Biosimilar

A biosimilar is a biologic medical product (also known as biologic) highly similar to another already approved biological medicine (the 'reference medicine'). Biosimilars are approved according to the same standards of pharmaceutical quality, safety and efficacy that apply to all biological medicines.[1] Biosimilars are officially approved versions of original "innovator" products and can be manufactured when the original product's patent expires.[2] Reference to the innovator product is an integral component of the approval.

Unlike with generic drugs of the more common small-molecule type, biologics generally exhibit high molecular complexity and may be quite sensitive to changes in manufacturing processes. Despite that heterogeneity, all biopharmaceuticals, including biosimilars, must maintain consistent quality and clinical performance throughout their lifecycle.[3] A biosimilar is not regarded as a generic of a biological medicine. This is mostly because the natural variability and more complex manufacturing of biological medicines do not allow an exact replication of the molecular micro-heterogeneity.[1] Drug-related authorities such as the EU's European Medicines Agency (EMA), the US's Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Health Products and Food Branch of Health Canada hold their own guidance on requirements for demonstration of the similar nature of two biological products in terms of safety and efficacy. According to them, analytical studies demonstrate that the biological product is highly similar to the reference product, despite minor differences in clinically inactive components, animal studies (including the assessment of toxicity), and a clinical study or studies (including the assessment of immunogenicity and pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics). They are sufficient to demonstrate safety, purity, and potency in one or more appropriate conditions of use for which the reference product is licensed and is intended to be used and for which licensure is sought for the biological product.

The World Health Organization (WHO) published its "Guidelines for the evaluation of similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs)" in 2009. The purpose of this guideline is to provide an international norm for evaluating biosimilars with a high degree of similarity with an already licensed, reference biotherapeutic medicine.[4][5][6][7]

The European Union was the first region in the world to develop a legal, regulatory, and scientific framework for approving biosimilar medicines. The EMA has granted a marketing authorization for more than 50 biosimilars since 2006 (first approved biosimilar Somatropin(Growth hormone)). The first biosimilar of a monoclonal antibody to be approved worldwide was a biosimilar of infliximab in the EU in 2013.[1] On March 6, 2015, the FDA approved the United States's first biosimilar product, the biosimilar of filgrastim called filgrastim-sndz (trade name Zarxio) by Sandoz.

Approval processes

Approval of medicines in the EU relies on a solid legal framework, which in 2004, introduced a dedicated route for the approval of biosimilars. The EU has pioneered the regulation of biosimilars since the approval of the first one (the growth hormone somatropin) in 2006. Since then, the EU has approved the highest number of biosimilars worldwide, and consequently has the most extensive experience of their use and safety. All medicines produced using biotechnology and those for specific indications (e.g. for cancer, neurodegeneration and auto-immune diseases) must be approved in the EU through the EMA (via the so-called 'centralised procedure'). Nearly all biosimilars approved for use in the EU have been approved centrally, as they use biotechnology for their production. Some biosimilars may be approved at national level, such as some low-molecular weight heparins derived from porcine intestinal mucosa. When a company applies for marketing authorization at EMA, data are evaluated by EMA's scientific committees on human medicines and on safety (the CHMP and PRAC), as well as by EU experts on biological medicines (Biologics Working Party) and specialists in biosimilars (Biosimilar Working Party). The review by EMA results in a scientific opinion, which is then sent to the European Commission, which ultimately grants an EU-wide marketing authorization.[8]

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) held that new legislation was required to enable them to approve biosimilars to those biologics originally approved through the PHS Act pathway.[9] Additional Congressional hearings have been held.[10] On March 17, 2009, the Pathway for Biosimilars Act was introduced in the House.[2] See the Library of Congress website and search H.R. 1548 in 111th Congress Session. Since 2004 the FDA has held a series of public meetings on biosimilars.[11][12]

The FDA gained the authority to approve biosimilars (including interchangeables that are substitutable with their reference product) as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act signed into law by President Obama on March 23, 2010.

