Beachy Head (poem)

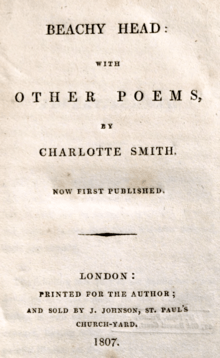

Beachy Head is a long blank verse poem by Charlotte Turner Smith, first published in 1807 as part of the volume Beachy Head and Other Poems. The poem imagines events at the coastal cliffs of Beachy Head from across England's history, to meditate on what Smith saw as the modern corruption caused by commerce and nationalism. It was her last poetic work, published posthumously, and has been described as her most poetically ambitious work.[1] As a Romantic poem, it is notable for its naturalist rather than sublime presentation of the natural world.[1][2][3][4]

| by Charlotte Turner Smith | |

Title page of the first edition | |

| Written | 1806 |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Meter | iambic pentameter |

| Rhyme scheme | blank verse |

| Publication date | January 1807 |

| Lines | 742 |

Composition

Smith began writing Beachy Head in 1803,[5] the same year that England and France ended their one year of peace between the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. At this time, Smith lived in cheap housing near Beachy Head, in poverty due to debt caused by her estranged husband, Benjamin Smith.[6] Her novels had stopped selling well as readers were less sympathetic to her revolutionary political views, and she sold her personal library of 500 books to support herself.[7] She was also increasingly ill during these years, with rheumatoid arthritis making it difficult to write, and sometimes immobilizing her.[7]

Smith continued to write and revise Beachy Head for the next three years.[5] She also wrote extensive footnotes to the poem.[8] She sent a draft of the poem and notes to her publisher Joseph Johnson in May 1806.[9] Smith died on October 28, 1807, and her relatives took over the task of publishing her works.[9] According to the preface, the publication of Beachy Head was delayed because the publisher wanted to locate a preface possibly written by Smith, and to add a biography of her life, but ultimately it was published without these materials.[9] The poem finally appeared in print January 31, 1807, as the first poem of the volume Beachy Head and Other Poems.[9]

The preface written by Smith's publisher states that the poem was "not completed according to the original design," though Smith's last letter to Johnson does not mention intended revisions to the poem other than footnotes.[1] Some scholars have concluded that Smith intended to add a short epitaph to the end of the poem.[10] Others, however, believe that the poem intentionally falls within the genre of the Romantic fragment poem.[11] In this reading, it has been suggested that the incomplete elements are the missing memoir or preface.[1]

Poem

.jpg)

Synopsis

The poem does not present a narrative, but rather a loose meditation on the history of England and humanity's relationship with nature, addressed in an extended apostrophe to the "muse" of Beachy Head. Throughout the poem, the speaker imagines or remembers Beachy Head while regretting being separated from it. The first two stanzas imagine the events of a single day, beginning with dawn on the coast and the departure of fishing boats. A departing merchant ship prompts the speaker to criticize consumerism of luxury goods. The sun sets, the fishing boats return, and smugglers use the coast in darkness. In the third stanza, the poem shifts back in time to describe the history of Beachy Head during the Norman conquest.

The sixth stanza returns to the present day, beginning an extended pastoral section. The poem describes a shepherd, deviating from typical pastoral poetry by demonstrating the rough and laborious realities of peasant life, rather than presenting idealized conventions. The poem describes two village children, whose innocence allows them happiness which the speaker compares to her own lost idyllic childhood. In the eighth stanza, the poem moves to look down upon the roofs of houses in the village, the church, and gardens, describing the bountiful local plants.

The eleventh stanza introduces natural history with the memory of a fossilized seashell found at the top of a cliff. This begins a sequence discussing the limits of science and ambition. The speaker describes how the successive wars fought in the area have not led to lasting glory for the combatants, but have been forgotten. The thirteenth stanza turns away from the futility of war to the more attractive image of the contemporary shepherd, and an imaginary long-distance view of peaceful life in England.

The fifteenth stanza begins a story of a "stranger" who used to live in a ruined castle, wandering and singing. Two fragments of his songs are included, by which he is remembered. He seems to remind the poem's speaker of another solitary but enviable figure, a hermit who lived at the base of the cliffs at Beachy Head. In the nineteenth blank verse stanza, the poem introduces a hermit, who lived a harsh life of exile, but demonstrated virtue by risking his life to rescue sailors from shipwrecks during storms, burying those he could not save. After a particularly terrible storm, the hermit was himself found drowned, and he was buried by shepherds.

The poem ends with the statement that "Those who read / Chisel'd within the rock, these mournful lines, / Memorials of his sufferings, did not grieve," but unlike with the stranger's songs, no "mournful lines" are included in the poem. Some have interpreted these lines to indicate that Smith intended to add more verses to the poem,[10] while others consider the poem to be complete.[11]

Style

Poetic form

The poem consists of 742 lines, in twenty-one blank verse stanzas of varying lengths, with two inserted rhyming poems that add nineteen additional stanzas.[12] It is accompanied by sixty-four footnotes written by Smith.[12]

Unlike Smith's most famous poems, her Elegiac Sonnets, Beachy Head does not follow a strict poetic convention or fall into a clear genre. In one scholar's words, the poem "forgoes the sonnets’ crisp circumspection for expansive blank verse paragraphs."[13] Donelle Ruwe describes the resulting genre as "a greater romantic lyric fragment"[12], and others have also interpreted the poem as an intentional literary fragment.[11][14] The poem combines elements of epic, pastoral, and georgic poetry.[1] It is also often considered a "prospect poem," a popular Romantic genre of poem which presents, and often praises, an external landscape.[15] For these scholars, Beachy Head is "in the first instance a place-related poem, a poem which both describes and constructs place, inscribing it into the imagination of its readers and into cultural history."[16] In this reading, the poem's blank verse paragraphs are often seen as physically resembling the cliffs themselves, akin to concrete poetry.[17]

Poetic speaker

The first half of the poem is narrated from a first-person perspective.[3] Although the speaker is never named, the narrating style is arguably similar to that which is used in the footnotes, suggesting it could be interpreted as Smith herself.[5] The speaker looks at the events at Beachy Head in several perspectives.[5] Some scholars emphasize the omniscience of the speaker, transcending human perspectives,[18][19] while others see limits to what the speaker is able to describe[6] or examine the speaker's individual personality as a person of sensibility.[20] Although the speaker mentions having previously been present at Beachy Head, the poem is entirely imagined, narrated as a hypothetical vision of what the speaker might see if they could revisit the landscape.

