Biolinguistics

Biolinguistics can be defined as the study of biology and the evolution of language. It is a highly interdisciplinary as it related to various fields such as biology, linguistics, psychology, mathematics, and neurolinguistics to explain the formation of language. It is important as it seeks to yield a framework by which we can understand the fundamentals of the faculty of language. This field was first introduced by Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, professor of Linguistics and Cognitive Science at the University of Arizona. It was first introduced in 1971, at an international meeting at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Biolinguistics, also called the biolinguistic enterprise or the biolinguistic approach, is believed to have its origins in Noam Chomsky’s and Eric Lenneberg’s work on language acquisition that began in the 1950s as a reaction to the then-dominant behaviorist paradigm. Fundamentally, biolinguistics challenges the view of human language acquisition as a behavior based on stimulus-response interactions and associations.[1] Chomsky and Lenneberg militated against it by arguing for the innate knowledge of language. Chomsky in 1960s proposed the Language Acquisition Device (LAD) as a hypothetical tool for language acquisition that only humans are born with. Similarly, Lenneberg (1967)[2] formulated the Critical Period Hypothesis, the main idea of which being that language acquisition is biologically constrained. These works were regarded as pioneers in the shaping of biolinguistic thought, in what was the beginning of a change in paradigm in the study of language.[3]

Origins

Darwinism inspired many researchers to study language, in particular the evolution of language, mainly by means of biology. Darwin's theory regarding the origin of language attempts to answer two important questions i) Whether individuals undergo something like selection as they evolve, and ii) selection played a role in producing the power of articulate language in humans; and, if it did, whether the selection was primarily responsible for the emergence of that power or just one of the several contributing causes. [4]Dating all the way back to 1821, German linguist August Scheilurer was the representative pioneer of biolinguistics, discussing the evolution of language based on Darwin’s theory of evolution. Since linguistics had been believed to be a form of historical science under the influence of the Société de Linguistique de Paris, speculations of the origin of language were not permitted.[5] As a result, hardly did any prominent linguist write about the origin of language apart from German linguist Hugo Schuchardt. Darwinism addressed the arguments of other researchers and scholars much as Max Müller by arguing that language use, while requiring a certain mental capacity, also stimulates brain development, enabling long trains of thought and strengthening power. Darwin drew an extended analogy between the evolution of languages and species, noting in each domain the presence of rudiments, of crossing and blending, and variation, and remarking on how each development gradually through a process of struggle.[6]

The first phase in the development of biolinguistics runs through the late 1960's with the publication of Lennberg's Biological Foundation of Language (1967). The range of topics under active investigation on the biology of language during this period included: language acquisition, genetics of language disorders (dyslexia, specific language disabilities, deaf children), and the evolution of language. During the first phase work was carried out in three specific areas; language, development of language, and, evolution of language. The greatest progress was made in the area regarding the specifying the notion on language.

The first official biolinguistic conference was organized by him in 1974, bringing together evolutionary biologists, neuroscientists, linguists, and others interested in the development of language in the individual, its origins and evolution.[7] In 1976, another conference was held by the New York Academy of Science, after which numerous works on the origin of language were published.[8] In 1997, for the 40th anniversary of transformational-generative grammar, Lyle Jenkins wrote an article titled "Biolinguistics: Structure development and evolution of language".[9] The second phase began in the late 1970's . In 1976 Chomsky formulated the fundamental questions of biolingusitcs as follows: i) function, ii) structure, iii) physical basis, iv) development in the individual, v) evolutionary development. In the late 1980's a great deal of progress was made in answering question about the development of language. This then prompted further questions about language design. function, and, the evolution of language. The following year, Juan Uriagereka, a graduate student of Howard Lasnik, wrote the introductory text to Minimalist Syntax, Rhyme and Reason. Their work renewed interest in biolinguistics, catalysing many linguists to look into biolinguistics with their colleagues in adjacent scientific disciplines.[10] Both Jenkins and Uriagereka stressed the importance of addressing the emergence of the language faculty in humans. At around the same time, geneticists discovered a link between the language deficit manifest by the KE family members and the gene FOXP2. Although FOXP2 is not the gene responsible for language,[11] this discovery brought many linguists and scientists together to interpret this data, renewing the interest of biolinguistics.

