Benjamin Ratcliff

Benjamin Ratcliff (October 21, 1841 – February 7, 1896) was a homesteader near Jefferson in Park County in central Colorado, who was hanged for the murders of three members of his local school board with whom he had quarreled regarding the education of his children and slurs against his own reputation. One of the men he shot because the man spread rumors implying Benjamin impregnated his own handicapped teenaged daughter.

Benjamin Ratcliff | |

|---|---|

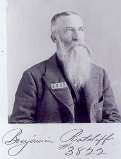

Ratcliff mug shot at Colorado State Penitentiary c. 1895 | |

| Born | October 21, 1841 |

| Died | February 7, 1896 (aged 54) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging for the murder of three local school board members |

| Resting place | Unknown location in Park County, Colorado |

| Occupation | Rancher |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Widower of Elizabeth McNair Ratcliff (married 1871–1882) |

| Children | 3 |

Background

Born in Hocking County in southern Ohio, Ratcliff was the sixth of ten children of Elias Ratcliff and the former Elizabeth Dutcher. The family, including his younger sister Mary, moved in 1844 to Moniteau County[1][2] near the capital city of Jefferson City in central Missouri. Elias died when Benjamin was ten years of age.[3]

In 1861, at the beginning of the American Civil War, Ratcliff at nineteen enlisted in the Missouri Home Guard Service.[1] A private in Company A of the 43rd Regiment Enrolled Missouri Militia, Ratcliff fought in the Battle of Shiloh, a Union victory in western Tennessee in early April 1862. While headed three weeks later to the Siege of Corinth in Corinth in northern Mississippi, Ratcliff's horse fell, tossed him from the saddle, and rolled onto Ratcliff's hip and legs. The accident caused a painful and permanent injury. During his life, Ratcliff had recurring hip problems, kidney stones,[1] and a dislocated shoulder sustained in an 1880 cattle roundup in Fairplay, the county seat of Park County, Colorado.[4]

In July 1862, he went to Jefferson City to join the regular United States Army.[5] In 1864, Ratcliff fought in the Second Battle of Lexington in Lexington in Lafayette County, Missouri. There he was captured by the Confederates, who were successful in that battle. He escaped two days later on his 23rd birthday.[6] While on the run, he spent a night hiding in a rut of wet grass, having recalled, "I took cold and the trouble has remained with me ever since."[1] Ratcliff managed to avoid the Missouri raid of Confederate General Sterling Price and spent the remainder of the war within Union lines about Jefferson City.[6]

From August 25 to November 1, 1862, Ratcliff was a federal hay inspector in the office of the Army quartermaster in Washington, D.C. In 1865, an Army surgeon who had treated Ratcliff for his recurring earlier wound sent him to the Rush Medical College in Chicago, where he remained for eighteen months. Ratcliff was urged to resettle in Colorado.[1] While subsequently in rehabilitation from the horse injury, Ratcliff was an internal revenue assessor in Denver from the summer of 1869 until November 1871.[7]

Relocation to Colorado

On June 10, 1871, while back in Moniteau County, Ratcliff, at twenty-nine, married his neighbor, Elizabeth McNair, who was some five years his senior.[8] Later in the year, the Ratcliffs took the train to Denver, the stagecoach to Colorado Springs, and then a wagon or horseback to the Tarryall Creek area of Park County. They established a successful homestead and ranch that remained in their family from purchase in 1876 until his arrest in 1895. Ratcliff reported to the 1885 Colorado census that he owned four horses, twenty dairy cows, thirty beef cattle, some seventy calves, and had produced that year 600 pounds (270 kg) of butter.[6]

In October 1882, Elizabeth Ratcliff and her fourth child died in childbirth. At forty-one, Ratcliff was left a widower to rear his son, Howell, and two daughters, Lizzie and Lavina. In 1884, he sent the daughters back to Missouri to live with relatives. Ratcliff and his son Howell, still a boy of ten, ran the ranch together. By 1892 or 1894, the girls returned to Colorado. Lizzie had a severe limp that had become permanent because of the lack of medical attention following a fall. One of her legs was 6 inches (150 mm) shorter than the other.[6]

Ratcliff in 1895 wrote George Miller, the superintendent of the Michigan Creek School Board, to request one of the following: (1) that the school be moved closer to the Ratcliff homestead, (2) that a special homebound teacher be assigned to assist him in the education of his children, or (3) that he be allowed to use the school textbooks and materials for home schooling. At the time, public school was held in Park County only in the winter, as children were needed for farm and ranch chores during the remainder of the year.[6] Ratcliff asked for the assistance to accommodate Lizzie's handicap because the school was 7 miles (11 km) away.[1] When the school board would not meet any of his requests, Ratcliff became frustrated, and events soon turned to disaster.[6]