The FDA has previously approved biologic products using comparability, for example, Omnitrope in May 2006, but this like Enoxaparin was also to a reference product, Genotropin, originally approved as a biologic drug under the FD&C Act.[13]

On March 6, 2015, Zarxio obtained the first approval of FDA.[14] Sandoz's Zarxio is biosimilar to Amgen's Neupogen (filgrastim), which was originally licensed in 1991. This is the first product to be passed under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act), which was passed as part of the Affordable Healthcare Act. But Zarxio was approved as a biosimilar, not as an interchangeable product, the FDA notes. And under the BPCI Act, only a biologic that has been approved as an "interchangeable" may be substituted for the reference product without the intervention of the health care provider who prescribed the reference product. The FDA said its approval of Zarxio is based on review of evidence that included structural and functional characterization, animal study data, human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data, clinical immunogenicity data and other clinical safety and effectiveness data that demonstrates Zarxio is biosimilar to Neupogen.

In March 2020, most protein products that were approved as drug products (including every insulin currently on the market as of December 2019) are scheduled to open up to biosimilar and interchangeable competition in the United States.[15] However, "chemically synthesized polypeptides" are excluded from this transition, which means that a product that falls within this category won't be able to come to market as a biosimilar or interchangeable product, but will have to come to the market under a different pathway.[15]

Background

Cloning of human genetic material and development of in vitro biological production systems has allowed the production of virtually any recombinant DNA based biological substance for eventual development of a drug. Monoclonal antibody technology combined with recombinant DNA technology has paved the way for tailor-made and targeted medicines. Gene- and cell-based therapies are emerging as new approaches.

Recombinant therapeutic proteins are of a complex nature (composed of a long chain of amino acids, modified amino acids, derivatized by sugar moieties, folded by complex mechanisms). These proteins are made in living cells (bacteria, yeast, animal or human cell lines). The ultimate characteristics of a drug containing a recombinant therapeutic protein are to a large part determined by the process through which they are produced: choice of the cell type, development of the genetically modified cell for production, production process, purification process, formulation of the therapeutic protein into a drug.

After the expiry of the patent of approved recombinant drugs (e.g., insulin, human growth hormone, interferons, erythropoietin, monoclonal antibodies and more) any other biotech company can develop and market these biologics (thus called biosimilars). Every biological (or biopharmaceutical products) displays a certain degree of variability, even between different batches of the same product, which is due to the inherent variability of the biological expression system and the manufacturing process.[16] Any kind of reference product has undergone numerous changes in its manufacturing processes, and such changes in the manufacturing process (ranging from a change in the supplier of cell culture media to new purification methods or new manufacturing sites) was substantiated with appropriate data and was approved by the EMA. In contrast, it is mandatory for biosimilars to take a both non-clinical and clinical test that the most sensitive clinical models are asked to show to enable detection of differences between the two products in terms of human pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD), efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity.

The current concept of development of biosimilar mAbs follows the principle that an extensive state of the art physicochemical, analytical and functional comparison of the molecules is complemented by comparative non-clinical and clinical data that establish equivalent efficacy and safety in a clinical "model" indication that is most sensitive to detect any minor differences (if these exist) between biosimilar and its reference mAb also at the clinical level.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recognized this fact, which has resulted in the establishment of the term "biosimilar" in recognition that, whilst biosimilar products are similar to the original product, they are not exactly the same.[17] Every biological displays a certain degree of variability. However, provided that structure and function(s), pharmacokinetic profiles and pharmacodynamic effect(s) and/or efficacy can be shown to be comparable for the biosimilar and the reference product, those adverse drug reactions which are related to exaggerated pharmacological effects can also be expected at similar frequencies.