Although many linguists have differing opinions when it comes to the history of biolinguistics, Chomsky believes that its history was simply that of transformational grammar. While Professor Anna Maria Di Sciullo claims that the interdisciplinary research of biology and linguistics in the 1950s-1960s led to the rise of biolinguistics. Furthermore, Jenkins believes that biolinguistics was the outcome of transformational grammarians studying human linguistic and biological mechanism. On the other hand, linguists Martin Nowak and Charles Yang argue that biolinguistics, originating in the 1970s, is distinct transformational grammar; rather a new branch of the linguistics-biology research paradigm initiated by transformational grammar.[12]

Developments

Chomsky's Theories

Universal Grammar and Generative Grammar

[13] In Aspects of the theory of Syntax, Chomsky proposed that languages are the product of a biologically determined capacity present in all humans, located in the brain. He addresses three core questions of biolinguistics: what constitutes the knowledge of language, how is knowledge acquired, how is the knowledge put to use? A great deal of our must be innate, supporting his claim with the fact that speakers are capable of producing and understanding novel sentences without explicit instructions. Chomsky proposed that the form of the grammar may merge from the mental structure afforded by the human brain and argued that formal grammatical categories such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives do not exist. The linguistic theory of generative grammar thereby proposes that sentences are generated by a subconscious set of procedures which are part of an individual’s cognitive ability. These procedures are modeled through a set of formal grammatical rules which are thought to generate sentences in a language.[14]

Chomsky focuses on the mind of the language learner or user and proposed that internal properties of the language faculty are closely linked to the physical biology of humans. He further introduced the idea of a Universal Grammar (UG) theorized to be inherent to all human beings. UG refers to the initial state of the faculty of language; a biologically innate organ that helps the learner make sense of the data and build up an internal grammar.[15] The theory suggests that all human languages are subject to universal principles or parameters that allow for different choices (values). It also contends that humans possess generative grammar, which is hard-wired into the human brain in some ways and makes it possible for young children to do the rapid and universal acquisition of speech.[16] Elements of linguistic variation then determine the growth of language in the individual, and variation is the result of experience, given the genetic endowment and independent principles reducing complexity. Chomsky's work is often recognized as the weak perspective of biolinguistics as it does not pull from other fields of study outside of linguistics.[17]

Language Acquisition Device

The acquisition of language is a universal feat and it is believed we are all born with an innate structure initially proposed by Chomsky in the 1960s. The Language Acquisition Device (LAD) was presented as an innate structure in humans which enabled language learning. Individuals are thought to be “wired” with universal grammar rules enabling them to understand and evaluate complex syntactic structures. Proponents of the LAD often quote the argument of the poverty of negative stimulus, suggesting that children rely on the LAD to develop their knowledge of a language despite not being exposed to a rich linguistic environment. Later, Chomsky exchanged this notion instead for that of Universal Grammar, providing evidence for a biological basis of language.

Minimalist Program

The Minimalist Program (MP) was introduced by Chomsky in 1993, and it focuses on the parallel between language and the design of natural concepts. Those invested in the Minimalist Program are interested in the physics and mathematics of language and its parallels with our natural world. For example, Piatelli-Palmarini [18] studied the isomorphic relationship between the Minimalist Program and Quantum Field Theory. The Minimalist Program aims to figure out how much of the Principles and Parameters model can be taken as a result of the hypothetical optimal and computationally efficient design of the human language faculty and more developed versions of the Principles and Parameters approach in turn provide technical principles from which the minimalist program can be seen to follow.[19] The program further aims to develop ideas involving the economy of derivation and economy of representation, which had started to become an independent theory in the early 1990s, but were then still considered as peripherals of transformational grammar.[20]

The Merge operation is used by Chomsky to explain the structure of syntax trees within the Minimalist program. Merge itself is a process which provides the basis of phrasal formation as a result of taking two element within a phrase and combining them[21] In A.M. Di Sciullo & D. Isac's The Asymmetry of Merge (2008), they highlight the two key bases of Merge by Chomsky;

- Merge is binary

- Merge is recursive

In order to understand this, take the following sentence: Emma dislikes pies

This phrase can be broken down into its lexical items:

[VP [DP Emma] [V' [V dislikes] [DP [D the] [NP pie]]]

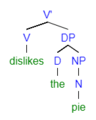

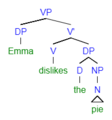

The above phrasal representation allows for an understanding of each lexical item. In order to build a tree using Merge, using bottom-up formation the two final element of the phrase are selected and then combined to form a new element on the tree. In image a) you can see that the determiner the and the Noun Phrase pie are both selected. Through the process of Merge, the new formed element on the tree is the determiner Phrase (DP) which holds, the pie, which is visible in b).

