Battle of Pharsalus

The Battle of Pharsalus was the decisive battle of Caesar's Civil War. On 9 August 48 BC at Pharsalus in central Greece, Gaius Julius Caesar and his allies formed up opposite the army of the republic under the command of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus ("Pompey the Great"). Pompey had the backing of a majority of the senators, of whom many were optimates, and his army significantly outnumbered the veteran Caesarian legions.

| Battle of Pharsalus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Caesar's Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Caesarians | Pompeians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Julius Caesar Mark Antony Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus Publius Cornelius Sulla |

Pompey Titus Labienus Metellus Scipio Lucius Ahenobarbus † Lucius Cornelius Lentulus | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,000 legionaries 1,000 cavalry |

40,000 legionaries[1][2][3] 3,000–6,700 cavalry | ||||||

| Uncounted amounts of auxiliary and allied infantry | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 230–1,200 killed[4] |

6,000 killed (Pollio)[5] Surrender of most troops | ||||||

The two armies confronted each other over several months of uncertainty, Caesar being in a much weaker position than Pompey. The former found himself isolated in a hostile country with only 22,000 legionaries and short of provisions, while on the other side of the river he was faced by Pompey with an army about twice as large in number. Pompey wanted to delay, knowing the enemy would eventually surrender from hunger and exhaustion. Pressured by the senators present and by his officers, he reluctantly engaged in battle and suffered an overwhelming defeat, ultimately fleeing the camp and his men, disguised as an ordinary citizen. However, Pompey was later assassinated in Ptolemaic Egypt by orders of Ptolemy XIII.

Prelude

A dispute between Caesar and the optimates faction in the Senate of Rome culminated in Caesar marching his army on Rome and forcing Pompey, accompanied by much of the Roman Senate, to flee in 49 BC from Italy to Greece, where he could better conscript an army to face his former ally. Caesar, lacking a fleet to immediately give chase, solidified his control over the western Mediterranean – Spain specifically – before assembling ships to follow Pompey. Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, whom Pompey had appointed to command his 600-ship fleet, set up a massive blockade to prevent Caesar from crossing to Greece and to prevent any aid to Italy. Caesar, defying convention, chose to cross the Adriatic during the winter, with only half his fleet at a time.

Caesar was now in a precarious position, holding a beachhead at Epirus with only half his army, no ability to supply his troops by sea, and limited local support, as the Greek cities were mostly loyal to Pompey. Caesar's only choice was to fortify his position, forage what supplies he could, and wait on his remaining army to attempt another crossing. Pompey by now had a massive international army; however, his troops were mostly untested raw recruits, while Caesar's troops were hardened veterans. Realizing Caesar's difficulty in keeping his troops supplied, Pompey decided to simply mirror Caesar's forces and let hunger do the fighting for him. Caesar began to despair and used every channel he could think of to pursue peace with Pompey. When this was rebuffed he made an attempt to cross back to Italy to collect his missing troops, but was turned back by a storm. Finally, Mark Antony rallied the remaining forces in Italy, fought through the blockade and made the crossing, reinforcing Caesar's forces in both men and spirit. Now at full strength, Caesar felt confident to take the fight to Pompey.

Pompey was camped in a strong position just south of Dyrrhachium with the sea to his back and surrounded by hills, making a direct assault impossible. Caesar ordered a wall to be built around Pompey's position in order to cut off water and pasture land for his horses. Pompey built a parallel wall and in between a kind of no man's land was created, with fighting comparable to the trench warfare of World War I. Ultimately the standoff was broken when a traitor in Caesar's army informed Pompey of a weakness in Caesar's wall. Pompey immediately exploited this information and forced Caesar's army into a full retreat, but ordered his army not to pursue, fearing Caesar's reputation for setting elaborate traps. This caused Caesar to remark, "Today the victory had been the enemy's, had there been any one among them to gain it."[6] Pompey continued his strategy of mirroring Caesar's forces and avoiding any direct engagements. After trapping Caesar in Thessaly, the prominent senators in Pompey's camp began to argue loudly for a more decisive victory. Although Pompey was strongly against it — he wanted to surround and starve Caesar's army instead — he eventually gave in and accepted battle from Caesar on a field near Pharsalus.