Originally the complexity of biological molecules led to requests for substantial efficacy and safety data for a biosimilar approval. This has been progressively replaced with a greater dependence on assays, from quality through to clinical, that show assay sensitivity sufficient to detect any significant difference in dose.[18] However, the safe application of biologics depends on an informed and appropriate use by healthcare professionals and patients. Introduction of biosimilars also requires a specifically designed pharmacovigilance plan. It is difficult and costly to recreate biologics because the complex proteins are derived from living organisms that are genetically modified. In contrast, small molecule drugs made up of a chemically based compound can be easily replicated and are considerably less expensive to reproduce. In order to be released to the public, biosimilars must be shown to be as close to identical to the parent innovator biologic product based on data compiled through clinical, animal, analytical studies and conformational status.[19][20]

Generally, once a drug is released in the market by the FDA, it has to be re-evaluated for its safety and efficacy once every six months for the first and second years. Afterward, re-evaluations are conducted yearly, and the result of the assessment should be reported to authorities such as FDA. Biosimilars are required to undergo pharmacovigilance (PVG) regulations as its reference product. Thus biosimilars approved by the EMA (European Medicines Agency) are required to submit a risk management plan (RMP) along with the marketing application and have to provide regular safety update reports after the product is in the market. The RMP includes the safety profile of the drug and proposes the prospective pharmacovigilance studies.

Several PK studies, such as studies conducted by Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), have been conducted under various ranges of conditions; Antibodies from an originator's product versus antibodies from an biosimilar; combination therapy and monotherapy; various diseases, etc. on the purpose to verify comparability in pharmacokinetics of the biosimilar with the reference medicinal product in a sufficiently sensitive and homogeneous population. Importantly, provided that structure and function(s), pharmacokinetic profiles and pharmacodynamic effect(s) and/or efficacy can be shown to be comparable for the biosimilar and the reference product, those adverse drug reactions which are related to exaggerated pharmacological effects can also be expected at similar frequencies.

European Union approvals of biosimilars

The European Union has the largest number of approved biosimilar medicines up to date. The EMA's scientific committees evaluate the majority of marketing authorization applications for biosimilar medicines before they can be approved and marketed in the EU. The EMA evaluates biosimilars according to the same standards of pharmaceutical quality, safety and efficacy that apply to all biological medicines approved in the EU.

| Active substance | Reference product | Biosimilar medicines |

|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab (8) | Humira | Amgevita,[21] Amsparity,[22] Halimatoz,[23] Hefiya,[24] Hulio,[25] Hyrimoz,[26] Idacio,[27] Imraldi[28] |

| Bevacizumab (2) | Avastin | Mvasi, Zirabev |

| Enoxaparin sodium (1) | Lovenox | Inhixa |

| Epoetin alfa (5) | Eprex/Erypo | Abseamed, Binocrit, Epoetin Alfa Hexal, Retacrit, Silapo |

| Etanercept (3) | Enbrel | Benepali, Erelzi, Nepexto[29] |

| Filgrastim (7) | Neupogen | Accofil, Filgrastim Hexal, Grastofil, Nivestim, Ratiograstim, Tevagrastim, Zarzio |

| Follitropin alfa (2) | Gonal-F | Bemfola, Ovaleap |

| Infliximab (4) | Remicade | Flixabi, Inflectra, Remsima, Zessly |

| Insulin Aspart (1) | Novo Rapis | Insulin Aspart Sanofi (pos.opinion.) |

| Insulin glargine (2) | Lantus | Abasaglar, Semglee |

| Insulin lispro (1) | Humalog | Insulin lispro Sanofi |

| Pegfilgrastim (7) | Neulasta[30] | Cegfila,[31] Fulphila,[32] Grasustek,[33] Pelgraz,[34] Pelmeg,[35] Udenyca,[36] Ziextenzo[37] |

| Rituximab (6) | MabThera | Blitzima, Ritemvia, Rixathon, Riximyo, Ruxience, Truxima |

| Somatropin (1) | Genotropin | Omnitrope[38] |

| Teriparatide (2) | Forsteo | Movymia, Terrosa |

| Trastuzumab (5) | Herceptin | Ontruzant, Herzuma, Kanjinti, Trazimera, Ogivri |

