Battle of Aquae Sextiae

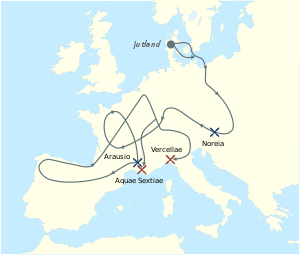

The Battle of Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) took place in 102 BC. After a string of Roman defeats (see: the Battle of Noreia, the Battle of Burdigala, and the Battle of Arausio), the Romans under Gaius Marius finally defeated the Teutones and Ambrones. The Teutones and the Ambrones were virtually wiped out, with the Romans claiming to have killed 200,000 and captured 90,000,[2] including large numbers of women and children who were later sold into slavery. Some of the surviving captives are reported to have been among the rebelling gladiators in the Third Servile War.[3] Local lore associates the name of the mountain, Mont St. Victoire, with the Roman victory at the battle of Aquae Sextiae, but Mistral and other scholars have debunked this theory.

| Battle of Aquae Sextiae | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cimbrian War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Teutones Ambrones |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Teutobod (POW) | Gaius Marius | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

The Battle against the Ambrones The Battle of Aquae Sextiae c. 100,000-200,000 (the warriors of the entire tribal coalition)[1] |

The Battle against the Ambrones The Battle of Aquae Sextiae c. 32,000-40,000 (six legions + auxiliaries) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 100,000–200,000 killed or captured | less than 1,000 killed | ||||||

Background

According to ancient sources, sometime around 120–115 BC, the Germanic tribe of the Cimbri left their homeland around the North Sea due to climate changes. They supposedly journeyed to the south-east and were soon joined by their neighbours the Teutones. On their way south they defeated several other Germanic tribes, but also Celtic and Germano-Celtic tribes. A number of these defeated tribes joined their migration. In 113 BC the Cimbri-Teutones confederation, led by Boiorix the Cimbric king and Teutobod of the Teutones, defeated the Scordisci. The invaders then moved on to the Danube, arriving in Noricum, home to the Roman-allied Taurisci people. Unable to hold back these new, powerful invaders on their own, the Taurisci appealed to Rome for help.[4]

The Senate commissioned Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, one of the consuls, to lead a substantial Roman army to Noricum to force the barbarians out. An engagement, later called the battle of Noreia, took place, in which the invaders, to everyone's surprise, completely overwhelmed the Legions and inflicted a devastating loss on Carbo and his men.[5]

After the Noreia victory, the Cimbri and Teutones moved westward towards Gaul. A few years later, in 109 BC, they moved along the Rhodanus River towards the Roman province in Transalpine Gaul. Another consul, Marcus Junius Silanus, was sent to take care of the renewed Germanic threat. Silanus marched his army north along the Rhodanus River in order to confront the migrating Germanic tribes. He met the Cimbri approximately 100 miles north of Arausio, a battle was fought and the Romans suffered another humiliating defeat. The Germanic tribes then moved to the lands north and east of Tolosa in south-western Gaul.[6]

To the Romans, the presence of the Germanic tribes in Gaul posed a serious threat to the stability in the area and to their prestige. Lucius Cassius Longinus, one of the consuls of 107, was sent to Gaul at the head of another large army. He first fought the Cimbri and their Gallic allies the Volcae Tectosages just outside Tolosa, and despite the huge number of tribesmen, the Romans routed them. Unfortunately for the Romans, a few days later they were ambushed while marching on Burdigala. The battle of Burdigala destroyed the Romans hope of finishing off the Cimbri and the Germanic threat continued to exist.[7]