Excerpt from Cassius Dio's "Roman History" gives a more ancient flavor of his take on the prelude to the "Battle of Pharsalus": [41.56] "As a result of these circumstances and of the very cause and purpose of the war a most notable struggle took place. For the city of Rome and its entire empire, even then great and mighty, lay before them as the prize, since it was clear to all that it would be the slave of him who then conquered. When they reflected on this fact and furthermore thought of their former deeds [...41.57] they were wrought up to the highest pitch of excitement....they now, led by their insatiable lust of power, hastened to break, tear, and rend asunder. Because of them Rome was being compelled to fight both in her own defense and against herself, so that even if victorious she would be vanquished."

Date

The date of the actual decisive battle is given as 9 August 48 BC according to the republican calendar. According to the Julian calendar however, the date was either 29 June (according to Le Verrier's chronological reconstruction) or possibly 7 June (according to Drumann/Groebe). As Pompey was assassinated on 3 September 48 BC, the battle must have taken place in the true month of August, when the harvest was becoming ripe (or Pompey's strategy of starving Caesar would not be plausible).

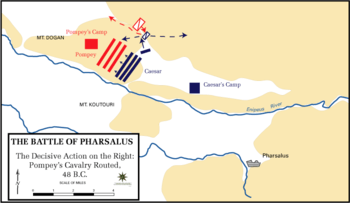

Location

The location of the battlefield was for a long time the subject of controversy among scholars. Caesar himself, in his Commentarii de Bello Civili, mentions few place-names;[7] and although the battle is called after Pharsalos by modern authors, four ancient writers – the author of the Bellum Alexandrinum (48.1), Frontinus (Strategemata 2.3.22), Eutropius (20), and Orosius (6.15.27) – place it specifically at Palaepharsalus ("Old" Pharsalus). Strabo in his Geographica (Γεωγραφικά) mentions both old and new Pharsaloi, and notes that the Thetideion, the temple to Thetis south of Scotoussa, was near both. In 198 BC, in the Second Macedonian War, Philip V of Macedon sacked Palaepharsalos (Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 32.13.9), but left new Pharsalos untouched. These two details perhaps imply that the two cities were not close neighbours. Many scholars, therefore, unsure of the site of Palaepharsalos, followed Appian (2.75) and located the battle of 48 BC south of the Enipeus or close to Pharsalos (today's Pharsala).[8] Among the scholars arguing for the south side are Béquignon (1928), Bruère (1951), and Gwatkin (1956).

An increasing number of scholars, however, have argued for a location on the north side of the river. These include Perrin (1885), Holmes (1908), Lucas (1921), Rambaud (1955), Pelling (1973), Morgan (1983), and Sheppard (2006). John D. Morgan in his definitive “Palae-pharsalus – the Battle and the Town”,[9] shows that Palaepharsalus cannot have been at Palaiokastro, as Béquignon thought (a site abandoned c. 500 BC), nor the hill of Fatih-Dzami within the walls of Pharsalus itself, as Kromayer (1903, 1931) and Gwatkin thought; and Morgan argues that it is probably also not the hill of Khtouri (Koutouri), some 7 miles north-west of Pharsalus on the south bank of the Enipeus, as Lucas and Holmes thought, although that remains a possibility. However, Morgan believes it is most likely to have been the hill just east of the village of Krini (formerly Driskoli) very close to the ancient highway from Larisa to Pharsalus.[10] This site is some six miles (10km) north of Pharsalus, and three miles north of the river Enipeus, and not only has remains dating back to neolithic times but also signs of habitation in the 1st century BC and later. The identification seems to be confirmed by the location of a place misspelled "Palfari" or "Falaphari" shown on a medieval route map of the road just north of Pharsalus. Morgan places Pompey's camp a mile to the west of Krini, just north of the village of Avra (formerly Sarikayia), and Caesar's camp some four miles to the east-south-east of Pompey's. According to this reconstruction, therefore, the battle took place not between Pharsalus and the river, as Appian wrote, but between Old Pharsalus and the river.

