Boolean satisfiability problem

In logic and computer science, the Boolean satisfiability problem (sometimes called propositional satisfiability problem and abbreviated SATISFIABILITY, SAT or B-SAT) is the problem of determining if there exists an interpretation that satisfies a given Boolean formula. In other words, it asks whether the variables of a given Boolean formula can be consistently replaced by the values TRUE or FALSE in such a way that the formula evaluates to TRUE. If this is the case, the formula is called satisfiable. On the other hand, if no such assignment exists, the function expressed by the formula is FALSE for all possible variable assignments and the formula is unsatisfiable. For example, the formula "a AND NOT b" is satisfiable because one can find the values a = TRUE and b = FALSE, which make (a AND NOT b) = TRUE. In contrast, "a AND NOT a" is unsatisfiable.

SAT is the first problem that was proven to be NP-complete; see Cook–Levin theorem. This means that all problems in the complexity class NP, which includes a wide range of natural decision and optimization problems, are at most as difficult to solve as SAT. There is no known algorithm that efficiently solves each SAT problem, and it is generally believed that no such algorithm exists; yet this belief has not been proven mathematically, and resolving the question of whether SAT has a polynomial-time algorithm is equivalent to the P versus NP problem, which is a famous open problem in the theory of computing.

Nevertheless, as of 2007, heuristic SAT-algorithms are able to solve problem instances involving tens of thousands of variables and formulas consisting of millions of symbols,[1] which is sufficient for many practical SAT problems from, e.g., artificial intelligence, circuit design,[2] and automatic theorem proving.

Basic definitions and terminology

A propositional logic formula, also called Boolean expression, is built from variables, operators AND (conjunction, also denoted by ∧), OR (disjunction, ∨), NOT (negation, ¬), and parentheses. A formula is said to be satisfiable if it can be made TRUE by assigning appropriate logical values (i.e. TRUE, FALSE) to its variables. The Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) is, given a formula, to check whether it is satisfiable. This decision problem is of central importance in many areas of computer science, including theoretical computer science, complexity theory,[3][4] algorithmics, cryptography and artificial intelligence.[5]

There are several special cases of the Boolean satisfiability problem in which the formulas are required to have a particular structure. A literal is either a variable, called positive literal, or the negation of a variable, called negative literal. A clause is a disjunction of literals (or a single literal). A clause is called a Horn clause if it contains at most one positive literal. A formula is in conjunctive normal form (CNF) if it is a conjunction of clauses (or a single clause). For example, x1 is a positive literal, ¬x2 is a negative literal, x1 ∨ ¬x2 is a clause. The formula (x1 ∨ ¬x2) ∧ (¬x1 ∨ x2 ∨ x3) ∧ ¬x1 is in conjunctive normal form; its first and third clauses are Horn clauses, but its second clause is not. The formula is satisfiable, by choosing x1 = FALSE, x2 = FALSE, and x3 arbitrarily, since (FALSE ∨ ¬FALSE) ∧ (¬FALSE ∨ FALSE ∨ x3) ∧ ¬FALSE evaluates to (FALSE ∨ TRUE) ∧ (TRUE ∨ FALSE ∨ x3) ∧ TRUE, and in turn to TRUE ∧ TRUE ∧ TRUE (i.e. to TRUE). In contrast, the CNF formula a ∧ ¬a, consisting of two clauses of one literal, is unsatisfiable, since for a=TRUE or a=FALSE it evaluates to TRUE ∧ ¬TRUE (i.e., FALSE) or FALSE ∧ ¬FALSE (i.e., again FALSE), respectively.

For some versions of the SAT problem, it is useful to define the notion of a generalized conjunctive normal form formula, viz. as a conjunction of arbitrarily many generalized clauses, the latter being of the form R(l1,...,ln) for some boolean operator R and (ordinary) literals li. Different sets of allowed boolean operators lead to different problem versions. As an example, R(¬x,a,b) is a generalized clause, and R(¬x,a,b) ∧ R(b,y,c) ∧ R(c,d,¬z) is a generalized conjunctive normal form. This formula is used below, with R being the ternary operator that is TRUE just when exactly one of its arguments is.

Using the laws of Boolean algebra, every propositional logic formula can be transformed into an equivalent conjunctive normal form, which may, however, be exponentially longer. For example, transforming the formula (x1∧y1) ∨ (x2∧y2) ∨ ... ∨ (xn∧yn) into conjunctive normal form yields

- (x1 ∨ x2 ∨ … ∨ xn) ∧

- (y1 ∨ x2 ∨ … ∨ xn) ∧

- (x1 ∨ y2 ∨ … ∨ xn) ∧

- (y1 ∨ y2 ∨ … ∨ xn) ∧ ... ∧

- (x1 ∨ x2 ∨ … ∨ yn) ∧

- (y1 ∨ x2 ∨ … ∨ yn) ∧

- (x1 ∨ y2 ∨ … ∨ yn) ∧

- (y1 ∨ y2 ∨ … ∨ yn);

while the former is a disjunction of n conjunctions of 2 variables, the latter consists of 2n clauses of n variables.

Complexity and restricted versions

Unrestricted satisfiability (SAT)

SAT was the first known NP-complete problem, as proved by Stephen Cook at the University of Toronto in 1971[6] and independently by Leonid Levin at the National Academy of Sciences in 1973.[7] Until that time, the concept of an NP-complete problem did not even exist. The proof shows how every decision problem in the complexity class NP can be reduced to the SAT problem for CNF[note 1] formulas, sometimes called CNFSAT. A useful property of Cook's reduction is that it preserves the number of accepting answers. For example, deciding whether a given graph has a 3-coloring is another problem in NP; if a graph has 17 valid 3-colorings, the SAT formula produced by the Cook–Levin reduction will have 17 satisfying assignments.

