Boeing 737 MAX

The Boeing 737 MAX is the fourth generation of the Boeing 737, a narrow-body airliner manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes (BCA). It succeeds the Boeing 737 Next Generation (NG). It is based on earlier 737 designs, re-engined with more efficient CFM International LEAP-1B engines, aerodynamic changes, which include its distinctive split-tip winglets, and airframe modifications.[10]

| Boeing 737 MAX | |

|---|---|

| |

| The 737 MAX is a fourth generation Boeing 737, re-engined with CFM LEAP turbofans. | |

| Role | Narrow-body twin-engine jet airliner |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing Commercial Airplanes |

| First flight | January 29, 2016[1] |

| Introduction | May 22, 2017 with Malindo Air[2] |

| Status | Grounded worldwide;[3] deliveries suspended |

| Primary users | Southwest Airlines American Airlines Air Canada China Southern Airlines |

| Produced | 2014[4]-present[lower-alpha 1] |

| Number built | 387 delivered to customers as of March 2019[6] approx. 400 produced and stored as of Dec. 2019[7] |

| Program cost | Airframe only: $1–1.8 billion; including engine development: $2–3B[8] |

| Unit cost |

MAX 7: US$99.7 million MAX 8: US$121.6M MAX 200: US$124.8M MAX 9: US$128.9M MAX 10: US$134.9M as of 2019[9] |

| Developed from | Boeing 737 Next Generation |

The new series was publicly announced on August 30, 2011.[11] The 737 MAX took its maiden flight on January 29, 2016[1] and the series gained FAA certification in March 2017.[12][10] The first delivery was a MAX 8 in May 2017, to Malindo Air,[13] with whom it commenced service on May 22, 2017.[2]

The 737 MAX series has been offered in four variants, offering 138 to 204 seats in typical two-class configuration[14] and a 3,215 to 3,825 nmi (5,954 to 7,084 km) range. The 737 MAX 7, MAX 8 (including the denser, 200–seat MAX 200), and MAX 9 are intended to replace the 737-700, -800, and -900, respectively.[10] Additional length is offered with the further stretched 737 MAX 10. As of December 2019, the Boeing 737 MAX had received 4,932 firm orders and delivered 387 aircraft.[6]

In the aftermath of two fatal accidents, Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, the Boeing 737 MAX was grounded worldwide in March 2019. Boeing is implementing changes to its flight control system and pilot training, and expects the airliner to be flying again by mid-2020.[3][15] Boeing subsequently suspended production in January 2020 with approximately 400 MAX airplanes awaiting delivery, with production resuming in May 2020 at a low rate.[16][5]

Development

Background

In 2006, Boeing started considering the replacement of the 737 with a "clean-sheet" design that could follow the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.[17] In June 2010, a decision on this replacement was postponed into 2011.[18]

On December 1, 2010, Boeing's competitor, Airbus, launched the Airbus A320neo family to improve fuel burn and operating efficiency with new engines: the CFM International LEAP and Pratt & Whitney PW1000G.[19] In February 2011, Boeing's CEO Jim McNerney maintained "We're going to do a new airplane."[20] In March 2011, BCA President James Albaugh told participants of a trade meeting the company was not sure about a 737 re-engine, like Boeing CFO James A. Bell stated at an investor conference the same month.[21] The A320neo gathered 667 commitments at the June 2011, Paris Air Show for a backlog of 1,029 units since its launch, setting an order record for a new commercial airliner.[22]

On July 20, 2011, American Airlines announced an order for 460 narrowbody jets including 130 A320ceos and 130 A320neos, and intended to order 100 re-engined 737s with CFM LEAPs, pending Boeing confirmation.[23] The order broke Boeing's monopoly with the airline and forced Boeing into a re-engined 737.[24] As this sale included a Most-Favoured-Customer Clause, Airbus has to refund any difference to American if it sells to another airline at a lower price, so the European manufacturer cannot give a competitive price to competitor United Airlines, leaving it to a Boeing-skewed fleet.[25]

Program launch

On August 30, 2011, Boeing's board of directors approved the launch of the re-engined 737, expecting a fuel burn 4% lower than the A320neo.[11] Studies for additional drag reduction were performed during 2011, including revised tail cone, natural laminar flow nacelle, and hybrid laminar flow vertical stabilizer.[26] Boeing abandoned the development of a new design.[27] Boeing expected the 737 MAX to meet or exceed the range of the Airbus A320neo.[28] Firm configuration for the 737 MAX was scheduled for 2013.[29]

In March 2010, the estimated cost to re-engine the 737 according to Mike Bair, Boeing Commercial Airplanes' vice president of business strategy & marketing, would be $2–3 billion including the CFM engine development. During Boeing's Q2 2011 earnings call, former CFO James Bell said the development cost for the airframe only would be 10–15% of the cost of a new program estimated at $10–12 billion at the time. Bernstein Research predicted in January 2012, that this cost would be twice that of the Airbus A320neo.[8] The MAX development cost could have been well over the $2bn internal target and closer to $4bn.[30] Fuel consumption is reduced by 14% from the 737NG.[31]

In November 2014, Boeing Chief Executive Officer Jim McNerney said the 737 will be replaced by a new airplane by 2030, slightly bigger and with new engines but keeping its general configuration, probably a composite airplane.[32]

Production

.jpg)

On August 13, 2015, the first 737 MAX fuselage completed assembly at Spirit Aerosystems in Wichita, Kansas, for a test aircraft that would eventually be delivered to launch customer Southwest Airlines.[33] On December 8, 2015, the first 737 MAX—a MAX 8 named Spirit of Renton—was rolled out at the Boeing Renton Factory.[34][35]

Because GKN could not produce the titanium honeycomb inner walls for the thrust reversers quickly enough, Boeing switched to a composite part produced by Spirit to deliver 47 MAXs per month in 2017. Spirit supplies 69% of the 737 airframe, including the fuselage, thrust reverser, engine pylons, nacelles, and wing leading edges.[36]

A new spar-assembly line with robotic drilling machines should increase throughput by 33%. The Electroimpact automated panel assembly line sped up the wing lower-skin assembly by 35%.[37] Boeing planned to increase its 737 MAX monthly production rate from 42 planes in 2017, to 57 planes by 2019.[38] The new spar-assembly line is designed by Electroimpact.[39] Electroimpact has also installed fully automated riveting machines and tooling to fasten stringers to the wing skin.[40]

The rate increase strained the production and by August 2018, over 40 unfinished jets were parked in Renton, awaiting parts or engine installation, as CFM engines and Spirit fuselages were delivered late.[41] After parked airplanes peaked at 53 at the beginning of September, Boeing reduced this by nine the following month, as deliveries rose to 61 from 29 in July and 48 in August.[42]

On September 23, 2015, Boeing announced a collaboration with Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China Ltd. to build a completion and delivery facility for the 737,[43] in Zhoushan, China,[44] the first outside the U.S.[45] This facility initially handles interior finishing only, but will subsequently be expanded to include paintwork. The first aircraft was delivered from the facility to Air China on December 15, 2018.[46]

The largest part of the suppliers cost are the aerostructures with US$10–12M (35-34% of the US$ 28.5-35 M total), followed by the engines with US$7–9M (25-26%), systems and interiors with US$5–6M each (18-17%), then avionics with US$1.5-2M (5-6%).[47]

Flight testing and certification

The first flight took place on January 29, 2016, at Renton Municipal Airport,[48] nearly 49 years after the maiden flight of the original 737-100, on April 9, 1967.[1] The first MAX 8, 1A001, was used for aerodynamic trials: flutter testing, stability and control, and takeoff performance-data verification, before it was modified for an operator and delivered. 1A002 was used for performance and engine testing: climb and landing performance, crosswind, noise, cold weather, high altitude, fuel burn and water-ingestion. Aircraft systems including autoland were tested with 1A003. 1A004, with an airliner layout, flew function-and-reliability certification for 300h with a light flight-test instrumentation.[49]

