Battle of Jieting

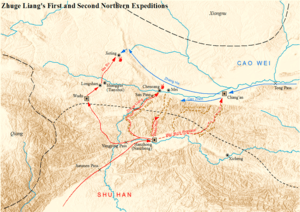

The Battle of Jieting was fought between the states of Cao Wei and Shu Han in 228 during the Three Kingdoms period in China. The battle was part of the first Northern Expedition led by Shu's chancellor-regent, Zhuge Liang, to attack Wei. The battle concluded with a decisive victory for Wei.

| Battle of Jieting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the first of Zhuge Liang's Northern Expeditions | |||||||

A Qing dynasty illustration of Ma Su's execution | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cao Wei | Shu Han | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Zhang He |

Ma Su Wang Ping | ||||||

| Battle of Jieting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 街亭之戰 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 街亭之战 | ||||||

| |||||||

Opening moves

Zhuge Liang first sent generals Zhao Yun and Deng Zhi to attack Wei, while he personally led a force towards Mount Qi. Cao Rui, the emperor of Wei, moved to Chang'an and sent Zhang He to attack Zhuge Liang while Cao Zhen would oppose Zhao Yun. Zhuge Liang chose generals Ma Su and Wang Ping to intercept Zhang He.

The battle

Jieting was a crucial region for the securing of supplies, and Zhuge Liang sent Ma Su and Wang Ping to guard the region. Ma Su went accompanied by Wang Ping but did not listen to his sound military advice. Relying purely on books of military tactics, Ma Su chose to "take the high ground" and set his base on the mountains instead of in a city, ignoring Wang Ping's advice to make camp in a valley well supplied with water. Wang Ping, however, managed to persuade Ma Su to give him command of a portion of the troops, and later Wang set up his base camp near Ma's camp, in order to offer assistance when Ma was in danger. Due to this tactical mistake, the Wei army led by Zhang He encircled the hill and cut off the water supply to the Shu troops and attacked; later, Wei forces set fire to the hill. Wang Ping led his troops in an attempt to help Ma Su but the Shu army suffered a great defeat in which both the army and the fort were lost. Though he survived the battle, Ma Su feared punishment and attempted to flee. However, he was soon captured by Shu forces.

Aftermath

Ma Su was sentenced to death by Zhuge Liang, along with his deputies Zhang Xiu (張休) and Li Sheng (李盛), but Ma eventually died of illness in prison before the execution could be carried out, while the other two were executed.

Because of the loss of Jieting, the supply situation became dire for Zhuge Liang's army and he had to retreat to his main base at Hanzhong. In addition, the defeat at Jieting caused the First Northern Expedition to result in failure.

In Romance of the Three Kingdoms

In the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Ma Su was executed on the order of a tearful Zhuge Liang, whose continued high appraisal for Ma's intelligence made that a very reluctant decision. The scene has also been reenacted in Chinese opera. A Chinese proverb, "wiping away tears and executing Ma Su" (挥泪斩马谡; 揮淚斬馬謖; Huī Lèi Zhán Mǎ Sù), refers specifically to this incident, meaning "punishing a person for his wrongdoings regardless of relations or his abilities. A Japanese equivalent is "tearfully executing Ma Su" (泣いて馬謖を斬る, Naite Bashoku wo kiru).

In the novel, the loss of Jieting exposed Zhuge Liang's current location, the defenceless Xicheng (西城). Zhuge Liang used the Empty Fort Strategy to ward off the enemy before retreating.