An interesting side-note on Palaepharsalus is that it was sometimes identified in ancient sources with Phthia, the home of Achilles.[11] Near Old and New Pharsalus was a "Thetideion", or temple dedicated to Thetis, the mother of Achilles. However, Phthia, the kingdom of Achilles and his father Peleus, is more usually identified with the lower valley of the Spercheios river, much further south.[12][13]

Name of the battle

Although it is often called the Battle of Pharsalus by modern historians, this name was rarely used in the ancient sources. Caesar merely calls it the proelium in Thessaliā ("battle in Thessalia"); Marcus Tullius Cicero and Hirtius call it the Pharsālicum proelium ("Pharsalic battle") or pugna Pharsālia ("Pharsalian battle"), and similar expressions are also used in other authors. But Hirtius (if he is the author of the de Bello Alexandrino) also refers to the battle as having taken place at Palaepharsalus, and this name also occurs in Strabo, Frontinus, Eutropius, and Orosius. Lucan in his poem about the Civil War regularly uses the name Pharsālia, and this term is also used by the epitomiser of Livy and by Tacitus.[14] The only ancient sources to refer to the battle as being at Pharsalus are a certain calendar known as the Fasti Amiternini and the Greek authors Plutarch, Appian, and Polyaenus.[15] It has therefore been argued by some scholars that "Pharsalia" would be a more accurate name for the battle than Pharsalus.[16]

Opposing armies

Caesarian army

Caesar gives his own numbers as 22,000 men in eighty cohorts (it should be remembered that these numbers refer to legionaries, and do not include non-Roman infantry) and 1,000 cavalry (mainly Germanic and Gallic auxiliaries).[17]

Caesar had the following legions with him:

- Legions of veterans from the Gallic Wars – Caesar's favourite legion, X Equestris, and those later known with the names of VIII Augusta, IX Hispana, and XII Fulminata

- Legions levied for the civil war – legions later known as I Germanica, III Gallica, and IV Macedonica

However, all of these legions were understrength. Some only had about a thousand men at the time of Pharsalus, due partly to losses at Dyrrhachium and partly to Caesar's wish to rapidly advance with a picked body as opposed to a ponderous movement with a large army.[18]

Pompeian army

Aside from 5 legions Pompey had brought over from Italy, he had one from Cilicia, one from Greece, and acquired two more from Asia raised by the consul Lentulus.[19] He distributed amongst them a number of veteran re-enlistees from Greece, as well as the elements of 15 cohorts captured from Caesar's supporter Gaius Antonius in Illyria.[20] Pompey at some point was reinforced by some cohorts which had fled Caesar's onslaught in Spain,[21] and was awaiting another two legions from Syria to be brought by his father-in-law, Metellus Scipio.[22] This brought the army's strength to a total of 11 legions, of which 88 cohorts were fielded at Pharsalus, comprising altogether some 40,000 heavy infantry.[23][lower-alpha 1] Pompey's auxiliary infantry and cavalry outnumbered Caesar's own by far (though their exact amount is unclear) and were remarkably diverse, including a handful of Gallic and Germanic cavalry and all polyglot peoples of the east – Phoenicians, Cretan slingers and other Greeks, Jews, Arabs, Anatolians, Armenians, and others – to which heterogeneous force Pompey added horsemen conscripted from his own slaves.[25] Many of the foreigners were serving under their own rulers, for more than a dozen despots and petty kings under Roman influence in the east were Pompey's personal clients and some elected to attend in person, or send proxies.[25][lower-alpha 2] Of Pompey's cavalry specifically, Sheppard suggests that Pompey still had 6,700 men with him at Pharsalus,[28] but Hans Delbrück believed the number to be much lower, 3,000 by his speculation.[29]

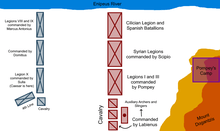

Deployment

On the Pharsalian plain, Pompey deployed his army with its right flank against the river.[30] Each cohort of Roman infantry was formed in a much thicker formation than usual, 10 men deep, in order to prevent the men in the front line from fleeing[31] and enable his troops to absorb the shock of Caesar's attack.[32] With this in mind, they were to tie down Caesar's infantry and thus give time for the superior Pompeian cavalry to overwhelm the enemy's own and subsequently attack Caesar's flank and rear.[33] As a precaution, 500–600 Pontic horsemen and some Cappadocian light infantry were placed on the right flank;[34] but, trusting that the river would provide sufficient protection to this wing, Pompey concentrated the bulk of the cavalry, his key to victory, in the left flank.