a) Selection of the final two element of the phrase

a) Selection of the final two element of the phrase b) The two selected elements are then "merged" and they produce one new constituent, known as the Determiner Phrase (DP)

b) The two selected elements are then "merged" and they produce one new constituent, known as the Determiner Phrase (DP) c) Selection of DP the pie with V dislikes

c) Selection of DP the pie with V dislikes d) Merge operation has occurred, yielded new element on tree, V' (V-bar)

d) Merge operation has occurred, yielded new element on tree, V' (V-bar) e) Selection of V' dislikes the pie and DP subject Emma

e) Selection of V' dislikes the pie and DP subject Emma f) Merge operation has undergone, yielded new element on tree; VP

f) Merge operation has undergone, yielded new element on tree; VP

In a minimalist approach, there are three core components of the language faculty proposed: Sensory-Motor system (SM), Conceptual-Intentional system (CI), and Narrow Syntax (NS).[22] SM includes biological requisites for language production and perception, such as articulatory organs, and CI meets the biological requirements related to inference, interpretation, and reasoning, those involved in other cognitive functions. As SM and CI are finite, the main function of NS is to make it possible to produce infinite numbers of sound-meaning pairs.

Relevance of Natural Law

It is possible that the core principles of The Faculty of Language be correlated to natural laws (such as for example, the Fibonacci sequence— an array of numbers where each consecutive number is a sum of the two that precede it, see for example the discussion Uriagereka 1997 and Carnie and Medeiros 2005).[23] According to the hypothesis being developed, the essential properties of language arise from nature itself: the efficient growth requirement appears everywhere, from the pattern of petals in flowers, leaf arrangements in trees and the spirals of a seashell to the structure of DNA and proportions of human head and body. Natural Law in this case would provide insight on concepts such as binary branching in syntactic trees and well as the Merge operation. This would translate to thinking it in terms of taking two elements on a syntax tree and such that their sum yields another element that falls below on the given syntax tree (Refer to trees above in Minimalist Program). By adhering to this sum of two elements that precede it, provides support for binary structures. Furthermore, the possibility of ternary branching would deviate from the Fibonacci sequence and consequently would not hold as strong support to the relevance of Natural Law in syntax.[24]

Biolinguistics: Challenging the Usage-Based Approach

As mentioned above, biolinguistics challenges the idea that the acquisition of language is a result of behavior based learning. This alternative approach the biolinguistics challenges is known as the usage-based (UB) approach. UB supports that idea that knowledge of human language is acquired via exposure and usage [25]. One of the primary issues that is highlighted when arguing against the Usage-Based approach, is that UB fails to address the issue of poverty of stimulus[26], whereas biolinguistics addresses this by way of the Language Acquisition Device.

Lenneberg and the Role of Genes

Another major contributor to the field is Eric Lenneberg. In is book Biological Foundation of Languages,[2] Lenneberg (1967) suggests that different aspects of human biology that putatively contribute to language more than genes at play. This intergration of other fields to explain language is recognized as the strong view in biolinguistics[27] While they are obviously essential, and while genomes are associated with specific organisms, genes do not store traits (or “faculties”) in the way that linguists—including Chomskyans—sometimes seem to imply.

Contrary to the concept of the existence of a language faculty as suggested by Chomsky, Lenneberg argues that while there are specific regions and networks crucially involved in the production of language, there is no single region to which language capacity is confined and that speech, as well as language, is not confined to the cerebral cortex. Lenneberg considered language as a species-specific mental organ with significant biological properties. He suggested that this organ grows in the mind/brain of a child in the same way that other biological organs grow, showing that the child’s path to language displays the hallmark of biological growth. According to Lenneberg, genetic mechanisms plays an important role in the development of an individual’s behavior and is characterized by two aspects:

- The acknowledgement of an indirect relationship between genes and traits, and;

- The rejection of the existence of ‘special’ genes for language, that is, the rejection of the need for a specifically linguistic genotype;

Based on this, Lenneberg goes on further to claim that no kind of functional principle could be stored in an individual’s genes, rejecting the idea that there exist genes for specific traits, including language. In other words, that genes can contain traits. He then proposed that the way in which genes influence the general patterns of structure and function is by means of their action upon ontogenesis of genes as a causal agent which is individually the direct and unique responsible for a specific phenotype, criticizing prior hypothesis by Charles Goodwin.[28]

Recent Developments

Generative Procedure Accepted At Present & Its Developments

In biolinguistics, language is recognised to be based on recursive generative procedure that retrieves words from the lexicon and applies them repeatedly to output phrases. This generative procedure was hypothesised to be a result of a minor brain mutation due to evidence that word ordering is limited to externalisation and plays no role in core syntax or semantics. Thus, different lines of inquiry to explain this were explored.

