Blood Bath

Blood Bath is a 1966 American horror film directed by Jack Hill and Stephanie Rothman and starring William Campbell, Linda Saunders, Marissa Mathes, and Sid Haig. The film concerns a delusional painter in Venice Beach, California who believes himself to be the reincarnation of a vampire. He begins to kidnap local women for his art pieces, and comes to believe that he has found his reincarnated mistress in the person of an avant-garde ballerina.

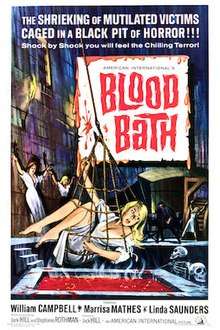

| Blood Bath | |

|---|---|

US theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Hill Stephanie Rothman |

| Produced by | Jack Hill |

| Written by | Jack Hill Stephanie Rothman |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Ronald Stein |

| Cinematography | Alfred Taylor |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 69 minutes |

| Language | English |

Blood Bath had a complex and troubled production history, marked by various cuts and reshoots. In 1963 Roger Corman had co-produced a Yugoslavia-made spy thriller called Operation: Titian, but the film was deemed unreleasable. Corman purchased the rights to another film and assigned writer-director Jack Hill to write a new script. This time, it was a horror film that incorporated the previous footage from Operation: Titian. Hill wrote and directed numerous horror sequences that were edited into the film, and it was re-titled Portrait in Terror. Still unsatisfied with the completed product, Corman hired Stephanie Rothman to film additional sequences that were also added. This cobbled-together feature was given a brief theatrical release by American International Pictures under the title Blood Bath, with screenplay and directorial credit jointly shared by Hill and Rothman.[1] An additional version of the film was made for television and re-titled Track of the Vampire.

Plot

In Venice Beach, Los Angeles, student Daisy leaves a club alone after having an argument with her beatnik boyfriend Max. Walking through the deserted streets, she stops to admire some gruesome paintings in a gallery window painted by artist Antonio Sordi, who coincidentally also comes by to look in on his "lost children." After a friendly conversation, Sordi convinces the young woman to pose nude for him that night. At his bell-tower studio, Sordi is possessed by the spirit of a long-dead ancestor and suddenly transforms into a vampiric monster who hacks the screaming Daisy to death with a cleaver. Afterwards, he lowers her mutilated corpse into a vat of boiling wax.

Sordi, in his vampire form, stalks Venice in search of victims; he is able to do so freely at all hours. In the middle of the day, he chases a young woman into the surf at a beach and drowns her. At night, he kills a prostitute in a car while pedestrians stroll by, all of them assuming the pair are lovers sharing an intimate moment. Another victim is approached at a party, chased into a swimming pool, and drowned there after the other guests have moved into the house. The murdered women are carried back to Sordi's studio and painted by the artist, their bodies then covered in wax.

Max wants to make up with Daisy but cannot find her anywhere. Learning that she has posed for Sordi and become the subject of the latest in the artist's series of "Dead Red Nudes," he visits her sister Donna to ask her forgiveness. Donna tells Max she hasn't seen Daisy for days, and is concerned about the recent rash of disappearances. She reads Max the legend of Sordi's 15th-century ancestor Erno, a painter condemned to be burned at the stake for capturing his subjects' souls on canvas. Unable to convince Max that Antonio Sordi might also be a vampire, she confronts the artist at his studio and asks him if he has seen Daisy. He angrily brushes her off. That night, he later follows her through the streets and murders her as she tries to escape from him on a carousel.

The "human" Sordi is in love with Dorian, an avant-garde ballerina and Daisy's former roommate. At first he tries to protect her from his vampiric tendencies, warning her his studio is a cheerless place and at one point breaking a date with her to spend time gaining control of his feelings for her. When she turns up at the studio unannounced, he believes she is the reincarnation of Erno Sordi’s long-dead mistress Melizza, a witch who had denounced him to the ecclesiastical courts in order to protect herself from prosecution, and traps her in a net. He is about to slash her throat with a razor when Max and his beatnik friends finally realize Sordi is a murderer and successfully free her from the tower. Melizza, seen in a painting that Sordi keeps concealed behind a curtain, brings three of Sordi's victims back to life and they dispatch him by forcing him into the boiling wax.