Apostrophe and personification

The poem uses apostrophe throughout to address the subjects it describes, including personified concepts like ambition. The opening apostrophe to the cliffs of Beachy Head is similar to the poetic invocation of a muse common in epic poetry. As the speaker continues to address Beachy Head, it develops a personality within the poem that changes it from a backdrop to almost a character in its own right.[21] Ultimately, Beachy Head is presented "not as an instrument to be exploited and gawked at for sentimentalism's sake, but as a 'lively' companion to be sympathized with and regarded on its own plane of being."[21]

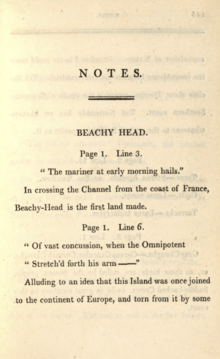

Smith's notes

Smith composed sixty-four notes to accompany the poem,[12] which appeared collected as endnotes in the first edition.[22] These notes provide, among other details, scientific names for plants and animals; descriptions of historical events; and explanations for some of her allusions to other writers. The notes are generally considered an important part of Smith's overall poetic approach.[8][23][15] The notes establish Smith's position as an authority in areas ranging from historical contexts, to geological insights, and scientific examinations of wildlife.[23] Smith's invocation of herself as an expert has been considered particularly impressive since these notes were composed after she sold her personal library, and thus the many facts and quotations included are based solely on her own memory; some quotations are, as a result, not word-perfect, but in general Smith's notes are remarkably accurate. By introducing academic topics, the notes also extend the boundaries of poetry, tying science to poetry in a symbiotic relationship.[8] The combination of approaches mirrors the poem's presentation of the cliff itself as, in one scholar's words, "complex, many-layered, unfinished, and caught up in a continuous process of becoming,"[8] by describing the landscape in multiple ways simultaneously.[8]

Background

Threats of French invasion

England and France were at war from 1792 to 1802 in the French Revolutionary Wars, and after a brief period of peace, returned to war in 1803 with the Napoleonic Wars.[6] By 1805, tensions between the British and French were at their highest pitch, and many Britons feared an imminent invasion by the French.[6] Beachy Head was considered a likely beachhead for the anticipated French invasion of England,[24] and British soldiers were stationed at Beachy Head as part of the British countermeasures.[6] The 1690 Battle of Beachy Head, in which the English navy was defeated by the French, was often discussed in eighteenth century histories of invasion.[25] Beachy Head as a location, therefore, called France to mind as a threat.[26]

Smith has been called a "French Revolution poet,”[6] and frequently wrote in response to the political discourse, events, and philosophy of France.[27][28] Smith supported French revolutionary ideals, especially ideals of radical cosmopolitanism and egalitarianism.[27] In Beachy Head, Smith is "figuratively always looking across the Channel"[20] at France. Beachy Head was chosen as a subject in part because "Smith imagined England as divided from the Continent most thinly by the Channel at this very spot."[29] Smith drew attention to this closeness with her first footnote in the poem,[29] which points out: "In crossing the Channel, from the coast of France, Beachy-Head is the first land made."[22] The poem further highlights the context of the invasion threats by describing the 1690 Battle of Beachy Head, as well as the much earlier successive invasions of England: the Roman conquest of Britain beginning 48 AD, the Danish conquest of England beginning 1015 AD, and the Norman conquest in 1066, which are all imagined to have happened in the same spot.[30] Smith therefore put her contemporaries' “watchful apprehension of what lay beyond the Channel coast"[31] into a broader historical context.[32]

Romanticism

Smith's first published work, Elegiac Sonnets (1784), had been an influential early text in the literary movement which would come to be known as Romanticism.[25] Smith's sonnets differed from previous sonnets in both subject matter and tone.[33] Smith wrote about her personal troubles, rather than love, and created an overall feeling of bleak sadness.[25] She also used less complex rhyme schemes, to write sonnets that were sometimes criticized for their simplicity[34] but have also been seen as pursuing more natural, more direct poetic language which matched the emotions she expressed better than the artificial language common to Italian sonnets.[35] This pursuit of simple, direct expression is among the reasons Smith is classed as a Romantic poet, and partly inspired the poetic innovations of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Lyrical Ballads (1798).[36]

Major themes

Naturalist approach to nature

.jpg)

Like other Romantic poets, Smith considered the natural world to be of great importance, and nature plays a major role in her poetry. Unlike other Romantics, however, Smith's presentation of nature does not attempt to transcend, transform, abstract, or absorb the natural world.[37][38] As such, the poem's presentation of nature has been discussed as providing a contrast to other Romantic poetry, especially that of William Wordsworth[2][3][4] or Percy Shelley's Mont Blanc.[1]

One distinctive element of Smith's treatment of nature is her attention to scientific accuracy. Beachy Head is noted for its "microscopic"[1] attention to the detailed reality of plants and fossils, embracing natural history as the means through which to understand nature.[3][4] Smith's interest in botany and ornithology is reflected in her footnotes describing the scientific names of fifty-one species of birds and plants.[39] The botanical accuracy of Smith's poems was a hallmark of her writing from her first book, Elegiac Sonnets, which the later poet John Clare praised "because she wrote more from what she had seen of nature then [sic] from what she had read of it."[40] Smith's eagerness to understand and describe the details of the natural world scientifically is contrasted with the "infinite, unthinkable"[1] scope of nature in poems like The Prelude and Mont Blanc.[1][3][4]

Smith's approach to nature is also distinct for showing human activity as an integral part of the natural world, and embracing human stewardship of land and animals, which as been described as representing a "social ecology."[41] Literary scholars interested in ecocriticism have described Smith as "one of the first social ecologist poets."[42] Beachy Head is seen as calling for a more sustainable, more intimate relationship with nature, rather than treating the natural world as a resource to be exploited. In this way, Smith no longer seems to contrast with other Romantic attitudes toward nature. Instead, her interest in scientific minutiae is seen as a way of expanding the "green language" of Romanticism itself.[29] The concept of "green language" was defined in Raymond Williams's 1973 monograph The Country and the City as a new way of writing about nature exemplified by William Wordsworth and John Clare, which combines "a deep sensitivity for natural phenomena with forceful environmental advocacy."[43] Smith's "green language," according to Donna Landry, is "botanically exact and scientific yet charged with feeling," accomplishing the same goals with different rhetoric.[44]

Pastoral critique of commerce

Pastoral poetry conventionally presents the rural poor as innocent and carefree, in contrast with corrupt and unhappy urban dwellers. Often, this contrast also involves an unrealistically idealized image of daily life in rural communities. Smith's depiction of rural life and multiple shepherd characters both evokes and subverts the traditional pastoral mode.[14] In keeping with common pastoral themes, Smith ennobles the hardships of the rural poor, and criticizes the luxuries of the rich.[45] Smith juxtaposes pastoral happiness with the history of commerce as a way of revealing the unethical and exploitative nature of trade, which is harmful both to humanity and to nature.[46] She especially criticizes the phenomenon of shepherds and farmers abandoning rural labor in favour of smuggling, now that war with France has increased the demand for smuggled goods.[47] The poem thus eulogizes "the erstwhile happiness of agrarian and peasant life," a classic pastoral subject.[24]