The 737 MAX gained Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification on March 8, 2017.[12] It was approved by the EASA on March 27, 2017.[50] After completing 2,000 test flight hours and 180-minute ETOPS testing requiring 3,000 simulated flight cycles in April 2017, CFM International notified Boeing of a possible manufacturing quality issue with low pressure turbine (LPT) discs in LEAP-1B engines.[51] Boeing suspended 737 MAX flights on May 4,[13] and resumed flights on May 12.[52]

During the certification process, the FAA delegated many evaluations to Boeing, allowing the manufacturer to review their own product.[48][53] It was widely reported that Boeing pushed to expedite approval of the 737 MAX to compete with the Airbus A320neo, which hit the market nine months ahead of Boeing's model.[54]

Introduction

.jpg)

The first delivery was a MAX 8, handed over to Malindo Air (a subsidiary of Lion Air) on May 16, 2017; it entered service on May 22.[2] Norwegian Air subsidiary Norwegian Air International was the second airline to put a 737 MAX into service, when it performed its first transatlantic flight with a MAX 8 named Sir Freddie Laker on July 15, 2017, between Edinburgh Airport in Scotland and Bradley International Airport in the US state of Connecticut, followed by a second rotation from Edinburgh to Stewart Airport, New York.[55]

Boeing aimed to match the 99.7% dispatch reliability of the 737 Next Generation (NG).[56] Southwest Airlines, the launch customer, took delivery of its first 737 MAX on August 29, 2017.[57] Boeing planned to deliver at least 50 to 75 aircraft in 2017, 10–15% of the more than 500 737s to be delivered in the year.[13]

After one year of service, 130 MAXs had been delivered to 28 customers, logging over 41,000 flights in 118,000 hours and flying over 6.5 million passengers. flydubai observed 15% more efficiency than the NG, more than the 14% promised, and dependability reached 99.4%. Long routes include 24 over 2,500 nmi (4,630 km), including a daily Aerolineas Argentinas service from Buenos Aires to Punta Cana over 3,252 nmi (6,023 km).[58]

Before the 737 MAX was grounded by FAA, and without taking into account of disruptions following the second Boeing 737 Max 8 crash, Moody's estimated in 2019 that, because of the high production volume, the resulting efficiencies and the amortization of the capital investment over the program's decades, Boeing's operating margin at $12–15 million on each 737 Max 8 delivered, while the $121.6 million list price is usually discounted by 50-55%.[59][60] After the grounding and suspension of production of the 737 MAX, Boeing estimated it would cost an additional $6.3 billion to produce the aircraft in the 737 MAX program, in addition to an estimated $8.3 billion for concession and compensation to customers for disruptions caused by the grounding and delivery delays of 737 MAX and $4 billion "future abnormal costs" as production of MAX is slowly restarted.[61][62] The increased program costs will reduce the margin of the 737 program in the future.[62][63] Moody’s also cut Boeing’s debt ratings citing the rising costs due to grounding and the production halt.[64]

Boeing found foreign object debris in the fuel tanks of 35 of 50 grounded 737 MAX aircraft that were inspected, and is to check the remainder of the 400 undelivered planes.[65] Boeing had similar issues with 787s produced in South Carolina.[66]

Grounding and suspension of production

In March 2019, the Boeing 737 MAX passenger airliner was grounded worldwide after 346 people died in two crashes, Lion Air Flight 610 on October 29, 2018 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on March 10, 2019. Ethiopian Airlines immediately grounded its remaining fleet of the aircraft type. On March 11, the Civil Aviation Administration of China ordered the first nationwide grounding, followed by most other aviation authorities in quick succession. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) publicly affirmed the airworthiness of the airplane on March 11, but grounded it on March 13 after receiving evidence of accident similarities. All 387 aircraft, which served 8,600 flights per week for 59 airlines, were barred from service by March 18, 2019.

In November 2018, a week after the Lion Air accident, Boeing revealed the existence of a new automated flight control on the MAX, the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), which could force the aircraft into nosedives. Boeing had not explained the system in crew manuals or training. Boeing and the FAA required an immediate addition to the manual to describe the function and a recovery procedure. In December 2018, the FAA privately predicted that MCAS could cause more accidents, but assumed the updated manual would suffice until Boeing fixed the system.

During the groundings, FAA certification of the MAX was investigated by the U.S. Congress, Transportation Department, FBI and ad hoc panels. The inquiries examined the FAA's longstanding practice of delegating substantial self-approval authority to Boeing. Investigations found evidence that Boeing put undue pressure on employees performing safety assurance work on behalf of the FAA, and also uncovered several systems and manufacturing defects. The Indonesian NTSC accident report blamed certification, maintenance, and flight crew actions. The Ethiopian ECAA determined that the flight crew had attempted the recovery procedure, and both authorities faulted flaws in aircraft design. The U.S. NTSB said Boeing failed to assess the consequences of MCAS failure and made incorrect assumptions about flight crew response. The U.S. House of Representatives criticized Boeing's "culture of concealment" during certification and in the aftermath of both accidents. The FAA revoked Boeing's authority to issue airworthiness certificates for individual MAX airplanes.

In January 2020, Boeing reversed its policy and recommended flight simulator training for all MAX pilots, and temporarily halted production of the MAX until May 2020. A total of 400 aircraft await certification and delivery to airlines when the grounding is lifted. The longest ever grounding of a U.S. airliner was estimated to have cost Boeing $18.6 billion by March 2020; return to service was subject to further delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. By June 2020, airlines and leasing companies had canceled nearly 600 orders for the MAX.

Production slowdown and suspension

From mid-April 2019, the company announced it was temporarily cutting production of the 737 aircraft from 52 per month to 42 amid the Boeing 737 MAX groundings.[67] Production of the LEAP-1B engine continued at an unchanged rate, enabling CFM to catch up its backlog within a few weeks.[68]

As the 737 MAX re-certification moved into 2020, Boeing suspended production from January to conserve cash and prioritize stored aircraft delivery.[69][16] The 737 MAX program was Boeing's largest source of profit.[70] Around 80% of the 737 production costs involve payments to parts suppliers, which may be as low as US$10 million per plane.[71] After the announcement, Moody’s cut Boeing’s debt ratings in December 2019, citing the rising costs due to the grounding and the production halt including financial support to suppliers and compensation to airlines and lessors which could lower the program’s margins and cash generation for years.[64] Moody's also warned the production halt would have wide and harmful impact to the whole aerospace and defense supply chain and, if and when production resumes, the ramp up would be slower than previously anticipated, as suppliers have to make adjustments to cost structures built for planned record output on the 737 program.[72]

CFM International reduced production of the 737 MAX's CFM LEAP-1B, in favor of the A320neo's LEAP-1A, but is prepared to meet demand for both aircraft.[73] Boeing has not said publicly how long the suspension will last. The last pre-suspension fuselages entered final assembly in early January 2020. Boeing, internally, may expect production to be halted for at least 60 days.[74] Industry observers began to question if Boeing's projection of record production rate of 57 per month would ever be reached.[75] In early January 2020, an issue was discovered in the software update, further delaying the return to service. The FAA is unlikely to approve the return until March. Several major U.S. airlines have extended cancellations of MAX flights until early June.[76]

In late January, production was expected to restart in April and take a year and a half to clear the inventory of 400 airplanes, ramp up slowly and build over time: Boeing might have delivered 180 stored jets by year-end and produce an equal number.[77] Boeing did not disclose any possible effect on deliveries caused by the FAA's withdrawal of Boeing's delegated authority to certify the airworthiness of each aircraft.[78] MAX supplier Spirit AeroSystems said it does not expect to return production rate to 52 per month until late 2022.[79] By early April, the COVID-19 pandemic led Boeing to shut down its other airliner production lines[80] and further delayed recertification of the MAX.[81] By late April 2020, Boeing signaled it hoped to win regulatory approval by August 2020.[82] On May 27, 2020, Boeing resumed 737 MAX production at a low production rate, as it will be ramped up according to customer deliveries, towards 31 monthly in 2021.[5]

Design

In mid-2011, the objective was to match the A320neo's 15% fuel burn advantage. The initial reduction was 10–12%; it was later enhanced to 14.5%. The fan was widened from 61 in (150 cm) to 69.4 in (176 cm) by raising the nose gear and placing the engine higher and forward. The split winglet added 1–1.5%, a re-lofted tail cone 1% more. Electronically controlling the bleed air system improved efficiency. The new engine casings included chevrons similar to the 787 to help reduce engine noise.[83]

Aerodynamic changes

The split tip wingtip device is designed to maximize lift while staying in the same ICAO Aerodrome Reference Code letter C gates as current 737s. It traces its design to the McDonnell Douglas MD-12 1990s twin-deck concept, proposed for similar gate restrictions before the Boeing merger.[84] A MAX 8 with 162 passengers on a 3,000 nmi (5,600 km) flight is to have up to a 1.8% better fuel burn than a blended-winglet-equipped aircraft and 1% over 500 nmi (930 km) at Mach 0.79.[84]

The new winglet is 9 ft 6 in (2.90 m) high.[37] Other improvements include a re-contoured tail cone, revised auxiliary power unit inlet and exhaust, aft-body vortex generators removal and other small aerodynamic improvements.[31] Aviation Partners offers a similar "Split-Tip Scimitar" winglet for previous 737NGs.[85] It resembles a three-way hybrid between a blended winglet, wingtip fence, and raked wingtip.