NP-completeness only refers to the run-time of the worst case instances. Many of the instances that occur in practical applications can be solved much more quickly. See Algorithms for solving SAT below.

SAT is trivial if the formulas are restricted to those in disjunctive normal form, that is, they are disjunction of conjunctions of literals. Such a formula is indeed satisfiable if and only if at least one of its conjunctions is satisfiable, and a conjunction is satisfiable if and only if it does not contain both x and NOT x for some variable x. This can be checked in linear time. Furthermore, if they are restricted to being in full disjunctive normal form, in which every variable appears exactly once in every conjunction, they can be checked in constant time (each conjunction represents one satisfying assignment). But it can take exponential time and space to convert a general SAT problem to disjunctive normal form; for an example exchange "∧" and "∨" in the above exponential blow-up example for conjunctive normal forms.

3-satisfiability

Like the satisfiability problem for arbitrary formulas, determining the satisfiability of a formula in conjunctive normal form where each clause is limited to at most three literals is NP-complete also; this problem is called 3-SAT, 3CNFSAT, or 3-satisfiability. To reduce the unrestricted SAT problem to 3-SAT, transform each clause l1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ ln to a conjunction of n − 2 clauses

- (l1 ∨ l2 ∨ x2) ∧

- (¬x2 ∨ l3 ∨ x3) ∧

- (¬x3 ∨ l4 ∨ x4) ∧ ⋯ ∧

- (¬xn − 3 ∨ ln − 2 ∨ xn − 2) ∧

- (¬xn − 2 ∨ ln − 1 ∨ ln)

where x2, ⋯ , xn − 2 are fresh variables not occurring elsewhere. Although the two formulas are not logically equivalent, they are equisatisfiable. The formula resulting from transforming all clauses is at most 3 times as long as its original, i.e. the length growth is polynomial.[8]

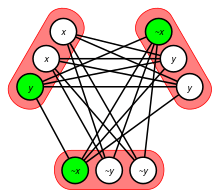

3-SAT is one of Karp's 21 NP-complete problems, and it is used as a starting point for proving that other problems are also NP-hard.[note 2] This is done by polynomial-time reduction from 3-SAT to the other problem. An example of a problem where this method has been used is the clique problem: given a CNF formula consisting of c clauses, the corresponding graph consists of a vertex for each literal, and an edge between each two non-contradicting[note 3] literals from different clauses, cf. picture. The graph has a c-clique if and only if the formula is satisfiable.[9]

There is a simple randomized algorithm due to Schöning (1999) that runs in time (4/3)n where n is the number of variables in the 3-SAT proposition, and succeeds with high probability to correctly decide 3-SAT.[10]

The exponential time hypothesis asserts that no algorithm can solve 3-SAT (or indeed k-SAT for any k > 2) in exp(o(n)) time (i.e., fundamentally faster than exponential in n).

Selman, Mitchell, and Levesque (1996) give empirical data on the difficulty of randomly generated 3-SAT formulas, depending on their size parameters. Difficulty is measured in number recursive calls made by a DPLL algorithm.[11]

3-satisfiability can be generalized to k-satisfiability (k-SAT, also k-CNF-SAT), when formulas in CNF are considered with each clause containing up to k literals. However, since for any k≥3, this problem can neither be easier than 3-SAT nor harder than SAT, and the latter two are NP-complete, so must be k-SAT.

Some authors restrict k-SAT to CNF formulas with exactly k literals. This doesn't lead to a different complexity class either, as each clause l1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ lj with j<k literals can be padded with fixed dummy variables to l1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ lj ∨ dj+1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ dk. After padding all clauses, 2k-1 extra clauses[note 4] have to be appended to ensure that only d1=⋯=dk=FALSE can lead to a satisfying assignment. Since k doesn't depend on the formula length, the extra clauses lead to a constant increase in length. For the same reason, it does not matter whether duplicate literals are allowed in clauses (like e.g. ¬x ∨ ¬y ∨ ¬y), or not.

Exactly-1 3-satisfiability

A variant of the 3-satisfiability problem is the one-in-three 3-SAT (also known variously as 1-in-3-SAT and exactly-1 3-SAT). Given a conjunctive normal form with three literals per clause, the problem is to determine whether there exists a truth assignment to the variables so that each clause has exactly one TRUE literal (and thus exactly two FALSE literals). In contrast, ordinary 3-SAT requires that every clause has at least one TRUE literal. Formally, a one-in-three 3-SAT problem is given as a generalized conjunctive normal form with all generalized clauses using a ternary operator R that is TRUE just if exactly one of its arguments is. When all literals of a one-in-three 3-SAT formula are positive, the satisfiability problem is called one-in-three positive 3-SAT.