The most commonly accepted line of inquiry to explain this is Noam Chomsky's minimalist approach to syntactic representations. In 2016, Chomsky and Berwick defined the minimalist program under the Strong Minimalist Thesis in their book Why Only Us by saying that language is mandated by efficient computations and, thus, keeps to the simplest recursive operations.[11] The main basic operation in the minimalist program is merge. Under merge there are two ways in which larger expressions can be constructed: externally and internally. Lexical items that are merged externally build argument representations with disjoint constituents. The internal merge creates constituent structures where one is a part of another. This induces displacement, the capacity to pronounce phrases in one position, but interpret them elsewhere.

Recent investigations of displacement concur to a slight rewiring in cortical brain regions that could have occurred historically and perpetuated generative grammar. Upkeeping this line of thought, in 2009, Ramus and Fishers speculated that a single gene could create a signalling molecule to facilitate new brain connections or a new area of the brain altogether via prenatally defined brain regions. This would result in information processing greatly important to language, as we know it. The spread of this advantage trait could be responsible for secondary externalisation and the interaction we engage in.[11] If this holds, then the objective of biolinguistics is to find out as much as we can about the principles underlying mental recursion.

Human versus Animal Communication

Compared to other topics in linguistics where data can be displayed with evidence cross-linguistically, due to the nature of biolinguistics, and that it is applies to the entirety of linguistics rather than just a specific subsection, examining other species can assist in providing data. Although animals do not have the same linguistic competencies as humans, is it assumed that they can provide evidence for some linguistic competence.

The relatively new science of evo-devo that suggests everyone is a common descendant from a single tree has opened pathways into gene and biochemical study. One way in which this manifested within biolinguistics is through the suggestion of a common language gene, namely FOXP2. Though this gene is subject to debate, there have been interesting recent discoveries made concerning it and the part it plays in the secondary externalization process. Recent studies of birds and mice resulted in an emerging consensus that FOXP2 is not a blueprint for internal syntax nor the narrow faculty of language, but rather makes up the regulatory machinery pertaining to the process of externalization. The fact that it has been found to assists sequencing sound or gesture one after the next, hence implying that FOXP2 helps transfer knowledge from declarative to procedural memory. Therefore, FOXP2 has been discovered to be an aid in formulating a linguistic input-output system that runs smoothly.[11]

Critiques

Alternative Theoretical Approaches

Stemming from the usage-based approach, the Competition Model, developed by Elizabeth Bates and Brian MacWhinney, views language acquisition as consisting of a series of competitive cognitive processes that act upon a linguistic signal. This suggests that language development depends on learning and detecting linguistic cues with the use of competing general cognitive mechanisms rather than innate, language-specific mechanisms.

From the side of biosemiotics, the has been a recent claim that meaning-making begins far before the emergence of human language. This meaning-making consists internal and external cognitive processes. Thus, it holds that such process organisation could not have only given a rise to language alone. According to this perspective all living things possess these processes, regardless of how wide the variation, as a posed to species-specific.[29]

Over-Emphasised Weak Stream Focus

When talking about biolinguistics there are two senses that are adopted to the term: strong and weak biolinguistics. The weak is founded on theoretical linguistics that is generativist in persuasion. On the other hand, the strong stream goes beyond the commonly explored theoretical linguistics, with an oriented towards biology, as well as other relevant fields of study. Since the early emergence of biolinguistics to its present day, there has been a focused mainly on the weak stream, seeing little difference between the inquiry into generative linguistics and the biological nature of language as well as heavily relying on the Chomskyan origin of the term.[30]

As expressed by research professor and linguist Cedric Boeckx, it is a prevalent opinion that biolinguistics need to focus on biology as to give substance to the linguistic theorizing this field has engaged in. Particular criticisms mentioned include a lack of distinction between generative linguistics and biolinguistics, lack of discoveries pertaining to properties of grammar in the context of biology, and lack of recognition for the importance broader mechanisms, such as biological non-linguistic properties. After all, it is only advantage to label propensity for language as biological if such insight is used towards a research.[30]

David Poeppel, a neuroscientist and linguist, has additionally noted that if neuroscience and linguistics are done wrong, there is a risk of "inter-disciplinary cross-sterilization," arguing that there is a Granularity Mismatch Problem. Due to this different levels of representations used in linguistics and neural science lead to vague metaphors linking brain structures to linguistic components. Poeppel and Embick also introduce the Ontological Incommensurability Problem, where computational processes described in linguistic theory cannot be restored to neural computational processes.[31]