Source: European Medicines Agency (June 2020) https://www.biosimilars-nederland.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020_06_01-Table-EU-licensed-biosimilars-by-molecule_May_2020agv.pdf

United States

BPCI Act

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act) was originally sponsored and introduced on June 26, 2007, by Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA). It was formally passed under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPAC Act), signed into law by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010. The BPCI Act was an amendment to the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act) to create an abbreviated approval pathway for biological products that are demonstrated to be highly similar (biosimilar) to a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved biological product. The BPCI Act is similar, conceptually, to the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (also referred to as the "Hatch-Waxman Act") which created biological drug approval through the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFD&C Act). The BPCI Act aligns with the FDA's longstanding policy of permitting appropriate reliance on what is already known about a drug, thereby saving time and resources and avoiding unnecessary duplication of human or animal testing. The FDA has released a total of four draft guidelines related to biosimilar or follow-on biologics development. Upon the release of the first three guidance documents the FDA held a public hearing on May 11, 2012.[39]

In 2018, the FDA released a Biosimilars Action Plan to implement regulations from the BPCI, including limiting the abuse of the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) system for evergreening and transitioning insulin and human growth hormone to regulation as biologics rather than drugs.[40]

US approved biosimilars

| Date of Biosimilar FDA Approval | Biosimilar Product | Original Product |

|---|---|---|

| March 6, 2015[41] | filgrastim-sndz/Zarxio | filgrastim/Neupogen |

| April 5, 2016[42] | infliximab-dyyb/Inflectra | infliximab/Remicade |

| August 30, 2016[43] | etanercept-szzs/Erelzi | etanercept/Enbrel |

| September 23, 2016[44] | adalimumab-atto/Amjevita | adalimumab/Humira |

| April 21, 2017[45] | infliximab-abda/Renflexis | infliximab/Remicade |

| August 25, 2017[46] | adalimumab-adbm/Cyltezo | adalimumab/Humira |

| September 14, 2017[47] | bevacizumab-awwb/Mvasi | bevacizumab/Avastin |

| December 1, 2017[48] | trastuzumab-dkst/Ogivri | trastuzumab/Herceptin |

| December 13, 2017[49] | infliximab-qbtx/Ixifi | infliximab/Remicade |

| May 15, 2018[50] | epoetin alfa-epbx/Retacrit | epoetin alfa/Procrit |

| June 4, 2018[51] | pegfilgrastim-jmdb/Fulphila | pegfilgrastim/Neulasta |

| July 20, 2018[52] | filgrastim-aafi/Nivestym | filgrastim/Neupogen |

| October 30, 2018[53] | adalimumab-adaz/Hyrimoz | adalimumab/Humira |

| November 2, 2018[54] | pegfilgrastim-cbqv/Udenyca | pegfilgrastim/Neulasta |

| November 28, 2018[55][56][57] | rituximab-abbs/Truxima | rituximab/Rituxan |

| December 14, 2018[58] | trastuzumab-pkrb/Herzuma | trastuzumab/Herceptin |

| January 18, 2019[59] | trastuzumab-dttb/Ontruzant | trastuzumab/Herceptin |

| March 11, 2019[60] | trastuzumab-qyyp/Trazimera | trastuzumab/Herceptin |

| April 25, 2019[61] | etanercept-ykro/Eticovo | etanercept/Enbrel |

| June 13, 2019[62] | trastuzumab-anns/Kanjinti | trastuzumab/Herceptin |

| June 27, 2019[63] | bevacizumab-bvzr/Zirabev | bevacizumab/Avastin |

| July 23, 2019[64] | rituximab-pvvr/Ruxience | rituximab/Rituxan |

| July 23, 2019[65] | adalimumab-bwwd/Hadlima | adalimumab/Humira |

| November 4, 2019[66] | pegfilgrastim-bmez/Ziextenzo | pegfilgrastim/Neulasta |

| November 15, 2019[67] | adalimumab-afzb/Abrilada | adalimumab/Humira |

| December 6, 2019[68] | infliximab-axxq/Avsola | infliximab/Remicade |

| June 10, 2020[69] | pegfilgrastim-apgf/Nyvepria | pegfilgrastim/Neulasta |

Nomenclature

