberta Oil Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- "This Is the Best Dinosaur Fossil of Its Kind Ever Found". 12 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- "World's best-preserved armoured dinosaur revealed in all its bumpy glory". CBC News. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Brown, C.M.; Henderson, D.M.; Vinther, J.; Fletcher, I.; Sistiaga, A.; Herrera, J.; Summons, R.E. (2017). "An Exceptionally Preserved Three-Dimensional Armored Dinosaur Reveals Insights into Coloration and Cretaceous Predator-Prey Dynamics". Current Biology. 27 (16): 2514–2521.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.071. PMID 28781051.

- Brown, C.M.; Henderson, D.M.; Vinther, J.; Fletcher, I.; Sistiaga, A.; Herrera, J.; Summons, R.E. (2017). "Supplemental Information: An Exceptionally Preserved Three-Dimensional Armored Dinosaur Reveals Insights into Coloration and Cretaceous Predator-Prey Dynamics" (PDF). Current Biology. 27 (16): 2514–2521.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.071. PMID 28781051.

- Brown, C. M. (2017). "An exceptionally preserved armored dinosaur reveals the morphology and allometry of osteoderms and their horny epidermal coverings". PeerJ. 5: e4066. doi:10.7717/peerj.4066. PMC 5712211. PMID 29201564.

- Brown, C. M.; Greenwood, D. E.; Kalyniuk, J. E.; Braman, D. R.; Henderson, D. M.; Greenwood, C. L.; Basinger, J. F. (2020). "Dietary palaeoecology of an Early Cretaceous armoured dinosaur (Ornithischia; Nodosauridae) based on floral analysis of stomach contents". Royal Society. 7 (6): 200305. doi:10.1098/rsos.200305. ISSN 2054-5703.

- Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists and Alberta Geological Survey (1994). "The Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, Chapter 19: Cretaceous Mannville Group of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin". Compiled by Mossop, G.D. and Shetsen, I. Archived from the original on 2013-08-14. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

External links

- "Adrift at sea in the Early Cretaceous – the Fort McMurray armoured dinosaur" (video) – Donald Henderson for Royal Tyrrell Museum Speaker Series, 2012