Cast

- William Campbell as Antonio Sordi

- Marissa Mathes as Daisy Allen

- Lori Saunders as Dorian / Melizza

- Sandra Knight as Donna Allen

- Karl Schanzer as Max

- Sid Haig as Abdul

- Biff Elliot as Cafe Manager

- Jonathan Haze as Beatnik

- Fred Thompson as Beatnik

- David Ackles as Carousel Operator

Production

Operation: Titian

In 1963, while on vacation in Europe, Roger Corman made a deal to distribute an unproduced Yugoslavian espionage thriller titled Operacija Ticijan/Operation: Titian, shot in Yugoslavia.[2] Corman bought the rights to the film for $20,000 and insisted on control over the production to ensure it could be adequately “Americanized”. To this end, Corman provided two cast members, William Campbell and Patrick Magee, who had appeared together in Corman’s The Young Racers and Francis Ford Coppola’s Corman-produced Dementia 13. In addition, Coppola was installed as the production’s script supervisor.[3] The completed film was deemed unreleasable by Corman, although a redubbed, slightly re-edited version was eventually released directly to television under the title Portrait in Terror.[4]

Reconception as Blood Bath

In 1964, Corman asked director Jack Hill to salvage the film. Hill wrote and filmed additional sequences in Venice, California, in order to match the original movie’s European look, and turned the former spy thriller into a horror movie about a crazed madman who kills his models and makes sculptures out of their dead bodies. Campbell was available for the reshoots and insisted on a sizeable paycheck to appear in the film, reportedly angering Corman, who nonetheless agreed to the actor’s demands. Hill added all of the beatnik-related scenes shot with Sid Haig and Jonathan Haze, and was responsible for what many fans believe is the single most effective sequence in the film, the hatchet murder of Melissa Mathes. Magee’s role was more or less retained intact in this version. However, Hill’s version of the film, retitled Blood Bath, has never been released, as Corman once again was unhappy with the results.[5]

In 1966, Corman made another attempt to create a workable film. He hired another director, Stephanie Rothman, to change the story as she saw fit. While retaining much of Hill’s footage, she changed the plot from a story about a deranged, murderous artist to a story about a deranged, murderous artist who is also a vampire.[6] Because Campbell refused to participate in yet another reshoot, Rothman was forced to use a completely different actor for the new murder scenes. This meant Rothman now had to provide the Campbell character with the ability to magically transform his physical shape whenever he turned into a vampire, in order to explain why the vampire-killer looked nothing like Campbell. Other complications including bringing Sid Haig back for re-shoots; at the time of shooting with Hill, he did not have a beard, but had grown one for the subsequent project he was working on. This explains the continuity errors concerning his facial hair in the film.[7]

In spite of the inconsistencies brought on by Rothman's additional shoots, this was this version of the film that most pleased Corman, and it was subsequently released to theatres by American International Pictures, retaining Hill's Blood Bath title. Both Hill and Rothman were credited as co-directors. Hill later claimed that Rothman's changes "totally ruined" the film.[8]

A fifth version of the film exists, entitled Track of the Vampire.[9] Because Rothman's Blood Bath ran 69 minutes, which was deemed too short for television showings, additional footage was added, including a six-minute sequence showing Linda Saunders dancing non-stop on the beach. This version of the film was shown often on late-night television.[10]

Commenting on the film's convoluted history, Hill stated:

Blood Bath was my script. It was my title. After I left, Roger decided that he didn't think that the Yugoslavian footage matched the footage that we had shot in Venice. You see, both Portrait of Terror and Blood Bath came out of this same footage. Roger got the idea that he could sell the original movie to television and have Stephanie Rothman pad out what I shot with further scenes to make another full-length movie—and wind up with two movies instead of one. This is the kind of nutso stuff that went through there. So Stephanie wrote new scenes and shot them, and turned it into a vampire movie.[11]

Release

Blood Bath debuted in cinemas in March 1966 through American International Pictures, and was screened as a double feature with Queen of Blood (1966),[12][13] written and directed by Curtis Harrington and co-produced by Rothman.