In Europe no unique identifier of a biosimilar medicine product is required, same rules are followed as for all biologics. For identifying and tracing biological medicines in the EU, medicines have to be distinguished by the tradename and batch number and this is particularly important in cases where more than one medicine with the same INN exists on the market. This ensures that, in line with EU requirements for ADR reporting, the medicine can be correctly identified if any product-specific safety (or immunogenicity) concern arises.[70] The report 1 of the May 2017 WHO Expert Consultation on Improving Access to and Use of Similar Biotherapeutic Products, published in October 2017, revealed on page 4, that following the outcome arising from the meeting: "No consensus was reached on whether WHO should continue with the BQ...WHO will not be proceeding with this at present."[71] On 14 February 2019, Health Canada announced the decision that both the brand name and non-proprietary name should be used throughout the medication use process. Biologics that share the same non-proprietary name can be distinguished by their unique brand names .[72] The US decided on a different approach, being only jurisdiction requiring the assignment of a four character alphabetic suffix to the nonproprietary name of the original product to distinguish between innovator drugs and their biosimilars.[73]

Proposed reforms

In the United States, biosimilars have not had the expected impact on prices, leading a 2019 proposal to price regulate instead after an exclusivity period.[74] Another proposal requires originators to share the underlying cell lines.[75]

In 2019, the proposed Biologic Patent Transparency Act would help address evergreening "patent thickets" by requiring that all patents protecting a biosimilar be disclosed.[76]

Biosimilars have found it difficult to get market share, which led biosimilar developer Pfizer to sue Johnson & Johnson over anticompetitive contracts with pharmacy benefit managers which bundle discounts;[77] these are sometimes called the "rebate wall", and the rebates are generally unavailable to customers.[78]

A proposed rule affecting Medicare / Medicaid enrollees announced later in 2019[79] A proposed law entitled Prescription Pricing for the People Act of 2019 was introduced requesting that the FTC investigate rebating.[80] In 2019, pharmaceuticals CEOs testified before a Senate committee, with companies disagreeing on biosimilar competition reform.[81] The House Oversight Committee and Senate Finance Committee both held hearings in early 2019.[82]

Market implications

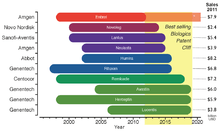

The legal requirements of approval pathways, together with the costly manufacturing processes, escalates the developing costs for biosimilars that could be between $75–$250 million per molecule.[83] This market entry barrier affects not only the companies willing to produce them but could also delay availability of inexpensive alternatives for public healthcare institutions that subsidize treatment for their patients. Even though the biosimilars market is rising, the price drop for biological drugs at risk of patent expiration will not be as great as for other generic drugs; in fact it has been estimated that the price for biosimilar products will be 65%-85% of their originators.[83] Biosimilars are drawing market's attention since there is an upcoming patent cliff, which will put nearly 36% of the $140 billion market for biologic drugs at risk (as of 2011), this considering only the top 10 selling products.[83]

The global biosimilars market was US$1.3 billion in 2013 and is expected to reach US$35 billion by 2020 driven by the patent expiration of additional ten blockbuster biologic drugs.[84][85]

Companies

Certain companies (in some cases subsidiaries) tend to operate as generic drug manufacturers, with major ones including Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz[86] and may also extend that focus to biosimilars. Sandoz, for example, introduced the first biosimilar in the United States, and plans to introduce another in 2020.[87] Newer companies such as India-based Sun Pharma, Aurobindo Pharma, and Dr. Reddy's Laboratories as well as Canada-based Apotex have taken share in traditional generics, which has led older companies to shift their focus to complex drugs such as biosimilars.[88]

References

- "Biosimilar medicines: Overview". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Nick, C (2012). "The US Biosimilars Act: Challenges Facing Regulatory Approval". Pharm Med. 26 (3): 145–152. doi:10.1007/bf03262388.

