Birgeria

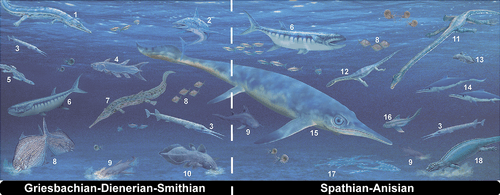

Birgeria is a genus of carnivorous marine ray-finned fish from the Triassic period.[3] It is extinct. Birgeria had a global distribution. Fossils were found in Madagascar, Spitsbergen, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Slovenia, China, Russia, Canada and Nevada, United States. The oldest fossils are from Griesbachian aged beds of the Wordie Creek Formation of East Greenland.

| Birgeria | |

|---|---|

| Fossil of Birgeria acuminata, Civic Museum of Natural Science, Bergamo, Italy.[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Infraphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | †Birgeriformes |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Birgeria Stensiö, 1919 |

| Type species | |

| †Birgeria mougeoti (Agassiz, 1844) | |

| Other species | |

| |

The type species was first described as Saurichthys mougeoti. Following a reinvestigation, Erik Stensiö concluded that this species cannot be ascribed to Saurichthys. He thus erected a new genus, which he named after his colleague Birger Sjöström, who had joined him on an expedition to the Arctic island of Spitsbergen (Svalbard) in 1915.[4]

Appearance

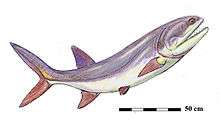

The scale cover of Birgeria is reduced. Most of the body is devoid of scales. Scales are only developed on the upper lobe of the caudal fin and the hind portion of the caudal peduncle. The scales are small, rhombic and lack a ganoine layer.

The tail fin is large and deeply forked. The dorsal and anal fins are situated at the same level in the back of the body. The fin rays are segmented.

The eyes were located in the front of the skull. The gape is large. The "parietals" (postparietals) are small and medially separated by the elongate "frontals" (parietals). The postrostral is large. The (rostro-)premaxilla is unpaired. The maxilla is cleaver-shaped with a large postorbital blade. Two to three rows of conical teeth are present. The teeth normally show cutting edges. The preopercle is boomerang-shaped. The bones of the gill cover are small, often weakly ossified or not ossified at all.

Ecology

Birgeria was an apex predator among Triassic ray-finned fish, together with Saurichthys. Most species of Birgeria grew over 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length, some even up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) or possibly more. Some of the largest species are Birgeria aldingeri (Spitsbergen) and Birgeria americana (USA).[5]

A specimen of Birgeria nielseni from Madagascar was described as supposedly carrying embryos whose bodies are covered with rhombic scales. However, this interpretation was later dismissed.[6] It is more likely that these "embryos" were actually preyed ray-fins, which would indicate that the diet of Birgeria included small actinopterygians. Unlike Saurichthys, Birgeria was probably not viviparous. This view is supported by the fact that fossils with copulatory organs are yet unknown.

Based on its anatomical features, Birgeria is interpreted as a pelagic, swift swimmer. Fossils are sparse, which supports the view that it lived offshore.

Systematics

Birgeria is the only genus of the family Birgeriidae (monotypy). Psilichthys, Ohmdenia and Brazilichthys are not closely related to Birgeria and therefore excluded from Birgeriidae.[7][8]

A few species, such as Birgeria? costata or Birgeria? annulata, are only known from fragmentary material. Their affinity with Birgeria is uncertain. With about eight valid species, Birgeria was much less speciose than Saurichthys.

References

- Stefani et al. (1992): Palaeoenvironment of extraordinary fossil biotas from the Upper Triassic of Italy. Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano 132:309-335. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289957463_Palaeoenvironment_of_extraordinary_fossil_biotas_from_the_Upper_Triassic_of_Italy

- Scheyer et al. (2014): Early Triassic Marine Biotic Recovery: The Predators' Perspective. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088987

- Romano, C. & Brinkmann, W. (2009). "Reappraisal of the lower actinopterygian Birgeria stensioei ALDINGER, 1931 (Osteichthyes; Birgeriidae) from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio (Switzerland) and Besano (Italy)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 252: 17–31. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2009/0252-0017.

- Stensiö, E. 1919, Einige Bemerkungen über die systematische Stellung von Saurichthys mougeoti Agassiz: Senckenbergiana 1:177–181.

- Romano et al. (2017): Marine Early Triassic Actinopterygii from Elko County (Nevada, USA): implications for the Smithian equatorial vertebrate eclipse. Journal of Paleontology 91:1025-1046 https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2017.36

- Bürgin, T. (1990): Reproduction in Middle Triassic actinopterygians; complex fin structures and evidence of viviparity in fossil fishes. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 100:379–391. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1990.tb01866.x

- Rodrigo T. Figueroa; Matt Friedman; Valéria Gallo (2019). Cranial anatomy of the predatory actinopterygian Brazilichthys macrognathus from the Permian (Cisuralian) Pedra de Fogo Formation, Parnaíba Basin, Brazil. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39: e1639722. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2019.1639722

- M. Friedmann. 2012. Parallel evolutionary trajectories underlie the origin of the giant suspension-feeding whales and bony fish. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 279: 944-951

Further reading

- Fossils (Smithsonian Handbooks) by David Ward (Page 211)