A recent critique of biolinguistics and 'biologism' in language sciences in general was developed by Prakash Mondal who shows that there are inconsistencies and categorical mismatches in any putative bridging constraints that purport to relate neurobiological structures and processes to the logical structures of language that have a cognitive-representational character.[32]

Other Relevant Fields

| Topic | Description | Relevance to Biolinguistics |

|---|---|---|

| Neurolinguistics | The study of how language is represented in the brain; closely tied to psycholinguistics, language acquisition, and the localisation of the language process. | Physiological mechanisms by which the brain processes in formation related to language. |

| Language Acquisition | The way in which humans learn to perceive, produce and comprehend language;[33] guided by Universal Grammar proposed by Chomsky; children's ability to learn properties of grammar from impoverished linguistic data.[34] | Language growth and maturation in individuals; evolutionary processes that led to the emergence of language; poverty of the stimulus.[35][9] |

| Linguistic Typology | The analysis, comparison, and classification of languages according to their common structural features;[36] | Identifies similarities and differences in the languages of the world; suggests languages may not be completely random. |

| Syntax | The rules that govern the grammatical organization of words and phrases. | Generative grammar; poverty of the stimulus; structure dependency whereby a sentence is influenced its structure and not just the order of words.[37] |

| Artificial Grammar Learning | The intersection between cognitive psychology and linguistics | Humans' cognitive processes and pattern-detection in a language learning context; how humans learn and interpret grammar. |

Researchers in Biolinguistics

- Alec Marantz, NYU/MIT

- Andrew Carnie, University of Arizona

- Anna Maria Di Sciullo, University of Quebec at Montreal

- Antonio-Benitez Burraco, University of Seville

- Cedric Boeckx, Catalan institute for Advanced Studies

- Charles Reiss, Concordia University

- David Poeppel, NYU

- Derek Bickerton, University of Hawaii

- Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, University of Arizona

- Michael Arbib, University of Southern California

- Philip Lieberman, Brown University

- Ray C. Dougherty, New York University (NYU)

- W. Tecumseh Fitch, University of Vienna

See also

References

- DEMIREZEN, Mehmet (1988). "Behaviorist theory and language learning". Hacettepe üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Öğretim üyesi. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/88422

- Lenneberg, E.H. (1967). Biological foundations of language. New York Wiley.

- Martins, Pedro Tiago; Boeckx, Cedric (27 August 2016). "What we talk about when we talk about biolinguistics". Linguistics Vanguard. 2 (1). doi:10.1515/lingvan-2016-0007.

- Radick, Gregory (November 2002). "Darwin on Language and Selection". Selection. 3 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1556/Select.3.2002.1.2. S2CID 36616051.

- Trabant, Jürgen (2001). New essays on the origin of language. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110849080.

- Plotkin, Henry (25 April 1997). Darwin Machines and the Nature of Knowledge. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674192812.

- Boeckx, Cedric; Piattelli-Palmarini, Massimo (2005). "Language as a natural object, linguistics as a natural science. Linguistic Review 22: 447–466" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-23. Retrieved 2014-09-15.

- "Origins and evolution of language and speech". Journal of Human Evolution. 8 (2): 309–310. February 1979. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(79)90104-0. ISSN 0047-2484.

- Jenkins, Jennifer (1997). "Biolinguistics-structure, development and evolution of language". Web Journal of Formal, Computational and Cognitive Linguistics. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.35.1374.

- Di Sciullo, Anna Maria; Boeckx, Cedric (2011). The Biolinguistic Enterprise: New Perspectives on the Evolution and Nature of the Human Language Faculty Volume 1 of Oxford Studies in Biolinguistics. Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 9780199553273.

- Why Only Us. The MIT Press. 2016. doi:10.7551/mitpress/10684.001.0001. ISBN 9780262333351.

- Wu, Jieqiong (15 January 2014). An Overview of Researches on Biolinguistics. Canadian Social Science. pp. 171–176. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.820.7700.

- Wu, JIe Qiong (15 January 2014). An Overview of Researches on Biolinguistics. Canadian Social Science. pp. 171–176. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.820.7700.

- Freidin, Robert (5 March 2012). Generative Grammar: Theory and its History (1st ed.). Routledge Leading Linguists. ISBN 9780415541336.