In 106 the Romans sent their largest army yet; the senior consul of 106, Quintus Servilius Caepio, was authorized to use eight legions in an effort to end the Germanic threat once and for all. While the Romans were busy getting their army together the Volcae Tectosages had quarrelled with their Germanic guests, and had asked them to leave the area. When Caepio arrived he only found the local tribes and they sensibly decided not to fight the newly arrived legions. In 105 Caepio's command was prorogued and a further six legions were raised in Rome by Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, one of the consuls of 105, he led them to reinforce Caepio who was near Arausio. Unfortunately for the Romans, Caepio who was a patrician and Mallius Maximus who was a 'new man' did not get along. Caepio refused to take orders from Mallius Maximus who as consul outranked him. All this led to a divided Roman force with the two armies so far apart they could not support each other when the fighting started. Meanwhile, the Germanic tribes had combined their forces. First, they attacked and defeated Caepio's army and then, with great confidence, took on Mallius Maximus's army and defeated it too. The battle of Arausio was considered the greatest Roman defeat since the slaughter suffered at the battle of Cannae during the Punic Wars.[8]

In 104 BC the Cimbri and the Teutones seemed to be heading for Italy. The Romans sent the senior consul of 104, Gaius Marius, a proven and capable general, at the head of another large army. The Germanic tribes never materialized so Marius subdued the Volcae Tectosages capturing their king Copillus.[9] In 103, Sulla, one of Marius's lieutenants, succeeded in persuading the Germanic Marsi tribe to become friends and allies of Rome; they detached themselves from the Germanic confederation and went back to Germania.[10] In 102 BC the Teutones and Ambrones moved into Gallia Transalpina (the Roman province in the south of Gaul) while the Cimbri moved into Italy. Marius, as senior consul, ordered his junior partner Quintus Lutatius Catulus to keep the Cimbri out of Italy while he marched against the Teutones and Ambrones.[11]

Prelude

A quarter of a million Germanic and Gallic tribesmen, led by King Teutobod of the Teutones, had crossed the Durance river, east of where it entered the Rhône. They spread out for miles: there were about 130,000 warriors, as well as wagons, cattle, horses, and their women and children. With the Teutones, who made up the bulk of the invaders, were the Ambrones, who had around 30,000 warriors, making them second most numerous tribe in the coalition under Teutobod. Gaius Marius and his army had arrived some time earlier, Marius had used his time wisely; he had constructed a heavily fortified camp on a hill close to the river and stocked it with enough supplies to withstand a lengthy siege. The tribesmen tried to get the Romans to come out of their fort and fight them on even ground; they shouted insults and challenges, which Marius ignored. He was unwilling to give up a strongly defended position for a battle with an uncertain outcome. Marius let it be known throughout his camp that he intended to fight the barbarians, but on his terms, not theirs. The catcalls and challenges continued.[12]

A Teuton warrior even issued a challenge directly to Marius. The barbarian invited the general to join him in single combat. Marius mocked him by advising him that if the warrior desired death he should find a rope, fashion a noose and hang himself. The Teuton did not give up so Marius produced a veteran gladiator and explained to the barbarian that if he still lusted for blood he could try and slay the trained fighter for it was beneath Marius's station as a consul to reduce himself to a common brawler.[13]

After they failed to lure the Romans out they tried to wait them out, but Marius had anticipated this and his fortress was well stocked. Frustrated the tribesmen attacked the fort for three days. Assault after assault was launched at the Roman defense works, but the fortifications held and from these the Romans released a barrage of missiles, killing many barbarians and repulsing the rest. Still, the Romans did not come out and the tribal coalition decided to move on south toward Massilia, which they intended to plunder. It took several days for their entire wagon train to clear the area but, once they were out of sight, Gaius Marius followed, dogging them and waiting for an opportune moment to strike.[12]

Marius now started trailing the tribal coalition and camped alongside them, when ending each day's march he ordered his men to build a fortified camp with impressive defense works. After all the losses they took trying to take Marius's fortress on the Rhone the Teutones and Ambrones never tried to storm Marius's camp again. Marius was biding his time waiting for the barbarians to make a mistake. Fortunately for Marius, he was presented with a chance to take on part of the tribal horde when they entered the area of Aquae Sextiae.[14]

