Battle of Ningpo

During the First Opium War (1839-1842) British forces captured and occupied the important Chinese port city of Ningpo in October 1841. After several months of harsh occupation, a Chinese force was sent to liberate the city. The subsequent battle in March 1842 resulted in a British victory and the scattering of Chinese forces in the region.

| Battle of Ningpo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Opium War | |||||||

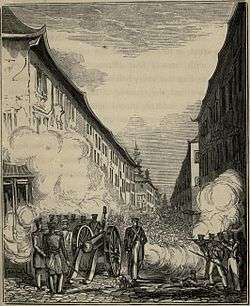

The British repulse the Chinese advance in the city | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sir Hugh Gough | General I-Ching | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 700 | 3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5 wounded | 500–600 killed | ||||||

Background

Prior to the battle of Ningpo the city had roughly 250,000 inhabitants and had already had contact with the British military.[1] On 15 September 1840 the British ship HMS Kite was grounded near Ningpo. The survivors of the wreck were afterwards captured by Chinese forces and paraded through the city and countryside in small cages. This treatment would later influence British occupation forces during the Opium War when they attacked Ningpo a year later.

The following year, on 10 October 1841, the British captured Chinhai (Zhenhai) after a fierce battle between Chinese and British forces.[1] The British soon sent the HMS Nemesis up the Yung River to discover if the river was navigable. Upon discovering that the river could accommodate their large steamers, the British Navy sailed to Ningpo. On 13 October, British troops entered Ningpo under the tune of "Saint Patrick’s Day in the morning" and captured the city unopposed.[2] The capture of Ningpo was a stepping stone to launch an attack on Nanking as part of their larger strategy for taking Beijing (Peking). The British planned to occupy Nanking and move up the Grand Canal towards Beijing.[3]

British occupation of Ningpo

The British occupation of Ningpo was harsh and created tensions between the occupation force and the locals of Ningpo. Following their capture of Ningpo, many British soldiers looked forward to plundering the city as a punishment for mistreating the survivors of the Kite, however some refused to participate and prevented the plundering. Instead, the soldiers burned the prison where the Kite prisoners were held and imposed a ten percent tax on all residents, which bled the city of over £160,000.[4][5] The British also allowed Chinese freebooters to loot the city and extort money from the locals. Residents of the city often threw trash and feces at unaccompanied British soldiers during the occupation. British officers, Sir William Parker and Hugh Gough, were angry and disappointed at the lack of honor in the treatment of the Chinese.[6] However, matters only worsened with the arrival of Sir Henry Pottinger on 13 January 1842 who felt, "considerable satisfaction" with looting the city.[7] According to one historian Pottinger "ordered the confiscation of all the Chinese ships and provisions and other property, including the main pagoda’s bell, which was sent to India as another symbolic prize."[4] He appointed Reverend Dr. Karl Gutzlaff, a Prussian missionary, as the top civil magistrate in Ningpo. Dr. Gutzlaff ruled the city harshly and hired a small group of spies to monitor the city and the acts of the residents, allowing British officials to impose harsher taxes and ransoms on the rich citizens of the city.[6] The British also opened up the public granary and began to cheaply sell grains as a way to further weaken the city. They also began to personally loot individual homes and people of valuables, greatly increasing the tensions in the city.[8]

Following the loss of Ningpo the Emperor sent his cousin General Yinjing (I-ching) to Soochow to recruit men to retake the city and "drive the English into the sea."[9] However, most of the recruits were ill-trained and unprepared for combat.[10] Despite this, the Chinese forces looked to go on the offensive. They fought several small skirmishes with British troops outside of Ningpo, each time being defeated.[9] Fearful of English spies, security was heightened in the Chinese camp preventing those disloyal to the Emperor near the general.[11] Plans were made to retake the city and destroy the British ships in the Yung River. One plan was suggested to light the boats on fire using firecrackers tied to monkeys who would be flung on the ships. This plan, as well as plans to use fire rafts were both discarded prior to the battle.[12]

The battle

The battle of Ningpo was a harsh battle between the local Chinese force and the better armed British force on 9 and 10 March 1842. The Chinese had gathered over 3,000 men for the assault on the city. The original plan had been to assault the city with almost 50,000 troops, however most of these troops failed to arrive in time.[13] The British also had depleted numbers, with fewer than seven hundred soldiers.[6] However, the Chinese plan was exposed when a group of local boys who had befriended the British soldiers warned them of the coming attack.[14]

When the Chinese forces arrived at Ningpo on 10 March they found a head impaled on a spike that said, "This is the head of the Manchu official Lu Tai-lai, who came here to obtain military information." Infuriated, the attackers scaled the southern and eastern walls, overwhelming the southern gate.[9] At the western gate of Ningpo, a band of Chinese soldiers approached the walls, and seeing the west gate opened, charged forward. However, as explosions rocked the area it became apparent that the British had mined the gate. Over a hundred Chinese soldiers died as a result of the attack and the attack was aborted.[15] Meanwhile, at the southern gate it appeared as if the Chinese would be able to overwhelm the British garrison, but were repelled by 150 British soldiers under Gough’s command as they brought in a field artillery piece.[16] British officials and Chinese officials reported that many of the attackers were high on opium entering the battle, which decreased the effectiveness of the attacking force. The British used a single piece of artillery and killed over 500 Chinese soldiers.[17] Furthermore, heavy rains and mud had delayed the Chinese from swiftly bringing in reinforcements.[9]

Aftermath

Following the battle, the British continued to occupy Ningpo until the following spring when they sacked the city before departing.[7] The Chinese armies retreated from Ningpo to the town of Tz’uch’i, eighteen miles north of Ningpo where they suffered heavily from shrapnel and bullet wounds.[18] Kidnappings and murders greatly increased in the city as local Chinese residents fought back against the British occupiers. However, the British retaliation was harsh, with suspects being killed and quarters of the city being burned.[19] With the 1842 Treaty of Nanking ending the First Opium War, the city became part of the British sphere of influence in China.[20]

Notes

- Beeching 1975, p. 139.

- Fry 1975, p. 316.

- Beeching 1975, p. 138-139.

- Hanes III & Sanello 2002, p. 138.

- Beeching 1975, p. 140.

- Hanes III & Sanello 2002, p. 139.

- Inglis 1976, p. 162.

- Fry 1975, pp. 318–319.

- Fry 1975, p. 319.

- Waley 1958, p. 158.

- Waley 1958, p. 160.

- Waley 1958, p. 170.

- Waley 1958, p. 169.

- Beeching 1975, p. 145.

- Waley 1958, p. 170-171.

- Waley 1958, p. 172.

- Hanes III & Sanello 2002, p. 140.

- Waley 1958, p. 175.

- Fry 1975, p. 320.

- Chesneaux, Bastid & Bergere 1976, p. 64-65.

References

- Beeching, Jack (1975). The Chinese Opium Wars. London: Hutchinson of London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bulletins of State Intelligence. Westminster: F. Watts. 1842.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chesneaux, Jeane; Bastid, Marianne; Bergere, Marie-Claire (1976). China from the Opium Wars to the 1911 Revolution. New York: Pantheon Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fry, Peter Ward (1975). The Opium War 1840-1842. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, William Hutcheon; Bernard, William Dallas (1846). The Nemesis in China (3rd ed.). London: Henry Colburn.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanes III, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2002). The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Naperville: Sourcebooks Inc.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Inglis, Brian (1976). The Opium War. London: Hodder and Stoughton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ouchterlony, John (1844). The Chinese War. London: Saunders and Otley.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waley, Arthur (1958). The Opium War through Chinese Eyes. New York: The Macmillan Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)