Crime and punishment

Ratcliff received a letter on August 22, 1894, from his neighbor Susan M. Crockett,[1] which claimed that the 32-year-old school board president, Lincoln Fremont McCurdy, was spreading[6] false stories that one of the Ratcliff daughters was pregnant and that Ratcliff was himself the father of the unborn child.[9] Neither daughter was in fact pregnant. Beset by outrage, Ratcliff came to a school board meeting demanding a retraction of the rumor. He was armed with an 1873 Winchester rifle and two Colt 1851 Navy Revolvers, .36-caliber, which he had purchased in Fairplay c. 1881. Ratcliff claimed in his trial testimony that he fired the first shot as a warning.[1] He shot George Douglas Wyatt, the 35-year-old board treasurer, in the back. Wyatt died four hours later. He shot Samuel F. Taylor, the 56-year-old board secretary, in the face, and Lincoln McCurdy, twice in the chest. Taylor and McCurdy were killed instantly. Ratcliff and Taylor had served together on the county Republican caucus committee; Ratcliff had once nominated Taylor as the committee chairman.[10]

Ratcliff rode his horse into Fairplay and turned himself into the custody of Deputy Sheriff James A. Link.[1] Because of tensions stemming from the case in Fairplay, Ratcliff was tried in Buena Vista in Chaffee County.[11] Eleven defense witnesses testified for Ratcliff, including his son.[1]

Ratcliff was found guilty of premeditated murder and sentenced to death by hanging. The original execution date was August 1895. However, according to the trial transcript, his attorney Vinton Garrett Holliday (1843–1909), a Republican judge in Fairplay, sought a re-trial on the grounds that the jury had been given erroneous instructions. A second trial was held in January 1896, and another guilty verdict was rendered. The Colorado Supreme Court upheld the sentence. Governor Albert McIntire rejected a last-minute appeal after Holliday asserted again that his client was insane. Ratcliff was hence hanged at the Colorado State Penitentiary at Cañon City.[6] Ratcliff was hanged by a weight-and-pulley system that jerked the convicted criminal upwards and instantly broke his neck. Therefore, Ratcliff did not strangle slowly while hanging on a rope in what is known as the drop gallows system.[12]

Among inmates at the time Ratcliff was in the Colorado penitentiary awaiting trial and execution, along with Anton Woode (1882–1950), who at the age of twelve in 1893, was the youngest person in the nation confined to a state institution, convicted of murder and theft,[13] and Alfred Packer, who served nineteen years of a 41-year sentence for killing and cannibalizing five men on a prospecting expedition from Utah into Colorado.[14]

Aftermath

Mrs. Ratcliff and her infant child are interred at Bordenville Cemetery in the now ghost town of Bordenville near Jefferson in Park County.[15] There is no public record regarding Ratcliff's burial. His body lay in the prison coffin for two snowy days in Buena Vista before it was claimed[16] and presumably buried in frozen ground, possibly on his homestead about a mile from the actual domicile.[6]

After Ratcliff's arrest, conviction, and execution, his children inherited nothing under the Homestead Act of 1862 because all were still under the age of twenty-one. The Ratcliff children soon left Park County in April 1896.[17]

The former Ratcliff homestead is located in the Pike National Forest with a view of South Park and surrounding mountains. The physical remains are a two-room structure without a roof or windows. Hidden from public view and easy access, the lot is covered with grass and wildflowers and has a stream of cool, clear water.[6]

There is a two-foot granite obelisk on the former Ratcliff property. It is unknown who erected the obelisk or when it was placed there. In 2010, Ratcliff's descendants placed an engraved paver tile beside the obelisk as a memorial. It is unknown if Ratcliff's grave is at the actual location of the marker.[6]

The Ratcliff case has been termed "the most brutal and unprovoked murder ever known in Park County."[18] On May 9, 1895, the largest funeral procession ever assembled in Park County came together for the last rites of the three victims. After his conviction, Ratcliff claimed that he had given up part of his life wounded in Civil War service and would surrender the remainder of it in the good name of his family.[18]

References

- Transcript of the Triple Murder Trial of Benjamin Ratcliff. Defendant testimony as given on July 18, 1895, Buena Vista, Chaffee County, Colorado

- "1850 Census: Moniteau County, Missouri". Moniteau.net. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- "Elias Ratcliff tombstone". Moniteau.net. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- The Flume, Fairplay, Colorado, July 15, 1880

- Benjamin Ratcliff Enrollment Card information

- Laura King Van Dusen, "Benjamin Ratcliff: Park County Pioneer, Civil War Veteran, Triple Murderer; What Happened and Why", Historic Tales from Park County: Parked in the Past (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2013), ISBN 978-1-62619-161-7, pp. 127-134.

- Missouri Weekly Patriot newspaper, Springfield, Missouri, December 23, 1869

- "Ratcliff-McNair marriage". Moniteau.net. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- "Rob Carrigan, Gottlieb Fluhmann's ghost and Ratcliff side of the story, October 27, 2012". trilakestribune.net. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- The Flume, October 4, 1883; September 8, 1892

- "Ratcliff Found Guilty: The Jury Returned a Verdict Saturday Night". Colorado Springs Gazette. July 27, 1895. p. 1. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- "Diana Andersen, Capital Punishment". ccpl.lib.co.us. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- "Diana Andersen, "Anton Woode"". ccpl.lib.co.us. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- "Diana Andersen, "Alfred Packer"". ccpl.lib.co.us. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- "Bordenville". ghosttowns.com. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- Chaffee County Republican, February 12, 1896

- The Flume, July 9, 1897

- Richard C. Barth, Pioneers of the Colorado Parks. Caxton Press. 1997. p. 254. ISBN 978-0870043819. Retrieved January 25, 2014.