However, Smith is also realistic about the daily hard work required for rural life.[14] She explores "the Petrarchan oxymoron of un-pastoral shepherds," with a shepherd character who is "neither the passive, suffering observer nor the pastoral fantasy of innocence."[11] Smith also draws a contrast between real shepherds, who "toil with the realities of poverty, demeaning labor, and savage familial relationships," and the character of the "wanderer" who writes poetry about how he imagines his life would be better if he were a shepherd.[48] His ideal images are undermined by juxtaposition with the many real rural labourers who view him with suspicion.[48] As such, although she rejects urban vices and commerce, and sees a form of freedom in the independence possible in rural isolation, Smith also intentionally depicts the oppression caused by wealth inequality, and rejects "the myth of the happy laborer who needs only to work the English countryside to be content."[48]

Human history and geological time

The poem has been described as a dialectical exploration of historiography, placing local personal histories alongside grand national narratives of history.[24] Scholars also draw attention to its relation to the ongoing history being made of the Napoleonic war, and Smith's support of revolutionary efforts in America and France.[1][49] Whereas other Romantic poets, especially Wordsworth, typically respond to significant changes in their society by creating a poetic world which does not include them, Smith's poetry is a "combination of imaginative verse and historical discourse, that refuses to cleanse the poetical vision of the oppression evident all around her."[50] The poem expresses intertwined personal and political turmoil,[1] combining what literary critic Donelle Ruwe describes as "the apocalyptic war rhetoric of the romantic era, as well as ... the celebration of the quotidian."[39]

Also in tension with these personal and national human histories is the sense of a far older geological history. In its frequent descriptions of the stone, the earth, fossilized remains, and buried human remains, the poem is "threaded through by conceptions of a deep earth, of deep time."[19] The theory of plate tectonics would not become widely-accepted for more than a hundred years, but Smith's poem observes evidence of geological change in the presence of fossils on mountaintops and similarities between the French and English shores. Her footnotes mention Nicolas Desmarest's 1751 theory that France and Great Britain were formerly joined by a land bridge, which was broken by some sort of "revolution" in the Earth itself. Smith links Desmarest's geological "revolution" to the ongoing political revolutions in Europe, placing them on a long and ongoing timescale whose ultimate results are impossible to imagine while they are ongoing.[6] However, she does not consider Desmarest's theory, or any other geological theories, such as neptunism and plutonism fully satisfactory explanations, since they ignored fossil evidence.[51] The geological and archeological findings revealed by the hills of Beachy Head serve to highlight the limitations of human pride and scientific accomplishment.[14]

Nostalgia and melancholia

Smith grew up in the countryside and came to know the land quite well. As a result, the poem Beachy Head:

...expresses her nostalgia and longing for the sense of freedom and unity of being that she associates with this childhood landscape, as well as her continued love for the many manifestations of life there that she has always taken delight in and observed so closely. This evocation of place, then, is very much bound up with the poet's own life, encompassing memories of childhood as well as mature reflection upon those memories and an expanded sense of vastness and complexity of life, social and natural, viewed from this vantage point, this “rock sublime.”[52]

In terms of melancholia, Hunt points out, “Beachy Head presents melancholia in a much more abstract sense, musing on the state of the world, time and mankind's sorrows from atop the Sussex cliffs”.[53] These cliffs provide a powerful position from which to express melancholia, considering Beachy Head is well-known for suicide.

The hermit

The character of the hermit, named Darby, appears at the end of the poem who rescues sailors from shipwrecks near the cliffs of Beachy Head. The hermit appears as a sort of “symbolic figure”[54] who has seen “the ‘crimes’ on both sides of the Channel, and become ‘outraged’ but has survived as a moral representative of the highest ideals of the person of sensibility”.[54] “While characterized as “not indeed unhappy”(1.656) by the narrator, this poet-figure is nevertheless criticized for being egocentric and unproductive, and stands in marked contrast to a second hermit figure who has fled the world…because he was “long disgusted with the world/ And all its ways” (2.673-4) in general”.[55] Smith’s notes indicate that the hermit had never had a home other than the cave under the cliff, and survived “almost entirely on shell-fish”.[56] These notes also indicate that Darby was a sort of folk tale to the people of the country, and that Smith herself of a “parson Darby”[56] some thirty years before the note was written. Near the end of the tale, the hermit leaves on a “charitable mission during a violent equinoctial storm”[56] and sadly perishes, whereupon some local shepherds seek out his cave only to find it empty, and later find his corpse washed up near his former dwelling. The shepherds bury the body, and Darby receives the “rites of burial”.[56] The poem promises to provide an epitaph for the hermit, “Chisel’d within the rock, these mournful lines, / Memorials of his sufferings”,[56] but then ends abruptly without it; critics are undecided whether the poem was unfinished because Smith died before it was complete, or whether the ending was intentionally left unwritten. Interestingly, Beachy Head does not appear to be the only poem in which Smith features the character of the hermit; in her poem "Sonnet: On Being Cautioned Against Walking on an Headland Overlooking the Sea, Because It Was Frequented by a Lunatic" the character of the hermit is similarly used as a figure who has been totally isolated from the world around him, more envious of the world around him than afraid of it.[57]

Kari Lokke writes in “The Figure of the Hermit in Charlotte Smith’s Beachy Head”:

Twenty years before Beachy Head, we find in Mary Wollstonecraft's “Cave of Fancy” a strange and suggestive precursor to Smith's hermit in the figure of the seaside recluse Sagestus. In this gothic morality tale, a fragment begun in 1787, published posthumously in 1798, Wollstonecraft, like Smith, sets her hermit against a backdrop of disillusionment and mutability.[58]

Lokke continues:

Beachy Head moves spectacularly from a sweeping and panoramic cosmological, geographical, and historical vision, to a regional portrait of the Sussex Downs, to a series of village vignettes, before concluding with the single and isolated figure of "the lone Hermit"[59] in the final lines of the poem.[58]

The figure of the hermit in Beachy Head represents an interpretative problem in the poem as a whole. The figure provides an insight into Smith’s moral, spiritual, and aesthetic project within the poem. The conclusion of the poem represents the poem as a whole, with language like “these mournful lines,” “Chisel’d within the rock”,[59] being dedicated to the Hermits “Memorials of his sufferings” (728), quite possibly written by him himself before his death. In a way, the Hermit buried at the bottom of the cliff constitutes Smith’s response to the opening of the poem, then the figure of the Hermit completes the poem by answering the sublime prospect with a refusal of the distance and detachment necessary for the masculine sublime, and with a re-inscription of the human into the natural.[58] According to Lokke, Smith's hermit is a being of compassion, even mercy:

“...an embodiment of absolute compassion, outside of space and time. His feeling is an active compassion that seeks expression in a particular historical and phenomenal moment and that abandons the distance and physical safety upon which the masculine sublime aesthetic response is predicated.”[58]

Furthermore, Lokke writes, “The altruism and usefulness of the final Hermit figure in Beachy Head thus challenge the self-absorption of the solitary poet recluse who precedes him in the poem.”[58]

One cannot know whether Charlotte Smith intended to conclude Beachy Head with the figure of the hermit or, as Stuart Curran writes, "whether her masterpiece. . . was as unfinished as the introductory note to the volume assumes it to be."[58]

The sublime

.jpg)

Modern feminist critics have emphasized Beachy Head’s shift toward the anti-sublime;[60] however according to Kelley, this reading was propped up by Burkean aesthetics and supposes that a sublime viewpoint is male and god-like in its capacities, whereas a picturesque or beautiful perspective is lower, more involved, more shaped to the look of the land and its particulars. The aesthetics of particularity, whether beautiful or picturesque, might seem to offer a way for history or narrative to become less grand, more local, and perhaps more true.[60] The fossils’ smallness also might qualify them as ‘‘sublime,’’ since Edmund Burke suggests that ‘‘the wonders of minuteness’’ may be like the wonders of vastness in their effect.[61]

_found_at_the_entrance_of_the_cave_N%C2%B0_2_de_la_Roche_Fouet_-_Coll._J.C.Staigre.jpg)

Most significantly, fossils provoke feelings definitive of the sublime experience, such as wonder and a sense of incomprehension.[61] In Beachy Head specifically, the fossils evoke not only the general range of geological controversies, but with increasing force through these decades, the deepening temporal description of the earth’s history, and the accompanying possibilities for epistemological uncertainty.[61]

Moreover, images of fossil sea-shells are made to provoke aesthetic instabilities which are not merely unresolved, but are actively assisted, by the poem’s larger structures. We must turn our attention, then, to what might be understood as an experiment, a self-reflexive testing of the picturesque and the sublime, and to the questions that experiment raises about the limits of these aesthetics.[61] Wallace continues:

The tiny fossils open into a meditation on the inefficacy of science and history from which cascades an epistemological crisis: if the empirical reasoning which underwrites not only science and history, but picturesque and sublime aesthetics, cannot trace our experiences in the present world back to their material causes, then what will replace that way of knowing.[61]

Influences

Throughout the 1790s, many writers were influenced and inspired by the political atmosphere that arose from the French Revolution.[62] Unlike their male counterparts, many female writers of the time were overlooked or forgotten; however, with re-observation it is evident that female writers were greatly interested in political discourse and events.[62] Adriana Craciun continues this argument in her 2005 book which focuses on French Revolutionary thought and English women writers.[62] She claims, Charlotte Smith, along with other female contemporaries such as Mary Wollstonecraft and Helen Maria Williams were influenced by french philosophers, which further cultivated these women’s personal ideals of radical cosmopolitanism and egalitarianism.[62]

The two individuals who had the most influence on Charlotte Smith's poetry are Erasmus Darwin and William Cowper.[63] Darwin’s poem The Love of the Plants (1789) inspired Smith as well as other female writers to develop their own work, ultimately creating a new sub-genre that challenges a predominantly male dominant scientific field.[64][65] Darwin's influence is further rectified by the use of minutiae throughout Beachy Head.[65] Smith also demonstrates scientific influence through use of linnaean classification and analogy.[66] By applying scientific annotations to her poetry, Smith is able to create her own reality and use scholarly/ informative material to validate her claims.[63] In Watchwords: Romanticism and the Poetics of Attention the author, Gurton-Wachter, suggests that these analogical parallels in Linnaeus’s work, as well as in Darwin and Smith's poetry provide accurate details and insights to the readers[67] Smith’s geological depictions of Beachy Head further demonstrates her literary repertoire as she is versed in Milton's work Paradise Lost; Kevis Goodman acknowledges that Smith similarly echoes lines of Milton's Creation in her poem.[68]

In the article, “Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head: Science and the Dual Affliction of Minute Sympathy,” Kelli M. Holt, demonstrates Smith’s engagement with Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), and Anna Barbauld's 1773 work, An Inquiry into Those Kinds of Distress which Excite Agreeable Sensations. Charlotte Smith stresses the gendered politics of compassion, sympathy, and reason in favour of her predecessors gendered opposing ideologies creating a juxtaposition; this is done with reference to Baurbalds opinion on the distress of others, and Adam Smith’s argument of a masculine reasoned based sympathy.[65]

William Wordsworth is another famous contemporary who valued Smith’s poetry himself, Judith Stanton critiques in her article; “if anything, [Wordsworth's] approach and style is Smithian”.[69] As discussed in Jacqueline Labbe’s book, Charlotte Smith: Romanticism, Poetry, and the Culture of Gender, Wordsworth and Smith develop reciprocated approaches to their poetry in regards to themes, subject, and speaker; for example Smith alludes to Wordsworth's writing in Beachy Head through the hermit character, whose actions, qualities and lines shares many similarities of Wordsworth's speakers and subjects.[70]

Reception

Although Charlotte Smith’s influence has been “profound and long-lasting",[71] her work has been underrepresented in the study of Romantic literature.[72][73] In the essay “Romantic Histories: Charlotte Smith and Beachy Head,” Theresa M. Kelley notes that Smith’s work remained largely unexplored in the twentieth century until the 1980s when “scholars began to circulate unpublished transcripts of her poems”.[73]

Academic Stephen C. Behrendt notes that while Smith’s influence was “wide, formative, and powerful,” few of her contemporaries left detailed accounts of her influence on their work.[74] Despite this, her influence was understood by her contemporaries.[71] An 1807 review of Beachy Head: With Other Poems in the Annual Review and History of Literature notes that “as a descriptive writer, either in verse or prose, she [Smith] was surpassed by few[75]” while an 1808 review of Beachy Head in British Critic acknowledges Smith as a “genuine child of genius” and notes that her “poetic feeling and ability have rarely been surpassed by any individual of her sex”.[76]

Although some contemporary critics claim Smith’s work has a tendency to “read stiltedly” for modern audiences,[77] Jacqueline M. Labbe contends that Smith’s work, including Beachy Head, calls to the “Romantic notion of individuality” but that it does so in a way that is “inflected by a desire to challenge social constructions of individuality”.[78] Stuart Curran, editor of The Poems of Charlotte Smith, argues that Beachy Head is a work that “strikes distinctly modern chords” from both a psychological and ecological standpoint.[79]