One-in-three 3-SAT, together with its positive case, is listed as NP-complete problem "LO4" in the standard reference, Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness by Michael R. Garey and David S. Johnson. One-in-three 3-SAT was proved to be NP-complete by Thomas Jerome Schaefer as a special case of Schaefer's dichotomy theorem, which asserts that any problem generalizing Boolean satisfiability in a certain way is either in the class P or is NP-complete.[12]

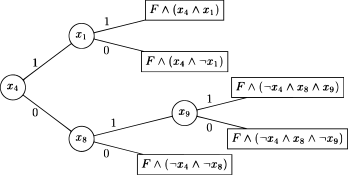

Schaefer gives a construction allowing an easy polynomial-time reduction from 3-SAT to one-in-three 3-SAT. Let "(x or y or z)" be a clause in a 3CNF formula. Add six fresh boolean variables a, b, c, d, e, and f, to be used to simulate this clause and no other. Then the formula R(x,a,d) ∧ R(y,b,d) ∧ R(a,b,e) ∧ R(c,d,f) ∧ R(z,c,FALSE) is satisfiable by some setting of the fresh variables if and only if at least one of x, y, or z is TRUE, see picture (left). Thus any 3-SAT instance with m clauses and n variables may be converted into an equisatisfiable one-in-three 3-SAT instance with 5m clauses and n+6m variables.[13] Another reduction involves only four fresh variables and three clauses: R(¬x,a,b) ∧ R(b,y,c) ∧ R(c,d,¬z), see picture (right).

Not-all-equal 3-satisfiability

Another variant is the not-all-equal 3-satisfiability problem (also called NAE3SAT). Given a conjunctive normal form with three literals per clause, the problem is to determine if an assignment to the variables exists such that in no clause all three literals have the same truth value. This problem is NP-complete, too, even if no negation symbols are admitted, by Schaefer's dichotomy theorem.[12]

2-satisfiability

SAT is easier if the number of literals in a clause is limited to at most 2, in which case the problem is called 2-SAT. This problem can be solved in polynomial time, and in fact is complete for the complexity class NL. If additionally all OR operations in literals are changed to XOR operations, the result is called exclusive-or 2-satisfiability, which is a problem complete for the complexity class SL = L.

Horn-satisfiability

The problem of deciding the satisfiability of a given conjunction of Horn clauses is called Horn-satisfiability, or HORN-SAT. It can be solved in polynomial time by a single step of the Unit propagation algorithm, which produces the single minimal model of the set of Horn clauses (w.r.t. the set of literals assigned to TRUE). Horn-satisfiability is P-complete. It can be seen as P's version of the Boolean satisfiability problem. Also, deciding the truth of quantified Horn formulas can be done in polynomial time. [14]

Horn clauses are of interest because they are able to express implication of one variable from a set of other variables. Indeed, one such clause ¬x1 ∨ ... ∨ ¬xn ∨ y can be rewritten as x1 ∧ ... ∧ xn → y, that is, if x1,...,xn are all TRUE, then y needs to be TRUE as well.

A generalization of the class of Horn formulae is that of renameable-Horn formulae, which is the set of formulae that can be placed in Horn form by replacing some variables with their respective negation. For example, (x1 ∨ ¬x2) ∧ (¬x1 ∨ x2 ∨ x3) ∧ ¬x1 is not a Horn formula, but can be renamed to the Horn formula (x1 ∨ ¬x2) ∧ (¬x1 ∨ x2 ∨ ¬y3) ∧ ¬x1 by introducing y3 as negation of x3. In contrast, no renaming of (x1 ∨ ¬x2 ∨ ¬x3) ∧ (¬x1 ∨ x2 ∨ x3) ∧ ¬x1 leads to a Horn formula. Checking the existence of such a replacement can be done in linear time; therefore, the satisfiability of such formulae is in P as it can be solved by first performing this replacement and then checking the satisfiability of the resulting Horn formula.

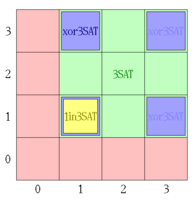

A formula with 2 clauses may be unsatisfied (red), 3-satisfied (green), xor-3-satisfied (blue), or/and 1-in-3-satisfied (yellow), depending on the TRUE-literal count in the 1st (hor) and 2nd (vert) clause. |

XOR-satisfiability

| Solving an XOR-SAT example by Gaussian elimination | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Another special case is the class of problems where each clause contains XOR (i.e. exclusive or) rather than (plain) OR operators.[note 5] This is in P, since an XOR-SAT formula can also be viewed as a system of linear equations mod 2, and can be solved in cubic time by Gaussian elimination;[15] see the box for an example. This recast is based on the kinship between Boolean algebras and Boolean rings, and the fact that arithmetic modulo two forms a finite field. Since a XOR b XOR c evaluates to TRUE if and only if exactly 1 or 3 members of {a,b,c} are TRUE, each solution of the 1-in-3-SAT problem for a given CNF formula is also a solution of the XOR-3-SAT problem, and in turn each solution of XOR-3-SAT is a solution of 3-SAT, cf. picture. As a consequence, for each CNF formula, it is possible to solve the XOR-3-SAT problem defined by the formula, and based on the result infer either that the 3-SAT problem is solvable or that the 1-in-3-SAT problem is unsolvable.

Provided that the complexity classes P and NP are not equal, neither 2-, nor Horn-, nor XOR-satisfiability is NP-complete, unlike SAT.

Schaefer's dichotomy theorem

The restrictions above (CNF, 2CNF, 3CNF, Horn, XOR-SAT) bound the considered formulae to be conjunctions of subformulae; each restriction states a specific form for all subformulae: for example, only binary clauses can be subformulae in 2CNF.

Schaefer's dichotomy theorem states that, for any restriction to Boolean operators that can be used to form these subformulae, the corresponding satisfiability problem is in P or NP-complete. The membership in P of the satisfiability of 2CNF, Horn, and XOR-SAT formulae are special cases of this theorem.[12]

Extensions of SAT

An extension that has gained significant popularity since 2003 is satisfiability modulo theories (SMT) that can enrich CNF formulas with linear constraints, arrays, all-different constraints, uninterpreted functions,[16] etc. Such extensions typically remain NP-complete, but very efficient solvers are now available that can handle many such kinds of constraints.