Structural and other changes

The 8 in (20 cm) taller nose-gear strut keeps the same 17-inch (43 cm) ground clearance of the engine nacelles.[31] New struts and nacelles for the heavier engines add bulk, the main landing gear and supporting structure are beefier, and fuselage skins are thicker in some places for a 6,500 lb (2,900 kg) increase to the MAX 8's empty aircraft weight.[31] To preserve fuel and payload capacity, its maximum takeoff weight is 7,000 lb (3,200 kg) heavier.[31]

Rockwell Collins will supply four 15.1-inch (380 mm) landscape liquid crystal displays (LCD), as used on the 787 Dreamliner, to improve pilots' situation awareness and efficiency.[86] Boeing plans no major modifications for the 737 MAX flight deck, as it wants to maintain commonality with the 737 Next Generation family. Boeing Commercial Airplanes CEO Jim Albaugh said in 2011, that adding more fly-by-wire control systems would be "very minimal".[87] Most of the systems are carried from the 737NG for a short differences-training course to upgrade flight crews.[31]

The 737 MAX extended spoilers are fly-by-wire controlled.[37] As production standard, the 737 MAX will feature the Boeing Sky Interior with overhead bins and LED lighting based on the Boeing 787's interior.[88]

The automatic stabilizer control system has been enhanced to include Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) in addition to Speed Trim System (STS). Compared to STS, MCAS has greater authority and cannot be disengaged with the aft and forward column cutout switches. The center console stabilizer trim cutout switches have been re-wired compared to the previous versions of the 737 to the effect that automatic stabilizer trim control functions cannot be turned off while retaining electric trim switches functionality.[89]

Engines

.jpg)

In 2011, the Leap-1B was initially 10–12% more efficient than the previous 156 cm (61 in) CFM56-7B of the 737NG.[26] The 18-blade, woven carbon-fiber fan enables a 9:1 bypass ratio (up from 5.1:1 with the previous 24-blade titanium fan) for a 40% smaller noise footprint.[31] The CFM56 bypass ranges from 5.1:1 to 5.5:1.[90] The two-shaft design has a low-pressure section comprising the fan and three booster stages driven by five axial turbine stages and a high-pressure section with a 10-stage axial compressor driven by a two-stage turbine.[31] The 41:1 overall pressure ratio, increased from 28:1, and advanced hot-section materials enabling higher operating temperatures permit a 15% reduction in thrust specific fuel consumption (TSFC) along with 20% lower carbon emissions, 50% lower nitrogen-oxide emissions, though each engine weighs 849 lb (385 kg) more at 6,129 lb (2,780 kg).[31]

In August 2011, Boeing had to choose between 66 in (168 cm) or 68 in (173 cm) fan diameters necessitating landing gear changes to maintain a 17-inch (43 cm) ground clearance beneath the new engines; Boeing Commercial Airplanes chief executive officer Jim Albaugh stated "with a bigger fan you get more efficiency because of the bypass ratio [but also] more weight and more drag", with more airframe changes.[91] The smaller Leap-1B engine will weigh less and have a lower frontal area but a lower bypass ratio leading to a higher thrust specific fuel consumption than the 78 in (200 cm) Leap-1A of the A320neo.

In November 2011, Boeing selected the larger fan diameter, necessitating a 6–8 in (150–200 mm) longer nose landing gear.[92][93] In May 2012, Boeing further enlarged the fan to 69.4 in (176 cm), paired with a smaller engine core within minor design changes before the mid-2013 final configuration.[94][95]

The nacelle features chevrons for noise reduction like the 787.[96] A new bleed air digital regulator will improve its reliability.[97] The new nacelles being larger and more forward possess aerodynamic properties which act to further increase the pitch rate. The larger engine is cantilevered ahead of and slightly above the wing, and the laminar flow engine nacelle lipskin is a GKN Aerospace one-piece, spun-formed aluminum sheet inspired by the 787.[37]

To mitigate the pitch-up tendency of the new flight geometry from the engines being located further forward and higher than previous engines, Boeing added the new Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System.[98]

Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS)

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) is a flight control law (software) on the Boeing 737 MAX intended to mimic pitching behavior similar to aircraft in the previous generation of the series, the Boeing 737 NG. MCAS was first deployed on the Boeing KC-46 Air Force tanker, where it "similarly moves the stabilizer in a wind-up turn".[99] Unlike the 737 MAX, however, MCAS could be overridden on the KC-46 by pulling back on its control column. MCAS on the MAX was designed to activate using input from only one of the airplane's two angle of attack sensors, making the system susceptible to a single point of failure. MCAS adjusts the horizontal stabilizer trim to push the nose down when the aircraft is operating in manual flight, with flaps up, at an elevated angle of attack (AoA), so the pilot will not inadvertently pull the airplane up too steeply, potentially causing a stall.

Boeing did not include a description of MCAS in the MAX flight manuals, leaving pilots unaware of the system when the airplane entered service.[100] On November 10, 2018, twelve days after Lion Air Flight 610 crash, Boeing publicly revealed the existence of MCAS on the 737 MAX was in a message to airline operators and other aviation interests.[101] Contrary to descriptions in news reports, however, Boeing claims that MCAS is not an anti-stall system.

Boeing had also been aware that the system contained numerous deficiencies, that suppressed a crucial AoA disagree message. The Wall Street Journal reported that Boeing failed to share information about that issue for "about a year" before the Lion Air crash in Indonesia.[102] With no knowledge of MCAS and its behavior, the pilots of the Lion Air flight, the first to crash, were at a disadvantage when attempting to respond to the system's erroneous activation. Yet, a recovery procedure highlighted by Boeing and the FAA failed to prevent the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, which led to the global grounding of all 737 MAX aircraft pending investigations and software fixes. In April 2019, Boeing admitted that MCAS played a role in both accidents.