19th century

During her lifetime, Charlotte Smith was recognized as an influential British Romantic writer for her influential and famous Elegiac Sonnets – these poems sparked a revival for the sonnet form, which was adopted by other Romantics including William Wordsworth, John Keats, Percy Shelley, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.[80]

Early reception of Beachy Head was largely positive. In 1807, an unnamed British Critic reviewer described it, and her other posthumously published poetry, as “some of her best work."[81]

Smith’s death and gender both played a role in defining early reception of Beachy Head. In the review by the unnamed British Critic, he lamented her death and described her genius as “rarely… surpassed by any individual of her sex."[81] The Critic quotes Beachy Head’s long passage of personal lament. At the same time, a sonnet published in The Times in April 1807 titled “the Exile --- A Sonnet Attempted in the Style of the Late Mrs. Charlotte Smith,” creates a combination of Smith as the poet of Elegiac Sonnets and as the poor wanderer of Beachy Head. According to Theresa Kelley, “the Times sonnet memorializes Smith as a dead speaker… precisely the kind of elegiac gesture that she had earlier trained her readers to make.[82]

Later, in 1825, Alexander Dyce published Specimens of British Poetesses: Selected and Chronologically Arranged in which he wrote that Charlotte Smith’s Beachy Head had “fresh and vivid” descriptions of rural scenery.[83] Dyce also explained that Smith’s love of botany allowed her to “paint a variety of flowers with a minuteness and a delicacy rarely equaled”.[83]

Otherwise, there exists little critical response to Beachy Head from the time of its initial publication. Critical focus tended to be upon her earlier works, particularly her Elegiac Sonnets, The Emigrants, and Emmeline.

20th and 21st centuries

For much of the early 20th Century, Beachy Head continued to exist in relative obscurity, especially in comparison to her other works. Towards the latter half of the 20th Century, however, that Beachy Head would begin its explosive critical resurgence. Myriad interpretations and critiques quickly started emerging between 1970 and 2000. There has been what some call a “literary renaissance” for women writers; in the past, scholarly studies as well as mainstream interests in Romantic literature have often overlooked works by female writers.[60] Charlotte Smith, despite her relative fame during her lifetime, was no exception. Literature scholars in the 1980s studied and printed unpublished manuscripts and collections of poems from female writers, thus making them accessible to a modern group of readers.[60]

In 1997, Donelle R. Ruwe referred to Beachy Head as a synthesis of “literature, botanical science, and Erasmus Darwin’s The Botanic Garden.[84] For Ruwe, however, Beachy Head’s importance came largely from its context in Smith’s larger body of work regarding nature. This way of seeing Beachy Head will go on to be referred to as a ‘dependent fragment poem.’ Critic John Anderson argues that Beachy Head was the first in line of ‘dependent fragment poems’[85] He explains that a dependent fragment poem as “The formal determinacy of such poems depends on the readers propensity to relate the fragment to relevant precursors or successors in the authors canon”.[59] Anderson then argues that Keates is the latest of these poets while Smith is the earliest. Similarly, Keates two fragmented epics, “Beachy Head is a fragment that must be fitted into its authors other poetry, that is, “dependant” as a keystone would be”.[59]

For other modern critics, gender is a key feature of Beachy Head. Theresa M. Kelley argues that the role of gender in Beachy Head is very different from, “...the highly feminized rhetoric of Smith’s earlier poems and so many of her letters.”[60] Kelley further explains that Smith’s poem asks readers to consider gender not so much as the work of an autobiographical,” female poet-speaker who uses an elegiac voice to dun her readers, insisting on their sympathy whether they will or no, but as work concerned with the elegiac as a condition of history (human and geological) that bites into the task of narrating stories of all kinds.”[60] She explains that the elegiac subject of Beachy Head is not centrally the woman poet attacked by others, but that the writing of history is difficult when records are in disagreement with each other.[60] As an outsider to ‘real’ history and ‘real’ literature practiced by men, Smith inevitably experienced gender as “a figure for incompletion, for disrupted and partial narrative.”[60] Kelley also examines the work of those critics who came before her in “Romantic Histories: Charlotte Smith and ‘Beachy Head." She asserts that Judith Pascoe, Donelle Ruwe, and Donna K. Landry, “all link the poem’s botanical apparatus to women’s writing on botany and pedagogy during the period.”[60] Pascoe and Ruwe also argue that Smith’s botanical knowledge within the poem as well as the footnotes “amounts to a manifesto of intellectual capability.”[86]

According to Jacqueline M Labbe, Beachy Head is in some ways an attempt to engage with her male contemporary William Wordsworth; in Beachy Head, Smith refers to several of his poems, such as Tintern Abbey, in a convoluted and constrained way although it is likely that Smith was relying on the knowledge her readership of his work to draw parallels.[86] Labbe argues that Smith’s objective is to challenge Wordsworth’s constructed “hierarchy of perception” by offering her own vivid descriptions of a vast spectrum of sensations while also drawing attention to his appropriation of her stylistic use of imagery, particularly in his works from 1798.[86] With this additional layer of Beachy Head, Smith effectively buries Wordsworth within the limestone along with the fossils, botany, geology, politics, war, national as well as her own personal history as a female poet.[86] Labbe concludes that the speaker in Beachy Head rejects history, society and culture as they move from the headland, through the layers of limestone, only to end at the foot of the clift adopting the life of the Hermit.[86]

Adaptations

Beachy Head has been adapted to music by composer Amanda Jacobs and scholar Elizabeth A. Dolan as “The Song Cycles of Beachy Head.” The Song Cycles are written for a mezzo soprano voice and adapt lines directly from the poem, shaping them into lyrical form, making a product of both music and literature. The Song Cycles consist of 26 songs, which can be broken up into five interdependent song cycles, played separately or together. The project was composed after Jacobs and Dolan met at Chawton House in Hampshire, England, and took two years to complete. In 2017, “The Song Cycles of Beachy Head” were recorded live at the debut in Melbourne, Australia with Dolan as lecturer, Jacobs on piano, and Shelley Waite as mezzo soprano. The debut was attended by Melbourne-based descendants of Charlotte Smith through her son, Nicholas Hankey, and has since been performed through concerts in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.[87]

Notes

- Singer 2012.

- Tayebi 2004.

- Wallace 2002.

- Ruwe 1999.

- Keane 2012.

- Goodman 2014.

- Blank 2003.

- Erchinger 2018.

- Knowles 2017.

- Fletcher 1998.

- Anderson 2000.

- Ruwe 2016.

- Zimmerman 2007, p. 492.

- Lokke 2008.

- Labbe 2017.

- Radu 2017, p. 443.

- Morton 2014, p. 272.

- Black 2018.

- Wallace 2019.

- Backscheider 2005.