The satisfiability problem becomes more difficult if both "for all" (∀) and "there exists" (∃) quantifiers are allowed to bind the Boolean variables. An example of such an expression would be ∀x ∀y ∃z (x ∨ y ∨ z) ∧ (¬x ∨ ¬y ∨ ¬z); it is valid, since for all values of x and y, an appropriate value of z can be found, viz. z=TRUE if both x and y are FALSE, and z=FALSE else. SAT itself (tacitly) uses only ∃ quantifiers. If only ∀ quantifiers are allowed instead, the so-called tautology problem is obtained, which is co-NP-complete. If both quantifiers are allowed, the problem is called the quantified Boolean formula problem (QBF), which can be shown to be PSPACE-complete. It is widely believed that PSPACE-complete problems are strictly harder than any problem in NP, although this has not yet been proved. Using highly parallel P systems, QBF-SAT problems can be solved in linear time.[17]

Ordinary SAT asks if there is at least one variable assignment that makes the formula true. A variety of variants deal with the number of such assignments:

- MAJ-SAT asks if the majority of all assignments make the formula TRUE. It is known to be complete for PP, a probabilistic class.

- #SAT, the problem of counting how many variable assignments satisfy a formula, is a counting problem, not a decision problem, and is #P-complete.

- UNIQUE SAT[18] is the problem of determining whether a formula has exactly one assignment. It is complete for US,[19] the complexity class describing problems solvable by a non-deterministic polynomial time Turing machine that accepts when there is exactly one nondeterministic accepting path and rejects otherwise.

- UNAMBIGUOUS-SAT is the name given to the satisfiability problem when the input is restricted to formulas having at most one satisfying assignment. The problem is also called USAT.[20] A solving algorithm for UNAMBIGUOUS-SAT is allowed to exhibit any behavior, including endless looping, on a formula having several satisfying assignments. Although this problem seems easier, Valiant and Vazirani have shown[21] that if there is a practical (i.e. randomized polynomial-time) algorithm to solve it, then all problems in NP can be solved just as easily.

- MAX-SAT, the maximum satisfiability problem, is an FNP generalization of SAT. It asks for the maximum number of clauses which can be satisfied by any assignment. It has efficient approximation algorithms, but is NP-hard to solve exactly. Worse still, it is APX-complete, meaning there is no polynomial-time approximation scheme (PTAS) for this problem unless P=NP.

- WMSAT is the problem of finding an assignment of minimum weight that satisfy a monotone Boolean formula (i.e. a formula without any negation). Weights of propositional variables are given in the input of the problem. The weight of an assignment is the sum of weights of true variables. That problem is NP-complete (see Th. 1 of [22]).

Other generalizations include satisfiability for first- and second-order logic, constraint satisfaction problems, 0-1 integer programming.

Self-reducibility

The SAT problem is self-reducible, that is, each algorithm which correctly answers if an instance of SAT is solvable can be used to find a satisfying assignment. First, the question is asked on the given formula Φ. If the answer is "no", the formula is unsatisfiable. Otherwise, the question is asked on the partly instantiated formula Φ{x1=TRUE}, i.e. Φ with the first variable x1 replaced by TRUE, and simplified accordingly. If the answer is "yes", then x1=TRUE, otherwise x1=FALSE. Values of other variables can be found subsequently in the same way. In total, n+1 runs of the algorithm are required, where n is the number of distinct variables in Φ.

This property of self-reducibility is used in several theorems in complexity theory:

Algorithms for solving SAT

Since the SAT problem is NP-complete, only algorithms with exponential worst-case complexity are known for it. In spite of this, efficient and scalable algorithms for SAT were developed during the 2000s and have contributed to dramatic advances in our ability to automatically solve problem instances involving tens of thousands of variables and millions of constraints (i.e. clauses).[1] Examples of such problems in electronic design automation (EDA) include formal equivalence checking, model checking, formal verification of pipelined microprocessors,[16] automatic test pattern generation, routing of FPGAs,[23] planning, and scheduling problems, and so on. A SAT-solving engine is now considered to be an essential component in the EDA toolbox.

A DPLL SAT solver employs a systematic backtracking search procedure to explore the (exponentially sized) space of variable assignments looking for satisfying assignments. The basic search procedure was proposed in two seminal papers in the early 1960s (see references below) and is now commonly referred to as the Davis–Putnam–Logemann–Loveland algorithm ("DPLL" or "DLL").[24][25] Many modern approaches to practical SAT solving are derived from the DPLL algorithm and share the same structure. Often they only improve the efficiency of certain classes of SAT problems such as instances that appear in industrial applications or randomly generated instances.[26] Theoretically, exponential lower bounds have been proved for the DPLL family of algorithms.