Variants

The 737-700, -800 and -900ER, the most widespread versions of the previous 737NG,[6] are succeeded by the 737 MAX 7, MAX 8 and MAX 9, respectively[103] (FAA type certificate: 737-7, -8, and -9[12]). The 737 MAX 8 entered service in May 2017,[2] and the MAX 9 entered service in March 2018.[104] The MAX 7 and MAX 200 (a higher density version of the MAX 8) were expected to enter service in 2019,[105][106] and the MAX 10 in 2020.[107]

In February 2018, Boeing forecast that 60–65% of demand for the airliner would be for the 737 MAX 8 variant, 20–25% for the MAX 9 and MAX 10, and 10% for the MAX 7.[108]

737 MAX 7

.jpg)

Originally based on the 737-700, Boeing announced the redesign of the MAX 7 derived from the MAX 8 at the July 2016 Farnborough Air Show, accommodating two more seat rows than the 737-700 for 138 seats, up 12 seats.[109][110] The redesign uses the 737-8 wing and landing gear; a pair of over-wing exits rather than the single-door configuration; a 46-inch longer aft fuselage and a 30-inch longer forward fuselage; structural re-gauging and strengthening; and systems and interior modifications to accommodate the longer length.[111] It is to fly 1,000 nmi (1,900 km) farther than the -700 with 18% lower fuel costs per seat. Boeing predicts the MAX 7 to carry 12 more passengers 400 nmi (740 km) farther than A319neo with 7% lower operating costs per seat.[112] Boeing plans to improve its range from 3,850 nmi (4,430 mi; 7,130 km) to 3,915 nmi (4,505 mi; 7,251 km) after 2021.[113]

Production on the first 65-foot-long (20 m) wing spar for the 737-7 began in October 2017.[107] Assembly of the first flight-test aircraft began on November 22, 2017[114] and was rolled out of the factory on February 5, 2018.[115] The MAX 7 took off for its first flight on March 16, 2018, from the factory in Renton, Washington and flew for three hours over Washington state.[116] It reached 250 kn (460 km/h) and 25,000 ft (7,600 m), performed a low approach, systems checks and an inflight engine restart, and landed in Moses Lake, Washington, Boeing's flight test center.[117]

Entry into service with launch operator Southwest Airlines was expected in January 2019,[107] but the airline deferred these orders until 2023–2024.[118] WestJet also converted its order for MAX 7s, originally due for delivery in 2019, into MAX 8s and is not expected to take any MAX 7s until at least 2021.[119] Customers for the aircraft include Southwest Airlines (30), WestJet (23), Canada Jetlines (5) and ILFC Aviation (5).[6] The MAX 7 seems to have fewer than 100 orders among over 4,300 MAX total sales.[112]

737 MAX 8

.jpg)

The first variant developed in the 737 MAX series, the MAX 8 replaces the 737-800 with a longer fuselage than the MAX 7. Boeing plans to improve its range from 3,515 nmi (4,045 mi; 6,510 km) to 3,610 nmi (4,150 mi; 6,690 km) after 2021.[113] On July 23, 2013, Boeing completed the firm configuration for the 737 MAX 8.[120] The MAX 8 has a lower empty weight and higher maximum takeoff weight than the A320neo. During a test flight conducted for Aviation Week, while cruising at a true airspeed of 449 kn (832 km/h) and a weight of 140,500 lb (63,700 kg), at a lower than optimal altitude (FL350 vs. the preferred FL390) and with an "unusually far forward" center of gravity, the test aircraft consumed 4,460 lb (2,020 kg) of fuel per hour.[31]

The Boeing 737 MAX 8 completed its first flight testing in La Paz, Bolivia. The 13,300-foot altitude at El Alto International Airport tested the MAX's capability to take off and land at high altitudes.[121] Its first commercial flight was operated by Malindo Air on May 22, 2017, between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore as Flight OD803.[2] In early 2017, a new -8 was valued at $52.85 million, rising to below $54.5 million by mid 2018.[122]

737 MAX 200

In September 2014, Boeing launched a high-density version of the 737 MAX 8, the 737 MAX 200, named for seating for up to 200 passengers in a single-class high-density configuration with slimline seats; an extra pair of exit doors is required because of the higher passenger capacity. Boeing states that this version would be 20% more cost-efficient per seat than current 737 models, and would be the most efficient narrow-body on the market when delivered, including 5% lower operating costs than the 737 MAX 8.[123][124] Three of eight galley trolleys are removed to accommodate more passenger space.[125] An order with Ryanair for 100 aircraft was finalized in December 2014.[126] The variant is officially designated 737-8200.[127]

In mid-November 2018, the first of the 135 ordered by Ryanair rolled out, in a 197-seat configuration.[128] It was first flown from Renton on January 13, 2019,[129] and was due to enter service in April 2019, with four further MAX 200s expected later in 2019,[130] though these deliveries were deferred while the MAX is grounded; Ryanair has stated that it intends to place a further order once flights resume.[131] In November 2019, Ryanair informed its pilots that, due to an unspecified design issue with the additional over-wing exit doors, it did not expect to receive any MAX 200s until late April or early May 2020, with "at best" 10 aircraft in service for the peak summer season.[132]

Proposed 737-8ERX

Airlines have been shown a 737-8ERX concept based on the 737 MAX 8 with a higher 194,700 lb (88.3 t) maximum take-off weight using wings, landing gear and central section from the MAX 9 to provide a longer range of 4,000 nautical miles (4,600 mi; 7,400 km) with seating for 150, closer to the Airbus A321LR.[133]

737 MAX 9

.jpg)

The 737 MAX 9 will replace the 737-900 and has a longer fuselage than the MAX 8. Boeing plans to improve its range from 3,510 nmi (4,040 mi; 6,500 km) to 3,605 nmi (4,149 mi; 6,676 km) after 2021.[113] Lion Air is the launch customer with an order for 201 in February 2012.[37] It made its roll-out on March 7, 2017, and first flight on April 13, 2017;[134] it took off from Renton Municipal Airport and landed at Boeing Field after a 2 hr 42 min flight.[135] It was presented at the 2017 Paris Air Show.[136]

Boeing 737-9 flight tests were scheduled to run through 2017, with 30% of the -8 tests repeated; aircraft 1D001 was used for auto-land, avionics, flutter, and mostly stability-and-control trials, while 1D002 was used for environment control system testing.[49] It was certified by February 2018.[137] Asian low-cost carrier Lion Air Group took delivery of the first on March 21, 2018, before entering service with Thai Lion Air.[104] As the competing A321neo attracts more orders, the value of 737-9 is the same as a 2018 737-8 at $53 million.[138]

737 MAX 10

To compete with the Airbus A321neo, loyal customers such as Korean Air and United Airlines pressed Boeing to develop a larger variant than the MAX 9, of which Boeing revealed studies in early 2016.[139] As the A321neo had outsold the MAX 9 five-to-one, the proposed MAX 10 included a larger engine, stronger wing, and telescoping landing gear in mid-2016.[140] In September 2016, it was reported that the variant would be simpler and lower-risk with a modest stretch of 6–7 ft (1.83–2.13 m) for a length of 143–144 ft (43.6–43.9 m), seating 12–18 more passengers for 192-198 in a dual-class layout or 226-232 for a single class, needing an uprated 31,000 lbf (140 kN) CFM LEAP-1B that could be available by 2019, or 2020, and would likely require a landing-gear modification to move the rotation point slightly aft.[141]

In October 2016, Boeing's board of directors granted authority to offer the stretched variant with two extra fuselage sections forward and aft with a 3,100 nautical miles (3,600 mi; 5,700 km) range reduced from 3,300 nautical miles (3,800 mi; 6,100 km) of the -9.[139] In early 2017, Boeing showed a 66 in (1.7 m) stretch to 143 feet (44 m), enabling seating for 230 in a single class or 189 in two-class capacity, compared to 193 in two-class seating for the A321neo. The modest stretch of the MAX 10 enables the aircraft to retain the existing wing and CFM Leap 1B engine from the MAX 9 with a trailing-link main landing gear as the only major change.[142] Boeing 737 MAX Vice President and General Manager Keith Leverkuhn says the design has to be frozen in 2018, for a 2020 introduction.[139]

Boeing hopes that 737-900 operators and 737 MAX 9 customers like United Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Alaska Airlines, Air Canada, Lion Air, and Chinese airlines will be interested in the new variant.[143] Boeing predicts a 5% lower trip cost and seat cost compared to the A321neo.[144] Air Lease Corporation wants it a year sooner; its CEO John Pleuger stated "It would have been better to get the first airplane in March 2019, but I don't think that's possible".[145] AerCap CEO Aengus Kelly is cautious and said the -9 and -10 "will cannibalize each other".[139]

The MAX 10 was launched on June 19, 2017, with 240 orders and commitments from more than ten customers.[146][147] United Airlines will be the largest 737 MAX 10 customer, converting 100 of their 161 orders for the MAX 9 into orders for the MAX 10.[148] Boeing ended the 2017 Paris Air Show with 361 orders and commitments, including 214 conversions, from 16 customers,[149] including 50 orders from Lion Air.[150]