Pompey's legions were arrayed in the traditional three line formation (triplex acies): four cohorts in the front line and three in the second and third lines each.[35] He stationed in the center and wings the troops in which he placed most confidence: on the left stood the two legions which Caesar had given to the Senate shortly before the civil war began, while the two legions brought from Syria by Scipio were placed in the middle, and on the right the legion from Cilicia together with the cohorts brought from Spain; the space between these experienced soldiers was filled with raw recruits.[36] Pompey also dispersed 2,000 re-enlisted veterans from his previous campaigns throughout the entire army in order to strengthen its ranks.[37] The infantry column was divided under command of three subordinates, with L. Lentulus in charge of Pompey's left, Scipio of the center and L. Domitius Ahenobarbus the right.[38] Pompey himself took up a position behind the left wing in order to oversee the course of the battle,[39] while the cavalry on that wing was placed under command of Titus Labienus, a former lieutenant of Caesar.[28]

Caesar also deployed his men in three lines, but, being outnumbered, had to thin his ranks to a depth of only six men, in order to match the frontage presented by Pompey. His left flank, resting on the Enipeus River, consisted of his battle worn IXth legion supplemented by the VIIIth legion, these were commanded by Mark Antony. The VI, XII, XI and XIII formed the centre and were commanded by Domitius, then came the VII and upon his right he placed his favored Xth legion, giving Sulla command of this flank — Caesar himself took his stand on the right, across from Pompey. Upon seeing the disposition of Pompey's army Caesar grew discomforted, and further thinned his third line in order to form a fourth line on his right: this to counter the onslaught of the enemy cavalry, which he knew his numerically inferior cavalry could not withstand. He gave this new line detailed instructions for the role they would play, hinting that upon them would rest the fortunes of the day, and gave strict orders to his third line not to charge until specifically ordered.

Battle

There was significant distance between the two armies, according to Caesar.[40] Pompey ordered his men not to charge, but to wait until Caesar's legions came into close quarters; Pompey's adviser Gaius Triarius believed that Caesar's infantry would be fatigued and fall into disorder if they were forced to cover twice the expected distance of a battle march. Also, stationary troops were expected to be able to defend better against pila throws.[41] Seeing that Pompey's army was not advancing, Caesar's infantry under Mark Antony and Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus started the advance. As Caesar's men neared throwing distance, without orders, they stopped to rest and regroup before continuing the charge;[42] Pompey's right and centre line held as the two armies collided.

As Pompey's infantry fought, Labienus ordered the Pompeian cavalry on his left flank to attack Caesar's cavalry; as expected they successfully pushed back Caesar's cavalry. Caesar then revealed his hidden fourth line of infantry and surprised Pompey's cavalry charge; Caesar's men were ordered to leap up and use their pila to thrust at Pompey's cavalry instead of throwing them. Pompey's cavalry panicked and suffered hundreds of casualties. After failing to reform, the rest of the cavalry retreated to the hills, leaving the left wing of Pompey's legions exposed. Caesar then ordered in his third line, containing his most battle-hardened veterans, to attack. This broke Pompey's left wing troops, who fled the battlefield.[43]

After routing Pompey's cavalry, Caesar threw in his last line of reserves[44] —a move which at this point meant that the battle was more or less decided. Pompey lost the will to fight as he watched both cavalry and legions under his command break formation and flee from battle, and he retreated to his camp, leaving the rest of his troops at the centre and right flank to their own devices. He ordered the garrisoned auxiliaries to defend the camp as he gathered his family, loaded up gold, and threw off his general's cloak to make a quick escape. As the rest of Pompey's army were left confused, Caesar urged his men to end the day by routing the rest of Pompey's troops and capturing the Pompeian camp. They complied with his wishes; after finishing off the remains of Pompey's men, they furiously attacked the camp walls. The Thracians and the other auxiliaries who were left in the Pompeian camp, in total seven cohorts, defended bravely, but were not able to fend off the assault.[43]

Caesar had won his greatest victory, claiming to have only lost about 200 soldiers and 30 centurions.[45] In his history of the war, Caesar would praise his own men's discipline and experience, and remembered each of his centurions by name. He also questioned Pompey's decision not to charge.[46]

Aftermath

Pompey fled from Pharsalus to Egypt, where he was assassinated on the order of Ptolemy XIII. Ptolemy XIII sent Pompey's head to Caesar in an effort to win his favor, but instead secured him as a furious enemy. Ptolemy, advised by his regent, the eunuch Pothinus, and his rhetoric tutor Theodotus of Chios, had failed to take into account that Caesar was granting amnesty to a great number of those of the senatorial faction in their defeat. Even men who had been bitter enemies were allowed not only to return to Rome but to assume their previous positions in Roman society.