Algorithms that are not part of the DPLL family include stochastic local search algorithms. One example is WalkSAT. Stochastic methods try to find a satisfying interpretation but cannot deduce that a SAT instance is unsatisfiable, as opposed to complete algorithms, such as DPLL.[26]

In contrast, randomized algorithms like the PPSZ algorithm by Paturi, Pudlak, Saks, and Zane set variables in a random order according to some heuristics, for example bounded-width resolution. If the heuristic can't find the correct setting, the variable is assigned randomly. The PPSZ algorithm has a runtime of for 3-SAT. This was the best-known runtime for this problem until a recent improvement by Hansen, Kaplan, Zamir and Zwick that has a runtime of for 3-SAT and currently the best known runtime for k-SAT, for all values of k. In the setting with many satisfying assignments the randomized algorithm by Schöning has a better bound.[10][27][28]

Modern SAT solvers (developed in the 2000s) come in two flavors: "conflict-driven" and "look-ahead". Both approaches descend from DPLL.[26] Conflict-driven solvers, such as conflict-driven clause learning (CDCL), augment the basic DPLL search algorithm with efficient conflict analysis, clause learning, non-chronological backtracking (a.k.a. backjumping), as well as "two-watched-literals" unit propagation, adaptive branching, and random restarts. These "extras" to the basic systematic search have been empirically shown to be essential for handling the large SAT instances that arise in electronic design automation (EDA).[29] Well known implementations include Chaff[30] and GRASP.[31] Look-ahead solvers have especially strengthened reductions (going beyond unit-clause propagation) and the heuristics, and they are generally stronger than conflict-driven solvers on hard instances (while conflict-driven solvers can be much better on large instances which actually have an easy instance inside).

Modern SAT solvers are also having significant impact on the fields of software verification, constraint solving in artificial intelligence, and operations research, among others. Powerful solvers are readily available as free and open source software. In particular, the conflict-driven MiniSAT, which was relatively successful at the 2005 SAT competition, only has about 600 lines of code. A modern Parallel SAT solver is ManySAT.[32] It can achieve super linear speed-ups on important classes of problems. An example for look-ahead solvers is march_dl, which won a prize at the 2007 SAT competition.

Certain types of large random satisfiable instances of SAT can be solved by survey propagation (SP). Particularly in hardware design and verification applications, satisfiability and other logical properties of a given propositional formula are sometimes decided based on a representation of the formula as a binary decision diagram (BDD).

Almost all SAT solvers include time-outs, so they will terminate in reasonable time even if they cannot find a solution. Different SAT solvers will find different instances easy or hard, and some excel at proving unsatisfiability, and others at finding solutions. All of these behaviors can be seen in the SAT solving contests.[33]

Parallel SAT-Solving

Parallel SAT solvers come in three categories: Portfolio, Divide-and-conquer and parallel local search algorithms. With parallel portfolios, multiple different SAT solvers run concurrently. Each of them solves a copy of the SAT instance, whereas divide-and-conquer algorithms divide the problem between the processors. Different approaches exist to parallelize local search algorithms.

The International SAT Solver Competition has a parallel track reflecting recent advances in parallel SAT solving. In 2016,[34] 2017[35] and 2018,[36] the benchmarks were run on a shared-memory system with 24 processing cores, therefore solvers intended for distributed memory or manycore processors might have fallen short.

Portfolios

In general there is no SAT solver that performs better than all other solvers on all SAT problems. An algorithm might perform well for problem instances others struggle with, but will do worse with other instances. Furthermore, given a SAT instance, there is no reliable way to predict which algorithm will solve this instance particularly fast. These limitations motivate the parallel portfolio approach. A portfolio is a set of different algorithms or different configurations of the same algorithm. All solvers in a parallel portfolio run on different processors to solve of the same problem. If one solver terminates, the portfolio solver reports the problem to be satisfiable or unsatisfiable according to this one solver. All other solvers are terminated. Diversifying portfolios by including a variety of solvers, each performing well on a different set of problems, increases the robustness of the solver.[37]

Many solvers internally use a random number generator. Diversifying their seeds is a simple way to diversify a portfolio. Other diversification strategies involve enabling, disabling or diversifying certain heuristics in the sequential solver.[38]

One drawback of parallel portfolios is the amount of duplicate work. If clause learning is used in the sequential solvers, sharing learned clauses between parallel running solvers can reduce duplicate work and increase performance. Yet, even merely running a portfolio of the best solvers in parallel makes a competitive parallel solver. An example of such a solver is PPfolio.[39][40] It was designed to find a lower bound for the performance a parallel SAT solver should be able to deliver. Despite the large amount of duplicate work due to lack of optimizations, it performed well on a shared memory machine. HordeSat[41] is a parallel portfolio solver for large clusters of computing nodes. It uses differently configured instances of the same sequential solver at its core. Particularly for hard SAT instances HordeSat can produce linear speedups and therefore reduce runtime significantly.

In recent years parallel portfolio SAT solvers have dominated the parallel track of the International SAT Solver Competitions. Notable examples of such solvers include Plingeling and painless-mcomsps.[42]

Divide-and-Conquer

In contrast to parallel portfolios, parallel Divide-and-Conquer tries to split the search space between the processing elements. Divide-and-conquer algorithms, such as the sequential DPLL, already apply the technique of splitting the search space, hence their extension towards a parallel algorithm is straight forward. However, due to techniques like unit propagation, following a division, the partial problems may differ significantly in complexity. Thus the DPLL algorithm typically does not process each part of the search space in the same amount of time, yielding a challenging load balancing problem.[37]

Due to non-chronological backtracking, parallelization of conflict-driven clause learning is more difficult. One way to overcome this is the Cube-and-Conquer paradigm.[43] It suggests solving in two phases. In the "cube" phase the Problem is divided into many thousands, up to millions, of sections. This is done by a look-ahead solver, that finds a set of partial configurations called "cubes". A cube can also be seen as a conjunction of a subset of variables of the original formula. In conjunction with the formula, each of the cubes forms a new formula. These formulas can be solved independently and concurrently by conflict-driven solvers. As the disjunction of these formulas is equivalent to the original formula, the problem is reported to be satisfiable, if one of the formulas is satisfiable. The look-ahead solver is favorable for small but hard problems,[44] so it is used to gradually divide the problem into multiple sub-problems. These sub-problems are easier but still large which is the ideal form for a conflict-driven solver. Furthermore look-ahead solvers consider the entire problem whereas conflict-driven solvers make decisions based on information that is much more local. There are three heuristics involved in the cube phase. The variables in the cubes are chosen by the decision heuristic. The direction heuristic decides which variable assignment (true or false) to explore first. In satisfiable problem instances, choosing a satisfiable branch first is beneficial. The cutoff heuristic decides when to stop expanding a cube and instead forward it to a sequential conflict-driven solver. Preferably the cubes are similarly complex to solve.[43]