The variant configuration was firmed up by February 2018,[151] and by mid-2018, the critical design review was completed. As of August 2018, assembly was underway with a first flight planned for late 2019. The semi-levered landing gear design has a telescoping oleo-pneumatic strut with a down-swinging lever to permit a 9.5 inches (24 cm) taller gear. Driven by the existing retraction system, a shrink-link mechanical linkage mechanism at the top of the leg, inspired by carrier aircraft designs, allows the gear to be drawn in and shortened while being retracted into the existing wheel well.[152][153] Entry into service is slated for July 2020.[154]

On November 22, 2019, Boeing unveiled the first MAX 10 to employees in its Renton factory, Washington, scheduled for the first flight in 2020.[155] At the time, 531 Max 10s were on order, compared to 3,142 A321neos sold, capable of carrying 244 passengers or to fly up to 4,700 nmi (8,700 km) in its heaviest A321XLR variant.[156] The Max 10 has similar capacity as A321XLR, but shorter range and much poorer field performance in smaller airports than A321XLR.[157]

Boeing Business Jet

The BBJ MAX 8 and BBJ MAX 9 are proposed business jet variants of the Boeing 737 MAX 8 and 9 with new CFM LEAP-1B engines and advanced winglets providing 13% better fuel burn than the Boeing Business Jet; the BBJ MAX 8 will have a 6,325 nmi (11,710 km) range and the BBJ MAX 9 a 6,255 nmi (11,580 km) range.[158] The BBJ MAX 7 was unveiled in October 2016, with a 7,000 nmi (12,960 km) range and 10% lower operating costs than the original BBJ while being larger.[159] The MAX BBJ 8 first flew on April 16, 2018, before delivery later the same year, and will have a range of 6,640 nmi (12,300 km) with an auxiliary fuel tank.[160]

Replacement airliner

In November 2014, Boeing talked about developing a clean sheet aircraft to replace the 737. The airplane was to have a similar fuselage but made from composite materials developed for the Dreamliner.[161] Boeing also considered a parallel development along with the 757 replacement, similar to the development of the 757 and 767 in the 1970s.[162]

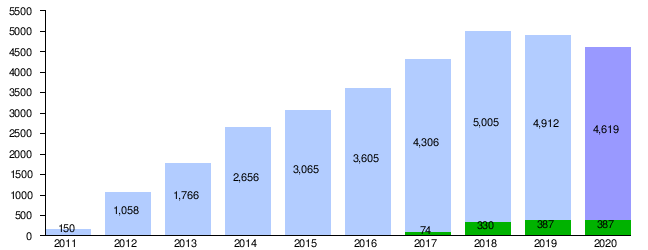

Orders and deliveries

American Airlines was the first disclosed customer. By November 17, 2011 there were 700 commitments from nine customers including Lion Air and SMBC Aviation Capital.[163][164] By December 2011, the 737 MAX had 948 commitments and firm orders from thirteen customers.[165] On September 8, 2014, Ryanair agreed to 100 firm orders with 100 options.[166] In January 2017, aircraft leasing company GECAS ordered 75.[167] By January 2019 the 737 MAX had 5,011 firm orders from 78 identified customers,[6] with the top three being Southwest Airlines with 280, flydubai with 251, and Lion Air with 251.[6] The first 737 MAX 8 was delivered to Malindo Air on May 16, 2017.[13]

Following the groundings in March 2019, Boeing suspended all deliveries of 737 MAX aircraft,[168]reduced production from 52 to 42 aircraft per month,[67] and on December 16, 2019, announced that production would be suspended from January 2020 to conserve cash and prioritize delivery of the 387 aircraft in storage once recertified.[69] At the time of the grounding, the 737 MAX had 4,636 unfilled orders[169] valued at an estimated $600 billion[170] but had a net negative 183 orders in 2019 from cancellations.[171] By May 31, 2020, orders had declined to 4,619.[6]

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total | |

| Orders | 150 | 908 | 668 | 861 | 409 | 530 | 759 | 720 | −93 | −293 | 4619 |

| Deliveries | – | – | – | – | – | – | 74 | 256 | 57 | 0 | 387 |

As of May 31, 2020[172]

Cumulative Boeing 737 MAX orders and deliveries

Orders

Deliveries

As of May 31, 2020[172]

Accidents and incidents

The global fleet of nearly 400 737 MAXs flew 500,000 flights from March 2017 to March 2019, and experienced two fatal accidents for an accident rate of four per million flights when it was grounded. The previous generations of the Boeing 737 averaged 0.2 accidents per million flights.[173]

Lion Air Flight 610

On October 29, 2018, Lion Air Flight 610, 737 MAX 8 registration PK-LQP, plunged into the Java Sea 13 minutes after takeoff from Soekarno–Hatta International Airport, Jakarta, Indonesia. The flight was a scheduled domestic flight to Depati Amir Airport, Pangkal Pinang, Indonesia. All 189 people on board died. This was the first fatal aviation accident and first hull loss of a 737 MAX. The aircraft had been delivered to Lion Air two months earlier.[174][175] People familiar with the investigation reported that during a flight piloted by a different crew on the day before the crash, the same aircraft experienced a similar malfunction but an extra pilot sitting in the cockpit jumpseat correctly diagnosed the problem and told the crew how to disable the malfunctioning Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) flight-control system.[176] Indonesia's Komite Nasional Keselamatan Transportasi released its final report into the accident on October 25, 2019,[177] attributing the crash to the MCAS pushing the aircraft into a dive due to data from a faulty angle-of-attack sensor. Following the Lion Air crash, Boeing issued an operational manual guidance, advising airlines on how to address erroneous cockpit readings.[178]

Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302

On March 10, 2019, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, 737 MAX 8 registration ET-AVJ, crashed approximately six minutes after takeoff from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,[179] on a scheduled flight to Nairobi, Kenya,[180] killing all 149 passengers and 8 crew members on board. The aircraft was four months old at the time.[181] The cause of the crash was initially unclear, though the aircraft's vertical speed after takeoff was reported to be unstable.[182] Evidence retrieved on the crash site suggests that, at the time of the crash, the aircraft was configured to dive, similar to Lion Air Flight 610.[183] On April 4, Ethiopian transport minister Dagmawit Moges stated that the crew "performed all the procedures repeatedly provided by the manufacturer but was not able to control the aircraft".[184]

The subsequent findings in the Ethiopian Airlines crash and the Lion Air crash led to the Boeing 737 MAX groundings across the world. On August 19, 2019, Forbes estimated that the 737 MAX would not resume service before 2020.[185]

Specifications

| Variant | 737 MAX 7 | 737 MAX 8 / MAX 200 | 737 MAX 9 | 737 MAX 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seating | 153 (8J + 145Y) to 172 max | 178 (12J + 166Y) to 200 max | 193 (16J + 177Y) to 220 max | 204 (16J + 188Y) to 230 max |

| Seat pitch | 28–29 in (71–74 cm) in high density, 29–30 in (74–76 cm) in economy, 36 in (91 cm) in business | |||

| Cargo capacity | 1,139 cu.ft / 32.3 m3 | 1,540 cu.ft / 43.6 m3 | 1,811 cu.ft / 51.3 m3 | 1,961 cu.ft / 55.5 m3 |

| Length | 116 ft 8 in / 35.56 m | 129 ft 6 in / 39.47 m | 138 ft 4 in / 42.16 m | 143 ft 8 in / 43.8 m |

| Wing | 117 ft 10 in / 35.92 m span, 1,370 sq ft (127 m2) area[12] | |||

| Overall height[187] | 40 ft 4 in / 12.3 m | |||

| MTOW | 177,000 lb / 80,286 kg | 181,200 lb / 82,191 kg | 194,700 lb / 88,314 kg | 197,900 lb / 89,765 kg |

| Maximum Payload | 46,040 lb / 20,882 kg | |||

| OEW[188] | 99,360 lb / 45,070 kg | |||

| Fuel capacity | 6,820 USgal / 25,816 L – 45,694 lb / 20,730 kg (no ACT)[lower-alpha 2] | |||

| Engine (× 2) | CFM International LEAP-1B, 69.4 in (176 cm) Fan diameter,[189] 26,786–29,317 lbf (119–130 kN)[12] | |||

| Cruising speed | Mach 0.79 (453 kn; 839 km/h)[190] | |||

| Range[191] | 3,850 nmi / 7,130 km | 3,550 nmi / 6,570 km[lower-alpha 3] | 3,550 nmi / 6,570 km[lower-alpha 4] | 3,300 nmi / 6,110 km[lower-alpha 4] |

| Ceiling | 41,000 ft (12,000 m)[12] | |||

| Takeoff (ISA, SL, MTOW) | 7,000 ft (2,100 m) | 8,300 ft (2,500 m) | 8,500 ft (2,600 m) | |

| Landing (SL, MLW, dry) | 5,000 ft (1,500 m) | 5,000 ft (1,500 m) | 5,500 ft (1,700 m) | |

| ICAO Type[193] | B37M | B38M | B39M | B3XM |

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Airbus A220-300 (originally developed as Bombardier CSeries)

- Airbus A320neo family

- Comac C919

- Irkut MC-21

Notes

References

- "Boeing's 737 MAX takes wing with new engines, high hopes". The Seattle Times. January 29, 2016.