The battle

Several days after the Rhone, Marius's army camped near the Ambrones, who for some reason had decided to camp separately from their Teutonic allies, when a couple of army servants, fetching water from the river, ran into an unknown number of Ambrones bathing in the river. The bathing Ambrones, caught by surprise, called for their fellow tribesmen who were eating dinner and drinking in their camp on their side of the river. The Romans, working on their camp, heard the commotion and quickly grasped the situation. Marius's Ligurian auxiliaries, without orders from Marius, dropped their tools, took up their weapons and sprinted to their servants' aid. The Ambrones now formed a battle line and awaited the Ligurians. Many tribesmen were weighed down by food, half-naked from bathing or intoxicated.[15]

After forming their battle lines, the Ambrones started beating their swords and spears against their shields and chanting their battle cry: 'Ambrones!'. The Ligurians who were charging towards them had once been called Ambrones as well and also started to shout 'Ambrones!'. After reaching the Ambrones, the Ligurians also formed battle lines. They continued their shouting match for a while and then the battle finally ensued. While these events were taking place, Marius had formed up his legions and marched to reinforce his Ligurian auxiliaries. When the legionaries arrived at the battle, they cast their pila (the Roman throwing spear) into the Ambrones, killing several warriors or rendering their shields useless, unsheathed their gladius (the Roman short sword) and waded in. After the legions' arrival, the battle quickly turned into a rout. Marius's heavily armed, expertly trained soldiers easily overpowered the Ambrones and pushed them toward the river. The Ambrones suffered terrible losses while on the Roman side losses were very low.[16][17]

Marius did not allow a victory celebration for he knew the Teutones were still out there and feared a counter-attack. By the time the fighting ended, it was too late in the day to finish their fortified camp, leaving the Romans vulnerable. Marius sent a detachment of troops into the woods to create a great noise to disorientate the barbarians and keep them from sleeping. This would also cause his enemies to be sluggish because of lack of sleep the next day.[18] However, the night and the succeeding few days passed without incident, much to Marius' relief.[19]

While waiting, Marius sent one of his legates, Claudius Marcellus, with 3,000 troops some distance away and ordered him to remain undetected until a determined time when he would appear at the enemy rear.[20]

Since the Teutones were waiting for him on the plain near Aquae Sextiae, Marius had the opportunity to reconnoiter the area and select a suitable site for the upcoming battle. Four days after slaughtering the Ambrones, Marius marched his army onto the plain and took position on the high ground. He instructed his legionaries to stand their ground on the hill, launch javelins, draw their swords, guard themselves with their shields and thrust the enemy back. He assured his men that, since the barbarians would be charging uphill, their footing would be unsure and they would be vulnerable.[21]

Marius ordered his camp servants and all other non-combatants to march with the army. He also ordered his beasts of burden to be fashioned as cavalry horses. All of this was to create the illusion his forces were larger than they really were. He wanted the barbarians to hold back more of their warriors in reserve so his real forces would not be overwhelmed by the tribesmen's numbers.[22]

The surviving Ambrones and the Teutones, bent on revenge, eagerly awaited the upcoming confrontation and, when the Romans finally showed themselves on the Aquae Sextiae plain, charged uphill. The Romans unleashed a barrage of javelins, killing or maiming many tribesmen, then stood in close order, drew their swords and awaited the enemy at the top of the hill. Roman strategy, discipline and training asserted itself and the tribesmen were unable to dislodge the legions from their superior position. The battle continued for much of the morning, with neither side gaining the upper hand. However, the well-conditioned and disciplined legionaries slowly and systematically forced the tribal horde down the hill until both the Romans and barbarians were on level ground. This is when Claudius Marcellus and his 3,000 men loudly and viciously attacked the enemy rear. The Ambrones and Teutones were now being attacked on two fronts and confusion set in, they broke ranks and started to flee, but there was no haven to be found for most of them. The Romans relentlessly pursued them. By the end of the afternoon, most of the barbarian warriors were dead or captured. Estimates vary from 100,000 to 200,000 being slain or captured. Teutobod, the Teutonic king, and 3,000 warriors escaped the battle only to be caught by the Sequani who handed them over to Marius.[23]

Marius sent a Manius Aquillius with a report to Rome. It said that 37,000 superbly trained Romans had succeeded in defeating over 100,000 Germans in two engagements.