Treengeling is an example for a parallel solver that applies the Cube-and-Conquer paradigm. Since its introduction in 2012 it has had multiple successes at the International SAT Solver Competition. Cube-and-Conquer was used to solve the Boolean Pythagorean triples problem.[45]

Local search

One strategy towards a parallel local search algorithm for SAT solving is trying multiple variable flips concurrently on different processing units.[46] Another is to apply the aforementioned portfolio approach, however clause sharing is not possible since local search solvers do not produce clauses. Alternatively, it is possible to share the configurations that are produced locally. These configurations can be used to guide the production of a new initial configuration when a local solver decides to restart its search.[47]

See also

- Unsatisfiable core

- Satisfiability modulo theories

- Counting SAT

- Planar SAT

- Karloff–Zwick algorithm

- Circuit satisfiability

Notes

- The SAT problem for arbitrary formulas is NP-complete, too, since it is easily shown to be in NP, and it cannot be easier than SAT for CNF formulas.

- i.e. at least as hard as every other problem in NP. A decision problem is NP-complete if and only if it is in NP and is NP-hard.

- i.e. such that one literal is not the negation of the other

- viz. all maxterms that can be built with d1,⋯,dk, except d1∨⋯∨dk

- Formally, generalized conjunctive normal forms with a ternary boolean operator R are employed, which is TRUE just if 1 or 3 of its arguments is. An input clause with more than 3 literals can be transformed into an equisatisfiable conjunction of clauses á 3 literals similar to above; i.e. XOR-SAT can be reduced to XOR-3-SAT.

References

- Ohrimenko, Olga; Stuckey, Peter J.; Codish, Michael (2007), "Propagation = Lazy Clause Generation", Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming – CP 2007, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 4741, pp. 544–558, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.70.5471, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74970-7_39,

modern SAT solvers can often handle problems with millions of constraints and hundreds of thousands of variables

. - Hong, Ted; Li, Yanjing; Park, Sung-Boem; Mui, Diana; Lin, David; Kaleq, Ziyad Abdel; Hakim, Nagib; Naeimi, Helia; Gardner, Donald S.; Mitra, Subhasish (November 2010). "QED: Quick Error Detection tests for effective post-silicon validation". 2010 IEEE International Test Conference: 1–10. doi:10.1109/TEST.2010.5699215.

- Karp, Richard M. (1972). "Reducibility Among Combinatorial Problems" (PDF). In Raymond E. Miller; James W. Thatcher (eds.). Complexity of Computer Computations. New York: Plenum. pp. 85–103. ISBN 0-306-30707-3. Here: p.86

- Alfred V. Aho and John E. Hopcroft and Jeffrey D. Ullman (1974). The Design and Analysis of Computer Algorithms. Reading/MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-00029-6. Here: p.403

- Vizel, Y.; Weissenbacher, G.; Malik, S. (2015). "Boolean Satisfiability Solvers and Their Applications in Model Checking". Proceedings of the IEEE. 103 (11): 2021–2035. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2015.2455034.

- Cook, Stephen A. (1971). "The Complexity of Theorem-Proving Procedures" (PDF). Proceedings of the 3rd Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing: 151–158. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.406.395. doi:10.1145/800157.805047.

- Levin, Leonid (1973). "Universal search problems (Russian: Универсальные задачи перебора, Universal'nye perebornye zadachi)". Problems of Information Transmission (Russian: Проблемы передачи информа́ции, Problemy Peredachi Informatsii). 9 (3): 115–116. (pdf) (in Russian), translated into English by Trakhtenbrot, B. A. (1984). "A survey of Russian approaches to perebor (brute-force searches) algorithms". Annals of the History of Computing. 6 (4): 384–400. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1984.10036.

- Alfred V. Aho; John E. Hopcroft; Jeffrey D. Ullman (1974). The Design and Analysis of Computer Algorithms. Addison-Wesley.; here: Thm.10.4

- Aho, Hopcroft, Ullman[8] (1974); Thm.10.5

- Schöning, Uwe (Oct 1999). "A Probabilistic Algorithm for k-SAT and Constraint Satisfaction Problems" (PDF). Proc. 40th Ann. Symp. Foundations of Computer Science. pp. 410–414. doi:10.1109/SFFCS.1999.814612. ISBN 0-7695-0409-4.

- Bart Selman; David Mitchell; Hector Levesque (1996). "Generating Hard Satisfiability Problems". Artificial Intelligence. 81 (1–2): 17–29. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.37.7362. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(95)00045-3.

- Schaefer, Thomas J. (1978). "The complexity of satisfiability problems" (PDF). Proceedings of the 10th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. San Diego, California. pp. 216–226.

- (Schaefer, 1978), p.222, Lemma 3.5

- Buning, H.K.; Karpinski, Marek; Flogel, A. (1995). "Resolution for Quantified Boolean Formulas". Information and Computation. Elsevier. 117 (1): 12–18. doi:10.1006/inco.1995.1025.

- Moore, Cristopher; Mertens, Stephan (2011), The Nature of Computation, Oxford University Press, p. 366, ISBN 9780199233212.