- Hashim, Firdaus (May 22, 2017). "Malindo operates world's first 737 Max flight". FlightGlobal.

- Austen, Ian; Gebrekidan, Selam (March 13, 2019). "Trump Announces Ban of Boeing 737 Max Flights". The New York Times.

- "Production begins on first 737 MAX parts". Boeing Commercial Airplanes. October 13, 2014.

- Jon Hemmerdinger (May 27, 2020). "Boeing restarts 737 Max production". Flightglobal.

- "Boeing Commercial Airplanes – Orders and Deliveries – 737 Model Summary". Boeing. October 2018.

- Hemmerdinger, Jon (December 16, 2019). "Boeing to halt 737 production in January". Flight Global.

- Hamilton, Scott (January 27, 2012). "Boeing disputes 737 Max development cost report". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal.

- "About Boeing Commercial Airplanes: Prices". Boeing.

- "Boeing 737 MAX 8 Earns FAA Certification". Boeing. March 9, 2017.

- "Boeing Launches 737 New Engine Family with Commitments for 496 Airplanes from Five Airlines" (Press release). Boeing. August 30, 2011.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet No. A16WE" (PDF). FAA. March 8, 2017.

- Trimble, Stephen (May 16, 2017). "Boeing delivers first 737 Max". FlightGlobal.

- "Boeing 737 MAX - Technical Specs". Boeing. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- "Boeing Statement on 737 MAX Return to Service". MediaRoom. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- "Boeing has temporarily stopped making 737 Max airplanes". CNN. January 21, 2020.

- "Boeing firms up 737 replacement studies by appointing team". Flight International. FlightGlobal. March 3, 2006.

- Hamilton, Scott (June 24, 2010). "737 decision may slip to 2011: Credit Suisse". Flight International. FlightGlobal.

- "Airbus offers new fuel saving engine options for A320 Family". Airbus (Press release). December 1, 2010.

- Freed, Joshua (February 10, 2011). "Boeing CEO: 'new airplane' to replace 737". NBC News. Associated Press.

- "Most airlines taking cautious approach to next gen aircraft". CAPA Centre for Aviation. April 11, 2011.

- "Airbus with new order record at Paris Air Show 2011". Airbus (Press release). June 23, 2011.

- "AMR Corporation Announces Largest Aircraft Order in History With Boeing and Airbus". American Airlines (Press release). July 20, 2011.

- Clark, Nicola (July 20, 2011). "Jet Order by American is a Coup for Boeing's Rival". The New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- Russell, Edward (October 4, 2017). "United goes airframer 'agnostic' on future orders". FlightGlobal.

- Ostrower, Jon (August 30, 2011). "More details emerge on configuration of re-engined 737". Flight International. FlightGlobal. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- O'Keeffe, Niall (September 12, 2011). "Caution welcomed: Boeing's 737 Max". Flight International.

- Ostrower, Jon (February 19, 2012). "Boeing says 737 Max to meet or exceed A320neo range". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal.

- Ostrower, Jon (November 7, 2011). "Boeing completes initial review of 737 Max configuration". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal.

- Scott Hamilton (October 7, 2019). "Pontifications: Muilenburg's departure wouldn't go far enough". Leeham News.

- George, Fred (May 12, 2017). "Pilot Report: Flying the 737-8, Boeing's New Narrowbody Breadwinner". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Carvalho, Stanley (November 5, 2014). "Boeing plans to develop new airplane to replace 737 MAX by 2030". Reuters.

- Siebenmark, Jerry (August 13, 2015). "Spirit AeroSystems completes first Boeing 737 Max fuselage". Wichita Eagle.

- Gates, Dominic (December 8, 2015). "Boeing unveils the first 737 MAX and its new production line". The Seattle Times.

- DeMay, Daniel (December 8, 2015). "Photos: Boeing rolls out new 737 MAX 8 airplane". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- Trimble, Stephen (December 1, 2016). "First redesigned thrust reverser delivered for 737 Max". FlightGlobal.

- Norris, Guy (February 15, 2017). "In Pictures: First Boeing 737-9 Noses Toward Rollout". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Trimble, Stephen (April 10, 2017). "Boeing prepares for unprecedented 737 Max ramp-up". FlightGlobal.

- Gates, Dominic (February 14, 2017). "Boeing ramps up automation, innovation as it readies 737MAX". The Seattle Times.

- Gates, Dominic (April 18, 2015). "Boeing retools Renton plant with automation for 737's big ramp-up". The Seattle Times.

- Gates, Dominic (August 2, 2018). "Boeing's 737 ramp-up slows as unfinished planes pile up in Renton". The Seattle Times.

- Gates, Dominic (October 9, 2018). "Boeing finally begins to reduce its 737 delivery backlog Originally". The Seattle Times.

- "Boeing-Hosts-China-President-Xi-Jinping-Announces-Airplane-Sales-Expanded-Collaboration-with-Chinas-Aviation-Industry" (Press release). Boeing. September 23, 2015.

- "Boeing to build plant in Zhoushan". Shanghai Daily. March 14, 2017.

- Thompson, Loren. "Boeing To Build Its First Offshore Plane Factory In China As Ex-Im Bank Withers". Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- "Pictures: Boeing delivers first China-completed 737 Max". FlightGlobal. December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- Kevin Michaels (January 27, 2020). "MAX production shutdown". Aviation Week & Space Technology. p. 12.

- Gates, Dominic (March 17, 2019). "Flawed analysis, failed oversight: How Boeing, FAA certified the suspect 737 MAX flight control system". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Goold, Ian (November 8, 2017). "Boeing Forges Ahead with Flight-test Campaigns". AIN.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet No.: IM.A.120" (PDF). EASA. March 27, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- Karp, Aaron (May 10, 2017). "Boeing suspends 737 MAX flights, cites 'potential' CFM LEAP-1B issue". Air Transport World. Aviation Week Network.

- Trimble, Stephen (May 12, 2017). "Boeing resumes 737 Max 8 test flights". FlightGlobal.

- Robison, Peter; Levin, Alan (March 18, 2019). "Boeing Drops as Role in Vetting Its Own Jets Comes Under Fire". Fortune. Bloomberg. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Stieb, Matt (March 17, 2019). "Report: The Regulatory Failures of the Boeing 737 MAX". New York. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Moores, Victoria (July 18, 2017). "Norwegian performs first transatlantic 737 MAX flight". Aviation Week Network. Penton. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- Waldron, Greg (April 13, 2017). "Boeing optimistic for early 737 Max dispatch reliability". FlightGlobal.

- Mary Schlangenstein and Julie Johnsson (August 30, 2017). "Southwest Quietly Takes Delivery of Its First Boeing 737 Max". Bloomberg.

- Tinseth, Randy (May 22, 2018). "737 MAX: a year of serving the globe". Boeing.

- Benjamin Zhang (March 13, 2019). "Here's how much Boeing is estimated to make on each 737 Max 8 plane". Business Insider.