Pompey's assassination had deprived Caesar of his ultimate public relations moment — pardoning his most ardent rival. The Battle of Pharsalus ended the wars of the First Triumvirate. The Roman Civil War, however, was not ended. Pompey's two sons, Gnaeus Pompeius and Sextus Pompey, and the Pompeian faction, led now by Metellus Scipio and Cato, survived and fought for their cause in the name of Pompey the Great. Caesar spent the next few years 'mopping up' remnants of the senatorial faction. After seemingly vanquishing all his enemies and bringing peace to Rome, he was assassinated in 44 BC by friends, in a conspiracy organized by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus.

Importance

Paul K. Davis wrote that "Caesar's victory took him to the pinnacle of power, effectively ending the Republic."[47] The battle itself did not end the civil war but it was decisive and gave Caesar a much needed boost in legitimacy. Until then much of the Roman world outside Italy supported Pompey and his allies due to the extensive list of clients he held in all corners of the Republic. After Pompey's defeat former allies began to align themselves with Caesar as some came to believe the gods favored him, while for others it was simple self-preservation. The ancients took great stock in success as a sign of favoritism by the gods. This is especially true of success in the face of almost certain defeat — as Caesar experienced at Pharsalus. This allowed Caesar to parlay this single victory into a huge network of willing clients to better secure his hold over power and force the Optimates into near exile in search for allies to continue the fight against Caesar.

In popular culture

The battle gives its name to the following artistic, geographical, and business concerns:

- Pharsalia, a poem by Lucan

- Pharsalia, New York, U.S.

- Pharsalia Technologies, Inc.

In Alexander Dumas' The Three Musketeers, the author makes reference to Caesar's purported order that his men try to cut the faces of their opponents - their vanity supposedly being of more value to them than their lives.[48]

Notes

- Caesar put the strength of Pompey's legionaries at 45,000 regular soldiers plus 2,000 re-enlisted veterans in 110 cohorts (11 legions), but neglected to subtract 7 cohorts left to guard the camp and failed to mention altogether another 15 left behind at Dyrrachium on garrison duty.[1][2][3] The figure of 40,000 legionaries in 88 cohorts, which tallies with the number of cohorts detached (22 from 110), is given by Eutropius and Orosius,[24] following Livy and probably, ultimately, Caesar's officer Gaius Asinius Pollio. Brunt suggested that Caesar's figure of 47,000 corresponds to the whole of Pompey's army, not all of which fought at Pharsalus.[2][3]

- Caesar mentions that Pompey raised 7,000 cavalry, 3,000 archers and two 600-strong cohorts of slingers (before Dyrrachium),[26] but many of these men would be used for garrisoning and other non-combat-related duties.[27]

- Fields 2008, pp. 55, 62.

- Brunt 1971, pp. 691–692.

- Delbrück 1975, p. 545.

- Appian, 2.82.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 430.

- Plutarch Pompey 65.5, Dryden translation: p. 465.

- Bellum Civile 3.81–98

- Map with conjectured locations, Annual of the British School at Athens, No. XXIV, 1921

- The American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 87, No. 1, Jan. 1983

- See Google maps.

- Holmes (1908), p. 275; cf. Strabo, Geography, 9.5.6; Little Iliad frag. 19; Euripides Andromache 16ff.

- Allen, T. W. (1906). "Μυρμιδόνων Πόλις". The Classical Review, Vol. 20, No. 4 (May, 1906), pp. 193-201; cf. p. 196.

- Phthia in Brill's New Paully encyclopaedia.

- Morgan (1983), p. 27.

- Morgan (1983), p. 27.

- Postgate (1905); Bruère (1951).

- John Leach, Pompey the Great, p. 204; P. A. Brunt, Italian Manpower, p. 691; Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili, III, 89.2.

- "Battle of Pharsalus". militaryhistory.com. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- Sheppard 2006, p. 37.