- R. E. Bryant, S. M. German, and M. N. Velev, Microprocessor Verification Using Efficient Decision Procedures for a Logic of Equality with Uninterpreted Functions, in Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods, pp. 1–13, 1999.

- Alhazov, Artiom; Martín-Vide, Carlos; Pan, Linqiang (2003). "Solving a PSPACE-Complete Problem by Recognizing P Systems with Restricted Active Membranes". Fundamenta Informaticae. 58: 67–77.

- Blass, Andreas; Gurevich, Yuri (1982-10-01). "On the unique satisfiability problem". Information and Control. 55 (1): 80–88. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(82)90439-9. ISSN 0019-9958.

- "Complexity Zoo:U - Complexity Zoo". complexityzoo.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- Kozen, Dexter C. (2006). "Supplementary Lecture F: Unique Satisfiability". Theory of Computation. Texts in Computer Science. London: Springer-Verlag. p. 180. ISBN 9781846282973.

- Valiant, L.; Vazirani, V. (1986). "NP is as easy as detecting unique solutions" (PDF). Theoretical Computer Science. 47: 85–93. doi:10.1016/0304-3975(86)90135-0.

- Buldas, Ahto; Lenin, Aleksandr; Willemson, Jan; Charnamord, Anton (2017). Obana, Satoshi; Chida, Koji (eds.). "Simple Infeasibility Certificates for Attack Trees". Advances in Information and Computer Security. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer International Publishing. 10418: 39–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64200-0_3. ISBN 9783319642000.

- Gi-Joon Nam; Sakallah, K. A.; Rutenbar, R. A. (2002). "A new FPGA detailed routing approach via search-based Boolean satisfiability" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems. 21 (6): 674. doi:10.1109/TCAD.2002.1004311.

- Davis, M.; Putnam, H. (1960). "A Computing Procedure for Quantification Theory". Journal of the ACM. 7 (3): 201. doi:10.1145/321033.321034.

- Davis, M.; Logemann, G.; Loveland, D. (1962). "A machine program for theorem-proving" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 5 (7): 394–397. doi:10.1145/368273.368557.

- Zhang, Lintao; Malik, Sharad (2002), "The Quest for Efficient Boolean Satisfiability Solvers", Computer Aided Verification, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 17–36, doi:10.1007/3-540-45657-0_2, ISBN 978-3-540-43997-4

- "An improved exponential-time algorithm for k-SAT", Paturi, Pudlak, Saks, Zani

- "Faster k-SAT algorithms using biased-PPSZ", Hansen, Kaplan, Zamir, Zwick

- Vizel, Y.; Weissenbacher, G.; Malik, S. (2015). "Boolean Satisfiability Solvers and Their Applications in Model Checking". Proceedings of the IEEE. 103 (11): 2021–2035. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2015.2455034.

- Moskewicz, M. W.; Madigan, C. F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Malik, S. (2001). "Chaff: Engineering an Efficient SAT Solver" (PDF). Proceedings of the 38th conference on Design automation (DAC). p. 530. doi:10.1145/378239.379017. ISBN 1581132972.

- Marques-Silva, J. P.; Sakallah, K. A. (1999). "GRASP: a search algorithm for propositional satisfiability" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. 48 (5): 506. doi:10.1109/12.769433.

- http://www.cril.univ-artois.fr/~jabbour/manysat.htm

- "The international SAT Competitions web page". Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- "SAT Competition 2016". baldur.iti.kit.edu. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "SAT Competition 2017". baldur.iti.kit.edu. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "SAT Competition 2018". sat2018.forsyte.tuwien.ac.at. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- Balyo, Tomáš; Sinz, Carsten (2018), "Parallel Satisfiability", Handbook of Parallel Constraint Reasoning, Springer International Publishing, pp. 3–29, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-63516-3_1, ISBN 978-3-319-63515-6

- Biere, Armin. "Lingeling, Plingeling, PicoSAT and PrecoSAT at SAT Race 2010" (PDF). SAT-RACE 2010.

- "ppfolio solver". www.cril.univ-artois.fr. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- "SAT 2011 Competition: 32 cores track: ranking of solvers". www.cril.univ-artois.fr. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- Balyo, Tomáš; Sanders, Peter; Sinz, Carsten (2015), "HordeSat: A Massively Parallel Portfolio SAT Solver", Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer International Publishing, pp. 156–172, arXiv:1505.03340, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24318-4_12, ISBN 978-3-319-24317-7

- "SAT Competition 2018". sat2018.forsyte.tuwien.ac.at. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- Heule, Marijn J. H.; Kullmann, Oliver; Wieringa, Siert; Biere, Armin (2012), "Cube and Conquer: Guiding CDCL SAT Solvers by Lookaheads", Hardware and Software: Verification and Testing, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 50–65, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-34188-5_8, ISBN 978-3-642-34187-8

- Heule, Marijn J. H.; van Maaren, Hans (2009). "Look-Ahead Based SAT Solvers" (PDF). Handbook of Satisfiability. IOS Press. pp. 155–184. ISBN 978-1-58603-929-5.

- Heule, Marijn J. H.; Kullmann, Oliver; Marek, Victor W. (2016), "Solving and Verifying the Boolean Pythagorean Triples Problem via Cube-and-Conquer", Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing – SAT 2016, Springer International Publishing, pp. 228–245, arXiv:1605.00723, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40970-2_15, ISBN 978-3-319-40969-6

- Roli, Andrea (2002), "Criticality and Parallelism in Structured SAT Instances", Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming - CP 2002, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2470, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 714–719, doi:10.1007/3-540-46135-3_51, ISBN 978-3-540-44120-5

- Arbelaez, Alejandro; Hamadi, Youssef (2011), "Improving Parallel Local Search for SAT", Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 46–60, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-25566-3_4, ISBN 978-3-642-25565-6

References are ordered by date of publication:

- Michael R. Garey & David S. Johnson (1979). Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1045-5. A9.1: LO1 – LO7, pp. 259 – 260.