In many stories, including the novel, the battle includes Sima Yi on the Wei side, but this event is impossible according to his biography in the Records of the Three Kingdoms. Moss Roberts comments on this in his fourth volume of his English translation of Romance of the Three Kingdoms on (page 2179 under Chapter 95 Notes, fourth and last paragraph of the chapter notes):

- The historical Sima Yi was not at the western front for the "vacant city ruse" but at the more important southern front with the Southland [Wu]. Sima Yi did not come to the western front until Kongming's [Zhuge Liang] fourth offensive [Battle of Mount Qi]. The fictional tradition tends to attach more importance to the Wei-Shu conflict than the Wei-Wu conflict, and Three Kingdoms accordingly builds up the Kongming-Sima Yi rivalry and the events of AD 228.[2]

In the abstract theory above, Roberts explains and compares historic history with fictional tales and the most likely reason Sima Yi was included before the Battle of Mount Qi. Based on Robert's view of the fictional novel's tendency to build up the rivalry between Sima Yi and Zhuge Liang, and the contradiction of Sima Yi's location at the time of this event, some share Robert's opinion that the event did not happen. However, many historians agree that Sima Yi's absence alone cannot disprove the occurrence. The historical basis for the event comes from an anecdote shared by Guo Chong (郭沖) in the early Jin dynasty (265–420). The anecdote is translated as follows:

"Zhuge Liang garrisoned at Yangping (陽平; around present-day Hanzhong, Shaanxi) and ordered Wei Yan to lead the troops east. He left behind only 10,000 men to defend Yangping. Sima Yi led 200,000 troops to attack Zhuge Liang and he took a shortcut, bypassing Wei Yan's army and arriving at a place 60 li away from Zhuge Liang's location. Upon inspection, Sima Yi realised that Zhuge Liang's city was weakly defended. Zhuge Liang knew that Sima Yi was near, so he thought of recalling Wei Yan's army back to counter Sima Yi, but it was too late already and his men were worried and terrified. Zhuge Liang remained calm and instructed his men to hide all flags and banners and silence the war drums. He then ordered all the gates to be opened and told his men to sweep and dust the ground. Sima Yi was under the impression that Zhuge Liang was cautious and prudent, and he was baffled by the sight before him and suspected that there was an ambush. He then withdrew his troops. The following day, Zhuge Liang clapped his hands, laughed, and told an aide that Sima Yi thought that there was an ambush and had retreated. Later, his scouts returned and reported that Sima Yi had indeed retreated. Sima Yi was very upset when he found out later."

Later, in the fifth century, Pei Songzhi added the anecdote as an annotation to Zhuge Liang's biography in the Sanguozhi. Since Zhuge Liang wrote on the use of this tactic in his compilation work, "Thirty Six Stratagems", going so far as to detail how the psychology employed works, and why:

"When the enemy is superior in numbers and your situation is such that you expect to be overrun at any moment, then drop all pretense of military preparedness, act calmly, and taunt the enemy, so that the enemy will think you have a huge ambush hidden for them. It works best by acting calm and at ease when your enemy expects you to be tense. This ploy is only successful if in most cases you do have a powerful hidden force and only sparsely use the empty fort strategy."

Also worthy of note is that Zhuge Liang wrote this passage in his sixth chapter, titled "Desperate Stratagems", (敗戰計/败战计, Bài zhàn jì), further supporting the implication that he had experience in using this tactic, and his description does match the situation described by Guo Chong. However, there are a number of texts that dispute the accuracy of Guo Chong's anecdote.[3][4]

In popular culture

The battle is featured as a playable stage in Koei's video game series Dynasty Warriors for the PlayStation 2. If the player is playing on the Wei side, he has the option of following history to win the stage easily. On the other hand, if the player is playing on the Shu side, he will encounter a higher level of difficulty since one of his major objectives is to ensure the survival of Ma Su.

In the collectible card game Magic: The Gathering there is a card named Empty City Ruse in reference to the Empty Fort Strategy described in the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

References

- Zizhi Tongjian vol. 71.

- Roberts, Moss (1976). Three Kingdoms Volume IV. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. p. 2179. ISBN 978-7-119-00590-4.

- Empty Fort Strategy

- Thirty-Six Stratagems#The empty fort strategy

- Chen Shou. Records of Three Kingdoms, Volume 17, Biography of Zhang He.

- Luo Guanzhong. Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Chapters 95-96.