Aftermath

There were around 17,000 surviving warriors and many thousands of women and children who were to be sold into slavery. Roman historians recorded that 300 of the captured women committed mass suicide, which passed into Roman legends of Germanic heroism (cf Jerome, letter to Ageruchia cxxiii.8, 409 AD ):

- By the conditions of the surrender three hundred of their married women were to be handed over to the Romans. When the Teuton matrons heard of this stipulation they first begged the consul that they might be set apart to minister in the temples of Ceres and Venus; and then when they failed to obtain their request and were removed by the lictors, they slew their little children and next morning were all found dead in each other's arms having strangled themselves in the night.

The proceeds from the sale of slaves usually went to the commanding General, but in this case, Marius decided to donate the profits from the sale to his soldiers and officers. This, of course, made him even more popular than he already was with his men.[24]

Upon hearing the news, Rome went wild with relief. Finally one of their generals had defeated the Germans. Gaius Marius, as an act of gratitude, was again voted Senior Consul in absentia, with his legate Manius Aquillius as his Junior Consul. The Senate also voted for a three-day Thanksgiving; the people voted him two days more.[25]

The following year (101) Marius and the proconsul Catullus Caesar defeated the Cimbri at the battle of Vercellae, ending the German threat.

The inhabitants of Massalia, some 23 Roman miles, 30 kilometres, distant, used the bones of the fallen tribesmen to erect fences to protect their crops. The decaying corpses left the soil enriched, and for years to the region experienced extraordinary harvests largely thanks to thousands of rotting bodies fertilizing the farmers' lands.[26]

Modern Sources

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius: The Rise and Fall of Rome's saviour, 2017.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, 2014.

Ancient Sources

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives: Life of Marius.

- Frontinus, Stratagems.

- Orosius, Against the Pagans.

- Florus, Epitome of Roman History.

- Livy, Epitome of Roman History.

In fiction

- Colleen McCullough describes the battle in her novel The First Man in Rome, the first book in her Masters of Rome series.

Notes and References

- The entire tribal coalition numbered c. 250,000 people, one might asume c. 150,000 were women and children leaving c. 100,000 warriors.

- Livy Ep. 68

- Strauss, Barry (2009). The Spartacus War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 21–22. ISBN 1-4165-3205-6.

marius german.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 40; Theodore Mommsen, A History of Rome, IV.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 41.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 42.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp. 42-43.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp. 45-51.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 58.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp 57-58.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp. 61-62.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 125-130; Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 62

- Frontinus, Stratagems, 4.7.5.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp. 131-132; Plutarch, Marius, 18.1-2.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp. 132-133; Plutarch, Marius, 19.1-5.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 133-134; Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 62; Plutarch, Marius, 19.3-6; Orosius, Against the Pagans, 5.16; Florus, Epitome of Roman History, 1.38.9.

- Plutarch mentions (Plutarch, Marius, 10.5-6) that during the battle, the Ambrones began to shout "Ambrones!" as their battle-cry; the Ligurian troops fighting for the Romans, on hearing this cry, found that it was identical to an ancient name in their country which the Ligurians often used when speaking of their descent ("οὕτως κατὰ ὀνομάζουσι Λίγυες"), so they returned the shout, "Ambrones!".

- Frontinus, Stratagems, 2.9.1.

- Plutarch, Marius, 20.3.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 136-137.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 136-137; Plutarch, Marius, 20.4-6.

- Frontinus, Stratagems, 2.4.6.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 139-140; Plutarch, Marius, 21.1-2; Orosius, Against the Pagans, 5.16; Florus, Epitome of Roman History, 1.38.10.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 63.

- Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 64.

- Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, p. 140; Plutarch, Marius, 21.3.