- Holt 2014.

- Smith 1807.

- Heringman 2004.

- Kelley 2004.

- Knowles & Horrocks 2017.

- Gurton‐Wachter 2009.

- Craciun 2005.

- Schabert 2014.

- Landry 2000.

- Goodman 2014, p. 988.

- Goodman 2014, p. 984.

- Goodman 2014, p. 989.

- Feldman & Robinson 1999.

- Feldman & Robinson 1999, p. 12.

- Feldman & Robinson 1999, p. 11.

- Black et al. 2010.

- Pascoe 1994, p. 203-204.

- Curran 1993, p. xxviii.

- Ruwe 2016, p. 300.

- Landry 2000, p. 488.

- Landry 2000, p. 487.

- Holt 2014, p. 1.

- McKusick 1991.

- Landry 2000, p. 489.

- Landry 2000, p. 483.

- Haekel 2017.

- Tayebi 2004, p. 135.

- Tayebi 2004, p. 137.

- Bray 1993.

- Tayebi 2004, p. 131.

- Heringman 2004, p. 276.

- Shelley, Julia Catherine. “The Aesthetic Politics of Landscape in the Poetry of Charlotte Smith.” pp 41-72, 1992.

- Hunt, Olly. “Melancholia in Charlotte Smith’s Verse.” Online Journal of Literary Criticism and Creativity, issue 3, 16 November 2012.

- Backscheider, Paula R. (2005). Eighteenth Century Women Poets and their Poetry: Inventing Agency, Inventing Genre. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Reinfandt, Christopher (2013). Proceedings. Röder, Katrin,, Wischer, Ilse, 1959-. Trier: WVT, Wiss. Verl. Trier. pp. 99–114. ISBN 978-3-86821-488-8. OCLC 862807510.

- The Broadview anthology of British literature. Black, Joseph, 1962-, Conolly, L. W. (Leonard W.),, Flint, Kate,, Grundy, Isobel,, LePan, Don, 1954-, Liuzza, R. M. (Third ed.). Peterborough, Ontario, Canada. 2014-12-04. ISBN 978-1-55481-202-8. OCLC 894141161.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The Longman anthology of poetry. McMahon, Lynne., Curdy, Averill. New York: Pearson/Longman. 2006. ISBN 0-321-11725-5. OCLC 55124911.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Lokke, Karri (2008). "The Figure of the Hermit in Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head". The Wordsworth Circle. 39 (1–2): 38–43. doi:10.1086/TWC24045185.

- Burroughs, Catherine (2003). "The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama. Ed. Jeffrey N. Cox and Michael Gamer. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2003. ISBN 1551112981. Price: $44.95 (US$29.95)". Romanticism on the Net (29–30). doi:10.7202/007728ar. ISSN 1467-1255.

- Kelley, Theresa (2004). "Romantic Histories". Nineteenth-Century Literature. 59 (3): 281–314. doi:10.1525/ncl.2004.59.3.281.

- Wallace, Anne (2019). "Interfusing Living and Nonliving in Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head". The Wordsworth Circle. 50: 1–19. doi:10.1086/702580.

- Schabert, Ina (October 2014). "From Feminist to Integrationist Literary History: 18th Century Studies 2005-2013: From Feminist to Integrationist History". Literature Compass. 11 (10): 667–676. doi:10.1111/lic3.12179.

- Curran, Stuart (1994). "Charlotte Smith and British Romanticism". South Central Review. 11 (2): 66–78. doi:10.2307/3189989. ISSN 0743-6831. JSTOR 3189989.

- Scarth, Kate (2014-08-05). "Elite Metropolitan Culture, Women, and Greater London in Charlotte Smith's Emmeline and Celestina". European Romantic Review. 25 (5): 627–648. doi:10.1080/10509585.2014.938230. ISSN 1050-9585.

- Holt, Kelly M. "Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head: Science and the Dual Affliction of Minute Sympathy". ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts 1640-1830. 4: 2014.

- Gurton-Wachter, Lily (2016-03-23). Watchwords. Stanford University Press. doi:10.11126/stanford/9780804796958.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-8047-9695-8.

- Powell, Rosalind (2016). "Linnaeus, Analogy, and Taxonomy: Botanical Naming and Categorization in Erasmus Darwin and Charlotte Smith". Philological Quarterly. 95: 101–124. S2CID 164047106.

- Goodman, Kevis (2014). "Conjectures on Beachy Head: Charlotte Smith's Geological Poetics and the Ground of the Present". ELH. 81 (3): 983–1006. doi:10.1353/elh.2014.0033. ISSN 1080-6547.

- Stanton, Judith (2006). "Review of Charlotte Smith: Romanticism, Poetry, and the Culture of Gender". Keats-Shelley Journal. 55: 246–248. ISSN 0453-4387. JSTOR 30210660.

- Labbe, Jacqueline M. (2011). Charlotte Smith Romanticism, poetry and the culture of gender. Manchester University Press. OCLC 935016562.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. (2008). "Charlotte Smith, Women Poets, and the Culture of Celebrity". In Labbe, Jacqueline (ed.). Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. Labbe, Pickering & Chatto. pp. 189.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. (2008). "Charlotte Smith, Women Poets, and the Culture of Celebrity". In Labbe, Jacqueline (ed.). Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. Pickering & Chatto. pp. 189.

- Kelley, Theresa M. (2004). "Romantic Histories: Charlotte Smith and Beachy Head". Nineteenth-Century Literature. 59 (3): 281. doi:10.1525/ncl.2004.59.3.281.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. "Charlotte Smith, Women Poets, and the Culture of Celebrity". In Jacqueline, Labbe (ed.). Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. Pickering & Chatto. p. 201.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. (2008). "Charlotte Smith, Women Poets, and the Culture of Celebrity". In Labbe, Jacqueline (ed.). Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. Labbe. pp. 190–191.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. (2008). "Charlotte Smith, Women Poets, and the Culture of Celebrity". In Labbe, Jacqueline (ed.). Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. Pickering & Chatto. pp. 189–190.

- Blain, Virginia (1990). The Feminist Companion to Literature in English: Women Writers from the Middle Ages to the Present. Yacle University Press. p. 996.

- Labbe, Jacqueline M (2011). Charlotte Smith: Romanticism, Poetry and the Culture of Gender. Manchester University Press. p. 8.

- Smith, Charlotte; Curran, Stuart (1993). The Poems of Charlotte Smith. Oxford University Press. pp. xxvii–xxviii.

- Dolan, Elizabeth. "The Song Cycles of Beachy Head". The Song Cycles of Beachy Head. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

- Critic, British (2003). "Beachy Head With Other Poems". Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism, Edied by Lynn M. Zott. 115: 118 – via Literature Criticism Online.