Critical response

Michael Weldon, in his Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, called Blood Bath “a confusing but interesting horror film with an even more confusing history.[10] Phil Hardy’s The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror noted, “Cheap and crude, with echoes of a dozen movies ranging from Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) to A Bucket of Blood (1959), this film isn’t unenjoyable."[14] Cavett Binion of AllMovie wrote, "As one might imagine, this is pretty difficult to follow, but there are some good performances — particularly from William Campbell as the haunted shutterbug — and some fairly suspenseful scenes."[15]

In 1991, Video Watchdog magazine devoted lengthy articles in three separate issues fully detailing the production history of the film. These articles included interviews with Hill and Campbell, the latter of whom expressed shock when he was told that the film he had shot so long ago in Yugoslavia had been turned into five individual movies.[2]

Clayton Dillard of Slant Magazine awarded the film four out of five stars, writing: "Purely as a film, Blood Bath expectedly turns out to be a mash-up of styles and tones, with surrealist flourishes (a tracking shot focused on Sordi in the wide-open California desert) juxtaposing routine scenes of women being lured to the villain’s lair. Everything within it is odd, from rampant continuity errors, to unintelligible footage of shadowy figures from the preceding films interspersed throughout."[16]

Home media

The film was released on DVD in 2011 through Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's "Limited Edition Collection," which are made-on-demand discs. In May 2016, the film was released on Blu-ray in a limited edition two-disc set by Arrow Films. It features all four versions of the film restored from the original negatives: the original Operation: Titian; Jack Hill's original Blood Bath; Blood Bath featuring Stephanie Rothman's re-shoots; and Track of the Vampire.[9]

See also

- Vampire film

References

- "Blood Bath". Arrow Films. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- Lucas, Tim (2016). The Trouble with Titian - Revisited (Blu-ray - Visual essay). Arrow Films.

- Dixon 2007, p. 89.

- Horwath, Elsaesser & King 2005, p. 127.

- Weldon 1983, p. 63.

- Creed 1993, p. 62.

- "Bathing in Blood with Sid Haig" (Interview). Interviewed by Sid Haig. Arrow Films. 2016.

- Jack Hill on Blood Bath at Trailers From Hell

- Dillard, Clayton (June 2, 2016). "Blood Bath - Blu-ray Review". Slant.

- Weldon 1983, p. 436.

- Dixon 2007, pp. 89–90.

- "Atlanta's Finest Drive-In Theatres". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. March 16, 1966. p. 46} – via Newspapers.com.

- "Films with a beat are scheduled this week at city area theaters". Johnson City Press. Johnson City, Tennessee. December 11, 1966. p. 41 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hardy, Phil (editor). The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror, Aurum Press, 1984. Reprinted as The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Horror, Overlook Press, 1995, ISBN 0-87951-518-X

- Binion, Cavett. "Track of the Vampire". AllMovie. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- Dillard, Clayton (June 2, 2016). "Blood Bath". Slant Magazine. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

Sources

- Creed, Barbara (1993). The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (1 ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05259-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (2007). Film Talk: Directors at Work. Rutgers, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-813-54147-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horwath, Alexander; Elsaesser, Thomas; King, Noel, eds. (2005). The Last Great American Picture Show: New Hollywood Cinema in the 1970s. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9-053-56631-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lucas, Tim (1990). "The Trouble with Titan Part Two". Video Watchdog. No. 5. p. 23-31.

- Lucas, Tim (1991). "The Trouble with Titan Part Three". Video Watchdog. No. 7. p. 19-28.

- Weldon, Michael (1983). The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-34345-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Blood Bath on IMDb

- Allmovie: Blood Bath/Track of the Vampire entry

- Jack Hill on Blood Bath at Trailers From Hell

- Article in Video Watchdog Part 2

- Article in Video Watchdog Part 3