- Marques-Silva, J.; Glass, T. (1999). "Combinational equivalence checking using satisfiability and recursive learning" (PDF). Design, Automation and Test in Europe Conference and Exhibition, 1999. Proceedings (Cat. No. PR00078). p. 145. doi:10.1109/DATE.1999.761110. ISBN 0-7695-0078-1.

- Clarke, E.; Biere, A.; Raimi, R.; Zhu, Y. (2001). "Bounded Model Checking Using Satisfiability Solving". Formal Methods in System Design. 19: 7–34. doi:10.1023/A:1011276507260.

- Giunchiglia, E.; Tacchella, A. (2004). Giunchiglia, Enrico; Tacchella, Armando (eds.). Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2919. doi:10.1007/b95238. ISBN 978-3-540-20851-8.

- Babic, D.; Bingham, J.; Hu, A. J. (2006). "B-Cubing: New Possibilities for Efficient SAT-Solving" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. 55 (11): 1315. doi:10.1109/TC.2006.175.

- Rodriguez, C.; Villagra, M.; Baran, B. (2007). "Asynchronous team algorithms for Boolean Satisfiability" (PDF). 2007 2nd Bio-Inspired Models of Network, Information and Computing Systems. pp. 66–69. doi:10.1109/BIMNICS.2007.4610083.

- Carla P. Gomes; Henry Kautz; Ashish Sabharwal; Bart Selman (2008). "Satisfiability Solvers". In Frank Van Harmelen; Vladimir Lifschitz; Bruce Porter (eds.). Handbook of knowledge representation. Foundations of Artificial Intelligence. 3. Elsevier. pp. 89–134. doi:10.1016/S1574-6526(07)03002-7. ISBN 978-0-444-52211-5.

- Vizel, Y.; Weissenbacher, G.; Malik, S. (2015). "Boolean Satisfiability Solvers and Their Applications in Model Checking". Proceedings of the IEEE. 103 (11): 2021–2035. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2015.2455034.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boolean satisfiability problem. |

- SAT Game - try solving a Boolean satisfiability problem yourself

SAT problem format

A SAT problem is often described in the DIMACS-CNF format: an input file in which each line represents a single disjunction. For example, a file with the two lines

1 -5 4 0 -1 5 3 4 0

represents the formula "(x1 ∨ ¬x5 ∨ x4) ∧ (¬x1 ∨ x5 ∨ x3 ∨ x4)".

Another common format for this formula is the 7-bit ASCII representation "(x1 | ~x5 | x4) & (~x1 | x5 | x3 | x4)".

- BCSAT is a tool that converts input files in human-readable format to the DIMACS-CNF format.

Online SAT solvers

- BoolSAT – Solves formulas in the DIMACS-CNF format or in a more human-friendly format: "a and not b or a". Runs on a server.

- Logictools – Provides different solvers in javascript for learning, comparison and hacking. Runs in the browser.

- minisat-in-your-browser – Solves formulas in the DIMACS-CNF format. Runs in the browser.

- SATRennesPA – Solves formulas written in a user-friendly way. Runs on a server.

- somerby.net/mack/logic – Solves formulas written in symbolic logic. Runs in the browser.

Offline SAT solvers

- MiniSAT – DIMACS-CNF format and OPB format for its companion Pseudo-Boolean constraint solver MiniSat+

- Lingeling – won a gold medal in a 2011 SAT competition.

- PicoSAT – an earlier solver from the Lingeling group.

- Sat4j – DIMACS-CNF format. Java source code available.

- Glucose – DIMACS-CNF format.

- RSat – won a gold medal in a 2007 SAT competition.

- UBCSAT. Supports unweighted and weighted clauses, both in the DIMACS-CNF format. C source code hosted on GitHub.

- CryptoMiniSat – won a gold medal in a 2011 SAT competition. C++ source code hosted on GitHub. Tries to put many useful features of MiniSat 2.0 core, PrecoSat ver 236, and Glucose into one package, adding many new features

- Spear – Supports bit-vector arithmetic. Can use the DIMACS-CNF format or the Spear format.

- HyperSAT – Written to experiment with B-cubing search space pruning. Won 3rd place in a 2005 SAT competition. An earlier and slower solver from the developers of Spear.

- BASolver

- ArgoSAT

- Fast SAT Solver – based on genetic algorithms.

- zChaff – not supported anymore.

- BCSAT – human-readable boolean circuit format (also converts this format to the DIMACS-CNF format and automatically links to MiniSAT or zChaff).

- gini – Go language SAT solver with related tools.

- gophersat – Go language SAT solver that can also deal with pseudo-boolean and MAXSAT problems.

- CLP(B) – Boolean Constraint Logic Programming, for example SWI-Prolog.

SAT applications

- WinSAT v2.04: A Windows-based SAT application made particularly for researchers.

Benchmarks

SAT solving in general:

Evaluation of SAT solvers

- Yearly evaluation of SAT solvers

- SAT solvers evaluation results for 2008

- International SAT Competitions

- History

More information on SAT:

This article includes material from a column in the ACM SIGDA e-newsletter by Prof. Karem Sakallah

Original text is available here