- Kelley, Theresa (2004). "Romantic Histories: Charlotte Smith & "Beachy Head"". Nineteenth Century Literature. 59. doi:10.1525/ncl.2004.59.3.281.

- Dyce, Alexander (1825). Specimens of British Poetesses: Selected and Chronologically Arranged. T. Rodd. p. 253.

- Ruwe, Donelle (2003). "Benevolent Brothers and Supervising Mothers: Ideology in the Children's Verses of Mary and Charles Lamb and Charlotte Smith". Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism, Edited by Lynn M. Zott. 125: 337 – via Gale Literature Criticism.

- Anderson, John (2000). "Beachy Head: The Romantic Fragment Poem as Mosaic". The Huntington Library Quarterly. 63 (4): 547–VI. doi:10.2307/3817616. JSTOR 3817616.

- Labbe, Jaqueline (2006). "Reviews - Charlotte Smith: Romanticism, Poetry, and the Culture of Gender". Keats-Shelley Journal. 55: 246.

- "The Song Cycles of Beachy Head". wordpress.lehigh.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

References

- Anderson, John M. (2000). ""Beachy Head": The Romantic Fragment Poem As Mosaic". Huntington Library Quarterly. 63 (4): 547–574. doi:10.2307/3817616. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3817616.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Backscheider, Paula R. (2005). Eighteenth Century Women Poets and their Poetry: Inventing Agency, Inventing Genre. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Behrendt, Stephen C. (2008). "Charlotte Smith, Women Poets, and the Culture of Celebrity". In Labbe, Jacqueline (ed.). Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. Pickering & Chatto.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Joseph, ed. (2018). Beachy Head (3 ed.). Broadview Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Joseph; Conolly, Leonard; Flint, Kate; Grundy, Isobel; LePan, Don; Liuzza, Roy; McGann, Jerome J.; Prescott, Anne Lake; Qualls, Barry V.; Waters, Claire, eds. (2010). "Charlotte Smith". The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Age of Romanticism. Volume 4 (Second ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 44–45.

- Blank, Antje (2003-06-23). "Charlotte Smith". The Literary Encyclopedia. 1.2.1.06: English Writing and Culture of the Romantic Period, 1789-1837.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bray, Matthew (1993). "Removing the Ango-Saxon Yoke: The Francocentric Vision of Charlotte Smith's Later Works". Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism. 115: 155–159.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Craciun, Adriana (2005). British Women Writers and the French Revolution: Citizens of the World. Palgrave.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curran, Stuart, ed. (1993). "Introduction". The Poems of Charlotte Smith. New York. pp. xix–xxix.

- Erchinger, Phillip (2018). "Science, Footnotes, and the Margins of Poetry in Percy B. Shelley's Queen Mab and Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head". European Journal of English Studies. 22 (3): 241–257. doi:10.1080/13825577.2018.1513709.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Feldman, Paula R.; Robinson, Daniel (1999). A Century of Sonnets: The Romantic-Era Revival, 1750-1850. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511561-1. OCLC 252607495.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fletcher, Loraine (1998). Charlotte Smith: A Critical Biography. Palgrave.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodman, Kevis (2014). "Conjectures on Beachy Head: Charlotte Smith's Geological poetics and the grounds of the present". ELH. 81 (3): 983–1006. doi:10.1353/elh.2014.0033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gurton‐Wachter, Lily (2009). ""An Enemy, I suppose, that Nature has made": Charlotte Smith and the natural enemy". European Romantic Review. 20 (2): 197–205. doi:10.1080/10509580902840475. ISSN 1050-9585.

- Heringman, Noah (2004). Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holt, Kelly M. (2014). "Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head: Science and the Dual Affliction of Minute Sympathy". ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts 1640-1830. 4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keane, Angela (2012). Revolutionary Women Writers: Charlotte Smith and Helen Maria Williams. Northcote House Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kelley, Theresa (2004). "Romantic Histories: Charlotte Smith and Beachy Head". Nineteenth-Century Literature. 59 (3): 281–314. doi:10.1525/ncl.2004.59.3.281.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knowles, Claire; Horrocks, Ingrid, eds. (2017). Charlotte Smith: Major Poetic Works. Broadview Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Labbe, Jacqueline (2017). "Charlotte Smith, Beachy Head". In Wu, Duncan (ed.). A Companion to Romanticism. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 221–227. ISBN 978-1-4051-6539-6. OCLC 244174741.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Landry, Donna (January 2000). "Green Languages? Women Poets as Naturalists in 1653 and 1807". Huntington Library Quarterly. 63 (4): 467–489. doi:10.2307/3817613. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3817613.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Lokke, Kari (2008). "The Figure of the Hermit in Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head". The Wordsworth Circle. 39 (1–2): 38–43. doi:10.1086/TWC24045185.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKusick, James C. (1991). "'A language that is ever green': The Ecological Vision of John Clare". University of Toronto Quarterly. 61 (2): 226–249. ISSN 1712-5278.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morton, Timothy (2014). Material Ecocriticism. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-253-01395-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pascoe, Judith (1994). "Female Botanists and the Poetry of Charlotte Smith". In Wilson, Carol Shiner; Haefner, Joel (eds.). Re-Visioning Romanticism. University of Philadelphia Press. pp. 193–209.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radu, Anca-Raluca (2017). "Charlotte Smith, Beachy Head (1807)". In Haekel, Ralf (ed.). Handbook of British Romanticism. De Gruyter Inc. p. 443.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ruwe, Donelle (1999). "Charlotte Smith's Sublime: Feminine Poetics, Botany, and Beachy Head". Essays in Romanticism. 7 (1): 117–132. doi:10.3828/EIR.7.1.7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ruwe, Donelle (2016). "Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head and the Lyric Mode". Pedagogy. 16 (2): 300–307. doi:10.1215/15314200-3435916.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schabert, Ina (October 2014). "From Feminist to Integrationist Literary History: 18th Century Studies 2005-2013: From Feminist to Integrationist History". Literature Compass. 11 (10): 667–676. doi:10.1111/lic3.12179.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singer, Katherine (2012-06-23). "Charlotte Smith: Beachy Head". The Literary Encyclopedia. 1.2.1.06: English Writing and Culture of the Romantic Period, 1789-1837.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Charlotte (1807). Beachy Head: With Other Poems. London: J. Johnson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tayebi, Kandi (2004). "Undermining the Eighteenth-Century Pastoral: Rewriting the Poet's Relationship to Nature in Charlotte Smith's Poetry". European Romantic Review. 15 (1): 131–50.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace, Anne D. (2002). "Picturesque Fossils, Sublime Geology? The Crisis of Authority in Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head". European Romantic Review. 12: 77–93.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace, Anne D. (January 2019). "Interfusing Living and Nonliving in Charlotte Smith's "Beachy Head"". The Wordsworth Circle. 50 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1086/702580. ISSN 0043-8006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zimmerman, Sarah (2007). "Varieties of Privacy in Charlotte Smith's Poetry". European Romantic Review. 18 (4): 492. doi:10.1080/10509580701646800.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, John M. (2002). "The Romantic Fragment Poem As Mosaic". In Mellor, Anne K.; Nussbaum, Felicity; F. S. Post, Jonathan (eds.). Forging Connections: Women's Poetry from Renaissance to Romanticism. San Marino: Huntington Library. pp. 119–46.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. “Charlotte Smith, Women Poets, and the Culture of Celebrity.” Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism, edited by Jacqueline Labbe, Pickering & Chatto, 2008, pp. 189–202.