- Lamanna WC, Holzmann J, Cohen HP, Guo X, Schweigler M, Stangler T, Seidl A, Schiestl M (April 2018). "Maintaining consistent quality and clinical performance of biopharmaceuticals". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 18 (4): 369–379. doi:10.1080/14712598.2018.1421169. PMID 29285958.

- Guidelines on evaluation of similar Biotherapeutic Products (SBPs) (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 2009.

- Guidelines on evaluation of similar Biotherapeutic Products (SBPs), Annex 2, Technical Report Series No. 977 (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 2013.

- WHO Questions and Answers: Similar Biotherapeutic Products (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 2018.

- Guidelines on evaluation of monoclonal antibodies as similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs), Annex 2, Technical Report Series No. 1004 (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 2017.

- (PDF) https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Testimony of Dr. Lester Crawford, Acting Commissioner, FDA June 23, 2004". Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- Hearing: Assessing the Impact of a Safe and Equitable Biosimilar Policy in the United States. Subcommittee on Health Wednesday, May 2, 2007 Archived September 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "FDA page on "Follow-On Protein Products: Regulatory and Scientific Issues Related to Developing"".

- "FDA page on "Approval Pathway for Biosimilar and Interchangeable Biological Products Public Meeting"".

- "FDA Response to three Citizen Petitions against biosimilars" (PDF).

- "FDA page on "FDA approves first biosimilar product Zarxio"".

- "Statement on low-cost biosimilar and interchangeable protein products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Weise M, Kurki P, Wolff-Holz E, Bielsky MC, Schneider CK (November 2014). "Biosimilars: the science of extrapolation". Blood. 124 (22): 3191–6. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-06-583617. PMID 25298038.

- EMEA guideline on similar biological medicinal products Archived June 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Warren JB (January 2013). "Generics, chemisimilars and biosimilars: is clinical testing fit for purpose?". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 75 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04323.x. PMC 3555041. PMID 22574725.

- Wang, X. (June 1, 2014). "Higher-Order Structure Comparability: Case Studies of Biosimilar Monoclonal Antibodies". BioProcess International. 12 (6): 32–37.

- Declerck PJ (February 2013). "Biosimilar monoclonal antibodies: a science-based regulatory challenge". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 13 (2): 153–6. doi:10.1517/14712598.2012.758710. PMID 23286777.

- "Amgevita". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Amsparity". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Halimatoz". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Hefiya". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Hulio". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Hyrimoz". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Idacio". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Imraldi". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Nepexto EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 24 March 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Neulasta". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Cegfila (previously Pegfilgrastim Mundipharma)". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Fulphila". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Grasustek". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Pelgraz". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Pelmeg". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Udenyca". European Medicines Agency (EMA. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Ziextenzo". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Omnitrope". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Epstein MS, Ehrenpreis ED, Kulkarni PM (December 2014). "Biosimilars: the need, the challenge, the future: the FDA perspective" (PDF). The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 109 (12): 1856–9. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.151. PMID 24957160. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- "Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new actions advancing the agency's biosimilars policy framework". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Retrieved 2018-12-16.

- "Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 April 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "FDA approves Inflectra, a biosimilar to Remicade". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release).

- "FDA approves Erelzi, a biosimilar to Enbrel". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release).

- "FDA approves Amjevita, a biosimilar to Humira". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release).

- "Drug Approval Package: Renflexis (infliximab-abda)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 10 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- "FDA approves first biosimilar for the treatment of cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release).

- "FDA approves first biosimilar for the treatment of certain breast and stomach cancers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release).

- "Drug Approval Package: Ixifi (infliximab-qbtx)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 November 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "FDA approves first epoetin alfa biosimilar for the treatment of anemia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release).

- "FDA approves first biosimilar to Neulasta to help reduce the risk of infection during cancer treatment". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release).

