Barbiton

The barbiton, or barbitos (Gr: βάρβιτον or βάρβιτος; Lat. barbitus), is an ancient stringed instrument known from Greek and Roman classics related to the lyre. The barbat or barbud, also sometimes called barbiton, is an unrelated lute-like instrument derived from Persia.

The Greek instrument was a bass version of the kithara, and belonged in the zither family, but in medieval times, the same name was used to refer to a different instrument that was a variety of lute.

Ancient descriptions

Theocritus (xvi. 45), the Sicilian poet, calls the barbitos an instrument of many strings, i.e. more than seven, which was by the Hellenes considered to be a perfect number, and matched the number of strings customary in the kithara.[1]

Anacreon[2] (a native of Teos in Asia Minor) sings that his barbitos "only gives out erotic tones".[1] (A remark which could have been metaphorical, or could have been literal and referred to tuning in the Greek Phrygian mode – roughly C Major.)[3]

Pollux (Onomasticon iv. chap. 8, § 59) calls the instrument barbiton or barymite (from βάρυς, heavy and μίτος, a string), an instrument producing very deep sounds which comes out of the soundbox. The strings were twice as long as those of the pectis and sounded an octave lower.[1]

Pindar (in Athen. xiv. p. 635), in the same line wherein he attributes the introduction of the instrument into Greece to Terpander, tells us one could magadize, i.e. play in two parts at an interval of an octave on the two instruments.[1]

Although in use in Asia Minor, Italy, Sicily, and Greece, it is evident that the barbiton never won for itself a place in the affections of ancient Greeks; it was regarded as a barbarian instrument affected by those only whose tastes in matters of art were unorthodox. It had fallen into disuse in the days of Aristotle, but reappeared under the Romans.[4][5] Aristotle said that this string instrument was not for educational purposes but for pleasure only.

Often Sappho is also depicted playing the barbitos, which has longer strings and a lower pitch. It is closely associated with the poet Alcaeus and the island of Lesbos, the birthplace of Sappho, where it is called a barmos.[6] The music from this instrument was said to be the lyre for drinking parties and is considered an invention of Terpander. The word barbiton was frequently used for the kithara or lyre.[3]

Modern interpretation

Barbitos

In spite of the few meagre shreds of authentic information extant concerning this somewhat elusive instrument, it is possible nevertheless to identify the barbiton as it was known among the Greeks and Romans. From the Greek writers we know that it was a deep toned instrument, with pitch range of at least two octaves, that had enough features in common with the lyra and kithara, to warrant their classification as a family of related instruments.[1]

Barbat

The later, unrelated instrument, is described by the Persians and Arabs as a kind of rebab or lute, or a chelys-lyre,[7] It was first introduced into Europe through Asia Minor by way of Greece, and centuries later into Spain by the Moors, amongst whom it was in the 14th century known as al-barbet.[8]

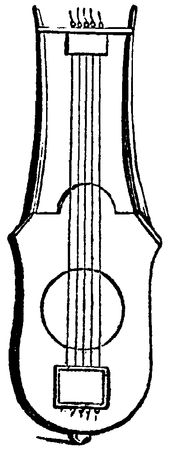

Third, unnamed, mixed lyre / rebab

Musicologist Kathleen Schlesinger identified a stringed instrument of unknown name that combines the characteristics of both lyre and rebab; It is represented in least four different ancient sculptures:[9] She writes:

It has the vaulted back and gradual narrowing to form a neck which are typical of the rebab and the stringing of the lyre. In outline it resembles a large lute with a wide neck, and the seven strings of the lyre of the best period, or sometimes nine, following the “decadent lyre”. Most authors in reproducing these sculptures showing it represent the instrument as boat-shaped and without a neck, as, for instance, Carl Engel. This is because the part of the instrument where neck joins body is in deep shadow, so that the correct outline can hardly be distinguished, being almost hidden by hand on one side and drapery on the other.[1]

The Barbat

The barbat (also called “barbiton”) is unlike the instrument depicted on Greek vase paintings. The Greek barbiton, however, although it underwent many changes, retained until the end the characteristics of the instruments of the Greek kithara whose strings were strummed and plucked, whereas the rebab was sounded by means of the bow at the time of its introduction into Europe.[1] At some period not yet determined, which we can but conjecture, the barbat approximated to the form of the large lute. An instrument called barbiton was known in the early part of the 16th century[10] and during the 17th century. It was a kind of theorbo or bass-lute, but with one neck only, bent back at right angles to form the head. Robert Fludd[11] gives a detailed description of it with an illustration:

Inter quas instrumenta non nulla barbito simillima effinxerunt cujus modi sunt illa quae vulgo appellantur theorba, quae sonos graviores reddunt chordasque nervosas habent.[1]

The people called it theorbo, but the scholar having identified it with the instrument of classic Greece and Rome called it barbiton. The barbiton had nine pairs of gut strings, each pair being in unison. Dictionaries of the 18th century support Fludd's use of the name "barbiton". G. B. Doni[12] mentions the barbiton, defining it in his index as Barbitos seu major chelys italice tiorba, and deriving it from lyre and cithara in common with testudines, tiorbas and all tortoiseshell instruments. Claude Perrault,[13] writing in the 18th century, states that "les modernes appellent notre luth barbiton" (the moderns call our lute barbiton). Constantijn Huygens[14] declares that he learnt to play the barbiton in a few weeks, but took two years to learn the cittern.[1]