- "Boeing Stock Falls As Trump, FAA Ground Boeing 737 Max Jets In U.S. | Investor's Business Daily". Investor's Business Daily. March 14, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Polek, Gregory (January 29, 2020). "Amid Big Losses, Boeing To 'Reassess' NMA, Cut 787 Rate". Aviation International News. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- "Boeing to Recognize Charge and Increased Costs in Second Quarter Due to 737 MAX Grounding - Jul 18, 2019". MediaRoom. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Hemmerdinger, Jon (January 29, 2020). "Boeing estimates 737 Max crisis will cost $18.6 billion". Flight Global. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "Moody's cuts Boeing's debt ratings as 737 MAX problems deepen". Reuters. December 18, 2019.

- "Debris found in fuel tanks of 70% of inspected 737 Max jets". Associated Press. February 22, 2020 – via ABC News.

- "Boeing Finds Fuel-Tank Debris in Two-Thirds of 737 MAX Jets Inspected". Wall Street Journal. February 22, 2020.

- "Statement from Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg: We Own Safety - 737 MAX Software, Production and Process Update" (Press release). Boeing. April 5, 2019.

- Bruno, Michael; Dubois, Thierry (April 11, 2019). "Leap-1B Eyes Catch Up as 737 Production Slows". MRO Network.

- "Boeing Statement Regarding 737 MAX Production" (Press release). Boeing. December 16, 2019.

- "Boeing's jet deliveries slide as 737 Max grounding takes a toll". Los Angeles Times. July 9, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- Johnson, Eric M.; Hepher, Tim (December 18, 2019). "Boeing 737 MAX freeze divides suppliers into haves and have-nots". Reuters.

- McCoy, Daniel (December 31, 2019). "Moody's downgrades aerospace outlook due to 737 MAX". Wichita Business Journal. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Root, Al (January 3, 2020). "The Boeing 737 MAX Could Have a New Problem---Not Enough Engines". Barron's.

- Scott Hamilton (January 7, 2020). "Exclusive: Boeing, internally, sees production halt at least 60 days". Leeham News.

- McCoy, Daniel (January 15, 2020). "Analyst sees 737 MAX production restarting at fewer than 20 aircraft per month". Wichita Business Journals. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- "Boeing addresses new 737 MAX software issue that could keep plane grounded longer". Reuters. January 17, 2020.

- Scott Hamilton (January 29, 2020). "Boeing MAX production will restart, build slowly". Leeham News.

- Hemmerdinger, Jon (January 29, 2020). "Boeing will need a 'few years' to recapture previous 737 Max production rate plans". Flight Global. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Kilgore, Tomi. "Spirit AeroSystems to restart 737 MAX planes 'slowly,' won't hit 52/month production rate for more than 2 years". MarketWatch. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Bogaisky, Jeremy (April 6, 2020). "Boeing Moves To Completely Shut Down Airliner Production". Forbes.

- "Regulator test flight of Boeing 737 MAX delayed to May: sources". RFI. April 7, 2020.

- Shepardson, David (April 28, 2020). "Boeing 737 MAX expected to remain grounded until at least August: sources". Reuters.

- Trimble, Stephen (June 15, 2017). "737 Max cutaway and technical description". FlightGlobal.

- Norris, Guy (December 2, 2013). "Laminar Flow Boosts 737 MAX Long-Range Performance". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Trimble, Stephen (August 10, 2012). "Aviation Partners, Boeing split opinions on 737 wing-tips". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal.

- Rockwell Collins (November 15, 2012). "Rockwell Collins wins Boeing 737 MAX contract for large-format flight displays".

- "Boeing aims to minimise 737 Max changes". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal. August 31, 2011.

- "Boeing Introduces 737 MAX With Launch of New Aircraft Family" (Press release). Boeing. August 30, 2011.

- Peter Lemme (October 28, 2019). "Flawed Assumptions Pave a Path to Disaster".

- "CFM56-7B". Safran. June 1, 2015.

- Ostrower, Jon (August 31, 2011). "Boeing narrows 737 Max engine fan size options to two". FlightGlobal.

- Ostrower, Jon (November 3, 2011). "Boeing reveals 737 Max configuration details". FlightGlobal. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- "Boeing cites 600 commitments for revamped 737". Reuters. November 3, 2011.

- Ostrower, Jon (May 17, 2012). "Boeing Tweaks Engine for New 737 Max". The Wall Street Journal.

- Nicas, Jack; Kitroeff, Natalie; Gelles, David; Glanz, James (June 1, 2019). "Boeing Built Deadly Assumptions Into 737 Max, Blind to a Late Design Change". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Polek, Gregory (November 13, 2011). "Boeing Takes Minimalist Approach to 737 MAX". Aviation International News.

- Trimble, Stephen (July 23, 2013). "Boeing locks in 737 Max 8 configuration". FlightGlobal. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- Jon Ostrower (November 13, 2018). "What is the Boeing 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System". The Air Current.

- "The inside story of MCAS: How Boeing's 737 MAX system gained power and lost safeguards". The Seattle Times. June 22, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- Laris, Michael (June 19, 2019). "Changes to flawed Boeing 737 Max were kept from pilots, DeFazio says". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Hradecky, Simon (January 14, 2019). "Crash: Lion B38M near Jakarta on Oct 29th 2018, aircraft lost height and crashed into Java Sea, wrong AoA data". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- Andy Pasztor; Andrew Tangel; Alison Sider (May 6, 2019). "Boeing Knew of Problem for a Year". Wall Street Journal. p. A1.

- Ostrower, Jon (August 30, 2011). "Boeing designates 737 MAX family". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- "Boeing Delivers First 737 MAX 9" (Press release). Boeing. March 21, 2018.

- Mcgough, Michael (March 16, 2018). "New Boeing 737 Max hits the skies. How its performance could impact flights to Hawaii". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- Calder, Simon (March 11, 2019). "Which routes does the Boeing 737 MAX fly, and what are my options if I'm booked on one?". The Independent. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

For British travellers, the most significant order is from Ryanair, which has 135 of a special version of the MAX 8 – the MAX 200, holding 197 passengers, eight more than the number of seats on its existing Boeing 737s. The first aircraft are due to enter service from Stansted on May 14,, on flights to Tenerife and Thessaloniki, with links to Athens, Corfu, Faro, Lisbon, Madrid, Malaga, Malta, Rhodes, Venice and many other locations.

- Trimble, Stephen (October 4, 2017). "Boeing starts building first 737 Max 7". FlightGlobal.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max (February 7, 2018). "Detailed design starts on 737 Max 10". FlightGlobal.

- "Farnborough: Boeing's Execution on 737 MAX Sparkles as MAX 7.5 and MAX 10X Loom". Airways Magazine. July 10, 2016.

- "Boeing confirms 737 Max 7 redesign". FlightGlobal. July 11, 2016.

- "Boeing Upscales 737-700". Aviation International News. July 12, 2016.

- Norris, Guy (March 16, 2018). "Boeing Begins 737-7 Flight Test Program". Aviation Week Network.

- "Boeing plans performance upgrade for 737 Max after 2021". FlightGlobal. October 31, 2016.

- Trimble, Stephen (November 23, 2017). "Boeing starts assembling first Max 7". FlightGlobal.

- Gates, Dominic (February 5, 2018). "Boeing debuts MAX 7 jet, smallest and slowest-selling of its 737 MAX family". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "Boeing 737 Max 7 narrowbody jetliner makes maiden flight". Reuters. March 16, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Trimble, Stephen (March 16, 2018). "Boeing launches 737 Max 7 into flight testing". FlightGlobal.

- Yeo, Ghim-Lay (January 2, 2018). "Southwest converts options for 40 more 737 Max 8s". FlightGlobal.

- "Canada's WestJet defers maiden B737 MAX 7 to 2021". ch-aviation. August 1, 2018.

- "Boeing Completes 737 MAX 8 Firm Configuration". Boeing, July 23, 2013.

- "737 MAX 8 performs first international flight". AeroLatin News. May 3, 2016.

- "End of Line B737-800 Values Show Fatigue". Aircraft Value News. September 17, 2018.

- "Boeing Launches 737 MAX 200 with Ryanair" (Press release). Boeing. September 8, 2014.

- Gates, Dominic (September 8, 2014). "Ryanair makes big order for 737 MAX jets that can carry 200". The Seattle Times.