- Sheppard 2006, pp. 37–38.

- Fields 2008, p. 62.

- Sheppard 2006, p. 38.

- Fields 2008, pp. 55, 62; Brunt 1971, pp. 691–692; Delbrück 1975, p. 545.

- Eutropius, 6.20; Orosius, 6.15.23.

- Sheppard 2006, pp. 38, 60–61.

- Caesar, 3.88.

- Appian, 2.49.

- Sheppard 2006, p. 61.

- Delbrück 1975, p. 549.

- Delbrück 1975, p. 538.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 425.

- Sheppard 2006, p. 60.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 425–426.

- Eutropius, 6.20; Frontinus, 2.3.22; Lucan, 7.224–226; Sheppard 2006, p. 61.

- Sheppard 2006, pp. 56, 57.

- Frontinus, 2.3.22; Caesar, 3.88.4.

- Sheppard 2006, p. 60; Delbrück 1975, pp. 423, 456, 457, 545; Caesar, 3.88.5.

- Lucan, 7.217–223; Caesar, 3.88. 2–3, 6; Morgan 1983, p. 54.

- Sheppard 2006, p. 56.

- Caesar, BC III 92,1.

- Caesar, BC III, 92,2.

- Caesar, BC III, 93,1.

- https://www.academia.edu/19860273/48_BC_The_Battle_of_Pharsalus

- Caesar, BC III, 93,4

- Caesar, BC III 99,1.

- Caesar, BC III, 92,3.

- Paul K. Davis, 100 Decisive Battles from Ancient Times to the Present: The World’s Major Battles and How They Shaped History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 59.

- Dumas, Alexander (2009). The Three Musketeers. Oxford University Press. p. 620. ISBN 0199538468.

References

Ancient sources

Modern sources

- Brunt, P.A. (1971). Italian Manpower 225 B.C. – A.D. 14. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814283-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delbrück, Hans (1975) [1900]. History of the Art of War volume 1: Warfare in Antiquity. Translated by Walter J. Renfroe Jr. (3rd ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6584-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fields, Nic (2008). The Roman Army: the Civil Wars 88–31 BC. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-262-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). Caesar: The Life of a Colossus. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84620-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, John D. (1983). "Palaepharsalus – The Battle and the Town". American Journal of Archaeology. 87 (1): 23–54. JSTOR 504663.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheppard, Simon (2006). Pharsalus 48 BC: Caesar and Pompey – Clash of the Titans (PDF). Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-002-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bruère, Richard Treat, (1951). "Palaepharsalus, Pharsalus, Pharsalia". Classical Philology, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Apr., 1951), pp. 111-115.

- Gwatkin, William E. (1956). "Some Reflections on the Battle of Pharsalus", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 87.

- James, Steven (2016). "48 BC: The Battle of Pharsalus". Non-peer-reviewed publication.

- Holmes, T. Rice (1908). "The Battle-Field of Old Pharsalvs" (The Battle-Field of Old Pharsalus). The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Oct., 1908), pp. 271-292.

- Lucas, Frank Laurence (1921). "The Battlefield of Pharsalos", Annual of the British School at Athens, No. XXIV, 1919–21.

- Nordling, John G. (2006). "Caesar's Pre-Battle Speech at Pharsalus (B.C. 3.85.4): Ridiculum Acri Fortius ... Secat Res". The Classical Journal, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Dec. - Jan., 2005/2006), pp. 183-189.

- Pelling, C. B. R. (1973). "Pharsalus". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. Bd. 22, H. 2 (2nd Qtr., 1973), pp. 249-259.

- Perrin, B. (1885). "Pharsalia, Pharsalus, Palaepharsalus". The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 6, No. 2 (1885), pp. 170-189.

- Postgate, J. P. (1905). "Pharsalia Nostra". The Classical Review, Vol. 19, No. 5 (Jun., 1905), pp. 257-260.

- Rambaud, Michel (1955). "Le Soleil de Pharsale", Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte , Vol.3, No.4.

- Searle, Arthur (1907). "Note on the Battle of Pharsalus". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 18 (1907), pp. 213-218.

- Wylie, Graham (1992). "The Road to Pharsalus". Latomus, T. 51, Fasc. 3 (Juillet-Septembre 1992), pp. 557-565.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Pharsalus. |