The barbat was a variety of rebab, a bass instrument, differing only in size and number of strings. This is quite in accordance with what we know of the nomenclature of musical instruments among Persians and Arabs, with whom a slight deviation in the construction of an instrument called for a new name.[15] The word barbud applied to the barbiton is said to be derived[16] from a famous musician living at the time of Chosroes II (590-628 CE), who excelled in playing upon the instrument. From a later translation of part of the same author into German[17] we obtain the following reference to Persian musical instruments: "Die Sänger stehen bei seinem Gastmahl; in ihrer Hand Barbiton(i) und Leyer(ii) und Laute(iii) und Flöte(iv) und Deff (Handpauke)". Mr. Ellis, of the Oriental Department of the British Museum, has kindly supplied the original Persian names translated above, i.e. (i) barbut, (ii) chang, (iii) rubāb, (iv) nei. The barbut and rubab thus were different instruments as late as the 19th century in Persia. There were but slight differences if any between the archetypes of the pear-shaped rebab and of the lute before the application of the bow to the former – both had vaulted backs, body and neck in one, and gut strings plucked by the fingers.[1]

Modern reconstruction

The barbitos is part of the Lost Sounds Orchestra,[18] alongside other ancient instruments which Ancient Instruments Sound/Timbre Reconstruction Application (ASTRA) have recreated the sounds of, including the epigonion, the salpinx, the aulos, and the syrinx.

The sounds of the barbitos are being digitally recreated by the ASTRA project, which uses Physical modeling synthesis to simulate the barbitos sounds.[19] Due to the complexity of this process the ASTRA project uses grid computing,[20] to model sounds on hundreds of computers throughout Europe simultaneously.

References

- Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 387–388.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Bergk (1882) Poetae Lyrici Graeci, 4th ed., p. 291, fr. 143 [113]; and p. 311, 23 [1], 3; and 14 [9], 34, p. 306

- West, Martin L. (1992). Ancient Greek Music. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814975-1.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Susemihl-Hicks (1894) Aristotle, Politics, viii. (v.), 6th ed., pp. 604 (=1341a 40) and 632; Daremberg and Saglio, Dict. d'ant. gr. et rom.

- See Schlesinger (1911)[1] article "Lyre", p 1450, for more references to the classical authors.

- Anderson, W.D. (1994). Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3083-6.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Johnson's Persian-Arabic-English dictionary: barbat, a harp or lute, barbatzan, player upon lute, pl.barabit; G. W. Freytag, Lexicon Arabico-Latinum, i. p. 103; barbal (Persian and Arabic), batbitus, genus testudinis, plerumque sex septamve chordis instructum (rotundam habet formam in Africa); Lexicon Aegidii Forcellini (Prato, 1858); Martianus Capella (i. 36) "Barbito aurataque chely ac doctis fidibus personare"; G.B. Doni, Lyra Barberina, ii. index

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Enumeration of Arab Musical Instruments, xiv. c.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: (a) See C. Clarac, Musée du Louvre, vol. i. pl. 202, no. 261. (b) Accompanying illustration. [See also Kathleen Schlesinger, "Orchestral Instruments", part ii., "Precursors of the Violin Family," fig. 108 and p. 23, pp. 106–107, fig. 144 and appendix.] (c) Sarcophagus in the cathedral of Girgenti in Sicily, illustrated by Carl Engel, Early History of the Violon Family, p. 112. A cast of preserved in the sepulchral basement at the British Museum. Domenico (Palermo, 1834) Lo Faso Pietra-Santa, le antichrita della Sicilia, vol. 3, pl. 45 (2), text p. 89. (d) C. Zoega (Giessen, 1812) Antike Basreliefe von Rom, atlas, pl. 98, sarcophagus representing a scene in the story of Hippolytus and Phaedra.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Jacob Locher (Basil, 1506) Navis Stultifera, titulus 7, illustration of a small harp and lute with the legend nec cytharum tangit nec barbiton.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Robert Fludd (Oppenheim, 1617) Historia Utriusque Cosmi, tom. i. tract ii. part ii. lib. iv. cap. i. p. 226.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Lyra Barberina, vol. ii. index, and also vol. i. p. 29.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Claude Perrault (Amsterdam, 1727) "La musique des anciens", Oeuvres complètes, tom. i. p. 306.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Constantijn Huygens (Haarlem, 1817) De Vita propria sermonum inter liberos libri duo. See also Edmund van der Straeten, La Musique aux Pays-Bas, vol. ii. p. 349.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: See (Lucknow, 1822) The Seven Seas, a dictionary and grammar of the Persian language, by Ghazi ud-din Haidar, king of Oudh, in seven parts (only the very long title of the book is in English). A review of this book in German with copious quotations by von Hammer-Purgstall (Vienna, 1826) Jahrbucher der Literatur, Bd. 35 and 36; names of musical instruments, Bd. 36, p. 292 et seq. See also R.G. Kiesewetter (Leipzig, 1843) Die Musik der Araber, nach Originalquellen dargestellt, p. 91, classification of instruments.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: The Seven Seas, part i. p. 153; Jahrb. d. Literatur, Bd. 36, p. 294.

- Schlesinger (1911)[1] cites: Fr. Ruckert (Gotha, 1874) Grammatik, Poetik und Rhetorik der Perser, nach dem 7ten Bde. des Hefts Kolzum, p. 80.

- "Lost Sounds Orchestra". Archived from the original on 2009-09-02. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- "ASTRA". Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- "grid computing". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barbitos. |