- "Update 5-Ryanair buys 100 Boeing 737 MAX jets, sees fare price war". Reuters. September 8, 2014.

- "Ryanair, Boeing Finalize Max 200 Deal". Aviation International News. December 1, 2014.

- David Kaminski-Morrow (July 15, 2019). "New name for Ryanair 737 Max is not actually new". Flightglobal.

- Noëth, Bart (November 19, 2018). "Ryanair's first Boeing 737 MAX 200 aircraft has rolled out of Boeing's final assembly line". Aviation24.be.

- "First High-Capacity Boeing 737-8 Enters Flight Test Jan 23, 2019 Guy Norris". Aviation Week Network.

- Clark, Oliver (February 14, 2019). "Ryanair Max to make debut at Stansted". FlightGlobal.

- Max Kingsley Jones (May 24, 2019). "Ryanair ready to place more 737 Max orders: O'Leary". Flightglobal.

- Ostrower, Jon (November 26, 2019). "Boeing 737 Max re-certificaton likely to slide into 2020, Ryanair model faces new design issue". The Air Current.

- "Boeing showing 737-8ERX concept in response to A321LR". Leeham News. March 12, 2015.

- "Boeing's 737 MAX 9 takes off on first flight". The Seattle Times. April 13, 2017.

- "Boeing completes 737 Max 9 maiden flight". FlightGlobal. April 13, 2017.

- "Civil Aviation Programs To Watch". Aviation Week & Space Technology. June 9, 2017.

- Trimble, Stephen (February 16, 2018). "Boeing 737 Max 9 receives certification". FlightGlobal.

- Aircraft Value News (November 12, 2018). "B737-9 EASA Certification Does Nothing for Values".

- Flottau, Jens (March 10, 2017). "Customers Press Boeing To Launch New Midsize Widebody Aircraft Soon". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Trimble, Stephen (July 4, 2016). "Farnborough: Proposed stretch of 737 Max 9 possible, but challenging". FlightGlobal.

- Norris, Guy (September 30, 2016). "Simpler 737-10X, New Midsize Airplane Both 'Doable'". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Norris, Guy (January 10, 2017). "Boeing Defines Final 737 MAX Stretch Offering". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Ostrower, Jon (January 12, 2017). "Boeing chases airlines for stretch 737". CNN.

- Tinseth, Randy (March 6, 2017). "MAX 10X". Boeing.

- Johnsson, Julie (March 7, 2017). "Boeing's Longest 737 Max Can't Debut Too Soon for One Buyer". Bloomberg.

- "Boeing Launches Larger Capacity 737 MAX 10 at 2017 Paris Air Show" (Press release). Boeing. June 19, 2017.

- Trimble, Stephen (June 19, 2017). "Boeing launches 737 Max 10". Flightglobal.

- Dron, Alan (June 20, 2017). "United converts 100 MAX to -10 variant; CALC includes -10s in order". Aviation Week Network.

- "Propelled by MAX 10, Boeing thumps Airbus at Paris Air Show". Leeham. June 22, 2017.

- "Boeing, Lion Air Group Announce Commitment for 50 737 MAX 10s" (Press release). Boeing. June 19, 2017.

- "Boeing 737 MAX 10 Reaches Firm Configuration" (Press release). Boeing. February 6, 2018.

- Norris, Guy (August 30, 2018). "Boeing Unveils 737-10 Extended Main Landing Gear Design Details". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Norris, Guy (February 9, 2018). "Boeing Completes Configuration For Final 737 MAX Derivative". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- "Airport Compatibility Brochure Boeing 737 MAX 10" (PDF). Boeing. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- "Boeing 737 MAX 10 Makes its Debut" (Press release). Boeing. November 22, 2019.

- Jon Hemmerdinger (November 23, 2019). "Muted Boeing unveils 737 Max 10". Flightglobal.

- "Why the A321XLR makes sense for Alaska Airlines". Leeham News and Analysis. February 23, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- "Boeing Business Jets to Offer the BBJ MAX" (Press release). Boeing. October 29, 2012.

- "Boeing Business Jets Unveils BBJ MAX 7" (Press release). Boeing. October 31, 2016.

- "Milestone paves the way for delivery of the newest version of the best-selling business jetliner" (Press release). Boeing. April 16, 2018.

- "Boeing plans to develop new airplane to replace 737 MAX by 2030". Reuters. November 5, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- Guy Norris and Jens Flottau (December 12, 2014). "Boeing Revisits Past In Hunt For 737/757 Successors". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- "Lion Air commits to up to 380 Boeing 737s". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal. November 17, 2011.

- "ACG Becomes third identified 737 Max customer". November 17, 2011.

- "737 Max commitments top 948". Air Transport Intelligence News. FlightGlobal. December 13, 2011.

- "Ryanair places $22bn order with Boeing, buys up to 200 new aircraft". Independent.ie. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Boeing, GECAS Announce Order for 75 737 MAXs" (Press release). Boeing. January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- "Lion Air Said to Plan Airbus Order Switch After Boeing 737 Crash". Bloomberg. March 12, 2019.

- Sutherland, Brooke (March 19, 2019). "China's Boeing Threat Has More Bite Than Bark". Bloomberg News.

- Genga, Bella; Odeh, Layan (March 13, 2019). "Boeing's 737 Max Problems Put $600 Billion in Orders at Risk". Bloomberg News.

- Lee, Liz; Freed, Jamie (January 15, 2020). "Malaysia Airlines suspends Boeing 737 MAX deliveries due to jet's grounding". Reuters.

- "Boeing 737: Orders and Deliveries (updated monthly)". The Boeing Company. May 31, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- "The Boeing 737 Max is now the deadliest mainstream jetliner". finance.yahoo.com. March 11, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- "Lion Air: How could a brand new plane crash?". BBC News Online. October 29, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- Indah Mutiara Kami (October 29, 2018). "Breaking News: Basarnas Pastikan Pesawat Lion Air JT 610 Jatuh". Detik.com. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- Alan Levin; Harry Suhartono (March 20, 2019). "Pilot Who Hitched a Ride Saved Lion Air 737 Day Before Deadly Crash". Bloomberg. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Aircraft Accident Investigation Report. PT. Lion Airlines Boeing 737 (MAX); PK-LQP Tanjung Karawang, West Java, Republic of Indonesia 29 October 2018" (PDF). Komite Nasional Keselamatan Transportasi. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- "Boeing issues operational manual guidance to airlines following Lion Air crash". CNN. November 7, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "Ethiopian Airlines: 'No survivors' on crashed Boeing 737". BBC News Online. March 10, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "Official pressrelease". ethiopianairlines.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Hilsz-Lothian, Aaron (March 10, 2019). "Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 737 MAX involved in fatal crash". SamChui.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "157 feared dead in Ethiopian plane crash". The Guardian. March 10, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Lazo, Luz; Schemm, Paul; Aratani, Lori. "Investigators find 2nd piece of key evidence in crash of Boeing 737 Max 8 in Ethiopia". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- "Ethiopian Airlines crew 'followed rules, unable to control jet'". Al Jazeera. April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Asquith, James (August 19, 2019). "When Will the Boeing 737 MAX Fly Again? Not This Year". Forbes. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- "737 MAX Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF) (Rev. E ed.). Boeing. July 2019.

- "Boeing 737 MAX by design". Boeing.

- "737 MAX Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF) (Rev. A ed.). Boeing. August 2017.

- "LEAP Brochure" (PDF). CFM International. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015.

- "737MAX and the MD-12". Aviation Week. December 9, 2013.

- "737 MAX". Boeing. Technical Specs.

- "Boeing Revises "Obsolete" Performance Assumptions". FlightGlobal. August 3, 2015.

- "DOC 8643 – Aircraft Type Designators". ICAO.

Further reading

- Wise, Jeff (March 11, 2019). "Where did Boeing go wrong?". Slate.

- "Countdown to Launch: The Boeing 737 MAX Timeline". Airways. January 27, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Official website

- Smith, Paul (May 12, 2017). "Flight test: Boeing's 737 Max – the same but different". FlightGlobal.