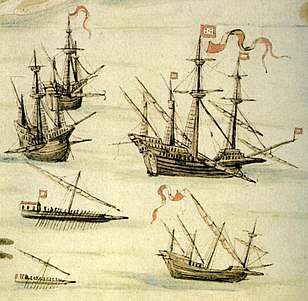

Battle of Cape St. Vincent (1606)

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent was a naval engagement that took place on 16 June or 6 October 1606, during the Eighty Years' War. A Spanish fleet under Admiral Luis Fajardo attacked the Dutch fleet led by Admiral Willem Haultain and Vice Admiral Regnier Klaazoon, which was blocking the Portuguese coast to intercept the Spanish treasure fleet. The battle concluded in a Spanish victory; in which Klaazoon's flagship was destroyed, two ships were captured and Haultain fled with the rest of the fleet to his country without having achieved his purpose.

Background

In 1604 the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) ended with a peace treaty between Spain and England, being favorable to the first country, but the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the United Provinces was still unfolding.[1] By then, in the naval camp, Spain was weakened, lacked ships and money, while Dutch naval power had emerged and could now launch counterattacks on the Spanish coast or its overseas territories.[1][2]

Prelude

In 1606 Admiral Haultain left the Netherlands with a fleet to cruise the Spanish-Portuguese coast. The sources differ in some details of the Dutch cruise. According to the Dutch, Haultain was sent to the Portuguese coast earlier that year with a fleet of twenty-four ships to harass the Spanish-Portuguese merchant fleet, without much success.[3] In September, he returned in the company of Vice Admiral Klaazoon to continue the cruise with a fleet of nineteen war-galleots of the finest class and two yachts, which were well equipped and manned.[4] Spaniards claim that the Dutch had sixty[5] or seventy[6] ships with which they made cruises between the Azores Islands and the coast of Portugal; from Lisbon to Cape St. Vincent.[upper-alpha 1]

Spain's trade with the Indies was interrupted due to the Dutch blockade and the inability of the Spaniards to counter the threat in the absence of prepared naval means.[6] Meanwhile, Haultain captured some ships and attacked some coastal villages, but they were not the prizes he was looking for.[4] On the other hand, Admiral Fajardo was trying to organize an impromptu fleet in Lisbon to end the threat and resume commercial traffic, managing to gather galleons or naos[upper-alpha 2] after a great effort.[8]

Battle

On 16 June, according to the Spaniards[5] or on 6 October, according to the Dutch,[4] both fleets met at Cape St. Vincent. Admiral Haultain passed the headland with the purpose of intercepting the Spanish treasure fleet. When sighting Spanish ships, the Dutch thought they had found them, but instead of innocent merchants loaded with treasures, the fleet soon proved to be Admiral Fajardo's armed ships.[9] As for the number of ships of both fleets, the sources also differ. The Spanish claimed that Fajardo's fleet was twenty ships and Haultain's fleet was twenty-four, as some Dutch ships had withdrawn from the area when they learned about Fajardo's naval preparations in Lisbon.[5] The Dutch claim that the Spaniards had more than twenty-six galleons, galleys and smaller vessels, while Haultain had only fourteen ships, as some were permanently lost in a storm on the Portuguese coast.[9]

The appearance of the formidable Spanish galleons inspired panic among the Dutch sailors.[10] Haultain had a brief consultation with his main officers, and decided to hurriedly flee, since it was considered inferior conditions.[11][12] Fajardo managed to intercept and corner three ships, including the flagship of Vice Admiral Klaazoon,[12] although the Dutch claim that he remained firm while his companions fled.[10] The battle became widespread and five Spanish ships surrounded and attacked Klaazoon's ship.[12] Haultain tried to support him with five ships, but the insistence of the Spanish attack caused them to abandon the fight and flee in all directions as quickly as possible.[13] Meanwhile, the bullets of the Spanish ships caused much damage to Klaazoon's ship and killed several crew members to force their commander to surrender. Klaazoon, aware that he could not escape the Spanish ships, and not wanting to be captured, lit the gunpowder on board to explode his ship, with the agreement of the sixty surviving crew, many of them seriously wounded. Only two sailors were alive after the explosion, who were rescued by the Spaniards, but they died shortly thereafter from their wounds.[14][10] Finally, the Spanish captured two Dutch ships that surrendered and persecuted the others until they were expelled from the area.[8]

Spanish historians emphasize the merit of Fajardo's fleet by beating the Haultain fleet, since, whatever the number of Spanish and Dutch ships, the first was an impromptu force with inexperienced sailors, while the second had experience of navigation.[8][12] Dutch history criticizes Haultain's attitude,[13] which barely showed energy to fight this time, unlike the previous year when he attacked an unarmed transport's squadron in the Dover Strait.[upper-alpha 3]

Aftermath

Haultain retired to the ports of the Netherlands with the rest of his fleet, including ships that had disappeared during the storm, but with a great crack in its reputation.[17] In that way, the tactical victory of the Spaniards was completed with the strategic victory by lifting the blockade and resuming commercial traffic.[12] A few days after this event, the Spanish treasure fleet that Haultain wanted to find arrived safely in Sanlúcar, a fleet of treasures that greatly increased the depressed Spanish income.[18] They were fifteen ships under the charge of General Alonso de Ochares Galindo and General Ganevaye, who had on board, according to the registers: $1,914,176 in bullion for the king and $6,086,617 for merchants, or $8,000,000 in total, in addition to other rich cargoes.[18] The result of two years of pressure on the territories of Peru, New Spain and Brazil.[18]

The year of 1606 was nothing brilliant for naval expeditions and land campaigns of the Dutch.[10] In land campaigns in the heart of the United Provinces, Prince Maurice of Nassau confined himself to facing the threat of the Flanders Army under Ambrosio Spinola, which allowed the latter to capture some cities, although they were not decisive losses for the war.[19] The failure of Haultain was added to these precarious events, after which the Dutch made no further expeditions by land or sea that year.[20]

Notes

- According to the Spanish historian Rodríguez González, the Dutch had ships of various sizes; fleet ships, transport ships and independent privateers who harassed the area.[5]

- The “nao” was an essentially commercial type of ship, although it could be armed during periods of war.[7]

- In the middle of 1605, a Spanish convoy, under Pedro Sarmiento, was attacked and partially destroyed by Haultain in the Dover Strait.[15][16]

References

- Rodríguez González 1999, p. 71–72

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 229

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 270–271

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 271

- Rodríguez González 1999, p. 72

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 231

- Salvador, Emilia (1972). La economía valenciana en el siglo XVI (in Spanish). Valencia, España: Universidad de Valencia. p. 200.

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 232

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 271–272

- Colley Grattan 2007, p. 213

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 272

- Rodríguez González 1999, p. 73

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 272–273

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 273

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 229

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 230

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 274

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 274–275

- Colley Grattan 2007, p. 212–213

- Lothrop Motley 2011, p. 275

Bibliography

- Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón (1999). "Victorias por mar de los españoles: Los otros combates de San Vicente" (PDF). Revista General de Marina (in Spanish). Madrid, España: 71–76.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lothrop Motley, John (2011) [1867]. History of the United Netherlands: From the Death of William the Silent to the Twelve Years' Truce - 1609. IV. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-03665-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1896). Armada Española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y Aragón (in Spanish). III. Madrid, España: Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colley Grattan, Thomas (2007) [1830]. Holland: The History of the Netherlands, with a Supplementary Chapter by Julian Hawthorne. New York, USA: Cosimo Classics. ISBN 978-1-60206-126-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)