- "Drug Approval Package: Nivestym (filgrastim-aafi)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 February 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Hyrimoz". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 March 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Udenyca". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 5 March 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "FDA approves Truxima as biosimilar to Rituxan for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Press release). 28 November 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "FDA approves first biosimilar for treatment of adult patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 28 November 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Truxima (rituximab-abbs)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 25 February 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Herzuma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 7 February 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Ontruzant (trastuzumab-dttb)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 5 March 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Trazimera (trastuzumab-qyyp)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Eticovo". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 18 June 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Kanjinti". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 18 July 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Zirabev". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 14 August 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Ruxience". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 9 August 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Hadlima". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 5 September 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Ziextenzo". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Abrilada". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Avsola". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Nyvepria". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Biosimilars in the EU: Information guide for healthcare professionals" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "WHO Report on the Expert Consultation on Improving Access to and Use of Similar Biotherapeutic Products" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "Notice to Stakeholders - Policy Statement on the Naming of Biologic Drugs". Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products; Draft Guidance for Industry; Availability". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- says, William Smith (2019-04-15). "Peter Bach's crazy idea: Give up on biosimilars. Regulate prices instead". STAT. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- Gotham D (2018-05-03). "Cell line access to revolutionize the biosimilars market". F1000Research. 7: 537. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14808.1. PMC 6051195. PMID 30057752.

- "Will The Biologic Patent Transparency Act Shrink The Biosimilar Patent Dance Floor?". The National Law Review. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- "Focus on Competition in U.S. Biosimilars Market Heats Up in Summer of 2018". JD Supra. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- "'Rebate walls' for drugs should be dismantled by the FTC". STAT. 2018-12-04. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- Roy, Avik. "Trump's New Pharmacy Benefit Manager Rebate Rule Will Reshape Prescription Drug Prices". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- Staff, Tacoma Weekly. "The Prescription Pricing for the People Act of 2019". Tacoma Weekly. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- "At Senate hearing, pharma shows split on biosimilars". BioPharma Dive. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- "House committee weighs drug pricing proposals". Endpoints News. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- Calo-Fernández B, Martínez-Hurtado JL (December 2012). "Biosimilars: company strategies to capture value from the biologics market". Pharmaceuticals. 5 (12): 1393–408. doi:10.3390/ph5121393. PMC 3816668. PMID 24281342.

- "Biosimilars and Follow-on-Biologics Market to Hit $35 Billion Globally by 2020". Pharmaceutical Technology. 28 August 2015.

- Bali, Vikram (May 25, 2017). "Important Considerations When Sourcing Reference Products For Biosimilar Studies". Clinical Leader. VertMarkets. Retrieved 17 Dec 2019.

As a slew of the most important, most widely-used and accepted biologics have their patents expire this decade, the biosimilar market is predicted to leap from $1.36 billion in 2013 to over $35 billion by 2020 (Allied Market Research).

- Stone, Kathlyn. "What Are the Top Generic Drug Companies?". The Balance. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- biopharma-reporter.com. "Biosimilar entry into US insulin market will see 'millions more patients treated'". biopharma-reporter.com. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- "'Old guard' generics players yield U.S. lead to Indian up-and-comers: analyst". FiercePharma. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

Further reading

- Udpa N, Million RP (January 2016). "Monoclonal antibody biosimilars". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 15 (1): 13–4. doi:10.1038/nrd.2015.12. PMID 26678619.

- Jelkmann W (October 2010). "Biosimilar epoetins and other "follow-on" biologics: update on the European experiences". American Journal of Hematology. 85 (10): 771–80. doi:10.1002/ajh.21805. PMID 20706990.

- "New guide on biosimilar medicines for healthcare professionals". Prepared Jointly by the European Medicines Agency and the European Commission. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/whats-keeping-generic-version-biologic-drugs-u-s-market/

- Therapeutics, Initiative (November 2019). "Biosimilars or Biologics: What's the difference?". Therapeutics Letter 123.