- Blagdon, Francis William. “Biography: Francis William Blagdon on Charlotte Smith.” Flowers of Literature, 1807.https://broadviewpress.com/product/charlotte-smith-the-major-poetic-works/

- Blain, Virginia, et al. The Feminist Companion to Literature in English: Women Writers from the Middle Ages to the Present. Yacle University Press, 1990, pp. 996.

- Smith, Charlotte (1807). Black, Joseph (ed.). Beachy Head (3 ed.). Broadview Press.

- Bray, Matthew. “Removing the Anglo-Saxon Yoke: The Francocentric Vision of Charlotte Smith’s Later Works.” The Wordsworth Circle 23.4 (1993): 155–58.

- Chambers, Robert. “Biography: Robert Chambers on Charlotte Smith.” In Cyclopaedia of English Literature, 1844.

- Craciun, Adriana. (2005). British Women Writers and the French Revolution: Citizens of the World. Palgrave.

- Croley, Allison E. “Counter Pastoralism in Charlotte Smith’s Beachy Head.” The Digital Charlotte Smith. Undergraduate Library Research Award, 2014.

- Erchinger, Philipp. “Science, footnotes, and the margins of poetry in Percy B. Shelley’s Queen Mab and Charlotte Smith’s Beachy Head.” European Journal of English Studies, vol. 22, issue 3, pp. 241–257.

- Fletcher, Loraine. (1998). Charlotte Smith: A Critical Biography. Palgrave.

- Goodman, Kevis (2014). "Conjectures on Beachy Head: Charlotte Smith's Geological Poetics and the Grounds of the Present". Elh. 81 (3): 983–1006. doi:10.1353/elh.2014.0033.

- Gurton-Wachter, Lily. Watchwords: Romanticism and the Poetics of Attention. Stanford University Press, 2016, Ebook, p. 114.

- Haekel, Ralf (2017). "Charlotte Smith, Beachy Head (1807)". Handbook of British Romanticism: 339–358.

- Haekel, Ralf. Handbook of British Romanticism. De Gruyter Mouton, 2017.

- Holt, Kelli M. “Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head: Science and the Dual Affliction of Minute Sympathy.” ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts 1640-1830, vol. 4, no. 1, 2014. scholarcommons.usf.edu/abo/vol4/iss1/3/#.XjsYycogHQo.link. Accessed 20 Jan. 2020.

- Hunt, Olly. “Melancholia in Charlotte Smith’s Verse.” Online Journal of Literary Criticism and Creativity, issue 3, 16 November 2012.

- Kazan, Elia. “Mimesis in Beachy Head: How Coastal Fragmentation Informs Charlotte Smith’s Poetry.” Retrieved from https://eliakazanblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/final-paper-romanticism-and-e cocriticism.pdf.

- Keane, Angela (2012). Revolutionary Women Writers : Charlotte Smith & Helen Maria Williams. Northcote House.

- Kelley, Theresa. “Romantic Histories: Charlotte Smith and Beachy Head” Nineteenth-Century Literature 59.3 (2005): 281–314.

- Labbe, Jacqueline (2015). Charlotte Smith in British Romanticism. Routledge. pp. 45–56.

- Labbe, Jacqueline M. Charlotte Smith: Romanticism, Poetry and the Culture of Gender. Manchester University Press, 2011, pp. 8.

- Landry, Donna. "Green Languages? Women Poets as Naturalists in 1653 and 1807." Huntington Library Quarterly Vol. 63, No. 4, Forging Connections: Women's Poetry from the Renaissance to Romanticism (2000), pp. 467–489.

- Lokke, K. “The Figure of the Hermit in Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head." The Wordsworth Circle, 39(1), 2008, 38-43.

- Radu, Anca-Raluca (2017). Haekel, Ralf (ed.). "Handbook of British Romanticism". De Gruyter, Inc.

Created from unb on 2020-02-03 07:41:55

- Ruwe, Donelle (1999). "Charlotte Smith's Sublime: Feminine Poetics, Botany, and Beachy Head". Essays in Romanticism. 7 (1): 117–132. doi:10.3828/EIR.7.1.7.

- Ruwe, Donelle (2016-04-02). "Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head and the Lyric Mode". Pedagogy. 16 (2): 300–307. doi:10.1215/15314200-3435916. ISSN 1533-6255.

- Shelley, Julia Catherine. The Aesthetic Politics of Landscape in the Poetry of Charlotte Smith. pp 41–72, 1992.

- Singer, Katherine (2012-06-23). "Charlotte Smith: Beachy Head". In Robinson, Daniel (ed.). The Literary Encyclopedia. 1.2.1.06: English Writing and Culture of the Romantic Period, 1789-1837.

- Schabert, Ina (2014). "From Feminist to Integrationist Literary History: 18th Century Studies 2005–2013". Literature Compass. 11 (10): 667–676. doi:10.1111/lic3.12179. ISSN 1741-4113.

- Smith, Charlotte. From “Beachy Head.” The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Age of Romanticism, Volume 4, edited by Joseph Black et al., Broadview Press, 2018, pp. 49–63.

- Tayebi, Kandi. “Undermining the Eighteenth-Century Pastoral: Rewriting the Poet’s Relationship to Nature in Charlotte Smith’s Poetry.” European Romantic Review 15.1 (2004): 131–50.

- Wallace, Anne D. "Interfusing Living and Nonliving in Charlotte Smith's Beachy Head." The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 50, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1–19.

- Wallace, Anne D. “Picturesque Fossils, Sublime Geology? The Crisis of Authority in Charlotte Smith’s Beachy Head.” European Romantic Review 12 (2002): 77–93.

- Jacobs, Amanda. The Song Cycles of Beachy Head

- Heringman, Noah. Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology. Cornell University Press, 2004.

- Radu, Anca-Raluca. “Chapter 24 - Charlotte Smith, Beachy Head (1807).” Handbook of British Romanticism, edited by Ralf Haekel, De Gruyter Inc., 2017, pp. 439–458.

- Strand, Mark, et al. The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms. Norton, 2000.