- Călinescu, Mihaela (1 January 2012). "Chomsky's Biolinguistic Approach to Mind and Language". Linguistic & Philosophical Investigations. 11: 91–96.

- Logan, Robert K (2007). The extended mind : the emergence of language, the human mind, and culture. Toronto : University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802093035.

- Pleyer, Michael; Hartmann, Stefan (2019-11-14). "Constructing a Consensus on Language Evolution? Convergences and Differences Between Biolinguistic and Usage-Based Approaches". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 2537. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02537. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6868443. PMID 31803099.

- "Piatelli-Palmarini, M., & Vitello, G. (2017). "Quantum field theory and the linguistic Minimalist Program: a remarkable isomorphism"". Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- Gert Webelhuth. 1995. Government and Binding Theory and the Minimalist Program: Principles and Parameters in Syntactic Theory. Wiley-Blackwell; Uriagereka, Juan. 1998. Rhyme and Reason. An Introduction to Minimalist Syntax. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

- For a full description of the checking mechanism see Adger, David. 2003. Core Syntax. A Minimalist Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press; and also Carnie, Andrew. 2006. Syntax: A Generative Introduction, 2nd Edition. Blackwell Publishers

- Sciullo, Anna Maria Di; Isac, Daniela (2008-09-30). "The Asymmetry of Merge". Biolinguistics. 2 (4): 260–290. ISSN 1450-3417.

- Di Sciullo, Anna Maria; et al. (Winter 2010). "The Biological Nature of Human Language". Biolinguistics. 4. S2CID 141815607.

- Soschen, Alona (2006). "Natural Law: The Dynamics of Syntactic Representations in MP" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-21. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- Soschen, Alona (2008-03-25). "On the Nature of Syntax". Biolinguistics. 2 (2–3): 196–224. ISSN 1450-3417.

- Ibbotson, Paul (2013). "The Scope of Usage-Based Theory". Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 255. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00255. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 3647106. PMID 23658552.

- Ghalebi, Rezvan; Sadighi, Firooz (2015-08-06). "The Usage-based Theory of Language Acquisition: A review of Major Issues". Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research. 2 (6): 190–195. ISSN 2376-760X.

- Boeckx, Cedric; Grohmann, Kleanthes K. (2007). "The BIOLINGUISTICS Manifesto". Biolinguistics. 1: 001–008. ISSN 1450-3417.

- Boeckx, Cedric; Longa, Victor M. (2011). "Lenneberg's Views on Language Development and Evolution and Their Relevance for Modern Biolinguistics". Biolinguistics. 5 (3): 254–273. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Velmezova, Ekaterina; Kull, Kalevi; Cowley, Stephen (eds.) 2015. Biosemiotic Perspectives on Language and Linguistics. (Biosemiotics 13.) Cham: Springer.

- Martins, Pedro Tiago; Boeckx, Cedric (2016-12-01). "What we talk about when we talk about biolinguistics". Linguistics Vanguard. -1 (open–issue). doi:10.1515/lingvan-2016-0007.

- Poeppel, David; Embick, David (2005). "Defining the Relation Between Linguistics and Neuroscience". In Anne Cutler (ed.). Twenty-First Century Psycholinguistics: Four Cornerstones. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Mondal, Prakash. 2019: Language, Biology, and Cognition: A Critical Perspective.. Berlin/New York: Springer Nature.

- Lieberman, Philip (1984). The Biology and Evolution of Language. Harvard University.

- Sciullo, Anna Maria Di; Jenkins, Lyle (September 2016). "Biolinguistics and the human language faculty". Language. 92 (3): e205–e236. doi:10.1353/lan.2016.0056.

- Hickok, Greg (6 September 2009). "The functional neuroanatomy of language". Physics of Life Reviews. 6 (3): 121–43. Bibcode:2009PhLRv...6..121H. doi:10.1016/j.plrev.2009.06.001. PMC 2747108. PMID 20161054.

- Jenkins, Lyle (2000). Biolinguistics: Exploring the biology of language. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–108.

- Trudgill, Peter (2004). "The impact of language contact and social structure on linguistic structure: Focus on the dialects of modern Greek". Dialectology Meets Typology: Dialect Grammar from a Cross-linguistic Perspective. 153: 435–452.

Conferences

- Biolinguistic Investigations Conference, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, February 2007.

- Conference on Biolinguistics: Language Evolution and Variation, Università di Venezia, June 2007.

- ICREA International Symposium in Biolinguistics, Universitat de Barcelona, October 2012.

- The Journal of Biolinguistics